Applying Game Theory to Literature and Life

Game theory is the study of strategic, goal-oriented decision-making. Game theorists, like famed mathematician John Nash, attempt to construct mathematical models of conflict and cooperation between rational decision-makers. Initially, the goal was to make conjectures about economic trends, and try to interpret the behavior of markets and consumers. Antoine Augustin Cournot introduced game-theory as we know it in 1838 when he published his "Cournot Duopoly," an economic model describing any industry structure in which companies compete in terms of output. Since then, the applications have proliferated significantly.

Scientists now apply game-theory strategies in almost every discipline: biology, ethics, sociology, physics, political science, and even literature. The reason for this surge is game-theory's nearly universal applicability. Even when considering subatomic particles or ant colonies, where we don't normally expect to find rational decision-making, the tenets of game-theory can still be applied. While we may not be able to predict the precise decisions of an individual ant (not yet, anyway), through game-theory we can make educated guesses about how the population as a whole is likely to behave. Human societies are considered in much the same manner, but our behavior is far more complex. Our various goals and strategies are diverse and often hopelessly entangled. Each of us pursues subjectively constructed goals, which form games in and of themselves. Relationships, college courses, military service-- anything with a goal can be thought of as a game. Life's scoreboard then, is our own private tally of wins and losses, our subjective perception of collective success or failure.

We are often told that we learn from our failures. This is certainly true, but we do not learn merely from the outcome. We also learn from the strategy that led us there. This truth is evident in both literary and dramatic fiction, where imaginary games are played out on a grand scale. In almost every narrative, there is a protagonist—a player—trying to attain some goal. Hamlet, for example, wants to avenge the murder of his father, Oedipus the King wants to find the truth, William Wallace wants to free Scotland, Harry Potter wants to defeat Voldemort, and so on to infinity. The goal of the protagonist forms the game. The rules are provided by the circumstances of plot and the limits of language. Each character is a player, and the protagonist must have a strategy for achieving their goal. Their strategy is the essential part of their character. Their strategy will inform the entire structure and meaning of the narrative.

It is a logical necessity that a player's strategy be either perfect or imperfect. If their strategy appears to be perfect, we assume they will win the game. Take the majority of Hollywood movies, for example. Our heroes are so strong-willed, courageous, and physically powerful that we are often assured of their victory before we even reach the theater. In the better movies, novels, and plays, the strategy of the protagonist is at least slightly flawed, and we as an audience are cued into these flaws in order to create tension. Johnny is an alcoholic trying to win a custody battle. Carl wants to save his marriage, but he can't stop cheating on his wife. Oedipus wants to rid Thebes of a curse, but he himself has brought the curse upon Thebes. Ultimately, the adaptability of these protagonists will determine their fate. If they cannot correct their strategy, the story will presumably end in tragedy. A protagonist must choose to change their strategy or stay the course, and the results of this decision will provide the story's central lesson. Often times this lesson is moral, but even morality entails a strategy. Following the ten commandments, of course, may be construed as a strategy for reaching heaven.

Ender's Game, the popular 1985 science-fiction novel by Orson Scott Card, reads like a game-theory case study. Humanity has inadvertently come into contact with an ant-like species of extra-terrestrials called "buggers," and two subsequent wars have been the result. As the next war looms on the horizon, humanity must train younger and younger soldiers. Ender, the protagonist, is taken from his home and enrolled in "Battle School," where he trains by playing war games with the other recruits. After earning high marks in Battle School, it is on to Command School, where the games are played on a much grander scale. Ender must devise ever-changing strategies in order to win the mock space battles. His military genius derives from his adaptability and his empathy, his ability to see the game through the eyes of his opponent. Outside of these trials, Ender is engaged in a much larger game. He wants to become a commander and save Earth from the buggers, but he wants to remain a good person while he's doing so. This will be a tough task. The goals conflict with each other at times, and all the while Ender fears that he shares the same violent nature as his sociopathic brother, Peter. "I am not a killer, Ender said to himself over and over. I am not Peter. No matter what Graff says, I'm not" (Card 34). Ender must tell himself these words in order to assuage his guilt and self-loathing after breaking another boy's arm. Imagine Ender's guilt when, in his final battle at Command School, he cheats to win the game, only to discover that the game is much more than a mere simulation, and his unorthodox strategy has eliminated the entire race of buggers.

Ender has accomplished his first goal at the expense of the second. He is a killer. He has committed genocide. Because of this failure, we, as readers, expect some level of tragedy in the ending, and we are satiated by Ender's overwhelming guilt. All hope cannot be lost, however. Ender's good intentions make him a sympathetic character, and we would be irritated to see the story end without hope for redemption. Thus, Ender begins a new game: atonement. His strategy is to rescue the buggers from extinction and tell the truth to future generations of humans, a goal that he triumphantly accomplishes in the sequel, Speaker for the Dead.

Throughout Ender's Game, Ender regards his peers and opponents like chess pieces. There are threats and allies, uses and obstacles. The revelation in the ending confirms what Card has hinted at all along: in spite of Ender's capacity as a leader, he too is a chess piece. He is a pawn in a game being played by his commanders. The goal is to thwart the bugger invasion. The strategy is to shape Ender into the perfect weapon. To do so, they must take his surroundings into account. In Battle School, Graff deliberately turns the other children against Ender in order to keep him surrounded by hostility and force him into asserting his leadership.

