Pioneers of Astronomy: Tycho Brahe

PIONEERS OF ASTRONOMY: TYCHO BRAHE

(Image from researchthetopic.wikispaces.com)

Perhaps the first person to dedicate his life to astronomy was Tycho Brahe. He built his own observatory and had many sophisticated instruments built. He also produced maps of the heavens that were more accurate than anything that had come before, and was witness to astronomical events that shattered the idea of the fixed stars and crystal spheres. However, he was certainly not a scientist. Tycho Brahe firmly believed in a mythical interpretation of the heavens and was thoroughly opposed to the Copernican model. He was very much a transitional figure between the Ptolemaic Mystics and the Galilean scientists.

CHILDHOOD

His status as a transitional figure is even reflected in his name, since he chose to Latinise his first name but not his last. Born in Knudstrup, Scandinavia on 14 December 1546, Tyge Brahe’s life was already predestined to follow a path straight out of a Robert Louis Stevenson adventure. His was an aristocratic family. His father, Otto, served the King as a privy councillor and ended his career as governor of Helsingborg Castle. Otto had a brother called Joergan who was an admiral in the Danish Navy. Joergan was married but without children and there had been an agreement between the brothers that Otto would hand over his eldest son for Joergan to raise as his own. However, when Joergan arrived to claim Tyge as his own as per the deal, Otto proved unwilling to go through with it. But Tyge only remained with his natural father for a year, because after his brother was born he was kidnapped by his uncle and taken to live with him in Torstrup.

As a child, Tycho (as we shall now call him) was taught Latin and joined the university of Copenhagen in April 1559. He was thirteen at the time, which to modern eyes seems a rather tender age to be starting higher education. But in the sixteenth century it was quite normal for a teenager to go to university so that he might be shaped to fit some pre-existing role in Church or State befitting his station. But if his elders expected Tycho would follow in his father’s footsteps and dedicate his life to the service of the King, their plans were changed by the heavens themselves. On 21st August 1560, Tycho witnessed a partial eclipse of the Sun. In itself that must have left its mark, but Tycho was more impressed by the fact that ancient charts had predicted such an event would take place. This realisation effectively mapped out Tycho’s career for him, and he focused his mind on astronomy and math, buying a copy of Ptolemy’s work on 30th November 1560.

CHOOSING THE LIFE OF AN ASTRONOMER

(Image from pinterest.com)

How did his family react to this change of career? Well, they certainly did not approve of it, since astronomy was not a fitting pursuit for a person of Tycho’s standing. So, when he left Denmark in February 1562 to complete his education abroad (also common practice) he was accompanied by Anderson Vengel, who was four years his senior and under instructions from Joergan to keep an eye on what Tycho was up to. On March 24 1562, they both enrolled at the university of Leipzig where Tycho was officially studying law. But while he made some effort to pursue the career that had been chosen for him, he spent far more of his time on astronomy, studying the heavens after Vengel had retired to bed and spending any spare cash he had on astronomical books and instruments.

But, as Tycho’s skills developed he became less impressed with the accuracy of ancient charts. The most accurate prediction had missed the mark by several days. Tycho took it upon himself to produce more accurate tables. This was easier said than done. It would take many decades of painstaking work, a challenge that was compounded by the ineffectual tools that required great skill to use. Tycho would need to produce more accurate equipment and a family tragedy provided the money to do this. On May of 1565, war broke out between Sweden and Denmark and Tycho was ordered home by his uncle. When King Friedrich II fell into a river while crossing a bridge, Joergan was one of those who jumped in to rescue him. Although the Monarch escaped unharmed, Joergan developed a chill and died on 21st June 1565 from the complications that resulted. Tycho inherited money and although his family did not approve, there was little they could do prevent this financially secure individual from chasing his career. In 1566, Tycho set off on travels, eventually ending up at the University of Rostock where he studied alchemy, medicine, and astronomy.

THE PROPHETIC ECLIPSE

Then, on 28th October 1566, a celestial event occurred that greatly improved Tycho’s reputation. Following an eclipse of the moon, he drew up astrological charts that claimed the event heralded the death of the Ottoman sultan, Salaiman the Magnificant. The sultan’s empire was a threat to Christian parts of Europe so when news of his actual death was received it was with no small relief and Tycho’s reputation as an astrologer soared. However, it later transpired that the Sultan had died weeks before the eclipse. This obviously took the shine off of Tycho’s predictions and it may have cost him more than that. At 7PM on 29th December 1566, Tycho was engaged in a duel with a Danish aristocrat called Manderup Parsberg. This was the culmination of an argument that had begun at a dance they both attended. The actual content of the argument is no longer known. Some say they argued over who was the better mathematician, while others speculate that Parsberg mocked Tycho for predicting the death of a sultan who had already passed away. Whatever the reason, they bumped into each other on several occasions and the row escalated until only a fight with swords would settle it. Tycho ended up losing part of his nose and ever afterward wore a prosthetic fashioned from gold and silver.

