How did Netflix crush Blockbuster? The importance of business model interaction

(This post by Ramon Casadesus-Masanell & Karen Elterman)

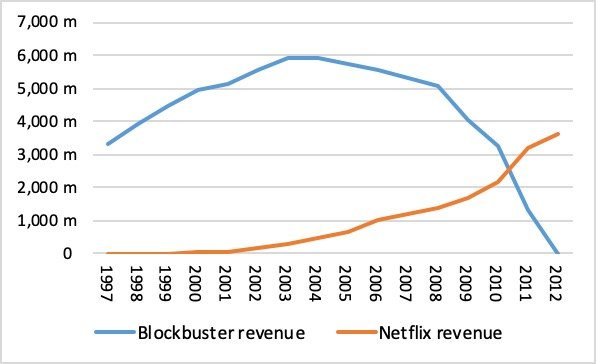

How did Blockbuster go from dominating the video rental market in the early 2000s to being beaten by Netflix and filing for bankruptcy in 2010?

In this post, we strive to answer that question, first by looking at the choices made by Netflix and Blockbuster in the early 2000s, and then by examining the interactions between their business models.

Note: We focus on Netflix’s early success as a DVD-by-mail service. It may be hard to remember now, but Netflix actually got its start in DVD rentals years before streaming services became widespread.

The evolving business model of Netflix

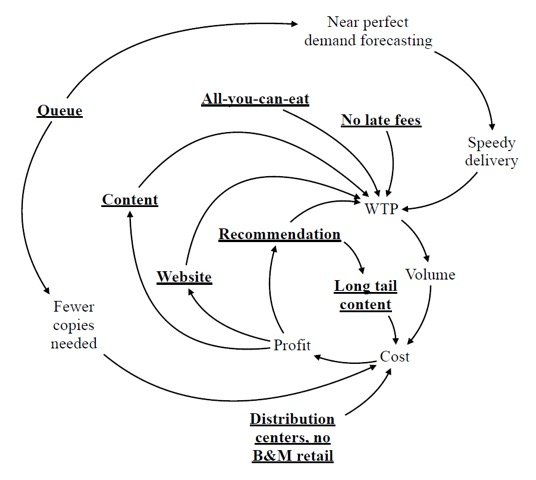

In the early 2000s, Netflix made a number of choices that helped it to create and capture more value. That is, it increased how much customers were willing to pay for its products/services (and was therefore able to charge higher prices), while also lowering its costs of doing business. In this way, it strengthened its value loop – the set of choices and consequences that feed into one another to create a positive cycle of reinforcement that powers a business. By making a series of changes to its business model, Netflix was able to surge past Blockbuster to overtake the home video industry.

Netflix began as a DVD-by-mail business in 1998. Customers could search for DVDs on the Netflix website and build a “queue” to determine the order in which Netflix would send them movies. Customers paid a fee for each DVD they rented and were charged late fees for any movie returned past the due date. For the most part, Netflix worked a lot like a traditional video rental store, only via the mail. So, Netflix had few advantages over rivals like Blockbuster, but it did have a major disadvantage: customers had to wait several days for their movies to arrive.

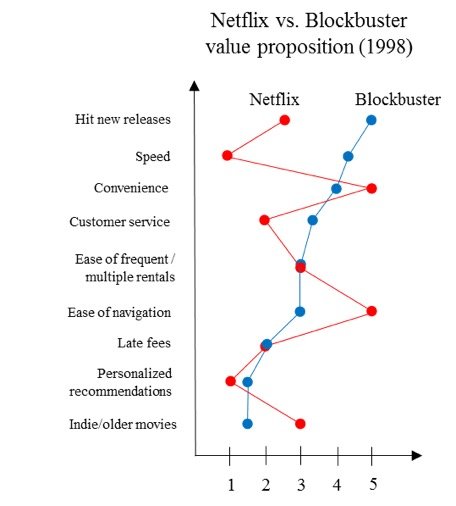

The unique set of features that a company offers to its customers is called its value proposition. The following chart illustrates the value propositions of early Netflix and Blockbuster. Each trait is rated from 1 to 5, where 1 means “poor” and 5 means “great.” You can see from this diagram that on many qualities, Netflix and Blockbuster ranked about the same. However, Netflix did worse in terms of the number of its speed of delivery, customer service, and ability to offer personalized recommendations, as well as the number of hit new releases it carried.

