The Sensations That Drive Economic Growth

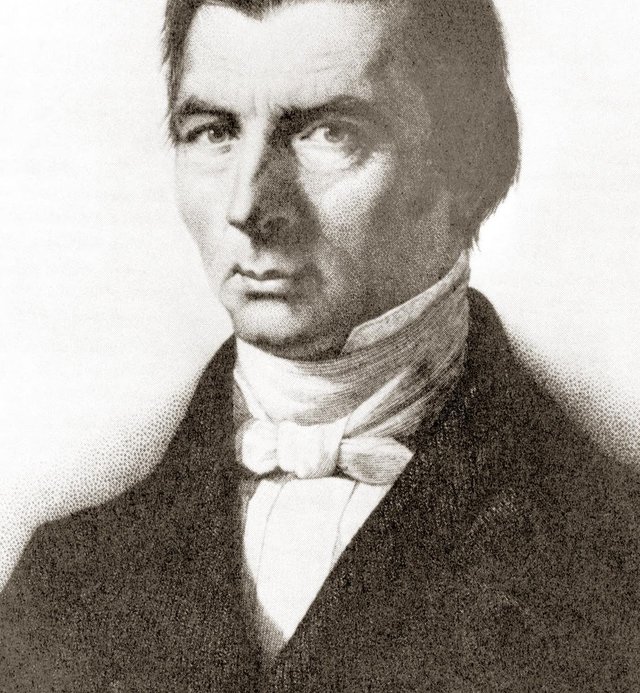

[Originally published in the Front Range Voluntaryist, article by Scott Albright. This is the second segment (chapter two) in our series of breaking down chapters of Frederic Bastiat's Economic Harmonies. See chapter one's review here]

Chapter two delves into the cause and effect of satisfying wants by explaining actions determined by subjective valuations of ends and how their fulfillment comes about. Man has scarce resources to utilize as means to his ends. It is only natural that he desires to harness the forces of nature to ease his efforts and make them more productive so that he can have both more leisure and time to pursue the satisfactions of ever-changing, newer, more refined wants.

"The soul (or, not to become involved in spiritual

questions, man) is endowed with the faculty of

sense perception. Whether sense perception

resides in the body or in the soul, the fact remains

that as a passive being he experiences sensations

that are painful or pleasurable. As an active being

he strives to banish the former and multiply the latter.

The result, which affects him again as a passive being,

can be called satisfaction." [1]

In light of the chapter title, "Wants, Efforts, Satisfactions", it is very important to note that the sensations of want and satisfaction are most often in society felt by one individual, but the effort is mostly performed (and therefore felt) by others in terms of the satisfactions that we enjoy but do not produce directly, because we rather are most likely a producer of one or a limited number of other goods and/or services that we produce in order to exchange for. With an expanded division of labor and growth in capital accumulation, man is able to satisfy his wants on continually better terms and therefore, fulfill more wants he formerly did not have as new ones emerge. It is only in the state of isolation that man always feels all three of these sensations; wants, efforts, and satisfactions.

"Of the three terms that encompass the human

condition – sensation, effort, satisfaction – the

first and the last are always, and inevitably,

merged in the same individual. It is impossible

to think of them as separated. We can conceive

of a sensation that is not satisfied, a want that

is not fulfilled, but never can we conceive of a

want felt by one man and its satisfaction

experienced by another…If the same held true

of the middle term, effort, man would be a

completely solitary creature. The economic

phenomenon would occur in its entirety within

an isolated individual. There could be a

juxtaposition of persons; there could not be

a society. There could be a personal economy;

there could not be a political economy." [2]

Chapter two also, as well as many others in Bastiat's Harmonies, elucidates the importance of human action and free will in studying economics; that logic and deductive reasoning can be traced from the axiom of action to show causal relationships crucial to understand in order to shed light upon the harmonies of capital.

"We are endowed with the faculty of comparing,

of judging, of choosing, and of acting accordingly.

This implies that we can arrive at a good or a bad

judgment, make a good or a bad choice—a fact

that it is never idle to remind men of when we

speak to them of liberty." [3]

In my opinion, the most captivating point in chapter two is the unique description of how man's wants are satisfied: There are two cooperating factors, the first comes from Providence, gifts of nature, termed “gratuitous utility” by Bastiat, such as water, rainfall, sunlight, electricity, minerals in the earth, land (in it's natural state), or anything that human labor has not produced. The second factor is “onerous utility”, any human labor performed or services exchanged that are part of the production process.

"If we give the name of utility to everything that

effects the satisfaction of wants, then there are

two kinds of utility. One kind is given us by

Providence without cost to ourselves; the other

kind insists, so to speak, on being purchased

through effort. Thus, the complete cycle

embraces, or can embrace, these four ideas.