Yet another celestial event would occur on 11th November 1572 and provide Tycho with a staggering revelation. But before that, several important but more personal events occurred. One such event would give Tycho the financial wherewithal to continue his observations, which were placing an increasing pressure to upgrade the instruments at his disposal. On May 14th 1568, Tycho received a promise from King Friedrich II that he would have the next Canonry to become vacant at the Cathedral of Roskilde in Seeland. Although this sounds more like a job offer for an aspiring bishop than an astrologer, in Protestant Denmark the position of Canonry was granted to men of learning who the King thought showed promise. It provided Tycho with a secure future.

Tycho spent much of 1568 travelling, before settling down in Augsburg in 1569. Here, in order to aid his calculations of the movement of the planets, he had a huge quadrant built. Its radius was six meters and it stood on a hill in a friend’s garden until a storm destroyed it in December 1574. Three years previously, Tycho had returned to Denmark upon receiving news that his natural father was gravely ill. Otto Brae died on 9th May 1571, leaving his main properties at Knudstrup to Tycho and his brother, Steen.

THE NEW STAR

(Image from commons.wikimedia.org)

While these events were important to Tycho personally, what he witnessed on 11th November 1572 was important for the development of the Tycho of scientific culture. It was on that night that he noticed there was a new star, shining as bright as Venus, in the constellation known as Cassiopeia. Today, we know that this star was actually a supernova, which is an event in which a star dramatically ends its life in an enormous explosion bright enough to outshine 100 billion Suns. But the idea of the fixed stars coming to an end end was considered absurd in the 16th century. Rather, the stars were considered to be eternal, their numbers remaining constant for all time. With that in mind, it can clearly be seen just what kind of impact the appearance of a new star would have had on astrologers like Tycho. He set to work finding the answers to the two important questions that arose following this dramatic event. The first question was a task for what we would call astronomy, which was to determine if this really was a star. To find out for sure, Tycho had to measure the position of this object relative to the fixed stars to see if it moved. If he did notice a shift, then that would rule out the possibility that this was a star, and more likely a local phenomena like a comet. But during the 18 months it was visible, Tycho could detect no apparent movement and concluded that it must be a star. He published his findings in a book called ‘De Stella Nova’ or ‘The New Star’, which is where the term nova is derived from.

Tycho also had to determine what the astrological significance of the star was. Actually, Europe was in such turmoil at the time that there was no shortage of events to read astrological significance into. The Catholic Church was fighting back after the Reformation, the French wars of religion were taking place and there were battles in the Netherlands between independence fighters fighters and the Spanish. Today, astronomy and astrology are quite separate disciplines (and it’s fair to say that the former has no time for the latter) but in Tycho’s day there was no distinction between the two. With that in mind, it’s interesting to note that the conclusions Tycho came to about the heavens following the emergence of the star were simultaneously pre- and post-Ptolemaic. Clearly, the appearance of the new star radically changed the mystic’s view of the eternal nature of the fixed stars. But equally, while observing the new star for signs of a change in position, Tycho also obtained the most precise data of the time that showed no sign of parallax and this was enough reason (in his eyes) to dismiss Copernican ideas of an Earth in motion.

Today the star is often referred to as ‘Tycho’s star’ or ‘Tycho’s supernova’. Although this shows that the star’s appearance was pivotal moment in the development of the Tycho of scientific legend, there is little evidence that he was much affected by it on a personal level. But something that was important to him on that level occurred in 1573 when Tycho met his future wife Christine (also known as Kirstine). Actually, they never went through with a proper wedding ceremony (which may be because Christine was a commoner) but this was not a requirement in 16th century Denmark and a pair were considered man and wife if they lived together for more than three years. By 1574, Tycho’s reputation as an expert astronomer had grown to the point where he was asked to give lectures and his very presence in the country was considered to add to its prestige. The trouble was, Tycho was very often out of the country, a fact he put down to his distaste of the way things were run in Denmark. He had plans to move to Basle around 1575 and this prompted King Frederick II to dangle various gifts in front of him as an incentive to stay. Tycho was first offered the gift of a castle but this was turned down, probably because the administrative duties that went with it were off-putting. Undeterred, the King then offered the astronomer a small island, plus an income and the promise to pay for the construction of a house. Tycho accepted this offer.

THE ISLAND OF HVEEN

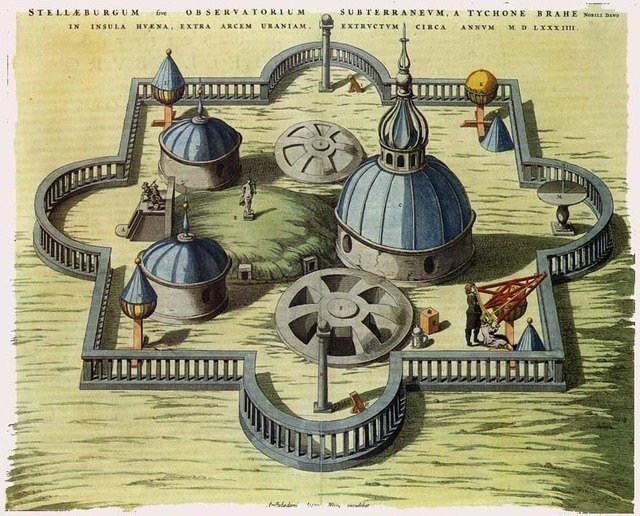

(Image from commons.wikimedia.org)

