Convicts and colonisers: the early history of Australia

Booker Prize-winning author Thomas Keneally speaks to Rob Attar about the early history of his home country, Australia, discussing the remarkable progress of Britain's "sunstruck dungeon" at the end of the world

Thomas Barrett was sentenced to death three times. His first capital offence was in 1782 when, as a young boy, he was found guilty of stealing a silver watch in London. Barrett’s sentence was commuted and he was despatched instead to the North American colonies. However before his ship had left Britain there was a convict uprising that enabled Barrett to escape. His freedom was short-lived. Barrett was recaptured and the death penalty was again handed down for his actions. But for a second time royal intervention saved him from the noose. And so it was that in 1787 Thomas Barrett found himself a passenger on the Charlotte, as part of the first fleet that shipped prisoners to the distant land of Australia. There his final sentence still awaited him.

Barrett’s story illustrates a key idea to emerge from Australians, the first part of Thomas Keneally’s epic history of a continent and its people. The nature of the early immigrants meant that this was a colony like no other. “If you’ll accept that we’re a sophisticated society (which is hard for the British to do) then you’d have to say that this is the only advanced country on earth that began as a purpose-designed penal colony,” says Keneally. “It didn’t begin as a place where there were settlers who used convicts. It began as a jail.”

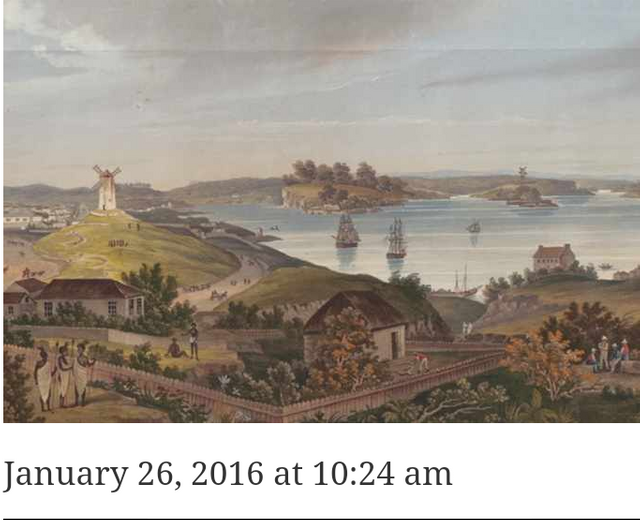

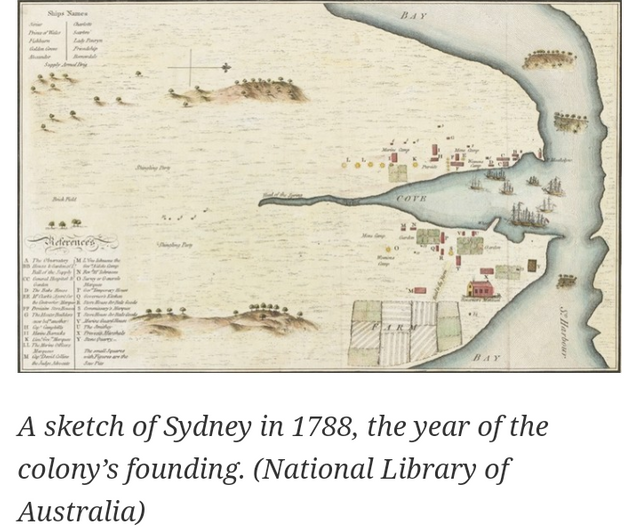

Having been deprived of American colonies following the emergence of the United States, Britain in the 1780s was desperate to find an alternative territory for its miscreants. Australia, recently claimed for the empire by Captain Cook, seemed to fit the bill. It had been inhabited by Aborigines for millennia but, despite a few tentative voyages, no other European power had established a lasting settlement on the continent. Britain took the lead. The first fleet of convicts arrived in January 1788 and a fledgling penal colony was established in what is now Sydney.

Who were the people who landed on what Keneally describes as “a sunstruck dungeon at the end of the world”? They were prisoners, yes, but they weren’t just a group of common criminals. “One of the reasons early Australia survives was that there were many social protestors among the convicts,” explains Keneally. “These were people who did not consider themselves criminals. They were people like poachers who acted in protest against the enclosure of estates. Then there were Luddites, Swing rioters, Irish Ribbonmen and Jacobite martyrs. You had these fairly robust, stroppy people alongside the professional thieves and prostitutes.”

Land of the free

Within a few years, convicts were joined by free people from Britain and Ireland (and later other parts of Europe), attracted to dreams of a better life. These emigrants went out further than the areas the colonial authorities could control and squatted on huge tracts of land. Some were inspired by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who, while languishing in Newgate prison in the 1820s, wrote an influential pamphlet encouraging yeomen to settle Australia.

Nor was it just the poorer Britons who headed for Australia, according to Keneally. “Australia has always been the place to which Britain has sent unsatisfactory members of all its classes, including the gentry and bourgeoisie. It was a great place to send young men who had gambling debts or had been cashiered. It was also the sort of place where you sent bluff English lads who weren’t particularly good academically, or who had impregnated the maid. Charles Dickens, for example, sent his two dumbest sons to Australia and Trollope had a son there as well.”

