Anglicisms in the Spanish Language and Culture (Part I)

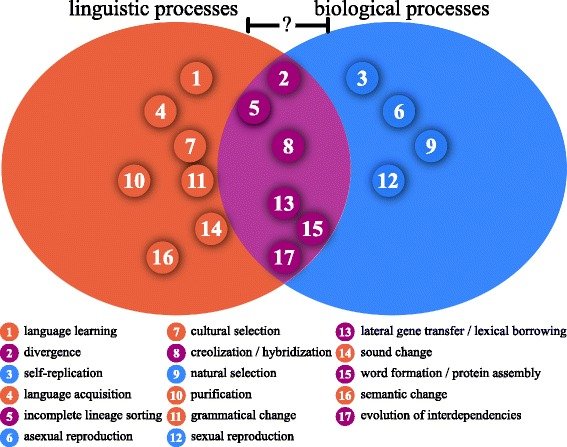

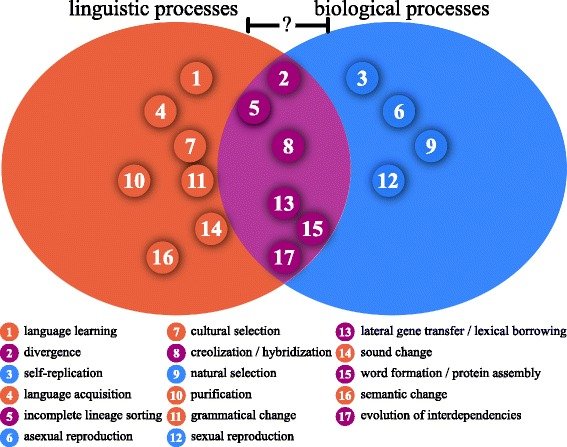

Greetings, friends of @adsactly. This time I want to share with you some of my research on Anglicisms, those words or phrases borrowed from the English language, that find their way into other languages, Spanish in this case, and cause quite a few arguments among conservative and liberal speakers. Lexical or linguistic borrowing is a common process among languages and English, as we know it today, is actually the result of quite a few loans.

Source

Source

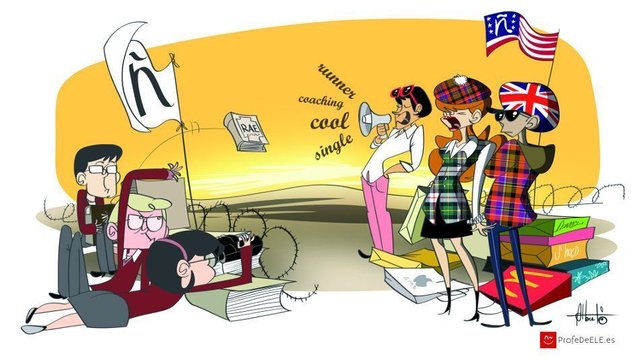

The linguistic borrowings from English that can be detected in the written and, more distinctly, in the spoken Spanish of Latin America, and Venezuela in particular, is neither a new nor a unique phenomenon. This process has become universal, inevitable, and even necessary. Despite the conservative and nationalistic arguments calling for the eradication of these “malign influences” (Tió 37), Anglicisms do not threaten the survival of Spanish as a distinct language in the Darwinian way academicians and other purists have theatrically declared. A brief analysis of Las Alfombras Gastadas del Grand Hotel Venezuela (The Worn Carpets of Gran Hotel Venezuela), a novel by Venezuelan author and journalist, Eloi Yague, will serve as an example of how English, far from affecting or reshaping the structure of Spanish into a more anglicized model, is contributing to its revitalization as it allows Spanish speakers to expand the creative capacity of their language.

In the twentieth century, the United States became the most powerful country in the world and Venezuela’s main economic ally. As this partnership strengthened, English words became another importable good. Venezuela’s technological, economic, and political dependence of the US applies to all Latin American countries. It is not surprising, then, to find Anglicisms in every Spanish-speaking country. As Richard Teschner says, “the penetration of Anglicisms is indeed [though only partly] due to commerce, tourism, the mass media, military intervention, and, in the case of Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone, territorial occupation” (683). The increasing cultural bombardment of the US and other English-speaking countries, facilitated by technological innovations and the boom of the Internet, have favored the globalization of this linguistic trend.

