How to Write for Another’s Comedic Voice

So, in an earlier post I wrote about how I write in a show called Minnesota Tonight. In the post I talked about (wrote about?) the comedic writing process as it relates to gender and identity and why I’m glad I write with women because of it. But now, I would like to talk (let’s stick to ‘talk’ as this is my 1st person voice in your head) about comedic voice as a part of the writing process.

First things first… What the hell is comedic voice?

Comedic voice is a strange amalgam of perspective, privilege, identity/brand, method, cadence, and weird set of other things that make a comic capable of telling a joke well. Its the reason why so many comedians have certain styles of jokes and why not all styles can be imitated by other comics.

It takes a really long time for comedians to find their own comedic voices (I haven’t pinned down mine completely yet) and it takes a bit longer to figure out someone else’s; which is my current situation in Minnesota Tonight.

If you’ve never seen Minnesota Tonight, which is a shame because it’s a great show, then you should know that it is a Minnesota based comedy show, in the same vain as Last Week Tonight and The Daily Show just not as good. In the show there are a variety of comedic segments, and the segment I write for is called MN10. MN10 is a 10 minute monologue identifying a problem in Minnesota with jokes sprinkled in to make the segment fun, yet surprisingly informative.

Here’s a video if you’re interested:

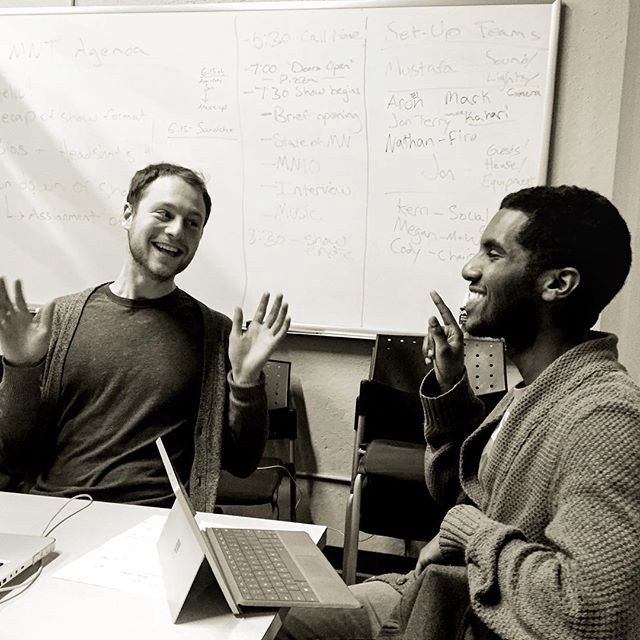

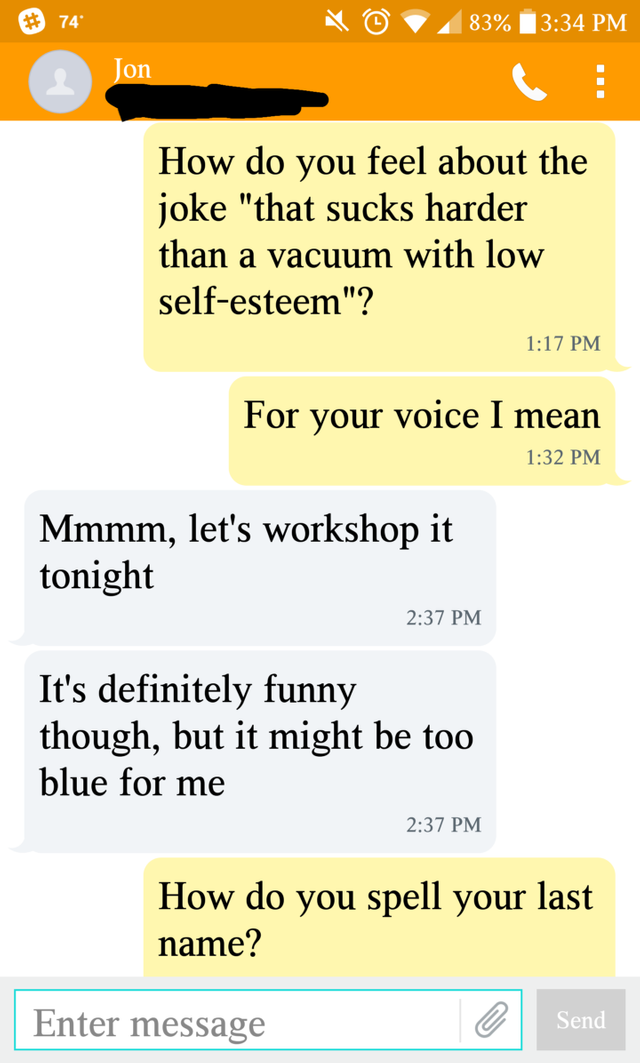

See that bearded guy up there? That’s Jonathan Gershberg (it might be Gurshberg or Girshberg, I can’t be bothered to check; first name’s definitely Jonathan though). Jonathan reads everything he says off of a script that I and group of writers write. Now, other than research, argument structure, and joke writing, the hardest part of the writing process is writing in Jon’s comedic voice. Why? Because Jon can’t say every joke our team writes and that sucks harder than a vacuum with low self esteem.

See that joke right there? The “that sucks harder than a vacuum with low self-esteem.” joke is something I’m comfortable writing. I enjoy the humor in that joke. Writing jokes like that are instinctive for me, because of that they can be spoken in my comedic voice. That’s a perk of writing your own stuff, everything you write will fit your comedic voice. However, it’s also the problem with writing for other people; especially Jonathan Gershberg.