...Our self-interest is such that we constantly seek

to increase the sum of our satisfactions in relation

to our efforts; and our intelligence is such—in the

cases where our attempt is successful—that we

reach our goal through increasing the amount of

gratuitous utility in relation to onerous utility.

Every time progress of this type is achieved, a part

of our efforts is freed to be placed on the available

list, so to speak; and we have the option either of

enjoying more rest or of working for the satisfaction

of new desires if these are keen enough to stir us

to action. Such is the source of all progress in the

economic order." [4]

This passage describes part of the essential thesis of the book and what it entails, of man's desire to better his lot in life, have more leisure at his disposal and newer, more refined wants satisfied. One often overlooked factor from free markets and innovative capital investment is that it frees up labor to pursue newer, more advanced and higher order talents that emerge in the market as newer wants desired by consumers emerge in the market. This is good both for producers and consumers.

This is how man, in his self-interest, pursues his ends. But it doesn't end here. When man is successful in harnessing the forces of nature to utilize more efficiently the scarce factors of production necessary to yield desired satisfactions from his efforts, he not only benefits himself but society as a whole. Provided exchange is voluntary and competition is unleashed, that man is free to pursue his ends so long as he does not initiate force against the person or property of others, these benefits extend to the employees in their capacity as workers from increased output per worker, productivity gains resulting in higher living standards, more leisure and time to pursue new, unfulfilled wants. Consumers also benefit from more choices, higher quality, lower prices, and having more purchasing power so that they can consume and/or save/invest more of their income as well as fulfill new wants that they did not formerly have.

"I have just defined political economy and

marked out the area it covers, without

mentioning one essential element:

gratuitous utility, or utility without effort.

All authors have commented on the fact that

we derive countless satisfactions from this

source. They have termed these utilities, such

as air, water, sunlight, etc., natural wealth, in

contrast to social wealth, and dismissed them;

and, in fact, since they lead to no effort, no

exchange, no service, and, being without value,

figure in no inventory, it would seem that they

should not be included within the scope of

political economy.

This exclusion would be logical if gratuitous

utility were a fixed, invariable quantity always

distinct from onerous utility, that is, utility

created by effort; but the two are constantly

intermingled and in inverse ratio. Man strives

ceaselessly to substitute the one for the other,

that is, to obtain, with the help of natural and

gratuitous utilities, the same results with less

effort. He makes wind, gravity, heat, gas do for

him what originally he accomplished only by

the strength of his own muscles.

Now, what happens? Although the result is the

same, the effort is less. Less effort implies less

service, and less service implies less value. All

progress, therefore, destroys some degree of

value, but how? Not at all by impairing the

usefulness of the result, but by substituting

gratuitous utility for onerous utility, natural

wealth for social wealth. From one point of

view, the part of value thus destroyed no longer

belongs in the field of political economy, since

it does not figure into our inventories; for it can

no longer be exchanged, i.e., bought or sold,

and humanity enjoys it without effort, almost

without being aware of it. It can no longer be

counted as relative wealth; it takes its place

among the blessings of God. But, on the other

hand, political economy would certainly be in

error in not taking account of it. To fail to do

so would be to lose sight of the essential, the

main consideration of all: the final outcome,

the useful result; it would be to misunderstand

the strongest forces working for sharing in

common and equality; it would be to see

everything in the social order except the

existing harmony. If this book is destined to

advance political economy a single step, it

will be through keeping constantly before the

reader's eyes that part of value which is

successively destroyed and then reclaimed in

the form of gratuitous utility for all humanity." [5]

What is so important to take home from this passage is that most people, especially those who clamor against income and wealth inequality, lose sight of these effects from gratuitous utility that have so prolific an enjoyment and benefits yet have easily taken them for granted in the grand scheme of things. It seems to be heavily conditioned into society that unemployment of certain classes of labor or tradesman due to innovations in capital investment or from international trade is inherently undesirable and that we need state intervention to ostensibly slow this process down via tariffs, subsidies and worker protections in union contracts. It's baffling to see the logical inconsistencies exhibited between people’s desires for these benefits at the individual vs. societal levels. You may often hear people decry automation, outsourcing of production, insourcing of labor, but have you ever heard anyone complain about not having to hand wash clothing or dishes, knit their own clothing, or see them scream at the checkout counter in a grocery store because of cheap produce?

The next chapter review will show more of the depths of man's desires, not just the logical mechanisms of how they are attained. Later reviews will expound upon the differences between value and utility and show where some of the classical economists, such as Adam Smith and Jean Baptiste Say, went wrong and gave fuel to the fire of the communists.

[1] Bastiat, Frederic. Economic Harmonies, p. 26, The Foundation for Economic Education, 1996; [2] Ibid, p. 30; [3] Ibid, p.28; [4] Ibid, p.27-28; [5]Ibid, p.32-33