Retrospective: Ghost in the Shell (1995)

When I first watched Ghost in the Shell, I was impressed by the fluid animations, the detailed visuals, the melancholic atmosphere and the slick action scenes. A dozen years later, after watching it again, I picked up the finer points my teenage self didn't: the post-cyberpunk ethos, the characterisation, the tight storytelling, and most of all, the reversal of emphasis on philosophy and action.

When put together, Ghost in the Shell is a philosophy film disguised as a sci fi thriller.

(Spoilers ahead!)

Post-Cyberpunk, NOT Cyberpunk

It has often been claimed that Ghost in the Shell is a cyberpunk franchise. It's more accurately described as post-cyberpunk. Major Kusanagi Motoko and her colleagues at Section 9 are members of a secret police agency. Their job is to uphold the current order. They may face corrupt government officials, terrorists and cybercriminals, but they act under the colour of the law -- even if the government cannot officially sanction their deeds.

Cyberpunk stories depict amoral, nihilistic underworlds populated by unscrupulous hackers, slick corporate representatives, hardboiled cops, well-heeled businessmen. Cyberpunk media such as William Gibson's Neuromancer, Neil Stephenson's Snow Crash or the Cyberpunk 2020 tabletop role-playing games, emphasise the punk of cyberpunk. They focus on high tech and low life, powerful megacorporations and corrupt governments, and the people caught in the games of power and wealth. Cyberpunk is about how money and politics and technology conspire to degrade the human soul -- and how people scrape out a living at the ragged edge of an increasingly dystopian society while trying to retain their sense of self.

Ghost in the Shell sets itself apart by making its protagonists members of a secret police organisation. This allows the protagonists to come into contact with the coterie of cybercrime archetypes, but it also charges the protagonists with upholding civilisation instead of eroding it. By being government agents, they will naturally have access to state-of-the-art tech and training, letting them plausibly have an edge over their adversaries, while giving them multiple opportunities to encounter black market tech. They see at first hand how predators use technology to hollow out the human spirit -- but instead of dirtying their hands, they take a stand against it.

Post-cyberpunk contrasts those who use technology to uphold civilisation against those who abuse it for their own ends. The characters of Ghost in the Shell inhabit a world filled with corruption and dirty politics, but Section 9 still tries to serve and protect the people. Unlike traditional cyberpunk works that shows how technology dehumanises people, Ghost in the Shell aims to examine whether technology can elevate humanity, and the cost of doing so.

Merging Character and Plot

In the original manga, Kusanagi was a vivacious woman who enjoyed practical jokes, had a casual approach to romance and violence, and had a wide range of emotional affect. Batou was a support character who played the role of comic relief, but otherwise sank into the background until the focus was no longer on Kusanagi.

The anime radically changed the characters. Kusanagi was now serious and focused. She rarely shows emotions, but when she does it emphasises the gravity of a scene. Instead of sticking her tongue at people behind their backs, she is more likely to exchange philosophical argument. Batou, in turn, was promoted to the role of her unofficial second-in-command, assisting her during key scenes and also voicing deep thoughts of his own. Now he is both a shooter and a thinker, able to match Kusanagi and drive both the action and the dialogue.

This character shift elevates the anime above the manga. Manga Section 9 comes off as a unit of cowboys just a few steps away from being loose cannons, who have no qualms turning their skills on their allies and superiors on a whim, and only slightly more skilled than the criminals they face. Anime Section 9 is an elite group of operators who take the time to ponder their humanity.

The anime characters created a somber, introspective atmosphere lacking in the manga, conforming with the anime's philosophical core. With Anime Kusanagi and Anime Batou portrayed as intellectual cyborg shooters, it now makes sense for them to contemplate their navels when they're not chasing bad guys. This, in turn, makes the ending believable.

In the manga, the Puppet Master abruptly launches into a pages-long exposition on life and transmission of information. It is a jarring departure from a manga otherwise filled with gunfire and cyberwarfare but little explicit discussion of higher concepts. In the anime, the exposition is reduced to a minimum -- and since the characters are already established as deep thinkers who also act decisively, the concluding scene fits with the overall tone and direction of the anime.