Source

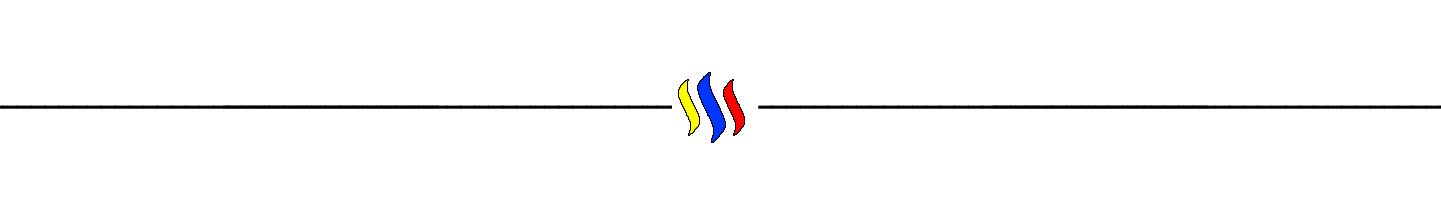

The use of Anglicisms varies, though, from country to country according to particular geographic and socio-political factors. Although Venezuela does not share the United States’ borders, as Mexico does, the political status of Puerto Rico, the linguistic status of Belize, or the proximity of Cuba, English has penetrated the language in a significant manner. However, one cannot refer to that “linguistic invasion” as Spanglish. That is a term more closely related to bilingualism. Besides, the use of Anglicisms, even at the syntactic level, does not require any of the socio-linguistic scenarios of bilingualism (Pratt 230).

The major concerns about the future of Spanish come, on the one hand, from Spanish linguists whose egocentrism makes them believe that they have been endowed by a divine providence to guard and preserve the language, not only the one spoken in Spain but also in Spanish America. An exponent of that movement is Ramon Sarmiento who, on behalf of Spanish academicians, manifested a serious concern for the increasing, almost epidemic, use of Anglicisms, putting the very existence of the Spanish language at stake,

... my deepest sympathy to Anglicisms and other –isms frequenters, not because of a ridiculous purist zeal, but because [they were] aware that by the crass ignorance of the equivalent Spanish expressions they demonstrate, they are also certifying their own idiomatic death and, by contagion that of the good Spanish speaker. (quoted by Kishida)

Source

Source

On the other hand, linguists from bilingual countries or countries with bilingual regions see with apprehension the example of Curacao and Aruba, where Spanish blended with English and Dutch and turned into papiamento, a completely different “anarchic and phonetically imprecise” language (Tió 25). An example from Puerto Rican literature better illustrates the purists’ fears:

Lo que la decidio fue el breathtaking poster de Fomento que vio en la travel agency del lobby de su building. El breathtaking poster mentado representaba una pareja de beautiful people holding hands en el funicular del Hotel Conquistador (Vega 75 my emphasis).

Although Ana Lydia Vega also writes in standard Spanish, she wrote this story deliberately to illustrate how English and Spanish overlap and coexist in Puerto Rico. In this case, an analysis of the Anglicisms used in Puerto Rico would be relatively easy, but in other Latin American countries where the contact with English in not so close or the contact with other languages has been significant, the study becomes complex and requires a more detailed philological and socio-linguistic approach.

Source

Source

In many Latin-American countries, and even in Spain, Anglicisms are not fully adopted until they have become quasi-Spanish forms. The regional variations of the same Anglicisms in different Spanish-speaking countries evidence a different dynamic that could be read as a resistance against what Pratt calls “patent” English forms. If the word entered the language orally it is possible that the changes in pronunciation make an accurate identification of the original source impossible. In some cases, the Spanish form of a word is so ambiguous that the origin can be attributed to native American languages, French, Latin, Arabic, or even German. Roca, for instance, can be associated to the English rock, the French rocaille, or the Arabic ruhh. The word switch has been adopted as chucho in Cuba and as suiche in Venezuela. This situation proves the limitations of a merely etymological methodology to identify the origin of the foreign word.

