Blackout (An original short story)

Nowadays, we take some inventions for granted. Yet, American Indians, for example, have never literally “reinvented the wheel.” In this short story, I am exploring a possibility that paper has never been invented.

BLACKOUT

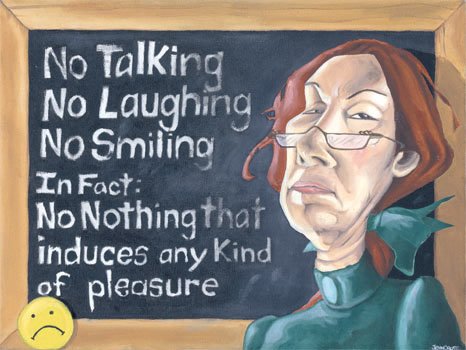

“And now we are going to practice a dictation. You should be aware that you’ll be tested on the vocabulary words you were supposed to study at home. Now everyone... Be quiet!”

Mrs. Williams clapped and looked over the class from underneath her glasses. Being apparently satisfied at the state of the affairs she continued.

“Now move everything from your desks except for your black pads and pens and mentally prepare yourselves to listen. It’s a very interesting story.” She gave the class another look as if making sure that there were no obvious signs of malice and continued. “It’s a story about the origin of writing.”

She waited until all the children followed her directions and then started reading slowly, distinctly pronouncing every word. Sometimes she stopped and looked over the heads making sure that all the children kept up.

“Language existed long before writing. It started from oral communication and replaced the gestures still used by apes. The transfer of ideas from one person to another, or to a group, was recorded perhaps as long ago as 30,000 years ago in a form of humans painting pictures on cave walls.

The origin of a writing, however, seems to coincide with the transition to agricultural societies when it became necessary to count one’s property, whether it be land, animals or measures of grain.”

Mrs. Williams then read about counting tokens and tokens eventually becoming symbols. Then she continued to talk about Mesopotamian cultures, clay tablets, and scrolls of Egyptian papyrus. She mentioned that in spite of advances of the human mind in many other areas the writing media had never actually improved only until recently when the pads with the moving black strips were invented, which made writing with white ink so much easier. She also mentioned that in China around 100 AD they were attempts to invent other writing media, but they had never amounted to anything substantial.

The thought that caused the tear wasn’t a thought of death. This realization of the physical disintegration and eventual collapse of his outer membrane didn’t bother him.

Ts’ai Lun was a great engineer of his time. He seemed to know everything from the construction of a complex stone or fireball-throwing machine to designing a beautiful building, to the minute details of silk production. He even was able to figure out how to increase the rice crop twofold on the same land. The word of his wisdom passed way beyond his small native Lien-Yang and spread all over the great land of China. Even the great Emperor Hi-Ti acknowledged his presence and delegated the most complicated and delicate projects to him.

But underneath his competent speech and confident manners deep inside himself Ts’ai Lun knew that all this was a trifle, not sufficient for greatness.

His family gathered around his death bed and waited. Ts’ai Lun had nothing to reproach himself. He was a good father and husband. He could see grief-stricken and stern faces of his sons and tear stained eyes of his wives and daughters. All his sons grew up as worthy people useful members of society. His older son Yen became a military engineer, next three were army officers, Mu studied medicine and enjoyed the popularity of his own. Even his youngest son Kai did well. He had his own market stands in several Chinese cities and as a merchant was traveling as far as India and Khoresm. His daughters were married into successful families and bore healthy offspring. He could be sure of the future.

But all this was a glamorous façade. It’s not that he was against people caring for their children. Rather he believed their obligations didn’t stop there. Because if people would live for the sake of their children only and their children live for the sake of children of their own then the entire humanity would live for its sheer survival. ‘And if we were to live for the sheer survival only we could as well be oysters’ he often chuckled. A real person has to leave a legacy after himself.

Ts’ai Lun understood that this great engineering mind of his wasn’t given to him by accident, that in his life he had a mission to accomplish. All his life Ts’ai Lun tried to find out what this mission was. And what a bitter irony that the realization came to him only now while he was looking at the ornaments on the walls that reminded a hieroglyphic writing. Now, when he was on the brink of death, with no energy in his body and soul and even his tongue was disobeying him. The thought that tortured Ts’ai Lun was a thought of Papyrifera.