The manga characters were action-oriented; the reader either had to tease out philosophy from the plot, or the mangaka had to break up the action to make the themes and philosophy explicit. The anime characters give voice to the philosophy explored in the franchise, showcasing their characters and explicitly drawing out the ideas the filmmaker is exploring. The latter approach makes the philosophy more accessible and digestible to the audience -- and in doing so, raised Ghost in the Shell above other sci fi stories that merely used cybertech as stage dressing.

Lean Storytelling

Ghost in the Shell does more in 82 minutes than what other films try to accomplish in over 2 hours. The anime achieves this through a minimalist cast and efficient storytelling.

The only extraneous scene takes place in the middle of the film, showcasing daily life in 2029 Tokyo. Otherwise, every sequence is tightly plotted, with ramifications down the line. Of great importance is the use of technology: every key bit of technology is used at least twice, first to introduce the audience to the tech, and then to facilitate the plot.

The opening scene has Kusanagi using thermoptic camouflage to assassinate a bad guy. It's an iconic moment that defines the franchise, introducing the tech and the murky politics of the world. Later, while preparing for a mission, Kusanagi tells Togusa that she brought him aboard Section 9 because he has the least amount of cybernetic enhancements and Kusanagi values his different perspective. During that mission, their target uses thermoptic camouflage to evade pursuit, suggesting that the antagonists also have access to such tech, and showing that such camouflage can defeat Section 9's sensors. When the Puppet Master appears, thermoptic camouflage plays a critical role in aiding the antagonists' plans, and this allows Togusa to demonstrate his out-of-the-box thinking to detect the invisible intruders, enabling the final showdown later on.

In the movie, technology drives the plot and characterisation. We see this again in the use of high velocity rounds. During the chase scene, the target loads his submachine gun with high velocity rounds to disable Section 9's truck. Batou later comments on how the ammunition damaged the weapon's internals. Later, Kusanagi employs HV ammo against a spider tank, but takes the trouble to swap out the barrel of her rifle -- and even so, the HV rounds don't do squat.

The chase scene sets up the existence of HV ammunition and its limitations. This prepares the viewer for Kusanagi using them later and sets up the expectation that the HV rounds would tear the tank apart. Her taking the time to swap out her weapon parts solidifies her characterisation as an operator. When the HV bullets bounce off the tank, it undermines the viewers' expectations and justifies the following scene which has her try to hack the tank's cyberbrain, in the process ripping off most of her limbs. This in turn makes the climax possible, showing why she can't simply evade the snipers targeting her, and ratchets up the tension further.

By compressing technology, characterisation and plot into as few scenes as possible, the director made the philosophy scenes work. When discussing the philosophy and implications of technology in the work, the characters don't stand around and exchange lines in a context-free vacuum. They always talk philosophy in transitional scenes.

In these scenes, the characters are either on the way to somewhere or waiting for something to happen. One exchange takes place while Kusanagi and Togusa are on the road, preparing for a mission; another takes place on a boat when Kusanagi and Batou are off-duty and awaiting orders; a third is inside an elevator as Section 9 prepares to head out.

In other movies, these scenes would be short takes, empty of beats. Here, the director used the opportunity to fill the gap by delving into matters related to prior scenes, making the philosophy feel organic instead of being forced on the audience. It also eliminates the need to have separate talky scenes dedicated solely to philosophy.

Ghost in the Shell is an exemplar of lean storytelling and a masterclass in the craft of maximising the efficiency of every scene.

Reversing Action and Philosophy

In most movies, action scenes are the highlight of the film. Scenes in between the action are crafted to lead up to the combat.

Ghost in the Shell reverses this logic: the action scenes lead to the philosophy.

Conventional films feature lengthy action sequences featuring kinetic gun battles, furious hand-to-hand combat and waves of mooks, creating spectacles that hook the audience and keep them watching. The payoff of the film is watching the protagonist overcome the antagonist through wit or violence (or both), saving the day and winning the girl. Any deep thought is incidental.

Ghost in the Shell, by contrast, treats action scenes differently, with long periods of building-up and short bursts of overwhelming violence. The action scenes are much shorter and feature a far lower body count than conventional action films, because they do not exist to create spectacle, but to set up the scenes where characters ponder their humanity and their place in the world. The assassination in the beginning reveal the political system of future Japan and sets the stage for the rest of the plot; the chase scene later on reveals the possibility of false memories, in turn leading to Batou and Kusanagi musing on what makes them human; the final showdown creates the setting for the actual denouement.