In many ways the early history of Australia is hard to detach from the story of its mother country. The kinds of people, settler and convict, who came to the continent reflected the social and political situation in Britain at the time. “It provides,” says Keneally, “an acute focus on the problems of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.”

Whether they departed in fear or hope, the Britons and other Europeans who arrived in Australia faced a forbidding landscape. In a continent with little water and variable soil, the development of agriculture was extremely difficult. The interior in particular offered little bounty and despite several expeditions, no great river like the Mississippi could be found. Instead many explorers perished in the desert heat.

“The settlers brought with them their Eurocentrism and they didn’t realise how dry this continent was,” explains Keneally. “British yeomen tried to advance into South Australia and Western Australia but it was impossible because these places are deserts. It showed a great incomprehension of the country that they were coming to. These folk should have perished on the desert shores and in many cases they came close to doing so. They also went mad and committed suicide, but ultimately they stayed. They stayed and endured.”

In the perilous early days of New South Wales (as British Australia was originally known), food stocks frequently dwindled and rations fell. It was only the arrival of supply-laden ships from Britain that enabled the colony to continue. However, although farming was tricky, the settlers discovered that the climate was suitable for livestock and especially sheep. Useful for their meat and wool, sheep farming had become a mainstay of the Australian economy by the middle decades of the 19th century.

As settlements expanded they came into greater conflict with the Aboriginal people who had lived in Australia for at least 50,000 years. This was, Keneally believes, “the countervailing tragedy” of Australian history. “The Aborigines considered that the country was theirs and any animals on it were theirs as well. So they began killing the livestock of settlers, and maybe they would also kill a convict shepherd because he was messing with their women or had stolen stuff from them. This is when the carbines came out and, when it came to a showdown, our technology and firepower was greater.”

Through frontier wars, massacres and the introduction of diseases, the Aboriginal population was devastated. The settlers took over swathes of territory, effecting a cultural as well as physical dispossession. “We can lose our house in the suburbs that we’ve had for 20 years and we’ll sort of survive,” says Keneally. “But if you separate the Aboriginals from their traditional land, which is their source of food and social cohesion, then you are depriving them of more than real estate.”

Nor was it just the poorer Britons who headed for Australia, according to Keneally. “Australia has always been the place to which Britain has sent unsatisfactory members of all its classes, including the gentry and bourgeoisie. It was a great place to send young men who had gambling debts or had been cashiered. It was also the sort of place where you sent bluff English lads who weren’t particularly good academically, or who had impregnated the maid. Charles Dickens, for example, sent his two dumbest sons to Australia and Trollope had a son there as well.”

In many ways the early history of Australia is hard to detach from the story of its mother country. The kinds of people, settler and convict, who came to the continent reflected the social and political situation in Britain at the time. “It provides,” says Keneally, “an acute focus on the problems of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.”

Whether they departed in fear or hope, the Britons and other Europeans who arrived in Australia faced a forbidding landscape. In a continent with little water and variable soil, the development of agriculture was extremely difficult. The interior in particular offered little bounty and despite several expeditions, no great river like the Mississippi could be found. Instead many explorers perished in the desert heat.

“The settlers brought with them their Eurocentrism and they didn’t realise how dry this continent was,” explains Keneally. “British yeomen tried to advance into South Australia and Western Australia but it was impossible because these places are deserts. It showed a great incomprehension of the country that they were coming to. These folk should have perished on the desert shores and in many cases they came close to doing so. They also went mad and committed suicide, but ultimately they stayed. They stayed and endured.”

In the perilous early days of New South Wales (as British Australia was originally known), food stocks frequently dwindled and rations fell. It was only the arrival of supply-laden ships from Britain that enabled the colony to continue. However, although farming was tricky, the settlers discovered that the climate was suitable for livestock and especially sheep. Useful for their meat and wool, sheep farming had become a mainstay of the Australian economy by the middle decades of the 19th century.

As settlements expanded they came into greater conflict with the Aboriginal people who had lived in Australia for at least 50,000 years. This was, Keneally believes, “the countervailing tragedy” of Australian history. “The Aborigines considered that the country was theirs and any animals on it were theirs as well. So they began killing the livestock of settlers, and maybe they would also kill a convict shepherd because he was messing with their women or had stolen stuff from them. This is when the carbines came out and, when it came to a showdown, our technology and firepower was greater.”

Through frontier wars, massacres and the introduction of diseases, the Aboriginal population was devastated. The settlers took over swathes of territory, effecting a cultural as well as physical dispossession. “We can lose our house in the suburbs that we’ve had for 20 years and we’ll sort of survive,” says Keneally. “But if you separate the Aboriginals from their traditional land, which is their source of food and social cohesion, then you are depriving them of more than real estate.”

Very interesting your post friend@ mizanrahman. Regards ; )

Thanks a lot dear from bottom of heart again thanks for visiting my blog bro im new in steemit want support as a bro @josue07

Good posting! I visit your blog ^^ Have a nice day~!

Thanks a lot dear i likes you very much @onepine