Subverting the Scriptural Tradition (Part III):

Phillis Wheatley and the Birth of African American Consciousness.

Greetings, Steemians, continuing with the posts on first African American poet, Phillis Wheatley, here is the final part of the essay. Hope you enjoy it.

You can find the previous posts here:

https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/subverting-the-scriptural-tradition

https://steemit.com/english/@hlezama/subverting-the-scriptural-tradition-part-ii

Your comments, as always, are more than welcome!

Source

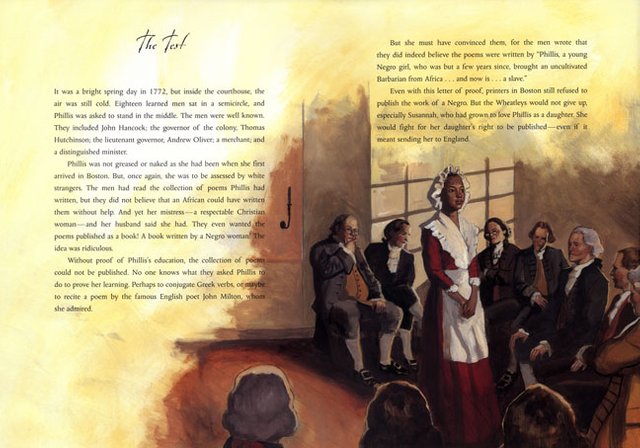

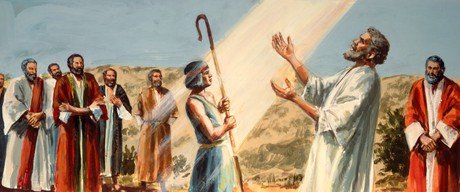

Source Goliath of Gath is probably the best example of Wheatley’s multilayered poesy. Although Wheatley must have had problems identifying herself with America’s independent cause, she understood the implications of an American triumph; it offered at least the possibility of constructing a logical argument against slavery. As a pioneering spokesperson who shattered the theory of black inferiority, Wheatley was aware of her role as the chosen one. Her choosing events such as the one narrated in On Isaiah and Goliath of Gath is not accidental; they are both about chosen people, about divine and social justice, about heroic vindication, and about achieving the impossible. If we read the poem as Wheatley's patriotic contribution to the American struggle for emancipation (which, as I have stated above, was also Wheatley’s cause), then David becomes a metaphor for America.

Source

SourceAt the racial level, I agree with Shields’ interpretation, “David becomes symbolic of slaves in revolt, trying to uphold God’s law,” which teaches ‘Christians’ that ‘Negros, black as Cain/ Maybe refin’d and join th’ angelic train’ (18)” (221). At a more personal level, there are many ways in which Phillis must have felt identified with David; both were very young, impetuous and talented; David was underestimated because he was the youngest, in similar ways Phillis was underestimated for being “inferior,” David was also envied once his merits were evident; Phillis must have faced all kinds of intrigues because of her privileges at the Wheatleys, and all the fame and notoriety that followed the publication of her first poem (the elegy to George Whitefield in 1770). "The parallel here is to Wheatley herself, defeating oppression with her pen” (Shields 221).

Source

SourceThe parallels do not end there; actually, the parallels begin in chapter 16 where Samuel is commanded by God to go to Bethlehem and anoint the new chosen king of Israel. David is chosen among his brothers in a scene that must have reminded Wheatley of her own purchase by the Wheatleys at the slave auction. Wheatley was not the best looking slave, as historical records tell us, but she was “chosen” despite appearances. “Do not consider his appearance or his height” God warns Samuel in 16:7; “there is still the youngest” must have sounded familiar to Wheatley (16:11), and David ruddiness, which in some Spanish versions of the bible is translated as “moreno” (brunette or colored), must have definitely established a link between the poet and the prophet.

