Where's the digital?: The State of Cultural Nonprofits in Philadelphia

This week the @phillyhistory team is taking a break from #explore1918 to talk about the present state of the cultural sector in Philadelphia. With inspiration from our assigned readings by the Technical Development Corporation, my colleagues @tmaust, @engledd, @dduquette, and @yingchen have already contributed to this series with some great specific examples and ideas. I’m going to take a broader approach, however, and address some of my reactions to the readings.

What’s broken in the cultural sector?

1. Lack of organized goals/realistic conversations at the top

The two writeups have key point in common: cultural non-profit professionals are not having the right conversations. It can be scary to admit when an organization is not doing well, but this acknowledgement is the first step to fixing the problem. Boards and funders especially don’t want to prioritize “saving” a struggling organization. A fundraiser to renovate a roof isn’t as sexy as a fundraiser for an exciting new show, even if the former is more important.

This is a Facebook status that my friend who works at a homeless shelter recently posted. Whether it's money or labor, people often have a very specific idea of how they want to donate, even if it doesn't coincide with what the organization needs the most.

Before getting to the point of needing to have these conversations, TDC found that many organizations don’t have clearly defined goals and priorities. At the same organization, different employees, funders, and board members may have different goals. These competing interests within an organization obviously causes issues.

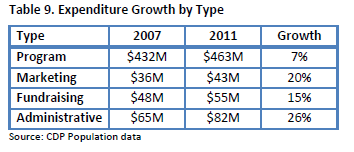

A societal emphasis on growth, which is not always the best goal for an organization, often fuels these competing interests or unwillingness to acknowledge problems. As the TDC explained, an organization can exhibit growth in the short-run while hurting itself in the long-run. For some smaller organizations, working with what it has is a better goal than expansion.

In my opinion, a potential (partial) solution for each of these problems is cultural professionals who are better trained in nonprofit management, whether that's through graduate school or workplace training. I’m so fortunate that I’m getting to take Nonprofit Management as part of my graduate program, and I hope that similar graduate programs require it, too. When I enter the cultural nonprofit job market, I will bring this knowledge with me.

Of course, better training is not a complete solution. No amount of training can prepare professionals for the many variables that come with actually working at a nonprofit. No amount of training can eliminate donors and board members who maintain priorities that are out of sync with the cultural sector laborers. The very idea of training has financial barriers. Yet, better training is the main thing that I can think of as an important step for knowing how to set priorities well and further how to gracefully discuss when said priorities are not met. What am I missing?

2. Where’s the digital?

Neither of the readings discussed the studied institutions’ digital presence. There was some discussion of generational issues within the cultural sector in terms of professionals wanting to stick to the status quo when that may not be the best option. The TDC specifically cited an old-school bent in marketing practices. Apparently, many cultural sector non-profits still emphasize short-term print marketing initiatives and don’t track response analytics. Though the TDC did not mention it, it seems to me like the solution to this issue is the internet.

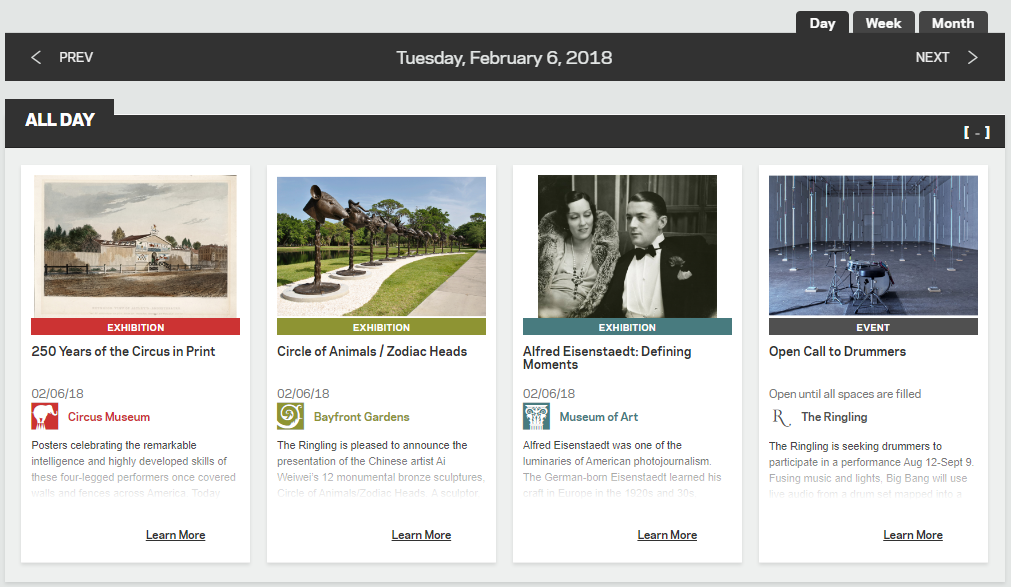

The Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota, FL maintains a web calendar that keeps visitors updated about events and exhibitions while promoting pieces from the permanent collection.

Creating an attractive website is a great way to reach wider audiences. Further, while maintaining a web presence comes with some overhead costs, it is certainly cheaper than the building maintenance frequently cited in the TDC reports as an issue.

While small institutions have problems with maintaining a website after contracting with a third-party for its creation, it's my hope that a new generation of cultural sector professionals will have the webdesign skills necessary to reduce this issue.

Web marketing is also fantastic because it makes tracking analytics easier. While an institution may be unable to note the amount and demographics of those viewing a print ad, such data is more readily available for web marketing.

In fact, the #explore1918 initiative is a testament to the power of the digital to promote and fund nonprofit historical ventures.

I've barely scratched the surface of the TDC reports. If I had more space, I would have addressed the idea of establishing a community need for a cultural institution before creating one, or when deciding to discontinue one. I hope to explore this topic in a later post.

For now, my main question is, how can cultural nonprofits use the digital landscape to meet their goals?

Or maybe I'm getting too ahead of myself?

Yes! You are on target.

I remember a discussion back in 1999 with the head of a (nameless) history museum about leveraging the web for their mission. The response was: "No, we'll wait until the dust settles." Looking back, I remember a sense of confusion and a lot of competition. Like, "No, sorry. If people want history, they'll have to come into our actual space to get it."

please vote have me my sister no people votes i beg the same sister