Raging Against the Machines

Fears of technological displacement is nothing new to the modern world. In this piece, I continue reviewing the social and political upheaval of the Industrial Revolutions established in the previous pieces, Rethinking Artificial Intelligence and The Rise of the Machines Has Already Happened. In the latter, for example, I make the connection between Frankenstein and the Luddites.

The full essay, "Will Robots Want to Vote? An Investigation into the Implications of Artificial Intelligence for Liberty and Democracy," was written as part of a fellowship for The Fund for American Studies Robert Novak Journalism Program. For an introduction to the premise of the project, please read my speech, Will Robots Want to Vote? For an introductory summary to the final essay, please read, This will begin to make things right. The project is presented as a multi-part series. This is Part 3.

If you liked this post, please consider sharing, commenting, and upvoting. Thank you in advance. - Josh

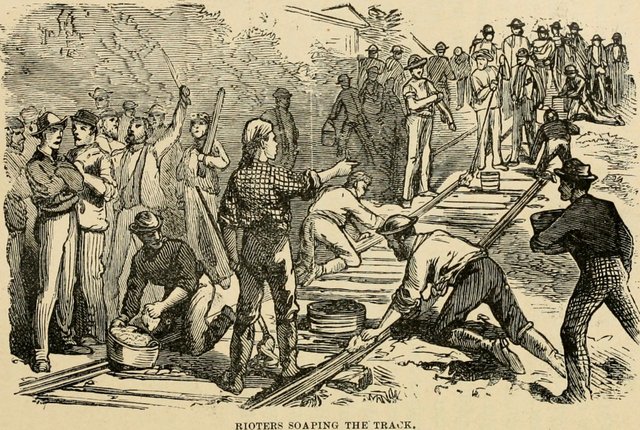

The Luddites

While the origin of the name of the Luddites is uncertain, their impact is undeniable. Calling someone a Luddite today is often a pejorative term implying that they are either technologically inept or that they reject technology altogether. But the members of the original Luddite movement, which began in 1811, were neither of these.

“Many were highly skilled machine operators in the textile industry,” wrote author Richard Conniff in a 2011 article for Smithsonian.com. Neither were the machines they attacked “particularly new," nor were the tactics they employed, he said.

“In truth, the secret of their enduring reputation depends less on what they did than on the name under which they did it. You could say that they were good at branding,” said Conniff.

Not only was machine-breaking criminalized in Britain in 1721, the 1812 Frame-Breaking Act made destroying mechanized looms punishable by death.

During the debate in the House of Lords before the law was passed, Lord Byron, the British poet and politician, gave a speech defending the protestors, whom who he said were merely responding to the economic hardships they faced because of the Napoleonic Wars. He also criticized the government’s use of the military to settle civil matters.

“The perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large and once honest and industrious body of the people into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community,” said Byron.

The Luddite movement culminated in a 5-year rebellion across the English countryside that was eventually quelled by government troops.

The Luddites were, however, only one group of machine-breakers at the time, nor were they the first to do so. French laborers also engaged in machine breaking as a prominent tactic during the French Revolution. But the motives of the two parties were not necessarily for the same reasons.

Jeff Horn, professor of history at Manhattan College, wrote in a 2003 essay for “The Proceedings of the Western Society for French History” that while machine-breaking in England was much more concerned withfocused on working conditions, the machine-breaking by the labor class in France could be tied to the revolutionary politics of the day.

French machine-breaking also took place against the backdrop of the Anglo-French Commercial Treaty of 1786, also called the Eden Agreement - a brief treaty between the British and French that lowered trade barriers on British textile and hardware imports into France and imported French wine into Britain.

While the French Revolution several years later ultimately caused the treaty to collapse, the treaty is considered a precursor to the revolution due to the economic anxiety in France over competition with British goods.

“In the context of the industrial recession caused by the Anglo-French Commercial Treaty of 1786, both economic elites and laboring classes shared deep misgivings about mechanization, particularly English-style textile machines then being constructed and diffused at record rates, and its effects on unemployment,” said Horn.

In the 1940s and the 1950s, Austrian economists F.A. Hayek and Ludwig von Mises criticized the view that the Industrial Revolution made workers’ lives miserable as an ideological argument advanced by Marxist academics.