The island itself was called Hveen and was situated between Copenhagen and Elsinore. It was oblong in shape and at its highest point was only 160 feet above sea level. It was here that Tycho had his home cum observatory built. In what may seem a fitting reflection of Tycho’s position as a transitional figure between mysticism and science, the observatory was built with both disciplines in mind. Called Uraniborg after Urania the muse of astronomy, it was filled with the best instruments of the day and eventually even included its own printing press. The mystical side of Tycho’s psyche was reflected in the way the structure of the heavens. The observatory would attract many learned men, but as for Tycho himself, he spent most of his time continuing the work he had begun when aged 16: providing an accurate map of the planets’ movements. Even with much-improved instruments, the task was arduous and he would not live to finish it. It did, however, allow him to disprove the notion of the crystal spheres, an achievement aided by the arrival of a comet that he first noticed on 13 November 1577. Armed with his accurate observations, Tycho was able to show that the comet’s path cut right through the places where the crystal spheres were reckoned to be. Other astronomers reached the same conclusion, but Tycho’s observations were known to be the most accurate.

TYCHO’S RADICAL IDEAS

Tycho wrote a major book, published in two volumes in 1587 and 1588, that described his model of the universe. Drawing in his observations of the new star and the comet, ‘Astronomiae Instaurate Progymasmata’ (‘Introduction to the New Astronomy’) was a kind of halfway house between the Ptolemaic and Copernican models. Tycho was able to do away with epicycles and deferents by displacing the centre of the planetary orbits from Earth and was probably the first person to suggest that the planets were suspended in empty space. This latter point was a very modern way of thinking about the Universe, but Tycho was more of the Ptolemaic school in the way that he insisted the Earth did not move. Actually, at that time the Catholic Church was yet to turn against Copernicism, the Protestant church definitely had. An astronomer like Tycho depended on the patronage of the King and it would have been career suicide to promote the Copernican model. But don’t let that fact that lead you to believe that Tycho’s hand was somehow forced, because he truly believed that the earth did not move.

But the important point was that Tycho’s lifestyle could only exist for as long as the King permitted it. Although he was a world-class astronomer, he was also a bit of a liability. He was often rude to guests that he didn’t like, he flouted protocol by giving his low-born wife a place of honour at dinners and he neglected his duties as Lord of the Manor abysmally. He had also developed rather expensive tastes and his observatory was lavishly expensive to run. This lifestyle seems to have been tolerated by King Friedrick II but then he died in 1588. His successor was his son, Christian. He was only eleven at the time and would not be crowned until he reached the age of twenty in 1560. Before he did reach that age, Danish nobles elected four of their number to act as Protectors, and it was business as usual for Tycho: Mapping the heavens, entertaining distinguished guests, upsetting some with his brusque manner, running up debts (that the State paid off) and neglecting his other duties.

PARTY’S OVER

When King Christian IV was crowned, one of his first actions was to tighten the economy. Not surprisingly, Tycho’s expensive lifestyle caught his attention and he cut the amount of money going to the observatory. The King’s attitude was probably that Uraniborg was up and running and could run just as well on a reduced budget, but Tycho reacted to this in a way reminiscent of a spoils child. If he couldn’t run the observatory in the way to which he was accustomed, he wouldn’t bother to run it at all. And that wasn’t the only way in which the new King slashed Tycho’s income, because he withdrew his annual pension in March 1597. Tycho was still a wealthy individual despite this, but he took it as a slight and he left the island of Hveen in April that year. While on his travels, it appears the astronomer had second thoughts, and he wrote what he may have considered to be a letter of apology to the King, offering to return to Denmark. But his letter was unfortunately worded in a way that offended the King, since Tycho addressed him as an equal and seemed to imply that he would refuse a royal request. Whether this latter point was merely a case of unfortunate grammar or not, Tycho had effectively locked himself out of Denmark.

ENTER THE SUCCESSOR

Which is a good point to end the story of the mutilated-nosed mystic/scientific astronomer. Aged fifty by now, he would not contribute anything of great significance before his death, which was soon to come. And yet, his life’s work was unfinished and it was essential that a worthy individual would continue his legacy. That man proved to be one Johannes Kepler...

@extie-dasilva

glad we are getting some astronomy here. Great and thorough work. fully up'ed

Amazing reflection on one heck of a man! I see you left out some of the more bizarre anecdotes, but fair enough. :)

I consider Tycho Brahe to be the coolest person to have ever lived. (scroll down to the comments)

I need an upvote to my steemit post. This is the link: https://steemit.com/steemit/@collin22000/how-to-make-your-child-smarter