Appendix N Review: Three Hearts and Three Lions

To Holger Carlsen, Dane by birth and engineer by trade, science rules all. The immutable laws of physics govern the universe, and there is no space in this rational world for the mysterious and the magical. Yet one fateful day, when fighting along the Resistance in the Second World War, he is knocked out in battle, and awakens naked in a strange forest. Nearby is a horse of startling intelligence, carrying arms and armour that fit him perfectly, including a shield that bears the device of three hearts and three lions.

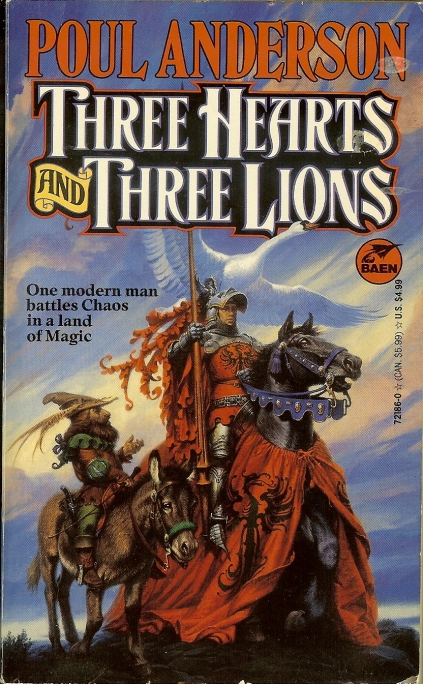

Thus begins Poul Anderson's seminal work Three Hearts and Three Lions. Coming from an era saturated with Japanese isekai stories and Western dark fantasy CRPGs, Three Hearts and Three Lions is simultaneously refreshing and inspiring. Both of these media owe their origins to Gary Gygax's Dungeons & Dragons tabletop roleplaying game, and Gygax in turn drew inspiration from a list of stories, stories he listed in his famous Appendix N. Among them is Three Hearts and Three Lions.

Before the isekai boom, before the fad of Western dark fantasy, there was the traditional Western fantasy in all its glittering splendor. Three Hearts and Three Lions hails from that era, seamlessly weaving myth and religion into a tale of chivalry and romance.

Holger Carlsen is not on Earth anymore -- and yet this Earth bears startling similarities to ours. There is talk of Charlemagne and Saracens and Jews, but there are also fairies, pagans, monsters, demons, and the Dark Powers that rule the forces of evil. Magic is accepted reality, but scientific principles also underline the world. Holger has no knowledge of the language of this world, yet when people speak he hears his own tongue, and when he speaks the words that emerge are those of this other world. Most curiously of all, Holger's name is known far and wide across the land as a Champion of the Law.

As Holger attempts to understand how and why he was brought to this world, he joins forces with a beautiful swan maiden and a stout dwarf. Together, they embark on a journey to discover his identity, uncover the significance of the three hearts and three lions, and save both worlds from the forces of Chaos.

Fans ofD&D, Western fantasy and isekai can clearly identify the progenitor of many themes and tropes within this book. There are monsters taken from myth, the hero who applies modern-day knowledge in a fantasy setting, elves and dwarves and demons, the archetypal paladin who wanders the world doing good and smiting evil, and so on. Admiral Ironbombs does a commendable job here linking Three Hearts and Three Lions to D&D.

But there is one thing that many modern fantasies have not inherited from classical fantasy, something that is readily apparent in every page of Three Hearts and Three Lions: religion.

The world of Three Hearts and Three Lions is divided into Law and Chaos. As Jeffro Johnson discussed, they represent different polarities and different ways of life. Law is civilization, selflessness and predictability; Chaos is selfish, unpredictable and subversive. The lands of the Law belong to humans -- religious humans -- while the domain of Chaos belongs to the Fae and their vassals. Caught in between are the Middle Worlders who adopt a policy of neutrality.

