Random Stuff You Didn't Know About Christian History

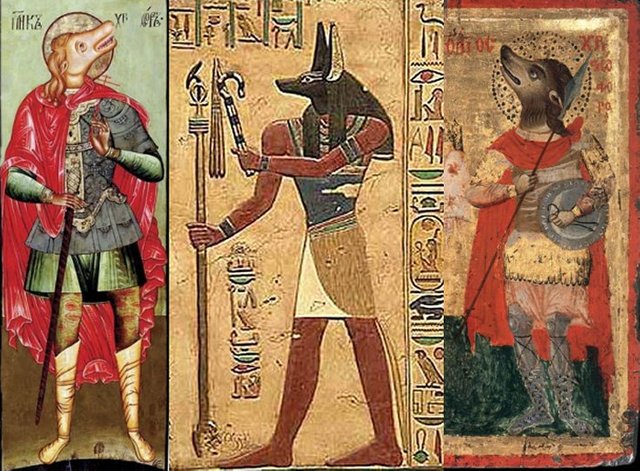

For centuries, Christians around the world venerated icons of a dog-headed man because of a typo/mistranslation of St. Christopher Cananeus (the Canaanite) as St. Christopher Canineus (the dog). Veneration of St. Christopher in the Roman Catholic Church ended in 1970, following the Vatican II reforms.

The oldest gospel narrative, the Gospel of Mark, gives neither an account of the virgin birth nor of the resurrection of Christ. It ends abruptly with the women going to visit the tomb and being turned away by a man who claims Christ is risen from the dead and gone from the tomb. The ending of Mark in English Bibles is a forgery that is not present in the original Greek. As a genuine historical account, Mark records the history from the point the disciples met Christ to the point that Christ departed, with nothing to say about the life of Christ before they met him or after his death. In later gospel narratives, the man at the tomb is recast as an angel and accounts of Jesus visiting the disciples in his resurrected body are added.

The early Church fathers claimed that the Gospel of Matthew was the oldest gospel, and that it had originally been written in Hebrew/Aramaic (the Church fathers considered Hebrew and Aramaic to be the same thing), which is almost certainly false. Most of the Gospel of Matthew is transliterated directly from the Greek of the Gospel of Mark, using the exact same words, which would be impossible if Matthew was a translation of a separate Hebrew original. And while the Church fathers do speak of a Hebrew gospel of Matthew, the content attributed by them to the gospels of the Hebrews is entirely different than the content of the Gospel of Matthew we have today. Furthermore, throughout the Gospel of Matthew, the author quotes the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament, basing his arguments on passages that don't even exist in the Hebrew, indicating that a Hebrew original of the Gospel of Mathew is quite impossible. For example, Matthew 1:23 cites Isaiah 7:14 as saying, "Behold, a virgin shall conceive...," following the Septuagint, when the Hebrew reading of "a woman shall conceive" wouldn't even fit the narrative Matthew is trying to paint. Or take Matthew 12:21 that cites the Greek version of Isaiah 42:4 as saying "And in his name will the Gentiles trust," while the Hebrew says, "And the isles shall wait for his law," a reading that would make no sense in the context of Matthew. Or take Matthew 4:10, where Satan tempts Jesus to worship him and Jesus cites Deuteronomy 6:13, following the Septuagint version, saying "Thou shalt worship the Lord thy God, and Him only shalt thou serve," where the Hebrew "Thou shalt fear the Lord they God, serve him, and shalt swear by his name" obviously lacks the same force and wouldn't have been such a witty comeback or retort. None of the New Testament has a Hebrew/Aramaic original; even the Gospel of Mark can easily be demonstrated to have been originally composed in Greek.