In this respect, Chris Pratt proposes extra-linguistic methods to determine whether a word is an Anglicism or not. Paradoxically, he defines Anglicisms as linguistic elements used in Spanish but with an English model as immediate etymon (Pratt 115). The concept of “immediate etymon” is problematic since it suggests an immediate recognition of the word based on etymological analyses. Pratt warns about the “patent Anglicisms” that could have been incorporated into Spanish through other languages, especially French. He also points to those neologisms that share Latin roots, the existing ones that have been used with an anglicized meaning, and those that have been already syntactically, morphologically or phonetically modified and assimilated as Spanish terms (57-8). Pratt’s work ratifies how difficult it is to categorize certain linguistic elements as Anglicism and how easy it can be for a scholar to slip on apparently anglicized forms that end up being already existing Spanish models.

Along these lines, Christopher Pountain’s article on syntactic Anglicisms constitutes an excellent companion for Pratt’s book. Pountain goes deeper than Pratt in the description of some syntactic models in Spanish attributed to English influence. That is the case of the passive voice, the gerund structure, noun/adjective inversion, and noun + noun combinations. Pountain concludes, “syntactic Anglicisms do not lead to significant innovation in Spanish, but rather encourage the fuller and more effective use of existing possibilities” (121). He also emphasizes the selectivity of the Spanish system that allows it to borrow only those “patterns [that] are an extension or further exploitation of those which already exist in the language” (110).

Source

Works Cited

Kishida, Maria José. “Los Angliscismos en Espanol. Puntos Para el Debate.” http://usuarios.iponet.es/ddt/anglicismos.htm

Pountain, Christopher J. “Syntactic Anglicisms in Spanish: Exploitation or Innovation?” The Changing Voices of Europe. Social and Political Changes and Their Linguistic Repercussions, Past, Present and Future. Eds. M. M. Parry, W.V. Davies and R.A.M. Temple. Cardiff: U of Wales P, 1994. 109-24.

Pratt, Chris. El Anglicismo en el Español Peninsular Contemporameo. Madrid: Gredos, 1980.

Teschner, Richard V. “Exploring the Role of Hispano in the Dissemination of Anglicisms in Spanish.” Foreign Language Annals 7 (1974): 681-93.

Tió, Salvador. Lengua Mayor. Ensayos Sobre el Español de Aquí y de Allá. Rio Piedras: Plaza Mayor, 1991.

Vega, Ana Lydia. “Pollito Chicken.” Vírgenes y Mártires: (Cuentos). Rio Piedras: Antillana, 1983.

Yague, Eloi. Las Alfombras Gastadas del Gran Hotel Venezuela. Caracas: Planeta, 1999.

Click the coin below to join our Discord Server

)

We would greatly appreciate your witness vote

To vote for @adsactly-witness please click the link above, then find "adsactly-witness" and click the upvote arrow or scroll to the bottom and type "adsactly-witness" in the box

Thank You

Source

Source

)

Very good job! Working with young people, the experience I have with anglicism is closer and more recurrent. The language is arbitrary and mobile, it transforms, so many times the speaker is the one who sets the rules and sets the guidelines in that transformation. While it is true that there has always been the assimilation of other languages by speakers, the use of networks, the Internet, television series and globalization itself has made this phenomenon more palpable. The Spanish Royal Academy has already had to put the language in its pocket and accept some "not so pure" words that are part of our language. Thank you for sharing, @hlezama.

Very true. Languages and those who speak it are ultimately the ones to determine the viability of certain changes or innovations. Some expressions catch on, others not so much, and yet others not at all. Like rebel children, languages resist normativity to a certain extent.

An extremely interesting and controversial topic, @hlezama; I imagine not only in the English-Spanish relationship.