Given its many similarities with Blockbuster, and the downside of waiting for movie delivery, Netflix desperately needed to differentiate itself from its rival. In 1999, it adopted a subscription-based business model. Under this model, instead of paying a fee for each movie rented, customers paid a monthly fee for renting privileges. For $21.99/month, customers could keep three movies at any given time, and exchange them as often as they liked, with no monthly limit. As soon as they returned one movie, they could get a new one in the mail at no additional cost.

Now, Netflix offered something that Blockbuster did not: freedom from late fees. It is hard to overstate how much Blockbuster customers hated late fees, which could easily double or even trip the cost of the original rental, even if a movie was returned only a few days late. By eliminating fees, Netflix gained a concrete advantage it could use to attract customers.

Netflix’s subscription model made it especially appealing to frequent movie watchers, who loved the ability to keep multiple DVDs in their house at once, and to have new movies from their queue sent to them as soon as the previous ones were returned. Customers with busy schedules also appreciated the service, since they did not need to worry about late fees if they could not make it back to a store in time. Already, Netflix’s value proposition was starting to look a lot different than Blockbuster’s. And over the next few years, it took a number of steps to further improve its business model:

Personalized recommendations. First, Netflix developed a personalized recommendation system based on a proprietary algorithm and movie ratings data gathered from customers. A filter ensured that the system only recommended movies that were currently in stock. As a result, the company shifted away from hit new releases toward a “long tail” of indie and older movies, which lowered Netflix’s costs, since indie movies were less expensive to acquire than blockbuster films.

Relationships with movie studios. In 2000, Netflix changed the way it acquired movies, developing revenue sharing agreements with the major studios. Under these agreements, instead of paying a high up-front cost for DVDs, Netflix acquired them at lower prices, but paid the studios an additional fee based on how many times each movie was rented out in a given period. This system was actually slightly more expensive for Netflix, but resulted in much higher customer satisfaction, as Netflix was able to acquire more copies of any given film and make popular movies more available. The company also became a valuable partner of independent studios, growing its indie movie selection.

The queue. Netflix’s queue (not a new feature, but one it maintained) provided the company with a near-perfect demand forecasting system, since it could see how many people would want a particular DVD months into the future. As a result, Netflix was able to make efficient use of its national inventory.

Distribution. Netflix continuously added distribution centers across the country. It also struck up a close relationship with the US Postal Service, which helped it expedite deliveries and returns. By 2009, Netflix was able to deliver to most of its subscribers within one day.

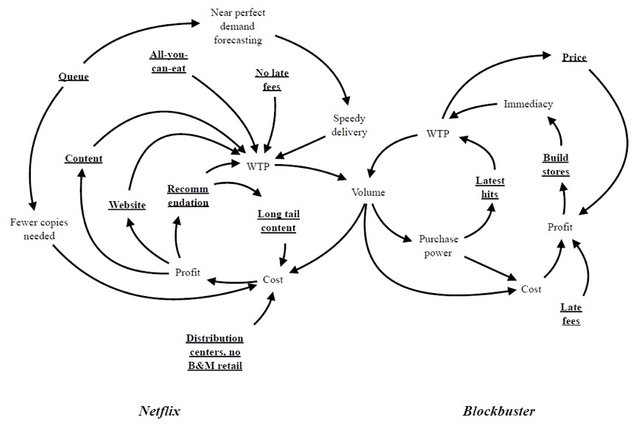

By implementing these changes, Netflix created a number of positive feedback loops in its business model that helped it to create and capture value. The following is a representation of its business model in 2010:

The changes implemented by Netflix also helped it further differentiate from competitors like Blockbuster. The diagram below shows the value propositions of the two companies in 2006:

Netflix now appealed to a different set of customers than Blockbuster—namely, those who valued a wide selection of indie films, the ability to get movies without driving to a store, and perhaps most importantly, freedom from late fees.