The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles claim to be letters written by Luke, the disciple of St. Paul, to a certain Theophilus. (Cf. Luke 1:3, Acts 1:1) Even if authentic, which they almost certainly are not, they cannot possibly be first-hand accounts, since Luke learned the gospel narrative through St. Paul, who only met Jesus long after the crucifixion. The Gospel of Luke is supposed to really be the Gospel according to St. Paul, a man who was not present at the time of any of the events recorded in the narrative, but is written down by Paul's disciple Luke. Both Luke and Acts are records of oral traditions. Furthermore, they are both almost certainly forgeries, since they conflict with Paul's own accounts.

The Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles were basically polemical essays in revisionist history. The Christianity of St. Paul conflicted with the Christianity of St. Peter. Paul taught a doctrine of justification by faith apart from the works of the Jewish law. (Cf. Romans 3-5) According to Paul's own account, this conflicted with the practice of James and Peter, who encouraged gentiles to undertake circumcision, convert to Judaism, and obey the Hebrew law in order to become Christian. St. Paul testifies that he had to "oppose [Peter] to his face," because of his conflicting interpretation of law and gospel. (Cf. Galatians 2) Paul claimed to have learned his gospel directly through divine revelation, therefore seeing himself as no less of an authority than Peter. The tradition of Peter and James rejected the justification by faith narrative of St. Paul, and emphasized righteousness by obedience to Judaic biblical law. (Cf. James 2) The Acts of the Apostles tries to smooth over the disagreements between Peter/James and Paul, attempting to reconcile the two competing Christianities via synthesis.

At the same time, Paul's teachings had come to be equated with those of Simon Magus, the founder of Gnosticism. The Marcionite Gnostics would even come to use solely the Pauline corpus, rejecting the rest of the apostolic literature. In fact, many early Christian writings, such as the Pseudo-Clementine literature, used the name Simon Magus as a cipher for Paul, as if they were two names for the same exact person, equating the teachings of Paul with those of Simon Magus. In reality, Paul and Simon Magus were both pretenders, men who never met Jesus Christ but who claimed to be special authorities on Christianity because of their own prophetic nature: they both claimed to be disciples of Christ via direct divine revelation, even though neither of them had even heard of Jesus until after the crucifixion. The Acts of the Apostles, as a work of revisionist history, recasts Paul as purely in the apostolic tradition rather than a pretender like Simon Magus. Acts goes to great lengths to clearly distinguish Simon Magus from Saul/Paul (cf. Acts 8) and asserts that Paul was a direct disciple of Christ through divine revelation (cf. Acts 9). In the overall revisionist narrative of Acts, Simon Magus is rejected and condemned by Peter while Paul is accepted into the fold and given Peter's blessing. Furthermore, Acts claims that the disagreement between Paul and Peter was smoothed out via divine revelation, when God revealed to Peter in a vision that Paul's interpretation of the gospel was actually the correct one. (Cf. Acts 10) Finally, Acts paints a picture of Peter and all of the Apostles embracing the teachings of St. Paul at the Council of Jerusalem and giving Paul their blessing to spread his version of the gospel. (Cf. Acts 11). All of this is polemical. St. Paul himself acknowledged the conflict between his teachings and those of Peter and James, without any indication that Peter ever came to see things from a Pauline point of view. Ultimately, the narratives of Luke—in both the Gospel and Acts—were quite successful in pulling off this revisionist attempt at synthesizing of Pauline and Petrine Christianity, giving us the "orthodox" Christian narrative we know today.

All of Christian theology, when it comes to the Trinity and the hypostatic union, developed in the context of Neo-Platonist philosophy, attempting to synthesize the ideas of Plato with biblical teachings. Early Christian theology wasn't clearly defined, was quite vague, and really fluid and loose. Even the conception of God as a perfect, all-knowing, and unchangeable being was largely borrowed from Greek philosophy rather than Hebrew scripture. The God of the Old Testament is constantly changing his mind, realizing his own mistakes, and seems to be little more than a primordial incorporeal man with magic powers. It is only when Greek philosophy gets fused with Christian doctrine in the works of Arius, Augustine, et al. that Christian theology as we know it comes into being.