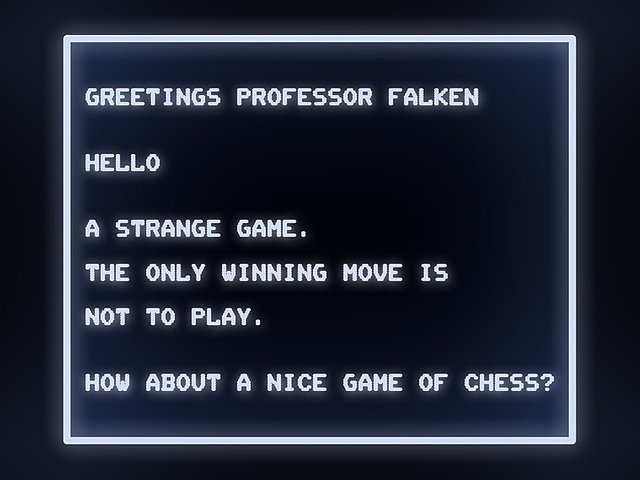

Ender's morality is also an issue. Graff knows that a child of Ender's empathy and moral conviction will have a hard time killing another creature. In order to make Ender kill buggers en masse, Graff must devise an elaborate trick. "It had to be a trick or you couldn't have done it," he says. "It's the bind we were in. We had to have a commander with so much empathy that he could think like the buggers, understand them and anticipate them. So much compassion that he could win the love of his underlings and work with them like a perfect machine, as perfect as the buggers. But somebody with that much compassion could never be the killer we needed. Could never go into battle willing to win at all costs" (Card 298).

Graff's subplot begs the question: are we all, inevitably, chess pieces? If every character is subject to manipulation from outside forces, if every decision can be treated mathematically, can anyone be said to act with true agency? Graff, too, is a chess piece in the eyes of the reader, along with every other character. When we read a novel, we are asked to place ourselves in the shoes of these characters, and consider their game and its variables. We apply game-theory in order to predict how their stories will play out, weighing different plausible endings with mathematical rigor. Consequently, the author must, in turn, consider the readers' expectations. The reader has learned nothing if there is no measure of surprise, but if the ending is too surprising, if it is directly contrary to our logic, we will undoubtedly dislike it. Ultimately, Ender's Game is a popular book because of its poetic justice, which is to say, the logical yet surprising (and therefore satisfying) resolution of its plot. We crave "poetic justice" in literature because we need it in our own lives. We want to believe that our actions are significant, and that everything will pan-out if we do the right thing.

Our narratives mirror our psychology. All of thought can be construed in terms of logical games: We have a goal, we consider the factors, and we consider what strategies would be appropriate for achieving this goal. As I write this paragraph, my goal is to make a coherent statement about human nature. The rules are the English language, and my strategy consists of translating my observation into words and sentences. Of course, this is only one out of an infinite number of examples. Even as we dwell in abstractions, there is always a goal. If we ponder something, our goal is to understand. If we are sitting around feeling sorry for ourselves, our goal is to vindicate our own displeasure.

It seems there are only two possibilities: Either life is genuinely one big game, or the game of life is an illusion, a construct of the mind, just like the myriad of games that compose it.

Buddhists endorse the latter theory, and it seems that Orson Scott Card does as well. The illusory nature of Ender's game-filled reality reminds us that all of knowledge is subjective. Ender's name is also a clear symbol. It's easy to equate his name with an end to the war, but in fact it goes much further. His name symbolizes an end to the games, and the beginning of truth. When Ender decides to cheat in his final battle, his expressly-stated motivation is an end to the games. "If I break this rule, they'll never let me be a commander... I'll never play a game again. And that is victory" (Card 293). The goal is the same in Buddhism. By casting out their desires and negating the ego, Buddhists hope to withdraw from the illusory games and achieve nirvana. However, in spite of the apparent mental health benefit, seeking nirvana implies a logical paradox, because the strategy consists of relinquishing all desires, which would presumably include the desire for nirvana. It is no wonder then, that Buddhism also asks us to let go of logic. "Don't think! Feeeeel!" Bruce Lee advises us in Enter the Dragon, and this advice doubles as a concise summary of Buddhist philosophy.

Much like the games that it describes, game-theory is an artificial construct, a subjective endeavor that we endow with meaning. Game-theory is only as useful as its models, and in reality there are always too many variables to predict an outcome with certainty. As observed by Tom Siegfried, game-theory deals in probabilities, not in certainties. Aristotle tells us that the greatest pleasure man can experience comes from learning, and game-theory attempts to provide this pleasure by pursuing logic to its limit-- but logic does indeed have a limit. As far as we know, there is no mathematical model for reality. Even in quantum physics, particles appear to behave absolutely irrationally. Scientists remain completely dumbfounded as they attempt to explain why an electron would appear here rather than there, and they are forced to rely on statistics and probabilities.

Perhaps the answer is that reality itself is irrational by rhetorical standards. It cannot be reduced to logical terms, players, strategies, or variables. It simply is, and the only way to escape the illusory games is to recognize them as such. The most frequent moral lesson throughout the history of narrative is that logic is insufficient, even corrosive. In the bible Adam and Eve are cursed by the tree of knowledge. In Oedipus the King a hero is doomed by his pursuit of knowledge. In Ender's Game logic without empathy is equated with sociopathy, as is the case with Ender's brother Peter. The fundamental lesson is that we must feel. If we regard life with logic alone, the trials never stop, and life itself becomes one big, grandiloquent game.

Cover Photo: Image Source

Magnificent article. How can you not remember the words of Shakespeare. Life is a game. Good luck to you and Love.

It is relatively complex to apply

Siempre traendo temas muy interesantes @yoydontsay. Saludos y feliz fin de semana

¡Te di un voto positivo en tu publicación! ¡Por favor, dame un siguiente voto!