Fast Music Theory: Rhythm

This post is the second chapter of the pre-release of my book Fast Music Theory: Understanding the Language of Music in Record Time. To catch up on the notes we use for our western musical system, check out Chapter One: 12 Tones. For my introduction and the reason behind this project, check out my first post. Follow me through this release to further understand the sonic landscapes that color your life on a daily basis!

CHAPTER TWO

Rhythm

“Life is about rhythm. We vibrate, our hearts are pumping blood, we are a rhythm machine, that’s what we are.”

-Mickey Hart

When a group is playing music, there is a fundamental glue holding them together: rhythm. Each musician is experiencing an internal clock that is ticking at the same speed as their companions’. Understanding the basics of musical counting and practicing your groove will cut the time it takes to learn new songs and get you jamming in no time.

The Beat

The basic pulse of a song is its beat. If you grew up liking music or being exposed to it through television, radio, or public places, you’re probably already good at finding the beat. Put on any song you like and tap your foot, snap your fingers, or clap your hands with it.

Aligning your mind with the beat will connect you to recordings and other musicians, as well as automatically make you a decent dancer (I’ve fooled my fair share of people). We can use the beat as a time metric as well, describing to somebody how long a note or section is in a song. This way of describing time is not like seconds or minutes, because a song can be played at many different speeds. The tempo, or speed, of a song determines how long each beat is. Slower songs have longer beats, faster songs have shorter beats.

LANGUAGE TIP: Tempo is measured in beats per minute, or BPM. In day- to-day usage, most people say “BPM” rather than “beats per minute,” as in, “the pulse at 60 BPM is in 1 second intervals.”

The Time Signature

Sometimes a beat isn’t a great metric to count by. 32 beats may be an accurate measurement for a part of a song but can be easy to mess up in a live situation. Thankfully every song comes equipped with a natural container for beats, called a measure. If your song holds 4 beats per measure, then your 32-beat count becomes an 8-measure count (32/4), which is much easier to keep track of. Here’s how it works:

The beginning of each piece of written music or song includes a pair of numbers, one above the other. This is the time signature.

This is called four-four time, and is traditionally the most common time signature (so much so that it is referred to as common time). The number on top tells you how many beats are in each measure. Here are some other common time signatures.

Three-four time (or just three-four for short) has three beats in each measure. Six-eight time has six beats per measure, but what’s up with the eight? The bottom number tells you what kind of note represents one beat, which we’ll cover soon.

NOTE: You don’t need to be good at reading music unless you want to play music that requires it (classical, large ensemble, some jazz, some worship, and more), and this is not a resource for learning to read music. The terms I cover in this book are aspects of written music that have been integrated into common language. Being able to read music can be helpful in a lot of unforeseen circumstances (and has certainly saved me on multiple occasions), but it is not a requirement to enjoy music making.

Notations

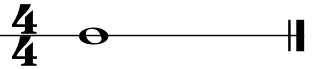

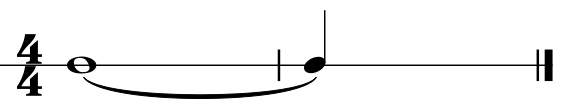

Here is a measure capable of holding four beats. The circle is called a whole note, and it lasts for four beats when played. In this instance, it takes up the whole measure, but a whole note is four beats in any musical context.

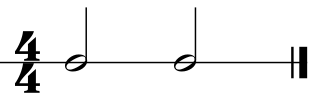

These are half notes: they last for two beats each. You can fit two of them in a 4/4 measure.

These are quarter notes: they last for one beat each. You can fit four of them in a 4/4 measure. See the pattern?

NOTE: Again, the names of these notes have nothing to do with what fraction of the measure they occupy. Whatever the time signature is, a quarter note is still one beat.

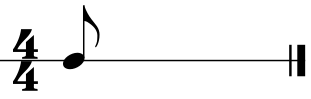

This fraction business goes on for a long time. At this point, we start using notes that are shorter than one beat. This is an eighth note: it lasts for half of a beat.

That’s what an eighth note looks like when isolated. However, when you start throwing around notes shorter than one beat, they start to group together. It’s easier to read and count.

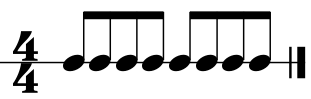

One more; these are sixteenth notes grouped together. This is by no means the smallest value found in music, but it’s the smallest that we commonly talk about. They are a quarter of a beat each.

We seem to have skipped some important values. What if we want something to last five beats, but we can only contain four beats in one measure? We can add notes together with a tie. This is a whole note and a quarter note tied together. Their values add to five beats.

Here are two and a half beats tied together.

There’s one more important value to consider: the dot. A dot takes half the value of a note and adds it to the original value. It’s easier than it sounds.

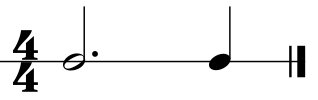

Consider a dotted half note:

1. A half note lasts 2 beats

2. Half of 2 beats is 1 beat

3. 1 beat plus the original 2 beats is 3 beats

Therefore a dotted half note is 3 beats! I’ve added a quarter note to fill up the remaining space in the measure.

You’ll see dots in a few other circumstances. Here’s one of the most common, a dotted quarter note.

1. A quarter note lasts 1 beat

2. Half of 1 is 1/2

3. 1/2 plus the original 1 is 1 1/2

4. Therefore a dotted quarter note is 11/2 beats!

A dotted quarter note is usually accompanied by an eighth note, adding up to two beats. I’ve added a half note to fill up the remaining space in the measure.

A dotted quarter note (11/2 beats) plus an eighth note (1/2 beat) plus a half note (2 beats) equals the total number of beats a 4/4 measure can hold (4 beats).

