Repost: “Three Ravens” — recreating an early music performance pt 1

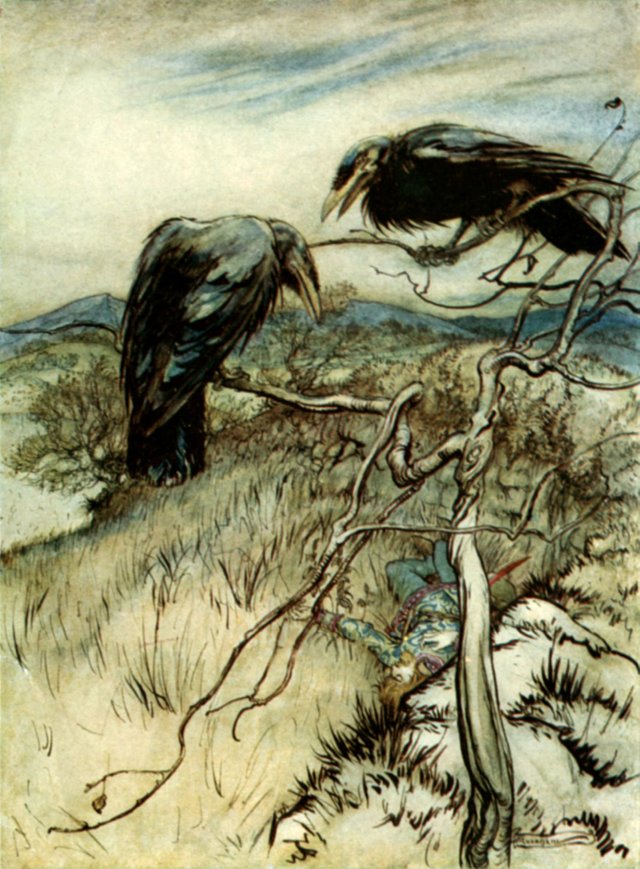

(“The Twa Corbies” by Arthur Rackham for Some British Ballads)

This is a repost of one of my research papers from my old website, that was one of the first posts I made on Steemit. Now that I have a bigger audience, I’d like to share it again.

Introduction: Beauty Found Within Life and Death

Music is the language of our heart and soul when words fail, and can evoke powerful images and atmospheres with mere sound.

I first came upon "The Three Ravens" when I was looking for more period pieces to add to my repertoire for nights around the campfire. The imagery of the words and the poignant beauty of the story (with just a touch of the macabre) grabbed me by the lapels and shook me: I immediately found myself on that field, in the fog, listening to the birds and seeing what the composer saw.

The reality -- and frequency -- of death in the Renaissance is something we modern souls prefer to gloss over, but the truth is, death is something my living history/historical performance persona, Emma, would likely not have been a stranger to. There are several accounts of plague throughout English history, both before, during, and after the reign of the Tudors -- and that doesn't take into account the deaths from foul play (depends on which account you read!), deaths from accidents, or deaths from general sickness.

Art (whether music, poetry, painting, etc.) is unique in that it has a tendency to become the outlet and the vehicle by which we come to grips with the hard parts of our lives. "Three Ravens" is no exception.

The Three Ravens

“The Three Ravens” is an anonymous English tune predating Thomas Ravenscroft’s Melismata collection of 1611 in which it was first published. It is sung from the point of view of a group of ravens debating what to eat, and details the events surrounding a dead knight in a meadow. The birds note the fact that the man’s hawks and hounds never leave his side, and observe the arrival of a pregnant woman – the “fallow doe” – who is presumably the knight’s wife, mistress, or lover, who then buries him (thus removing the birds’ chance at a meal) and dies herself at his side. The last verse of the song takes an omniscient point of view, stating that “every gentleman” (i.e. every good, honorable man) will find himself with loyal companions such as the slain knight’s hawks and hounds, and the unfailing love of a woman (footnote 1).

There is some debate on dating "Three Ravens," given that it was published so late in period by Ravenscroft. However, after considering the research, I believe it is a fairly safe bet that the song is older than 1600. According to Reese (834), Ravenscroft was known for collecting popular songs from the populace and printing them. In Ravenscroft's preface to his collection, Pammelia, he writes:

"...what seems old, is at least renewed, Art having reformed what pleasing tunes injurious time and ignorance had deformed." (Reese 834)

Reese suggests that this statement coupled with the texts found in Ravenscroft's "catch" (song) books that have been mentioned in earlier sources indicate he was an avid "recycler" of old tunes. It is also noted that at the latter part of the 16th century, laws were in effect to ban the tradesmen from singing new, popular music -- an effort to protect the court musicians and professional actors of the time. Therefore, Ravenscroft may not have even been able to collect the song for several years after its writing, and given the publication date of Melismata, that effectively pushes the tune prior to 1611, if not earlier.