Unlike traditional movie logic, the true antagonists of Ghost in the Shell aren't directly dealt with. Indeed, at the end Batou describes the resolution as a 'stalemate'. This wouldn't work in a film that places spectacle first: audiences would expect nothing less than total victory after experiencing one action extravaganza after another that consistently raises the emotional tenor and stakes of the story. However, in a story that places philosophy first, underscored by an introspective atmosphere, it is appropriate: the true resolution lies with the merging of the Puppet Master and Kusanagi to create a higher life form. It is the ultimate payoff for an audience already primed for a movie that promises to explore transcendental matters in the guise of sci-fi action. The stalemate is an afterthought, but it fits into the overall cyberpunk culture, in which there are no major lasting victories, just personal successes at the individual level.

Philosophy with a Dash of Action

In an industry defined by visuals and spectacle, Ghost in the Shell dares to do something different. While it employs a high standard of visual quality, instead of relying on the Hollywood standbys of intense action scenes, Ghost in the Shell delivered philosophy with a dash of action. It made full use of its sci fi mileu, setting up scenarios that organically explore the implications of these technologies and characters who combine combat skills with intellect.

Lesser filmmakers would have stumbled, either by making the philosophy ultra-abstract and the action scenes boring, or by concentrating on action and neglecting deep thought. Ghost in the Shell finds the perfect balance between the two, cementing its position as a masterpiece.

--

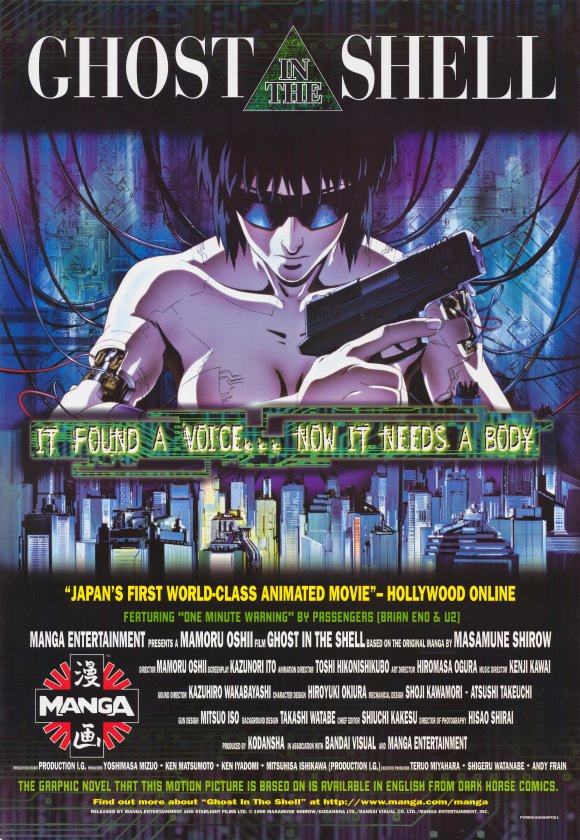

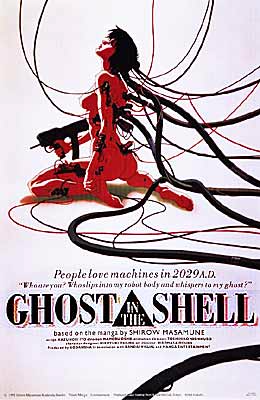

All images from Ghost in the Shell (1996) and publicity materials.

I suspect failing to understand this, rather than the alleged "whitewashing," is what will lead to the cinematic flop of 2017.

You got that right. If Rotten Tomatoes is any indication, the 2017 version is just another generic sci fi movie that focuses on action spectacles and mishandles philosophy.

Very nice post about of of the great anime works!

And look at this from the first picture:

"Japans first World-Class animated movie" - Hollywood online.

That tells you more about Hollywood online then about Japans animated movies. Not to mention series.

(Did anyone mention Robotech btw? You know where the US "stole" the Japanese series Macross. FunFact: The Macross movie lead was the same voice in the English version too.)

Thanks!

I'm not familiar with Robotech, I'm afraid. Haven't seen any mention of Robotech in my research.

But, yes, that comment from Hollywood Online is telling. As I understand it, anime and manga from the 80s still compare favourably to their contemporaries.

I don't have much knowledge about the 80s, but if you say 80s there definitely is Akira 1988.

Washington post said it was "An example for the future of animation".