Rests

We also have symbols to represent silence, called rests. Here are the rest equivalents of the notes you just learned.

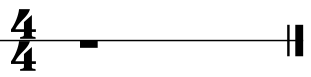

Whole rest

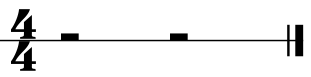

Half rests

MEMORIZATION TIP: A whole-gentleman takes his hat all the way off for you, and a half-gentleman only tips his hat to you.

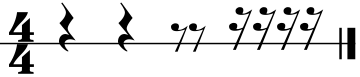

Quarter rests, eighth rests, and sixteenth rests are in this next example. This measure is full; see if you can add the values together to get four beats.

ONE LAST NOTE ON TIME SIGNATURES: The number on top represents the number of beats in each measure, and the number on bottom represents what kind of note is considered a beat within this context. So a 5/4 time signature signifies “five quarter notes in each measure,” and 6/8 signifies “six eighth notes in each measure.”

ADVANCED: Tuplets

Tuplets are complex notations that fit odd numbers of notes into the same space as an even number of notes. Three quarter note triplets would take up the same number of beats as two quarter notes. 5 quarter note quintuplets would take up the same number of beats as four quarter notes.

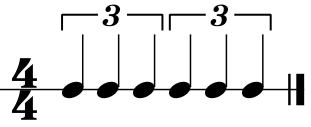

These six quarter note triplets take up the same amount of time as four normal quarter notes. They occur faster than normal quarter notes and slower than eighth notes.

Counting

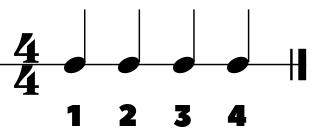

Now that you know what these notations mean, we need to learn how to communicate specific rhythms with speech. We do this with a counting system. How high you count in each measure is dependent on the time signature. When you begin a new measure, the count always begins again at 1.

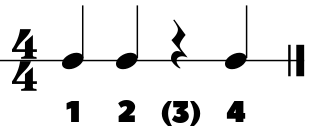

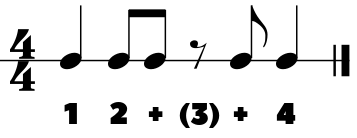

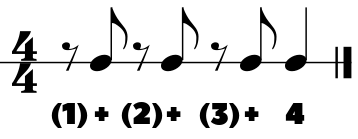

We don’t count out loud during rests, but we do allow those beats to pass in the same amount of time. Or, a measure full of quarter notes and a measure full of rests should take the same amount of time before the first beat of the next measure begins. I’ve put parentheses on counts that are rests. A good idea at this point is to add a bodily movement to the pulse of the beat: clapping, tapping your foot, or patting your leg are all good options.

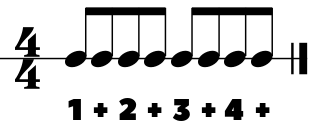

When we begin to split the beat into smaller parts, we use the word “and” between each numbered beat. We use a + to indicate “ands.”

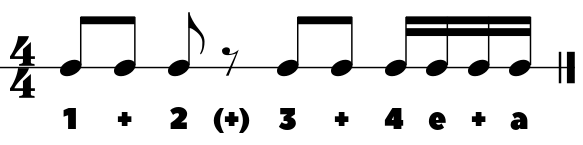

Let’s practice. Try to count these measures. Again, beats in parentheses are not to be counted out loud, but their timing still needs to be present.

LANGUAGE TIP: We can describe musical events with language like this: “That note lasts until beat 4.” “This doesn’t happen until the “and” of 2.”

When we split each beat into sixteenth notes, we have extra syllables to add that are not quite as literal as the word “and.”

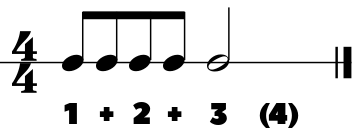

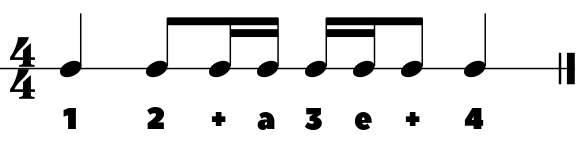

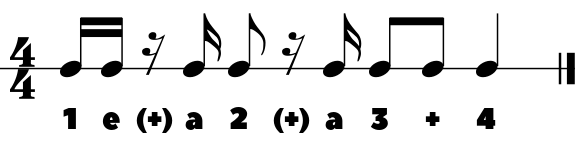

Here we say “one-ee-and-uh two-ee-and-uh three-ee-and-uh four-ee-and-uh.” Let’s try some complex examples. Notice that eighth notes and sixteenth notes tend to group together into one-beat groups.

Need to explain the rhythm of one of your ideas? This is without a doubt the quickest and clearest way to communicate or understand rhythmic patterns.

Not so tough, huh? It might take some getting used to, but these principles make up the fundamental building blocks of musical understanding. Remember, you don't need to play music to understand these principles. Impress your date on the dance floor, join in on the conversation with your musician friends, and break down exactly what it is about that drum solo that you love so much.

Have a music theory question? You can always drop one here.

Was this easy to understand? If not, let me know so I can make the language clearer. Follow me for Chapter 3: Melody and Harmony. Thanks again, Steemit!

Hey thanks for this breakdown. Gonna try to digest all this info and try to understand haha.

Of course! Let me know if there's a principle you're stuck on that I can help with.

Wow , 2 posts over 200$ youre killing it!, id love a resteem from you, you seem to have the right people listening!, also thanks for the great lessons, sometimes this stuff is hard to understand

May be beginner's luck. Thanks for the resteem!

dude this series is awesome!!!!

Thanks, what app I should use to make ?

What would you like to make?

Excellent resource! Specially useful for beginners or even kids.