C.A. Powers has also done research into "Three Ravens," and purportedly, it is the same tune as “King Edgar Deprived” (a ballad cataloged by Thomas Deloney between 1592-1593 detailing King Edgar’s losing of a potential lover to a knight of his court), which also throws the date of the song prior to 1600.

The Madrigal... and Women in Music

The madrigal began in the early 16th century as a form of poetry set to music popular with the aristocracy in the Italian courts (Machlis & Forney 109). Typically, madrigals were written for multiple voices, either a cappella vocals, or vocal and instrumental combinations. The form relied heavily on a device called "word painting," (113) or the use of mimicking the action of the lyric in the melodic line (for example, in John Farmer's "Fair Phyllis," he makes the melodic line fall as the singers sing "up and down") (2).

Eventually, the Italian madrigal migrated to England, and the English took it and made it their own. The art form flourished during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, and lasted through the reign of her successor, James I, at which point we see more virtuosic performance with heavy ornamentation, melismatic (3) passages, and vivid emotional description (110-111).

The study of music at this time was also considered to be a critical part of a young woman's education (especially if her family was well off), and we begin to see women performing music in a professional capacity as well as at home (Machlis & Forney 108). For example, Francesca Caccini (b. 1587) became one of the highest paid musicians in the Medici court (Brown 267). And the Concerto Della Donne -- an all-female professional singing group formed in 1580 by Duke Ferrara -- won acclaim throughout Italy and several other European courts (Brown 269) (4).

——————-

1 “leman” archaic: sweetheart or lover, especially mistress. From Middle English lefman, leman, from lef lief. First Known Use: 13th century. Page 664.

2 Farmer, John. "Fair Phyllis," The Norton Recordings: Sony 2003.

3 The act of singing multiple notes using one word or even one syllable.

4 Performing as a woman in Renaissance Europe was not without its difficulties. Prior to the mid 16th century, women's role in music was typically limited to the scope of the religious sector, or within a private home. (Brown 270). If she were to perform publicly, it raised uncomfortable questions about her morality. It wasn't until the latter part of the century that views became relaxed.

Resources

-Brown, Meg Lota and McBride, Kari Boyd, Eds. Women's Roles in the Renaissance. Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing, 2005.

-Cantaria Folk Song Archive. "The Three Ravens." http://chivalry.com/cantaria/lyrics/three-ravens.html. Accessed 4 January 2014.

-Child, Francis James. "Child 26: Three Ravens." http://www.springthyme.co.uk/ballads/balladtexts/26_ThreeRavens.html. Accessed 1 Oct 2013.

-Powers, Courtney Allen and ed. Van der Vliet, Charrie. "Chapter 13: The Three Ravens." 30 Elizabethan Songs – With Documentation. 2008. http://charric.110mb.com/magic/magicmusicfortheweb/13-threeravens.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2013.

“Leman.” Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. 10th ed. Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Inc., 2000.

-Lumina Vocal Ensemble. "Three Ravens by Thomas Ravenscroft." YouTube, 2013.

-Lute Society of London. "Beginners' Lessons." http://www.lutesociety.org/pages/beginners. Accessed 27 Dec 2013.

-Machlis, Joseph and Forney, Kristine, eds. “Renaissance Sacred Music” The Enjoyment of Music, Ninth. 9th ed. New York: Norton & Company, 2003.

-McGee, Timothy J. Medieval and Renaissance Music: A Performer's Guide. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1985.

-Ravenscroft, Thomas. "The Three Ravens." Melismata. 1611. Ed. Jurgen Knuth. IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library, 27 Oct 2011. http://imslp.org/wiki/The_Three_Ravens_(Ravenscroft,Thomas). Accessed 22 Sept 2013.

-Ravenscroft, Thomas. "The Three Ravens." Melismata. 1611. Ed. Jurgen Knuth. http://imslp.org/wiki/Melismata(Ravenscroft,_Thomas). Accessed 22 Sept 2013.

-Reese, Gustave. Music in the Renaissance. New York: Norton & Company, 1959.

-Taylor, Livingston. Stage Performance. New York: Pocket Books, 2000.

-Waldron, Jason. Progressive Classical Guitar Method: Book 1. South Australia: Koala Publications, 2000.

Resteemed, your post will appear in the next curation with a SBD share for you!

Your post has been supported and upvoted from the Classical Music community on Steemit as it appears to be of interest to our community.

If you enjoy our support of the #classical-music community, please consider a small upvote to help grow the support account!

You can find details about us below.

The classical music community at #classical-music and Discord.

Follow our community accounts @classical-music and @classical-radio.

Follow our curation trail (classical-radio) at SteemAuto or help us out with a delegation!

Thank you so much! I am glad it was of value! I’ll have the second part up next week. 🙂