In a 2001 article for the Foundation for Economic Education, American historian Thomas Woods, Jr., wrote that both Hayek and Mises viewed the complaints about working conditions during the 18th and 19th centuries as a sign that people were not only aware of their poverty, but were able to raise their standard of living by working in factories, which represented the best opportunity for them to survive at the time.

Labor

While the rise of the labor movement is generally associated with the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, as well as its ties to communism during the Cold War, its roots in America go back to some of the earliest days of European colonization in the New World. Protests over wages and working conditions did not begin with the advent of mechanization and mass production.

The first recorded labor strike in North America, for example, occurred in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. Polish craftsmen leveraged their economic importance to the colony by going on strike in order to secure the right to vote.

Other strikes that took place in the Thirteen Colonies during the 17th century included the Indentured Servants’ and Fisherman’s Mutiny of 1636 in Maine; the Indentured Servants’ Plot of 1661 in Virginia; and the New York City Carters’ Strike of 1677 and 1684, just to name a few.

Slave revolts also long predate major advancements in technology and industrialization, such as the slave uprisings of the Roman Republic, and carried into slave rebellions in the early days of the Thirteen Colonies as well.

The first national labor federation formed in the United States was the short-lived National Labor Union in 1866 to call on Congress to enact labor reforms, such as the eight-hour work day, through legislation. In 1886, the American Federation of Labor (AFL), a predecessor to the AFL-CIO, formed.

The AFL endorsed Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryant in 1908. In 1912, a bipartisan Congress and Republican President William H. Taft elevated the Department of Labor to the cabinet level; its predecessors were previously had been nested as agencies inside of the Department of the Interior and then the Department of Commerce and Labor. Democratic President Woodrow Wilson appointed the first labor secretary, William B. Wilson of the United Mine Workers of America, in 1913.

Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt proposed the New Deal to Congress 20 years later amid the Great Depression, earning the support of the AFL and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) which would help FDR win a second term. The CIO would then go on to form a political action committee to help FDR win reelection for to a third term. In 1962, Democratic President John F. Kennedy signed an executive order giving federal workers the right to collective bargaining.

In January of this year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that union membership for 2016 had declined by 240,000 from the previous year to 14.6 million strong, or 10.7 percent of the workforce, almost half of what it had been more than three decades earlier.

In 1983, the first year for which comparable union data is available, the union membership rate was 20.1 percent, and there were 17.7 million union workers.

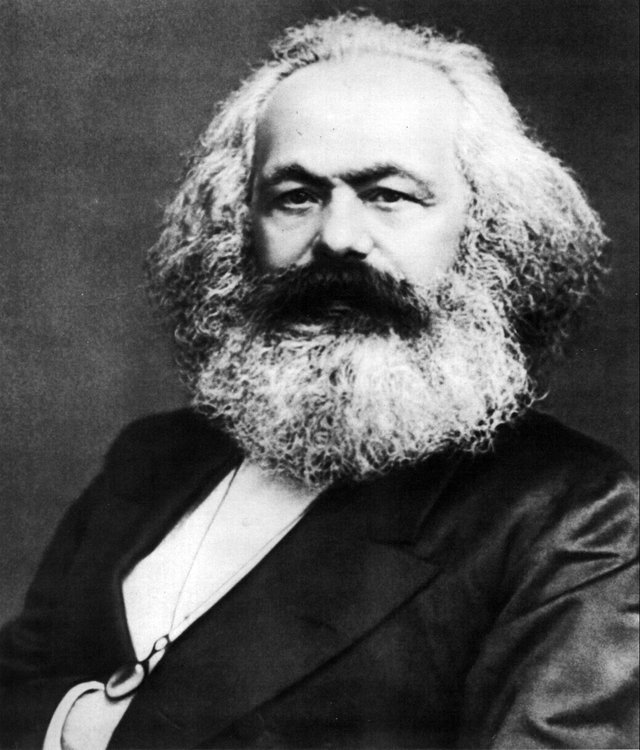

Marx

The 19th century philosopher and father of communism, Karl Marx, reacted to the Industrial Revolution in his work, Das Kapital, articulating a competition he perceived between the machine and the worker. But Marx criticized the Luddites for misdirecting their energies into destroying machines, which he said was what invited the violent reactions against their movement.

