Principles of Communism by Frederick Engels - Review and Analysis

Proletarian revolution is the only solution to the contradictions inherent to a capital system. Only by eliminating the property system and wage labor can the proletariat be freed from the oppression of the bourgeois. Engels’ Principles of Communism lays the foundation for understanding the need for and inevitability of the rise of communism.

Why Engels?

I recently read Frederick Engels’ The Principles of Communism for the first time after meaning to for a long time. In it Engels outlines the basic principles and assertions of communism as a political philosophy and the economic underpinnings that make communism a necessary movement. Engels founded Marxist theory with Karl Marx and provided for Marx during Marx’s early publication years. Additionally, Engels consolidated and organized some of Marx’s works which otherwise most likely would have gone unpublished for many years. The communist movement and Marxist analysis as a whole have Engels to thank for some of their most fundamental work.

Image from the Encyclopedia Britannica

Is the Proletariat Still Relevant?

In Principles of Communism, Engels provides the foundational class analysis of the material conditions of the proletariat and their existence as a symptom of the industrial revolution in a system which was set up to create and perpetuate the existence of private property. When we consider how our world has developed since the first industrial revolution it can seem easy to dismiss Engels’ analysis as no longer relevant. We might ask: “If the contradictions in capitalism lend themselves towards its own destruction, then how can the system of private property have lasted up until now?” We might even go so far as to argue that those contradictions have been addressed and that the continuation of technological growth has lended itself to the elimination of the proletariat, since we do not now see a world populated by factory workers. Though superficially, there may be some truth in these statements, the material conditions of the factory workers in Engels’ time are identical to those of the proletariat in the modern age. If we define the proletariat the same way as Engels did, namely: “that class in society which lives entirely from the sale of its labor and does not draw profit from any kind of capital; whose weal and woe, whose life and death, whose sole existence depends on the demand for labor,” it is clear that the worker class still exists under the same conditions today. The proletarians of the 21st century are all those workers who today provide the labor that makes global capitalism run: drivers, cooks, service staff, retail staff, office workers. The proletariat of today bear the same relation to capital, private property, and the wage system that their comrades of the 19th century died under. These workers provide all the labor-power that fuels the capitalist system of production, but bear none of the so-called benefits of its productive capacity.

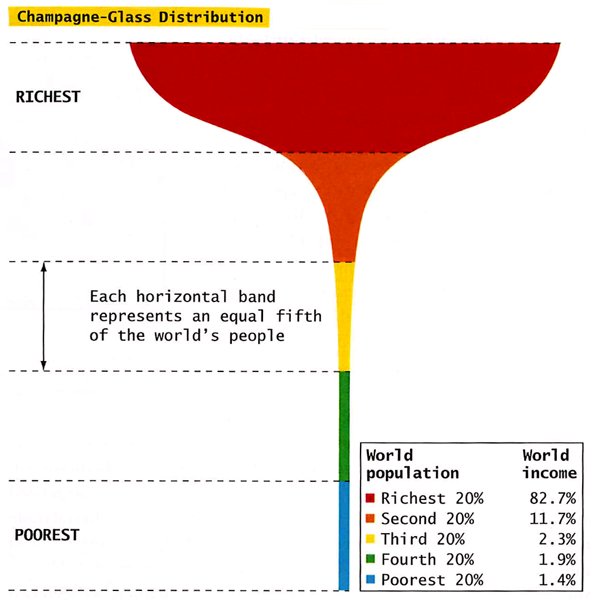

Image from GreenPeace GreenWire USA

What’s Wrong with Wage Labor

While it is clear the workers’ revolution has a ways to go, it may not be immediately apparent why the capital system is so harmful to the proletariat. Engels analyses the conditions of the labor market simply: “Labor is a commodity, like any other, and its price is therefore determined by exactly the same laws that apply to other commodities. In a regime of big industry or of free competition – as we shall see, the two come to the same thing – the price of a commodity is, on the average, always equal to its cost of production. Hence, the price of labor is also equal to the cost of production of labor.” This is all well and good but the capitalist in attempting to derive all available profit from their relationship to labor and production are not just incentivized, but even required, by the competitive marketplace, to lower the cost of labor to the minimum wage upon which it is capable to sustain life. The contradiction of capitalism is that within its foundation lie the seeds to its own destruction. As Engels points out: “the proletariat develops in step with the bourgeoisie. In proportion, as the bourgeoisie grows in wealth, the proletariat grows in numbers. For, since the proletarians can be employed only by capital, and since capital extends only through employing labor, it follows that the growth of the proletariat proceeds at precisely the same pace as the growth of capital.” As the bourgeois gain more capital, they create more of the workers who will lead the revolution to annihilate the class hierarchy. If anything the progression of social and economic relations since Engels’ time have shown this part of his analysis to be even more true than his words suggest, the system of capital necessitates a capitalist class that will only continue to concentrate wealth in fewer and fewer hands, and this concentration in turn creates the conditions which make the communist movement the necessary path forward for all workers.

