Astroquotient - Part 1

What’s Your AQ?

Amateur astronomy is possibly the fastest growing pastime in the world. Telescopes and binoculars have never been so affordable. Affluent individuals can equip themselves as well as professionals, and a comparatively small financial investment is sufficient to provide today’s enthusiasts with scopes, cameras, computers and other paraphernalia of exceptional quality. Amateurs are now able to create astronomical photographs in their backyards that just a few decades ago would have been unimaginable outside of a professional observatory or university.

Amateur astronomers also continue to make significant contributions to the field through their discoveries. Countless comets, supernovae and asteroids have been discovered in recent years from private observatories created by amateurs in their back gardens. Many of these observatories are located in light-polluted suburbs on the outskirts of major cities, but such is the standard of modern equipment that this need no longer be a bar to achieving exceptional results. As far as amateur astronomy is concerned, the sky is the limit.

Today’s amateurs are also better informed and better connected than ever before. This is largely due to the Internet. Thanks to the digital revolution, amateur astronomers now have access to new types of equipment—CCD cameras, webcams, sophisticated processing software, etc—that the professional astronomers of thirty years ago could not have envisaged. It is no longer just the Universe that is expanding: the field of amateur astronomy is also rapidly expanding.

It is not surprising, therefore, that today’s amateur astronomer is a more ambitious animal than his counterpart of yesterday. With so much more to see and so much more to do, and so many more celestial objects within reach of amateur scopes, he is no longer satisfied to go out into the backyard, point a telescope in some random direction and simply have a gander. Today’s amateur structures his sessions : he sets himself ambitious targets : he meticulously records his observations : he expects to accumulate a growing list of achievements as the years roll by. (Ditto if he is a she!)

This raises an important question: by what yardstick should the contemporary amateur astronomer measure his progress in this increasingly competitive field? By what means can he indicate to his colleagues just how far up the long ladder he has currently climbed? I believe that amateur astronomy has suffered from the lack of a universal standard by which the experience and ability of its practitioners may be gauged. It was to address this problem that I came up with the concept of an astroquotient, or AQ.

Initially, I planned to put my ideas down on paper in book form. Astroquotient—that was my working title—was to be an observer’s manual, a handbook designed for the amateur astronomer. It would contain comprehensive lists of celestial objects suitable for amateur observation—enough, I hoped, to keep even the most enthusiastic amateur busy for years. Each celestial object would be assigned to one of five different levels depending on how difficult it was to observe. Certain criteria would have to be satisfied before an observer could claim to have properly observed a given object. But once he had successfully met these criteria, he would be assigned the starpoints associated with that object. The number of starpoints would depend on the level to which the object belonged. The easiest objects to observe (Level 1) would have the most starpoints associated with them, while the most difficult objects (Level 5) would have the fewest. This may seem a perverse way of arranging things, but I believed it was the best way of encouraging novices to begin with the easier well-known objects, before graduating to the more difficult arcane ones.

Finally there was to be a simple method of calculating how advanced or experienced an astronomer you were based on the history of your observations. It was this final element that gave the method its title. Your astroquotient, or AQ, would be a number between 0 and 200 which would tell you—and the rest of the world—how far you had advanced in the field of amateur astronomy. Just as your IQ, or Intelligence Quotient, supposedly reflected how intelligent you were, so your AQ would reflect how good an astronomer you were. Put simply, the value of your AQ would correlate to the total number of starpoints that you had currently accumulated. As the years passed, and you collected more and more starpoints, your AQ would nudge closer and closer to the magical figure of 200.

That was my initial plan. I quickly realized how useful it would be to set up an Astroquotient website to accompany the book, a website that would take care of all the details. Amateur astronomers from around the world could visit this site and create their own personal accounts. As an individual successfully observed more and more of the celestial objects on the various astroquotient lists, he would tick them off one by one on his account: the site would keep track of this progress and calculate the current value of his AQ. The honor system would apply.

That was the plan. The trouble was that I knew from the outset that it was a mere velleity—a pipe dream that I would never get around to realizing. I don’t have the web-skills to even know where to begin to create such a site, and I don’t have the patience or perseverence to sit down and write such a book. Mine is a mind that flits from one thing to another, easily becoming bored with a subject that just a few days before was an obsession. I did not have the aptitude to do this idea justice.