Response by Blockbuster

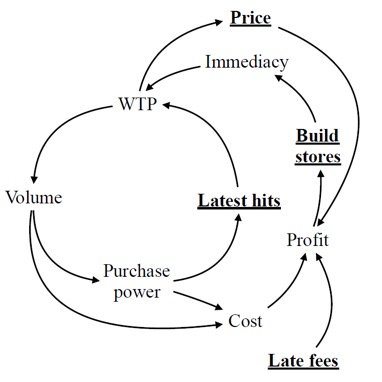

Blockbuster’s early success was built on close proximity to the customer and a relatively limited but well-stocked selection of films, with an emphasis on hit new releases. The diagram below shows Blockbuster’s business model in 1999.

Blockbuster made a number of poor decisions in combatting the threat of Netflix. Its response to Netflix—or perhaps more accurately, its failure to respond—can be thought of in terms of four “internal barriers to response,” a framework first developed by Professor Jan Rivkin at the Harvard Business School.

1. Perception – Failure to recognize a threat

In 2000, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings proposed a partnership with Blockbuster in which Netflix would run Blockbuster’s online brand, while Blockbuster promoted Netflix in its physical stores. Blockbuster CEO John Antioco laughed him out of the room. This is perhaps not surprising, given that Blockbuster then had about 4,300 stores in the US, and revenues of nearly $5 billion, compared to only $36 million for Netflix. In retrospect, however, Blockbuster’s apparently strong position caused it to overlook Netflix as a major threat. As late as 2002, a Blockbuster spokesperson stated that the company did not see Netflix’s business model as being viable in the long term, and that Netflix was serving “a niche market.”

2. Motivation – Recognizing a threat but not wanting to respond

In 2004, CEO John Antioco developed a plan to spend $200 million launching an online business, plus $200 million eliminating late fees. However, Blockbuster’s parent company, Viacom—which then owned 80% of Blockbuster–was wary of this $400 million investment. In 2004, it sold its stake in the company, which became publicly held. This caused Blockbuster’s share prices to fall, which paved the way for the investor Carl Icahn to buy nearly 10 million shares in the company in 2005, becoming its biggest shareholder.

In January of 2005, Blockbuster eliminated late fees on DVD rentals across all of its stores. This change led to a 5% increase in rental revenue, but lost the company $600 million in annual revenue from late fees. Icahn believed that the elimination of late fees had been a mistake. Not only had it lost the company money, but it caused the most popular DVDs to be frequently unavailable, since customers often held on to them past the due date. When Antioco left the company in 2007, management appointed a new CEO, Jim Keyes, who walked back many of the changes the company had made, refocusing the company on its store-based business.

3. Inspiration – Wanting to respond but not knowing how

Blockbuster tried several initiatives to combat Netflix. In 2004, it introduced a subscription service called Movie Pass, which allowed customers to make unlimited rentals at Blockbuster stores with no late fees. However, Movie Pass required customers to pick up and return the DVDs at Blockbuster’s physical stores. Later that year, the company introduced Blockbuster Online, an unlimited subscription service that more closely resembled that of Netflix. Under this service, customers received DVDs by mail, and had to return them by mail as well. It was not until 2006, when Blockbuster introduced a program called Blockbuster Total Access, that subscription customers could choose to exchange DVDs either by mail or in a store.

Although Blockbuster now had a sense that some change was necessary, its path forward was not entirely clear. Even while it experimented with an online business, it was also ramping up its focus on physical stores. In the early 2000s, Blockbuster steadily expanded its in-store video game business, purchasing the British chain Gamestation in 2002 and the US-based Rhino Video Games in 2004. It even considered buying the struggling electronics retailer Circuit City, which went bankrupt in 2009.

By 2008, competitors such as Netflix, Amazon, and Microsoft all had the capability to deliver movies directly to customer PCs, while several other companies offered video on demand by TV. Blockbuster, however, had no streaming offering. Although the company did test some new technology initiatives, such as a TV set-top box for digital downloads and an in-store kiosk for downloading movies to a customer’s laptop, it ultimately failed to establish a clear path forward, and found itself falling behind its rivals.