Source

SourceThe parallels continue in chapter 18 with the rupture between David and Saul. In the same way Saul offers David protection, Phillis was also sheltered under the Wheatleys’ wing, but similarly to David’s story, that alliance was not meant to last forever. Envy enters stage and David’s ultimate destiny is to set free from Saul; under circumstances probably more similar than historical facts suggests, Phillis would eventually set free from the Wheatleys.

The epic features that characterize and distinguished Wheatley’s rendering of the David and Goliath story from other poets have already been described by Shields (American Aeneas 219-222), but my interest resides in the violence Wheatley magnifies from the original biblical text. As Scheick has pointed out, “Whereas for instance, Scripture reports that David’s ‘stone sunk into [Goliath’s] forehead’ (1 Samuel 17:49), Wheatley imagines that the stone ‘pierc’d the skull, and shattered all the brain’” (124). The biblical “cut off his head” becomes Wheatley’s “hew’d the ghastly head.” But she does not stop there, “The blood in gushing torrents drench’d the plains,/The soul found passage through the spouting veins.” This macabre end is not restricted only to the “giant monster,” but extended to his followers. The persecution of the Philistines by the peoples of Israel and Judah ends, according to the bible, with “dead...strewn along the Shaaraim road to Gath” (1 Samuel 17: 52). Wheatley, on the other hand, almost ecstatically, exclaims “What scenes of slaughter! And what seas of blood!/There Saul thy thousands grasp’d th’ impurpled [link to Isaiah] sand/In pangs of death the conquest of thine hand;” and, anticipating chapter 18, she highlights David’s feat, “thy ten thousands laid.”

Source

SourceTo add epic drama to Saul and David’s dialogue, Wheatley interposes a line that should be read as personal, “small is my tribe, but valiant in the fight.” That assertion, along with her emphasis on David’s origin, and the very title of the poem, where Goliath’s origin is also highlighted, suggest that Wheatley’s troubled mind struggled to separate individual actions from collective feelings; it can be argued that at a subconscious level, she spread the blame for all “evils past” on the whole white race (for actions or omissions) for whom she expected punishment (not precisely divine). But, at a conscious level, she knew that the only weapon she had was her pen, her heart, and her brain, all of which she would represent with tricksterish sagacity through her poetry, operating in her an almost therapeutic effect.

Source

SourceBoth Goliath and Isaiah are dramatically bloody narratives that suggests, in Wheatley’s work, more than a blind desire for war an understanding that there was not a peaceful way out of the social conflicts whites created with slavery; the vision went beyond the simple emancipation of the colonies from England. Because, as Wheatley very ironically interrogates in On the Death of General Wooster (1778), after invoking victory for the American cause,

“But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—

While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace

and hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?” (Wheatley 149-150, 27-32).

The interesting thing about this interrogation and the response that follows is that it is not the black poet’s voice who declares the internal injustices of the American cause, but the very General Wooster’s. If this statement does not make Wheatley an abolitionist I do not know what else can: “Let virtue reign—And thou accord our prayers/ Be victory our’s, and generous freedom theirs.”

Source

SourceWheatley’s “subtle war” was not only “against slavery” (O’Neale 157), but against her own demons. It can be argued then that Wheatley fought at least three simultaneous wars: a war to validate her approach to poetic art, especially her revolutionary notions on imagination, which she knew she had accomplished (despite, or probably because of the critics); a second war to claim a sense of belonging and identity, acknowledging the privileges she enjoyed (given the circumstances) in America, but at the same time denouncing what she knew everybody knew was an abomination, the institution of slavery; and a third more intimate war to reconcile her bereavement with her affiliation to her white patrons and intellectual mentors (white literature), to channel her repressed emotions through art without ending up in self-destruction or ostracism.

Source

SourceReligion did not tame Phillis Wheatley; it only provided her with avenues to direct her wrath. Her genius excelled those of her generation and actually I think it is about time to rephrase Thomas Jefferson’s desperate boomerang-like remark about Phillis, and with all the authority that recent scholarship in early American literature has produced, we should start saying that “religion, indeed, has produced” poets, “but it could not produce a” Phillis Wheatley.