In a direction confrontation with the forces of the Law, Chaos is impotent. The touch of silver or cold iron, the sight of a crucifix, or a sincere prayer will repel the forces of Chaos. Faith alone is the ultimate weapon against Chaos. Instead of direct confrontation, Chaos relies on a strategy of subversion, breaking the will of the inhabitants of the Law to spread their power. Chaos relies also on recruits from the neutral creatures of the Middle World. While lacking the magical powers of Chaos, Middle Worlders are not vulnerable to iron, silver or holy symbols, enabling them to battle the forces of the Law directly.

Such a conflict is reminiscent of Ephesians 6:12 ("For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places"), a battle of wills and faith instead of flesh and steel. When waging war on Chaos, you aren't just placing your life at risk -- you risk your soul.

In the world of Three Hearts and Three Lions, the Fae are cunning, seductive and manipulative beings who tempt their enemies into ruin. A prayer and a cross can ward you from demons in the dark, but a single impious thought will break the wards, and the tireless monsters of the night will fall upon you. Scenes like this resonate sharply with Christian readers, and yet it is presented as an organic aspect of the world, so non-Christians do not feel like they are being lectured to.

Contrast this with many modern fantasy stories, isekai or otherwise. The Church -- or any kind of centralised religion -- is usually nonexistent, a target of ridicule, or an evil and oppressive organization that must be destroyed. The forces of evil are powerful and innumerable, sweeping across the land like an infernal scourge. The enemy is known and readily identifiable. The hero is usually either a displaced shounen with overpowered cheat skills, a designated hero only slightly less evil than the Big Bad, or both.

Such a setting ignores or denounces the concept of a central moral authority. Morality thus stems from the characters' personal code of conduct, or relies heavily on the perspective the consumer brings to the table. Lighter works like Death March to the Parallel World Rhapsody have the heroes act generally according to accepted modern moral norms, without exploring the moral dimension. Darker or more mature works attempts to undermine the notion of objective ethics altogether. For instance, in Tsuyokute New Saga, protagonist Kail will do anything -- lie, cheat, manipulate and murder -- to attain his goal of defeating the Demon King, and suffers no consequences or guilt from his deeds.

Stories that lack a moral dimension tend to become predictable. The main character begins by fighting small fry, and as he becomes more powerful, the bad guys become increasingly dangerous and the stakes ever higher. Past a threshold, there is no longer any excitement from fighting lesser scum, for the reader knows that the hero will steamroll them. The writer knows this too, so the only way to keep things interesting is to either expand the cast of characters or to shoot for the highest stakes: to defeat the Big Bad and save the world.

While there is nothing inherently wrong in escalating stakes, in one paragraph I've described nearly every major shounen and seinen fantasy story of the last twenty years.

Stories where morality has consequences and religion has weight carry a gravitas unknown to the previous category. Religious institutions and rituals meaningfully contribute to the world, adding layers to the setting and influencing the events of the story. Indeed, Christian rites and beliefs influence the inhabitants of the world of Three Hearts and Three Lions in ways minor and major. When faced with critical decisions, characters must weigh their options and act appropriately.

When good and evil both have costs and advantages, every decision has impact and significance. From a craft perspective, you don't have to keep coming up with ever-more-exciting setpiece sequences to keep the audience interested; you can always switch things up by making the character make a difficult choice.

Stories in which an ever-increasingly powerful protagonist merely faces mortal peril must eventually fall back on spectacle and action extravaganzas to make continued conflict meaningful to the audience. Stories that place the hero in mortal and moral peril require the hero to guard his soul from corruption every step of the way. The latter doesn't need a Demon King, a horde of cannibal barbarian warriors, or slavering eldritch abominations from Beyond to keep things exciting -- when the hero must constantly struggle with his inner demons, a single misstep will leave him naked to the forces of Hell. Such a setting allows for fresh stories, meaningful drama and compelling arcs -- and prevents the hero from being trapped into a never-ending loop of beating up foes, getting stronger, and beating up even stronger foes ad infinitum.

Most of all, in stories with a positive portrayal of religion, a skilled writer can drop the veil at the right moment, revealing exactly where the protagonist stands in the grand cosmic design and how he touches the lives of everybody and everything around him. It is a powerful moment that affirms the value of the good life and inspires awe and wonder in the reader. This is the moment of awe the Superversive movement strive for. And the climax of Three Hearts and Three Lions does this beautifully.