And, contrary to popular belief, Constantine played basically no role in the development of Christian doctrine. He did not preside at the Council of Nicaea, nor did he support either side, and he actually wasn't even a Christian at the time; he didn't convert to Christianity until he was on his death bed. Furthermore, Constantine never made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. All Constantine did was legalize Christianity, just as Judaism had been legalized. This didn't mean that it became the State religion or anything like that; it merely meant that being a Christian was no longer considered a crime to be punished by death, so the Empire stopped burning Christians alive and feeding them to lions in public spectacles.

Christianity wasn't adopted by the Roman Empire as the State religion until Theodosius' edict in 380AD. And the Roman Empire was not even the first nation to adopt Christianity as the official religion. The empires of Armenia and Ethiopia had already adopted Christianity as their official religions by this time. (Of course, Western Christians had to play some revisionist history here because the Armenian and Ethiopian Churches are both Monophysite/Oriental Orthodox rather than Roman Catholic, which sort of implies that the Roman Catholic Church's historical claims are somewhat questionable. History, after all, must be told with a partiality favoring the perspective of the victors.) The Axumite Ethiopian Empire, at the time, was comparable in size, strength, and wealth to the Roman Empire. The first Christian nation, perhaps, historically speaking, was a nation as strong and as great as the Roman Empire, but it was a nation of black people.

Additionally, almost all of orthodox/catholic Christian theology was developed in Africa, where most of the great theologians and monks of the early Church lived. Tertullian, Augustine, Athanasius, Arius, Clement, Origen, Evagrius, Macarius, Poemen, Cyril, Anthony, Pachomius—basically everyone that played an essential role in the development of Christian doctrine and tradition—lived in Africa. Christianity is usually painted as a Western religion, but its earliest origins are in the Middle East and in Africa, not in Europe.

And the Roman Catholic Church, historically, was neither the first nor the largest Christian Church. The bulk of the historic Roman Empire was the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire, which was basically Eastern Orthodox, never having had the distinctly papal and Western doctrines of Roman Catholicism. Most of Western theology is predicated on Neo-Platonist philosophy—and its distinctive features did not exit, and could not have existed, prior to debates between Arius and Augustine. Roman Catholicism is an Augustinian tradition, whereas Orthodoxy/Monophysitism/Nestorianism represent an earlier Christian tradition, somewhat less distorted by secular philosophy. In the 12th Century, the largest Christian Church was the Assyrian Church of the East, which had spread Christianity to the Far East, into India and China. The Assyrian Church of the East had separated from the Western Church (Roman Catholic/Eastern Orthodox) in 431AD, in the schism following the Council of Ephesus. The Assyrian Church clung to Nestorianism. This same Assyrian Church, by the way, still exists today. Then there's the Monophysite (Oriental Orthodox) Church, distinct from the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox, which was rooted in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Israel/Palestine, having rejected the christology of the Western theologians in 451AD. Honestly, to a great extent, the Monophysites (who, by the way, are still around today) have a far more legitimate claim to being the original Church than the Roman Catholics do. But then there's also the hundreds of thousands of ancient Christian sects that are "non-orthodox," which taught Gnosticism or Ebionitism, and had radically different interpretations of Christianity with nothing in common with Catholic/Protestant/Orthodox teachings. These groups, according to early Christian sources, trace back to the first century and stem from the teachings of quasi-apostolic figures that did live while Christ was still preaching. And many of these sects survived up until about the time of the Protestant Reformation. These heresies were criminalized and wiped out through violence.

Thanks for sharing Christian history

that's a lot of information and details you shared from the past interesting :) nice work @ekklesiagora

This is great history for Christian.thanks for sharing @ekklesiagora

Not totally wiped out...There are a handful of us still around:)(:

There are people in those traditions, but no succession or church in those traditions with a lineage going back to apostolic times.

that has to be wiped away from such a community for sure

it has wiped out from community.thats what i can say.

great humanity values could be grasp from this article by you

Wonderfully explained i don't think i can add any value but want to thank you

History is always written by the victors))