The Prisoner's Dilemma in China

A recent science fiction movie from China showed a future where, to save the Earth, the planet needed to be moved. Most of my Western friends asked a simple question – if the technology is sufficient to safely leave the Earth and the Earth will go boom soon, then why stay? However, in China, this is more of a social than a technological question.

In China the social mathematics would be: (family = home = land) X (family = everything).

One does not leave one’s land, notwithstanding the complex effects this has on eminent domain law. One stays. In fact, one barely leaves one’s town for a trip, which is why towns in China that are a short distance away from each other have dialects as different as English is from Estonian. No need to understand someone who doesn’t live by your land. They’re not your people, right?

Decision-making, such as whether to stay on your endangered planet or to leave for safety, is a complicated psychological endeavor, engaging many areas of neural development. This is true in the East as much as in the West. Even deciding what kind of sandwich to order at Subway is no simple feat. Now, add social psychology, where you are not alone in the store.

Imagine that the line behind you in Subway is full of Victoria Secret models, dripping black lingerie and white feather wings. Or maybe the line is filled with the world’s billionaires; Warren Buffet asking about the fundamental value of the ham. Imagine the line contains your ex-lovers, your heroes, enemies, family – any of these people may change how you make decisions – what you order. This is the field of social psychology – how humans behave around other humans.

Social decision-making is arguably the most convoluted of human behaviors. Making decisions with other people around requires simultaneous “games”. This means that each decision in a social situation is based on what you expect someone else to do. Our social decisions are based on the behaviors of others. In improvisational theater, we practice this. However, in Chinese improvisation, the social games that are being played are far different from Western games.

Improvisation is much more than theater. On stage or in rehearsal, we create social situations and then play with them. These situations are sometimes very natural and believable, as in psychodrama (心理剧), or they may be silly and humorous, as in short-form (短片游戏), or may be deeper and contemplative, as with long form (长篇). But our practice should remain truthful.

On stage, it is far easier to make a quick joke rather than to work together. Similarly, in an office or social group, it is tempting to make it seem like the good ideas, the funny jokes or the witty repartee comes from you rather than from the team. Then you would look excellent and you would be remembered. What are the benefits of cooperating with others?

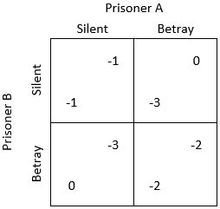

In 1950 at the RAND Corporation in America, two scientists came up with a way to test social decision making called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In this game, there are two prisoners; you and me. The police arrest us both and want to send us to jail, but they don’t have enough evidence, even though we’re actually guilty of the crime.

They put us in two separate rooms and ask us to confess. Here is the situation:

If you are silent and I betray you, I will go free but you will go to jail for 3 years.

If I am silent and you betray me, you will go free but I will go to jail for 3 years.

If we betray each other, we will both go to jail for 2 years.

If we both remain silent, we will both go to jail for 1 year.

On a personal level, it would make the most sense for us to betray each other. That is the most individually rational choice. It would give us each the possibility of going free, allowing the other person to serve three years. However, if we both do that, we both go to jail for two years. The collectively rational choice is for us to both remain silent. Then we both go to jail for one year.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma creates a paradox because individually rational behavior leads to collectively irrational results. The most rational decision for me – the individual – is to betray you. But this is not the most collectively rational behavior. Thus, we have a problem. Do I think about myself or think about us – the collective – the greater good?

To put it the context of theater, or the office, or social life anywhere, trying to show off so everyone thinks you are funny/smart/awesome makes you look good, but may make the team look bad overall. This is similar to the economic theory of the Tragedy of the Commons.

Imagine that you are a fisher and that you discover an excellent fishing technique and the perfect fishing spot. Within a week, you are able to catch almost all the fish from the local lake and sell them. This has a great short-term benefit for you. You make a lot of money. Congratulations.

But your overfishing the lake affects all the other fishers who will then suffer. The lake is common property. Although you have done well in the short-term, society has lost out in the long term. Everyone suffers. Eventually, when there are no more fish, you will suffer too.

In the same way, if you take all the good lines in a show or all the good points at a meeting, then that has a great short-term benefit for you. You look good right now. But it affects the whole team, especially in the long run. The Tragedy of the Commons says that it’s better if you cooperate with all users and, personally, you’ll do better over time.