With the hero facing mortal and moral peril, Christianity as a powerful force for good, tireless evil that hunts patiently for souls, fantastic creatures and marvellous characterisation, Three Hearts and Three Lions is a worthy addition to any fantasy library. It is a seminal novel that upholds the pillars of Western civilization, yet speaks to readers of every creed. Quite simply, it is one of the finest fantasy stories of the twentieth century.

--

My own stories also conspire to place the hero at mortal and moral peril. Check out my latest novel HAMMER OF THE WITCHES here.

Reading this novel was beyond refreshing for me. Its old-fashioned sense of morality was beautiful; I knew no such work could be published by a mainstream publisher today.

A book like this is too unironically righteous and beautiful for the industry.

I haven't read much Anderson. I didn't realize he was such a religious writer.

I'm not particularly religious myself. Like Vonnegut (and this is really the only way I'd ever dare to compare myself to the great writer) I'm more of a Jesus loving athiest. But I've got to say there's something moving and deeply exciting about Catholicism as a body of poetry, ritual, and belief. I think the protestants (so prominent in New England, of course) lost a lot when they moved into their austere and simple churches.

It's also why the biggest fans of horror movies in America are Catholics and Blacks. The Blacks have this wild tradition of yelling at the screen and almost participating in the movies. The Catholics are more inspired by the idea that hell is real, and horror reflects what, to them, are perfectly rational fears of the afterlife.

You have me wishing I hadn't sold my 1st edition AD&D books after high school. Do you play? Did you read those big manuals in English or were they available in Mandarin?

Catholicism carries with it a centuries-long tradition of devotion, beauty and rigorous thought. I can see its appeal to so many people, and how Christianity as a whole became a bulwark of Western civilisation.

Tabletop RPGs never really took off here. D&D wasn't a part of popular culture in Singapore the same way it did in the West. Tabletop gaming only recently grew roots here, mostly through Warhammer.

However, for some mysterious reason, my family owned several D&D computer games: Pool of Radiance, Curse of the Azure Bonds, Secret of the Silver Blades, Pools of Darkness, Eye of the Beholder and Hillsfar. I spent many, many hours reading through the manuals, understanding the arcana of character creation, attempting to piece together stories, and studying the monsters. I don't have those games any more...but they left their mark. I think I can safely say that I was the only student in my class, arguably even the school, who wrote D&D-inspired stories as part of homework.

POOL OF RADIANCE! That takes me back. On a ten year old IBM PC clone with CGA monochrome amber graphics. No hard drive, so constantly switching out the 5.25" disks. "You see a group of seedy looking kobolds..."

I feel kind of bad you didn't have a group of friends to game with. But "geeking out" over the manuals must have been a great form of escapism, nonetheless.

It was. And those manuals had the side effect of informing my own work.

Those were the days, eh.

They really were. We were an odd band of misfits, toting around our monster manuals until the last day of school.

Definitely will have to check out this novel now.

As you were describing the typical postmodern, amoral fantasy, I couldn't help but think of the stereotypical videogame: the little battles leading up to the level bosses, all preparing for the big boss at the end. Besides the graphics, the feel is nearly always the same. It's only the spectacle (the graphics and little tweaks in the game mechanics) that changes.

Which now has me curious what a game design that took religion and morality seriously might look like...

Good review!

Thanks!

Yes, much postmodern amoral fantasy read like video games... and many of them are litrpgs to boot. There's really only so many stories involving stat-powered adventurers hunting Demon Lords you can read before they blur into an undifferentiated mass.

I think Gary Gygax tried to account for religion and morality in his D&D games through the alignment system. I know the PulpRev guys are running a tabletop RPG that takes morality seriously.

As for myself, I do have game designs that take religion and morality EXTREMELY seriously... And one day I might just be able to realise them in some form.

Have you read The Broken Sword, which is also by Mr. Anderson?

It's on my to-read list.

Upvoted. Please follow @amfeeds if you like my content .Upvote, comment, resteem are much appreciated!