4. Coordination – Seeing a way to respond but being unable to implement it

Many of the changes made by Blockbuster’s management team failed because they did not take other business model components into account. For instance, when Blockbuster eliminated late fees, it still relied heavily on its traditional business, for which late fees had been a major source of revenue. As a result, it was hit hard by the loss of funds. It also suffered from stockouts, since customers had no incentive to return movies on time. In contrast, when Netflix eliminated late fees, it did so as part of the restructuring of its entire business model. It did not need the revenue from late fees, because its subscription model provided a regular source of income. Likewise, its long tail of movies made it ok for customers to hold on to DVDs for a long time. Thus, Blockbuster’s story illustrates the interconnectedness of business model choices, and the importance of coordinating changes throughout the company.

In 2009, Blockbuster suffered losses of $517 million and closed nearly 1,000 stores in an attempt to return to profitability. By September 2009, its DVD-by-mail business had shrunk to about 1.6 million subscribers, down from a previous height of 3 million, and by 2010, it had filed for bankruptcy. It was later acquired by Dish Network.

The importance of interaction

Blockbuster and Netflix interacted in a fairly straightforward manner, as competitors fighting over market share. Their business models overlapped mainly at the point of volume—the more customers Blockbuster took, the fewer Netflix was likely to have, and vice versa. Nevertheless, we can learn several things from the interaction between these business models, which is illustrated by the diagram below:

Cost structures and revenue models determine how each company is affected by customer volume

Once Netflix had adopted its subscription model, it appealed largely to a different segment of customers than Blockbuster (broadly, film buffs who were willing to wait for a wider variety of films, rather than customers who wanted hit films ASAP). Given the different target segments of the two companies, one might ask, “Why should Blockbuster be worried about Netflix?” After all, Netflix was not likely to attract the people who most valued what Blockbuster had to offer. The answer to this question has to do in part with the cost structures of the two companies.

Due to the nature of its business model, Netflix had relatively low fixed costs, and high variable costs. Its fixed costs included marketing expenses, warehouse upkeep, and the IT costs associated with its website and recommendations algorithm, but these were spread out among the millions of DVDs it owned. More importantly, it did not have to pay for any physical retail space. As a result, the majority of its costs were the variable costs associated with sending out individual DVDs, such as packaging and postage costs. A large portion of the revenue from any one rental was spent on getting that rental to and from the customer.

Blockbuster, on the other hand, was largely a fixed cost business. Blockbuster had slightly lower marketing and IT expenses (since it was already a household name and did not have a complex website to maintain), but it had huge fixed costs associated with its thousands of stores. Blockbuster had to rent or buy the property for these stores, maintain their appearance and cleanliness, and pay the wages of thousands of store employees. At the same time, there was little variable cost associated with each individual rental, since customers would simply come to the stores and pick out their desired DVDs. Thus, for every DVD Blockbuster rented, a large portion of the revenue went to the company’s fixed costs. This cost structure was harmful to Blockbuster, because when volume decreased, its average total cost went up very quickly.

Since Netflix’s costs were mostly variable, decreases in volume did not have a major effect on its total costs. When it missed out on a rental, it avoided the costs of packing and shipping a DVD. Moreover, because Netflix was a subscription service, it might actually benefit if Blockbuster stole some of its rental volume, as long as the customer did not cancel their subscription. For example, a Netflix customer might choose to rent one particular new release from Blockbuster, without unsubscribing from Netflix. In this case, Netflix would still make money off that customer from their subscription fee, but would not have to pay the variable costs associated with fulfilling an order.

The situation was reversed for Blockbuster, whose business model was less resilient than that of its rival. Since Blockbuster’s main source of revenue was individual rental and late fees, it relied heavily on DVD rentals to help spread out its fixed costs. As a result, Netflix only needed to take a small share of Blockbuster’s revenues in order to be a major threat. Perhaps if Blockbuster had taken this into account, it would have moved more aggressively against Netflix, e.g., by making earlier changes to its business model and more readily pursuing new technologies, rather than letting Netflix gradually steal from its customer base.

Even in a relatively straightforward case of competition, where two companies interact mainly in terms of a tug-of-war for market share, the nature of each company’s business model can have major implications for how the choices of both companies play out. When considering a path forward, Blockbuster failed to consider the interactions between its business model and that of Netflix, which ultimately contributed to its downfall.