One day two years ago Ts’ai Lun went to the public baths and ordered a separate wooden tub. Ts’ai Lun could afford comfort so he ordered the water to be aromatized. Usually, this was accomplished by adding a bark of eucalyptus or aloe to the hot water. This time, though the bark didn’t give any smell. When Ts’ai Lun grabbed a piece, he realized it wasn’t the bark of eucalyptus or aloe, but Papyrifera. Bushes of Papyrifera grew all around the city of Lei-Yang. This tree wasn’t notable for anything special. Boiled bark smeared under the pressure of his fingers. ‘What negligence!’ Ts’ai Lun thought. ‘I am going to complain to the bath master.’ And he put the piece of the smeared bark outside the tub.

When bathing was finished, Ts’ai Lun picked up the piece of bark and brought it to the office of the bath house master. Ts’ai Lun threw the bark on the floor and started pounding on it angrily.

“What is it? What is it? Why did you disrespect me so much?” Ts’ai Lun did such a thorough job with his cane that soft fibers from inside the bark came out.

Tzian Ze Bao the bath master stood silently in front of him with his face slowly acquiring a healthy orange color. Ts’ai Lun was a powerful man around Lei-Yang. Sweat started dripping off Tzian Ze Bao’s forehead.

“I am very sorry master Ts’ai, very… very sorry. This won’t happen again. The worker who made such an unforgiving mistake will be fired. Don’t worry, don’t worry Master Ts’ai,” he mattered with servility.

“Why to fire a worker?” continued Ts’ai Lun. “It’s obviously your fault! You were the one who ordered to use Papyrifera bark instead of the aromatized bark to cut the cost. You are the one who should be punished. I paid for the aromatized bath and I expected to get the right service!”

The bath master kept on apologizing, returned Ts’ai Lun’s money back and even promised him that his next bath visits would be completely free until the end of the year.

Ts’ai Lun accepted the apology but still was angry inside and not sure of the extent of the punishment, picked up the smashed bark piece and put it in the pocket of his robe.

When a couple of porters finally carried him home, Ts’ai Lun placed the bark on a flat wooden block to be used later as evidence.

In the morning, however, the bark looked quite different. The mashed soft fibers dried up and become a piece of some new material no one has ever seen before. It was flat to a touch, pliable and fairly strong.

His grandson, Yen, also paid attention to the object.

“What is it for, grandpa?”

“Nothing. It’s just a dried up bark.”

Ts’ai Lun’s answer was confident as usual, but inside he wasn’t sure. Logic told him that this property of the bark is a novelty at best. And yet something else, something beyond plain reason told him that it wasn’t. This entity, an obscure dark tangled ball of strings, rotated somewhere in his thought space, like an object of purpose yet to be defined.

And only now when Ts’ai Lun was on his death bed, he understood the possible application of Papyrifera. The idea stuck him like the lightning. Everything became painfully obvious. If it was boiled until soft, pounded until the fiber separated, then dried, a new material could be made. This new material, that was light, pliable, yet strong and could have been used for writing.

Ts’ai Lun has stretched his arm outward and beckoned. His older son Yen respectfully approached and sat on his knee by Ts’ai Lun.

“Yes, father?”

The only thing Ts’ai Lun could wheeze was “Papyrifera”.

“What father?” Yen asked, not being sure that he understood what Ts’ai Lun was talking about. “Are you hungry, thirsty, do you want me to change your position?”

“Papyrifera” Ts’ai Lun wheezed again.

“What is he saying?” everybody asked stretching their necks.

Yen turned to them and lifted his brows in a gesture of bewilderment.

“Our father’s great mind is probably departing his body.” Said he out loud and nodded his head in sadness.

“Papyrifera,” said Ts’ai Lun this time quietly but distinctly collecting all his remaining strength. His children understood that Ts’ai Lun was trying to tell them something important, but they didn’t know what.

Mrs. Williams’s hawk’s eye noticed some commotion at the last row. “Sean, what’s going on there? Didn’t I say no talking?”

“I’m not talking Mrs. Williams. I only asked Timothy for a black out.”

Mrs. Williams made her way to the last row and looked at Sean Edwards’ black pad. His last sentence was indeed a mess of the white ink.”

“I see. It’s ok, Sean. You don’t need to black it out. Just write the sentence over on the bottom. Accidents happened.”