Image from The Society Pages Graphic Sociology

The Boom and Bust Cycle and its Effects

Engel’s economic analysis of the system of capital continues with his description of the boom and bust cycles inherent to capitalism, and their existence as a requirement within the capitalist mode of production. Capitalism as a system rewards an endlessly expanding production capacity. In this topsy-turvy incentive system, often more is produced than is needed.1,2 When these finished commodities are unable to be sold a commercial “so-called crisis” breaks out, and factories close. When factories close, their owners go bankrupt, and the workers go without bread Eventually these overproduced goods will be sold off and gradually business replenishes itself. However, soon enough the same overproduction happens and the bust cycle repeats itself. Engels argues that the boom and bust cycle inevitable in a capitalist system results in the following:

- Big Industry that outgrows free competition

- Big Industry now must shatter the individual production model

- The survival of Big Industry will require this seven year boom-bust cycle and the devastation it brings to the general civilization which plunges the proletariat as well as large sections of the bourgeoisie into misery

The only way to combat this boom-bust cycle is to upend the system of capital and promote a worker-controlled system. The only way to end the system of capital, Engels continues, will be to abolish private property and to live in a system where all property would be described as held communally, by all those who require its utilization, and not just those capitalists who previously sought to profit from exclusionary ownership over the same.

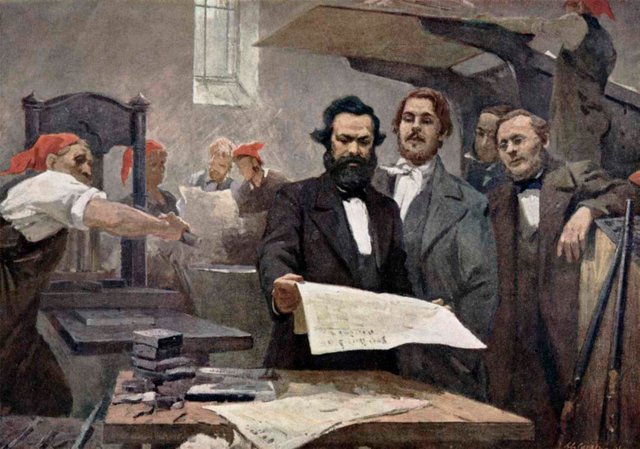

Image from the International Institute of Social History

Principles of Communism is a comprehensive and easy to read introductory work into the foundations of communism. Engels goes beyond just laying the desires of the political ideology by explaining the material conditions that provide the class analysis necessary to arrive at communism as the final production form. By providing the reader with all the necessary background and foundation to understand communism, Engels has created a remarkably strong argument in this shrewd work. I had put off reading Engels for quite some time, and now I wonder why I ever waited so long. Engels has put so eloquently what I often spent many more pages trying to understand from the works of others.

Footnotes

A capitalist ‘free market’ system rewards those firms that control goods at the time that they are desired. It is from this that liberals and other supporters of capitalism derive the argument that the bourgeoisie provide the necessary function of taking on risk in a capital system, a risk that they argue the worker would never desire to take or be able to afford taking. While it is clear this argument requires a perpetually impoverished proletariat just barely escaping starvation, Putting its problematic premises, Engels points out that there is reason within their argument: each boom and bust yields the annihilation of wealth for large portions of bourgeoisie. Their argument ignores, of course, the fact that it is workers who truly lose everything. When the bourgeoisie go bankrupt, what choice is there for the proletariat, who is living in a state of perpetual bankruptcy and near ruin? The worker must instead go without bread, that is at least until they are able to find another capitalist willing to exploit their alienation from property. Because firms which have goods to sell at the time they are demanded receive the benefits of a capital system, the competitive market drives all firms to strive to be this firm. Each firm must compete to increase their production model to an unsustainable level which will always leave some firm (and often times most firms) bankrupt when they are eventually unable to time to decline of demand for the goods they are striving to overproduce. It is this that a Marxist refers to as the ‘contradictions in capital.’ These are the material conditions inherent to a capital system that can only be remedied by an end to the property system and the rise of a truly free proletariat.

Advances in our increasingly automated financial markets further exacerbate the overproduction model. As the money market pushes investment capital into those firms that are expected to produce the most (because it is impossible to predict the future crash, which while clearly inevitable, would not exist if it were predictable) these firms are further expected to produce an equally exorbitant return on investment. The crescendo of this financial fervor towards expected future rewards creates the perfect environment for the coming crash. While these trends spell doom for the bourgeoisie who invest in these firms and the proletariat who sell their labor to these firms, as classes the gap between wealth held by the proletariat and the bourgeois become further and further separated. The promise of future rewards drives each firm to increase the profitability of their production model, something that can only be done by lowering the wage paid to the proletarians employed by that firm, absent changes in technology or the price of raw goods which will quite quickly equalize in a global market. As all firms race to lower the wage paid to their chunk of the proletariat and further engorge the capitalists who have chosen to bet their investment capital in them, the conditions of the proletariat become identical to that of the slave and the prisoner.

You can read Engels' Principles of Communism here: Principles of Communism on Marxists.org