In order to be alive, languages must be modified, enriched, and this renewal will come, as one of its main ways, from the assimilation of words from other languages (as has happened historically). Speaking on the subject of fidelity to language, Octavio Paz says in one of his essays an ironic phrase that I like very much: "The worst infidelity is casticism".

What worries me the most are the syntactic turns that have been traced or transferred unconsciously.

After all, the central problem is - in my opinion - in the formation that the speakers have of their native language, which would come fundamentally from the education received. And there we stumble upon a harsh reality: our educational system - which I believe is almost universal - is not solidly forming our speakers.

Greetings.

You have pointed at a very important issue. I think that it is undeniable that we are having a serious decline in the, how can we put it, linguistic proficiency in our young generation. That poses a future problem and a dilemma. I can see there are reasons to worry if on top of a low proficiency in the mother tongue, speakers are going to incorporate common/populat expressions from other languages. What would happen with the standard language, and by extension to literary language?

I think that our educational systems must be better equipped to provide the best and demand the best from our kids so that the incorporation of foreign words does not represent any cause for alarm.

I do worry that most kids these days (and I can only speak about my inmediate reality) can't speak well or read and comprehend standard spanish.

This culture is wonderful to learn about

Posted using Partiko Android

Thanks for stopping by. Glad to contribute to cultural awareness

You are welcome

Posted using Partiko Android

I am going to assume Henrry wrote this, because it looks like his carefully researched, put together, and informative work. Well done! Put your name on it! Am I wrong?

Very interesting.

Haha. Thanks, @owasco. I had not noticed my name was not on it.

It gets more interesting in the second part :)

@adsactly, This world is filled with the Diversified languages and some languages blends and collaborates with different one and this combination brings out very unique language forms.

Posted using Partiko Android

True. Some people want the economic perks of cultural contact without the burden of cultural "corruption"; that includes language. It's a historic drama that repeats itself once and again. Languages, like all living things, have to deal with life cycles. Some are doomed to perish, others adapt and survive.

True.

Posted using Partiko Android

Lol👍

Posted using Partiko Android

Cambia STEEM y SBD de forma fácil y conveniente a Bolívares o Pesos. Bienvenidos a la economia del futuro https://Cryptolocal.Exchange

Hi, @adsactly!

You just got a 0.35% upvote from SteemPlus!

To get higher upvotes, earn more SteemPlus Points (SPP). On your Steemit wallet, check your SPP balance and click on "How to earn SPP?" to find out all the ways to earn.

If you're not using SteemPlus yet, please check our last posts in here to see the many ways in which SteemPlus can improve your Steem experience on Steemit and Busy.

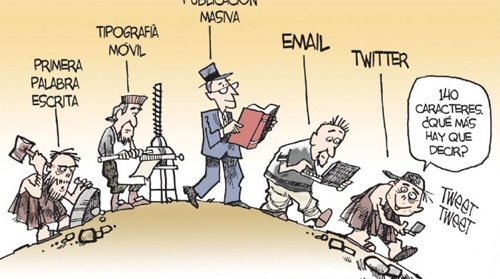

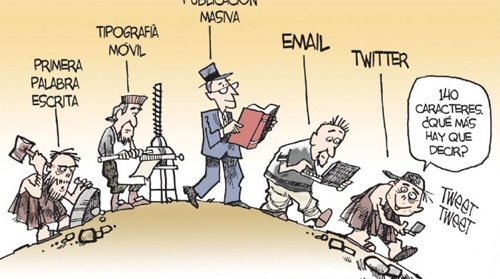

A full educational publication. In addition to the anglicisms in the Spanish language there is the penetration of other "modern" words that are used in everyday life because they themselves are concepts or have no translation (my assessment). For example, in a cartoon that shows in the post the word twitter (social network of micro blogging) appears. This word has been Castilianized (tweetear:: verb; tweeteando: action). Or other words such as software, hardware or betamax that are used in common language without any translation. A great pleasure to have read. Regards @hlezama