Source

SourceGracias por la visita

Works Cited or Consulted

- Brooks, Joanna. American Lazarus. Religion and the Rise of African-American and Native American Literatures. Oxford U.P.: Oxford, 2003.

- Byles, Mather. Poems on Several Occasions. Columbia UP: New York, 1940.

- O’Neale, Sondra. “A Slave Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol.” EAL 21.2 (1986): 144-65.

- Scheick, William J. “Subjection and Prophesy” College Literature 22.3 (1995): 122-29.

- Shields, John C. The American Aeneas. University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, 2001

- ---. “Phillis Wheatley's Use of Classicism.” American Literature 52 (1980): 97-111.

- ---. “Phillis Wheatley and Mather Byles: A Study in Literary Relationship.” CLA 23.4 (1980): 377-90.

- Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works. Ed. John Shields. Oxford UP: Oxford, 1988.

Congratulations @hlezama! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

To support your work, I also upvoted your post!

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

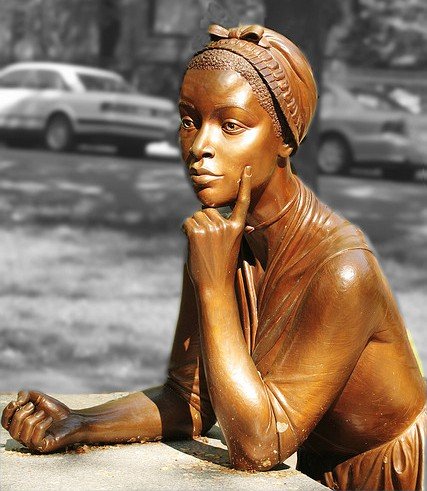

STOPWe simply love the sculpture. One of the most beautiful ever seen. Going to resteem and read later. Looks.like a great article after a quick skim. 😎😎

Thanks for the visit and comment. Hope you like it. I am also fascinated by that sculpture. I could not help including pictures of it in the 3 posts :)

Will check out the other posts when i have time 😎😎

Hi, I like the way you write articles. I will follow you, I hope you will follow & vote me, as we are interested in one topic. Let's increase the power of Steemit together!

Thanks for your visit. I'll be checking your blog shortly.

She was really a revolutionist. It is interesting all thedemons she had to fight to stand up for what she believed. Great work!

Thanks. Sadly, she died poor and forgotten, but i think she was more than aware of the impact her work would have in the future

Mi hermaniiiito!! de joooooooooooooooooooooróóóóóóón!!!!!

Hola. Gracias! El que persevera vence, dicen por ahí. Gracias por el apoyo.

Your Post Has Been Featured on @Resteemable!

Feature any Steemit post using resteemit.com!

How It Works:

1. Take Any Steemit URL

2. Erase

https://3. Type

reGet Featured Instantly & Featured Posts are voted every 2.4hrs

Join the Curation Team Here | Vote Resteemable for Witness

Thanks for the attention given to thispost.

Muy Interesante, a pesar de mi superficial conocimiento de la historia de EEUU , es increíble que La Biblia continué inspirando, como si las historias bíblicas guardaran todas las historias.

Gracias por la visita, @felixmarranz. Efectivamente, ese fue el secreto que descubrieron las culturas ancestrales. Por eso los amos procuraban mantener a sus esclavos en la ignorancia. Leer era un arma muy poderosa. Se les leía a los esclavos sólo aquellos pasajes de la Biblia que los mantenian subyugados, que supuestamente justificaban su condicion de servidumbre y que los amenazaban con terribles tormentos si desobedecían.

Pero aprendieron a leer y jugando el mismo juego, con las mismas reglas, lograron avanzar. La pelea sigue, en todos los planos (religioso, económico, político, etc.).