This is not to say that I simply gave up at the outset and never got any further than the basic concept. Initially I threw myself enthusiastically into the project, as is my wont, and convinced myself that if I stuck at it my labours would eventually bear fruit. I spent many months trawling through astronomical websites and books in search of lists of celestial objects to observe—Messier, Herschel 400, NGC, Burnham’s Celestial Handbook, etc. Before my enthusiasm began to wane, I had successfully compiled most of the data lists—variable stars, double and multiple stars, various classes of deep-sky objects, planets, asteroids, etc—and I had divided them up into five or six levels according to difficulty.

It was only when I began to set up spreadsheets to catalog these objects that I realized just how Herculean the task was that I had assigned myself. Recording even the J2000 coordinates of literally thousands of celestial objects was beyond me, not to mention all the other relevant data (eg stellar magnitudes and color indices, double-star separations and position angles, etc). A computer expert might have been able to find a way of automating much of this labour, but I was entering the data by hand, one item at a time. I estimated that it would take about a dozen years to complete if I worked at it steadily every day. My enthusiasm for the project quickly waned and the project stalled.

Nevertheless, I still think the idea of an astroquotient is a very good one, and it would be a shame to keep it all to myself. So I will do the next best thing: I will post all my data to Steemit and Microsoft OneDrive, and if there are any enterprising astronomers out there who agree with me that this is a good idea, but who do have the patience, the perseverance and the expertise to turn the idea into a working commodity, then they have my blessing to take this data and run with it for all they are worth.

Observing Criteria

In order to collect the starpoints for observing a particular celestial object, a number of criteria must be satisfied. These vary slightly depending on the category of the object, but there is one basic criterion that must be satisfied for all types of object: Positive ID.

Positive ID: Positive identification simply means that the object in question has been observed by the observer. This implies that an observation of a celestial object has been made by the observer, and the observer has satisfied himself that the object in question is indeed the target object.

Some research is inevitable if the observer is to be in a position to confirm that the object he has observed is the correct object. Astronomical data (celestial coordinates, magnitudes, color indices, etc) and helpful images are usually available in abundance on the Internet and in magazines, so little more need be said about what criteria the observer should use to establish Positive ID. I will merely add that common sense and honesty are the best guides. If you are satisfied that you have positively identified your target, then so am I. The honor system applies.

A word or two would not be out of place here concerning the methods used to make astronomical observations. Two methods of locating celestial objects are generally recognized by amateur astronomers: Manual Guiding and Device-Aided Guiding. Manual Guiding implies that the observer guides the telescope by hand, using his eyes to navigate to the target. Device-Aided Guiding implies that the telescope has been fitted with manual or digital setting circles, computer-aided devices or other automatic aids that can be used to automatically locate the target. Some astronomers may feel that the latter is cheating, but as far as I am concerned both methods are acceptable.

There are also two types of observation: Visual Observation and Image-Based Observation. Visual Observation refers to the live observation of a celestial object with the eye: this includes both naked-eye observations and observations made through the optics of a telescope or pair of binoculars. Image-Based Observation refers to the indirect observation of a celestial object through the use of astrophotography or CCD. In this case, the observer does not observe the object live, but sees an image of the object. This method allows the astronomer to capture images of objects too faint to be seen live through the scope.

Both of these techniques are acceptable methods of observation. In the case of Image-Based Observation, it is essential that the image be generated by the observer himself. It should not be necessary to point out that observing a celestial target in a magazine or on the Internet will not satisfy the observing criteria.

I will list the relevant observing criteria in a subsequent article. They will include things like the following:

- Estimating the magnitude of a variable star

- Estimating the separation of the two components of a double star

- Estimating the position angle of the two components of a double star

Amateur reports of such data are still of genuine value to the professional field, so you should record and post your observations. This is another area where an Astroquotient website could provide an invaluable service to the community. Perhaps the online posting of your observations should be one of the observing criteria that must be met before you are awarded the associated starpoints.

Calculating Your AQ

When I first came up with the idea of an astroquotient, I decided that an astronomer’s AQ would simply be twice the percentage of all available starpoints that he had currently amassed. For example: let’s say that the total number of starpoints on offer (T) is 1,000,000, and that our hypothetical amateur astronomer has currently amassed 625,320 starpoints (N). This is 62.532% of one million. Twice 62.532 is 125.064. Rounding down to the nearest integer gives us this particular astronomer’s current AQ: 125.

This simple formula insures that the resultant AQ will be an integer between 0 and 200 inclusive—a range that matches, more or less, the typical range of IQs. In the few years since I conceived of it, I have not had any reason to change this formula. But I am always open to new ideas.