“It took both time and experience before the workpeople learnt to distinguish between machinery and its employment by capital, and to direct their attacks, not against the material instruments of production, but against the modes in which they are used,” wrote Marx.

But in a 1952 lecture entitled, “Individualism and the Industrial Revolution,” Mises critiqued Marx’s view of capitalist exploitation, noting that Great Britain experienced a population explosion during the first half of the 18th century that made the old economic system unsustainable. It was the capitalist push to liberalize commerce and employ the poor, he argued, that enabled many more people to survive than would have under the old system.

“You can’t compare the United States with England. The United States began almost as a country of modern capitalism. But we may say by and large that out of eight people living today in the countries of Western civilization, seven are alive only because of the Industrial Revolution,” said Mises.

The foundations of the Industrial Revolution are built upon the discoveries of the Scientific Revolution that preceded it, particularly those of Sir Isaac Newton, whose observations of the motion of the natural world form the very basis of the mechanical laws needed to successfully build the machines that would facilitate much of the prosperity and suffering of the last century.

Newton teaches us about bodies in motion or at rest and the forces that act upon them, particularly the symmetry of action and reaction. While it is popular these days to place the blame of society’s ills at the feet of either capitalism or socialism, neither economic system operates in a vacuum. The great political conflicts, economic innovations, and humanitarian triumphs of the past several hundred years are the expression of a complex dance between the adherents of the ideals of the two systems, as well as the people caught in the middle.

Fears of technological unemployment have persisted since the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, but our society continues to adapt through a dynamic interplay between innovation, competition, regulation, and the creation of new markets.

Thank you for reading,

- Josh

Further Reading

- "Future of Work: The Future of Work Can Be Explained by Oregon Loggers." Quartz. Accessed October 26, 2017. https://qz.com/se/what-happens-next/1106924/automation-could-destroy-jobs-but-make-workers-safer/.

- Alloway, Tracy. "Saudi Arabia Gives Citizenship to a Robot." Bloomberg. October 26, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-26/saudi-arabia-gives-citizenship-to-a-robot-claims-global-first

- Collins, Keith. "This new Twitter account hunts for bots that push political opinions." Quartz. October 25, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://qz.com/1110481/this-new-twitter-account-hunts-for-bots-that-push-political-opinions/.

- Drum. Kevin. "The AI Revolution Is Coming—And It Will Take Your Job Sooner Than You Think." Mother Jones. October 26, 2017. Accessed 27, 2017. http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2017/10/you-will-lose-your-job-to-a-robot-and-sooner-than-you-think-2/

- Gershgorn, Dave. "If the US government can’t explain AI’s decisions it shouldn’t use it." Quartz. October 23, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://qz.com/1109438/google-and-microsoft-ai-researchers-say-us-government-shouldnt-use-artificial-intelligence-if-it-cant-explain-decisions/.

- Huang, Echo. "After firing workers in the US, Tesla is recruiting in China." Quartz. October 25, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://qz.com/1111329/after-laying-off-workers-in-the-us-tesla-tsla-is-recruiting-in-china/.

- Kline, Daniel B. "Steve Wozniak Does Not Share Elon Musk's Dire View of AI." October 25, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technology/steve-wozniak-does-not-share-elon-musks-dire-view-of-ai/ar-AAu2dq1

Related Posts by Josh Peterson

- "The Rise of the Machines Has Already Happened." Steemit. October 25, 2017. Accessed October 27, 2017. https://steemit.com/artificial-intelligence/@joshpeterson/the-rise-of-the-machines-as-a-historical-metaphor

- "Rethinking Artificial Intelligence." Steemit. October 22, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2017. https://steemit.com/artificial-intelligence/@joshpeterson/rethinking-artificial-intelligence

- "This will begin to make things right." Steemit. October 22, 2017. Accessed October 22, 2017. https://steemit.com/writing/@joshpeterson/this-will-begin-to-make-things-right.

- "Will Robots Want to Vote?" Steemit. October 19, 2017. Accessed October 22, 2017. https://steemit.com/artificial-intelligence/@joshpeterson/will-robots-want-to-vote.

View Post History

@originalworks

The @OriginalWorks bot has determined this post by @joshpeterson to be original material and upvoted(2%) it!

To call @OriginalWorks, simply reply to any post with @originalworks or !originalworks in your message!

This post has received a 3.13 % upvote from @drotto thanks to: @banjo.