Personally my comedic voice is dark, mean, immature, and does well with death, mayhem, racial inequality, non sequiturs, and birds (with feathers).

Jon’s comedic voice is… not all that.

Because of this sometimes Jon and I will clash on whether or not certain jokes should be in the monologue or not. More often than not, Jon will be right. He knows if he can make something funny and has a very good idea of what he can and can’t say. However, if I ever disagree with Jon on a joke that I think is important the two of us work hard to find a middle ground so the both of us have something to work with.

As mundane as it sounds, collaboration like this is essential for comedy writing. It’s the only way I can actually feel like I’m contributing without being discouraged by Jon. And the only way Jon can ensure everything I write fits his voice. However it took me and Jon a while to figure this out.

Jon and I have been writing MN10 for over a year now and have a pretty good grasp on how he will tell a joke and whether or not he’ll be comfortable with a joke like this. Simply put we have a rapport. Our relationship is built on time and with that comes the patience to argue for or against jokes.

And honestly this time was the best way to learn to write in Jon’s voice, because for over a year Jon and I have frequently fought over the kind of jokes he can tell.

When the two of us first met our writing relationship was cut and dry. I would propose a joke and then if he liked it we would use it, if not he nixed it. For a while it would sound like this:

Aron: How about this (joke about a dead person or something)?

Jon: I don’t think I could say that.

Aron: Oh, okay (simmering with rage).

Then it evolved into:

Aron: How about this (joke about a sexual act)?

Jon: Yeah, that’s not right for the show.

Aron: What isn’t right for the show, Jon, comedy?

Mike: I think the joke is funny. (Mike is Jon’s roommate. He’s not a writer.)

Aron: Shut up, Mike! (I didn’t mean that. Mike was just collateral damage.)

And now it’s become:

Aron: How about this joke?

Jon: I’m not sure.

Aron: …Could we discuss it, later.

Jon: Alright.

And most of the time when we do discuss it we end up work shopping it to fit his voice and keep my original joke. At this point it’s become weirdly natural for us to debate the merit of a joke.

What’s great about Jon is that if he doesn’t want to say something or can’t agree with a joke he won’t usually blow it off. He’ll often ask us (the writers)to adapt it for him. Write it in a way where we he can feel comfortable with the content, but keep the humor.

Sometimes that means I’ll have to deescalate a joke, make it less insane or edgy to fit his voice. Take a look at a line where Jon and I had to deescalate to make it work.

That’s right I’m talking about Teddy Bridgewater, he is the I-35W of Vikings’ Quarterbacks. He can’t make a pass, he’s terrible under pressure, and 13 people are dead.

If you’re laughing then we’re kindred spirits. If you’re not then you’ll be happy to see the changes Jon asked I make.

That’s right I’m talking about Teddy Bridgewater, he is the I-35W of Vikings’ Quarterbacks. He can’t make a pass, he’s terrible under pressure, and he has a history of letting people down.

That’s a lot more tolerable, right? It’s essentially the same joke, but with one change it can be spoken in Jon’s voice.

So at this point of the post you’ve probably come to the summation that writing in another person’s voice is really just having a conversation with them in regards to joke writing. Which yeah, it is, but this gets one step harder when you have more than two writers in a room.

For almost half a year there has been more than two writers writing MN10. Which means the conversations on how to fit jokes to Jon’s voice can get a bit dicey.

Our team has five different writers including Jon and I. Our three other writers (great peps by the way) have drastically different comedic voices. One is malevolently sarcastic with sincere undertones, another is lofty and ever so slightly rye, and the the third is witty and has a love of debauchery. All of us have to write together and when we do we’ll often argue on how a joke should be written, presented, or even spoken, before we even consider if Jon’s voice will fit the joke.

With so much going on in the writer’s room we can’t really discuss and modify every good or bad joke we write to fit Jon’s voice; it would take to long. So we do two things in order to make sure Jon can comfortably say the things we write: Punch-ups and Failure.

Punch-ups are a comedy standard. Its essentially the act of taking your script to other writers and having them attack it with better humor. This is done with television shows, movies, even certain novels. Like I said earlier MN10 is one of many segments for Minnesota Tonight. So every Saturday before a show, we’ll have writers for other segments get together to determine if the stuff we wrote was funny or not. We’ll give them multiple interpretations of a joke, questions on how to make something funny, and 90% of the time they’ll punch it up in a direction that Jon can be comfortably with. They’ll also validate the humor in our writing, but that’s a whole other thing.

Failure is failure. Its not really a metaphor for anything. Sometimes as a unit we’ll writing something that will slip through punch-ups outside of Jon’s voice. When this happens we get a front row seat of seeing Jon perform a joke he is uncomfortable with and fail. It’s not super fun, but it does sober us to the limitations Jon’s voice has. Despite the power of certain jokes, if Jon can’t adequately perform them, then they’re better off gone.

All in all, writing in someone else’s voice takes time, trust, a willingness to experiment, and the sense to know when to stop. It’s one of the biggest hurdles writers have to deal with when writing for others, and because of that it is one of the most important to learn.

If you’re interested in watching or even writing for Minnesota Tonight you can go to our Facebook page. Come out to our Election show this November 8th at .The Brave New Workshop Comedy Theatre. We’ll have live results from the Minnesota Tonight team, improv from Mayhem improv, music from General B and the Wiz, and lots and lots of booze. Get your tickets now!