Astropoints, Starpoints and Levels

At quite an early stage in the development process, I had already decided that the celestial objects in my lists should be divided into six classes, or levels, according to the difficulty they presented to the amateur astronomer. For example, observing Venus is much easier than observing Neptune, so if the former is a Level 1 observation, you would expect the latter to be, say, Level 3. By the time I had compiled my data sets, I realized that there were very few objects of Level 6, so I dumped them all into Level 5 and dropped Level 6 altogether.

I had also decided that the number of starpoints available for a Level 1 observation should be greater than the number for a Level 2 observation, and the number for a Level 2 observation should in turn be greater than the number for a Level 3 observation, and so on. This counterintuitive feature was designed to encourage astronomers to work their way through the lists systematically in order of difficulty, beginning with the easiest objects before tackling the harder ones.

But how many starpoints should be allocated to an object of Level 1 and how many to an object of Level 2, etc. I never really settled this matter to my satisfaction. I envisaged two possible approaches:

Assign appropriate numbers of starpoints to the different levels so that all the starpoints of Level 1 corresponded to 100 astropoints, all the starpoints of Level 2 corresponded to 50 astropoints, all the starpoints of Level 3 corresponded to 30 astropoints, all the starpoints of Level 4 corresponded to 15 astropoints, and all the starpoints of Level 5 corresponded to 5 astropoints. In other words, if you successfully observed all the Level 1 objects but none of the higher level objects, your AQ would be 100. If you then added all the Level 2 objects, your AQ would rise to 150. And so on. There was an obvious problem with this approach: you must first know how many objects there are in all five levels before you can work out how many starpoints each object must be allocated.

Alternatively, assign arbitrary starpoints to each level, irrespective of how many objects there are in that level. For example: Level 1 objects might earn one hundred starpoints each, Level 2 objects fifty starpoints, Level 3 twenty starpoints, Level 4 five starpoints, and Level 5 objects one starpoint each:

| Level | Starpoints Per Object |

|---|---|

| 1 | 100 |

| 2 | 50 |

| 3 | 20 |

| 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 1 |

The second of these two approaches is the simpler and my preferred option. But, once again, I am always open to new ideas.

In Part 2 I will begin to post my data lists. I have, however, already uploaded all the relevant files to Microsoft OneDrive, where they can be viewed and downloaded by anyone who is interested in this project. Just click on the following link:

The majority of these files are spreadsheets. For the first few years of the project, I did not have access to Microsoft Office’s Excel program, so the spreadsheets were created using Apache OpenOffice, with file extension .ods. Before the project stalled, however, I had upgraded my system, and subsequent spreadsheets were created using Excel, with file extension .xlsx.

Image Credits

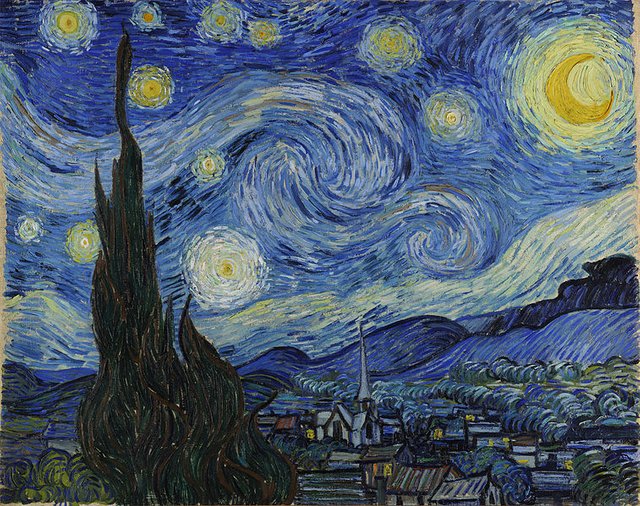

- Starry Night: Wikimedia Commons, Vincent Van Gogh, Museum of Modern Art (New York), Public Domain

- Galileo and the Doge of Venice: Wikimedia Commons, H J Detouche, Public Domain

This is amazing, but seem so intimidating lol. I've spent a good couple of years on a cheap telescope, just messing around getting to know how to use it but never really stuck at it for too long. I've ended up just reading up space stuff instead of exercising astronomy. What'd be best to revive something like this?

More importantly, what are your lowest-barrier recommendations to get started? I think this will be an interesting project (maybe the participation / interest volume isn't enough at the moment). But a good time to plan and test out posts that could work with the community. It'll take time, but man, that was an interesting read.

(i'll try to have another read at this again in the morning!)