There’s another reason to cooperate with others rather than stealing the spotlight. That is that social cooperation is actually rewarding to our brain.

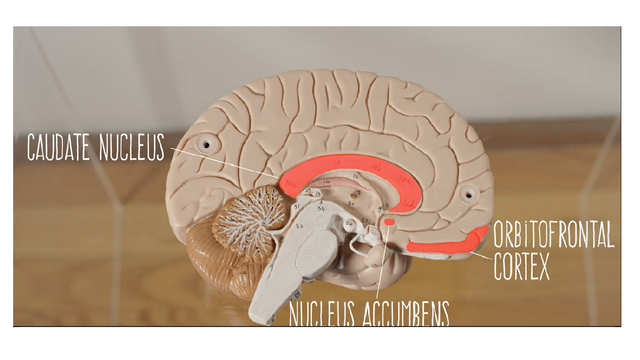

In one study, participants performed the Prisoner’s Dilemma while in an MRI machine. When people cooperated, activation was seen in the caudate nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens. These cerebral areas are linked to reward processing. This means that it actually feels good on a chemical level to cooperate with other people. When people stopped cooperating, these areas of the brain lost activity.

More brain imaging research found that when people cooperate, it increased the firing frequency of dopamine neurons in the mid-brain. Dopamine decreased in firing frequency when people stopped cooperating. This firing of dopamine allows us to learn who is trustworthy.

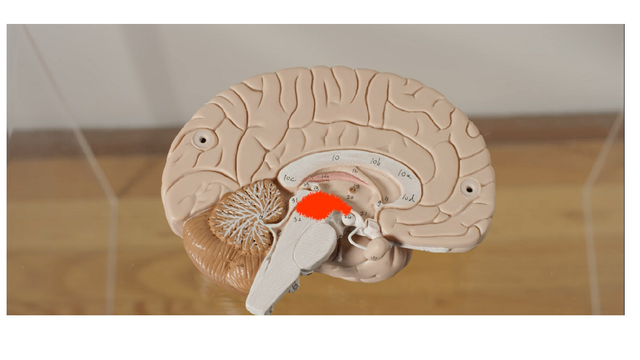

A study from the journal Neuron found that when people made selfish decisions, it affected activity in the temporoparietal junction in the brain. Studies have shown this area affects our ability to make intelligent decisions and to have empathy for others. Therefore, cooperating improves intelligent decision-making.

Now, returning to China, how is this any different from the West? The simple answer is that it’s not. Trust and cooperation physically feel good no matter where you are. The difference, as seen through the lens of improvisation, is that trust and cooperation among people who do not share land is less often encountered in China.

Thus, it is a greater challenge and has a concurrently higher level of achieved beauty, to practice trust and cooperation in a society that is not raised on that. We make the stage our land and share the reality that occurs there. As a Chinese friend shared with me, she was told in elementary school that she should not be friends with any of the other students because her grades were good and they would try to sabotage her – there are only so many seats at each university. She was told this when she was ten. China is a part of the world and the future. It is imperative that the prisoner’s dilemma does not lead to a tragedy in the world commons.

In improvisation, we practice social decision-making. In fact, improvisation may be the only way to get together with strangers and practice an infinite variety of social situations, in pairs and groups, while maintaining a high level of shared reality. Not only is it a fun way to make friends and develop creativity, studies show that this level of cooperation feels rewarding, improves intelligent decision-making and increases empathy. And don’t forget about all the free dopamine.

Lee, Daeyeol. Game theory and neural basis of social decision making. Nature Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group. 2008

Morishima, Schunk, Bruhin, Ruff & Fehr. Linking Brain Structure and Activation in Temporoparietal Junction to Explain the Neurobiology of Human Altruism. Neuron, Volume 75, Issue 1, p73–79, 12 July 2012.

Rilling, Gutman, Zeh, Pagnoni, Berns & Kilts. A Neural Basis for Social Cooperation. Neuron vol.36, p.396-405, July 18, 2002, Emory University, Dept. of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

Rilling, Sanfey, Aronson, Nystrom & Cohen. Opposing BOLD responses to reciprocated and unreciprocated altruism in putative reward pathways. Cernter for the Study of Brain, Mind and Behavior, Department of Psychology, Center for Health and Well Being, Princeton University.

Congratulations @firstdavid! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPVote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!