Making Montresor: The Nemesis as Protagonist

I'm taking a break from a series on archetypes to talk about how to make a protagonist with evil motives.

First, I want to take a look at Edgar Allan Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado", which has one of the best examples of a "villainous protagonist" in fiction.

Then I'll talk overall about villainous protagonists and how to make them interesting without making them lose appeal with audiences, their archetypal role in stories, and how to bring them into games.

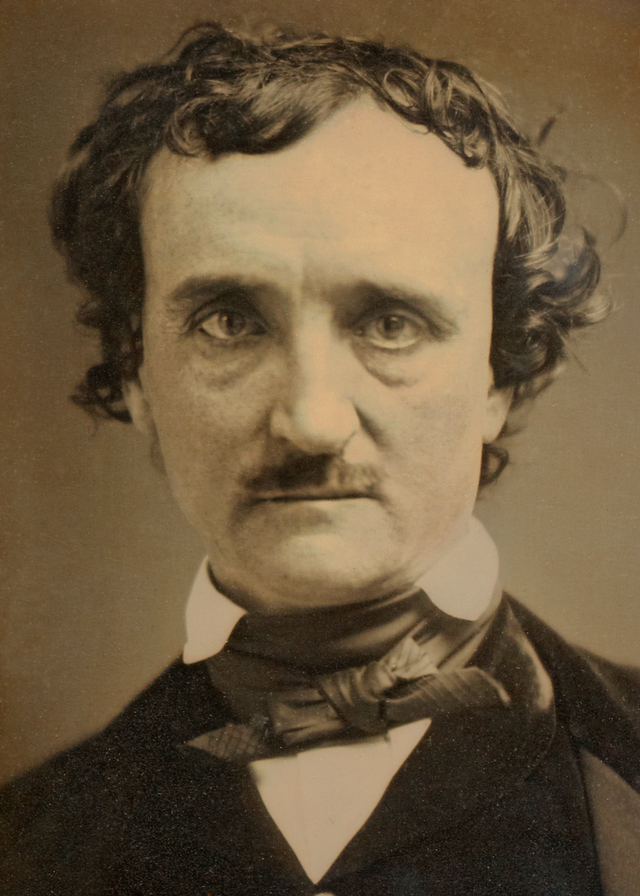

Edgar Allan Poe, by an unknown photographer

"Montresor! What are you doing!?"

One of the things in "The Cask of Amontillado" that is most important to realize is that Montresor, though clearly a villainous figure by our definition–after all, leading someone down to a vault and entombing them alive is not something that is considered a bit of good sport on the weekends–still views himself as justified.

His actions are motivated by revenge, which is simultaneously condemned (after all, an eye for an eye makes the whole world blind), but also something which is very important: we respect the right of the injured to demand reparation.

Montresor views his victim, Fortunato, as a person who is worthy of scorn because he has brought dishonor and shame to the Montresor name. His own upbringing as a scion of the Montresors includes the family motto–"nemo me impune lacessit" or "nobody harms me with impunity"–and with it the code of ethics and honor that it entails.

Fortunato, though not depicted as a wholly villainous person, is a drunken cretin who doesn't realize what he has done. From a strictly logical perspective, we would be inclined to forgive Fortunato, bumbling as he is, because to us as objective third-party observers he has merely insulted someone, probably in drunkenness (though the extent to which Fortunato drinks could be exaggerated by Montresor, our narrator), but inadvertently and without intending harm.

Montresor telling the story is a key element. Without a sense of context like this, we would likely see a different picture of events. Montresor is exonerated and made into a nemesis–a divine instrument of justice–by his account of events, offering Fortunato chances to turn back and showing the various ways in which he shows carelessness and dishonor.

In a sense, Montresor is a precursor to Hannibal Lecter, whose own actions are based on encouraging civility and courtesy through a chain of sociopathic murders. Montresor and Lecter both pursue a "better world" through the elimination of those they view as nuisances; although psychopathic, they manage to maintain a certain amount of appeal and charm because they fail to recognize how incredibly beyond the moral horizon their actions fall (or cheerfully ignore this fact).

Montresor also reveals information about Fortunato that is intended to make us accept the fact that nothing of value is lost by his death.

On one hand, he portrays Fortunato as a fraud, knowing nothing of jewelry or art but claiming to do so to rip off wealthy foreigners. On the other, he paints him as a Stonemason, a member of a secret society, and therefore worth of distrust and suspicion (Poe's audience would likely have shared this animosity, or at least recognized that it existed and that Montresor was using this as a justification for his actions).

After he has nearly finished sealing in Fortunato, he changes his language from one of hatred and disdain to praise; as Fortunato sobers and realizes his fate–redeeming himself by coming to the realization that he has wronged Montresor–and the narrative ends with Montresor's invocation of in pace requiescat, offering a final moment of respect for a fallen adversary. This echoes the narrator's previous assertion that Fortunato was to be subject to "immolation" or sacrifice–Fortunato is killed because he has wronged Montresor, not because Montresor is petty and vain.

Of course, this is just Montresor's reasoning, and readers should be skeptical and distrust his account. Nonetheless, it is difficult to view Montresor as beyond redemption, his reasoning is flawed, but he does not seem to be willfully wicked; we would not expect him to turn on us, because we are not as rude as Fortunato.

In many ways, Montresor simply does what we would want to do to people who are rude and insulting, but are too bound by morality and humanity to do.

In his final exchange with Fortunato, Fortunato exclaims "For the love of God, Montresor!" when he realizes what Montresor is doing, and then Montresor echoes his words back: "Yes, for the love of God."

Montresor becomes the epitome of the Nemesis and earns a way to absolution by drawing a connection to the divine, claiming that not only is he right, but that he is on the side of justice. He cannot be accused of being wicked and blasphemous, or some evil firebrand seeking to destroy society (though a villainous protagonist can be focused on the society around them, if they have a good reason to be turned in that direction). He is simply taking up the role of God, acting in accordance with divine law–of course Montresor has done something wrong, but nothing that Fortunato hasn't deserved.

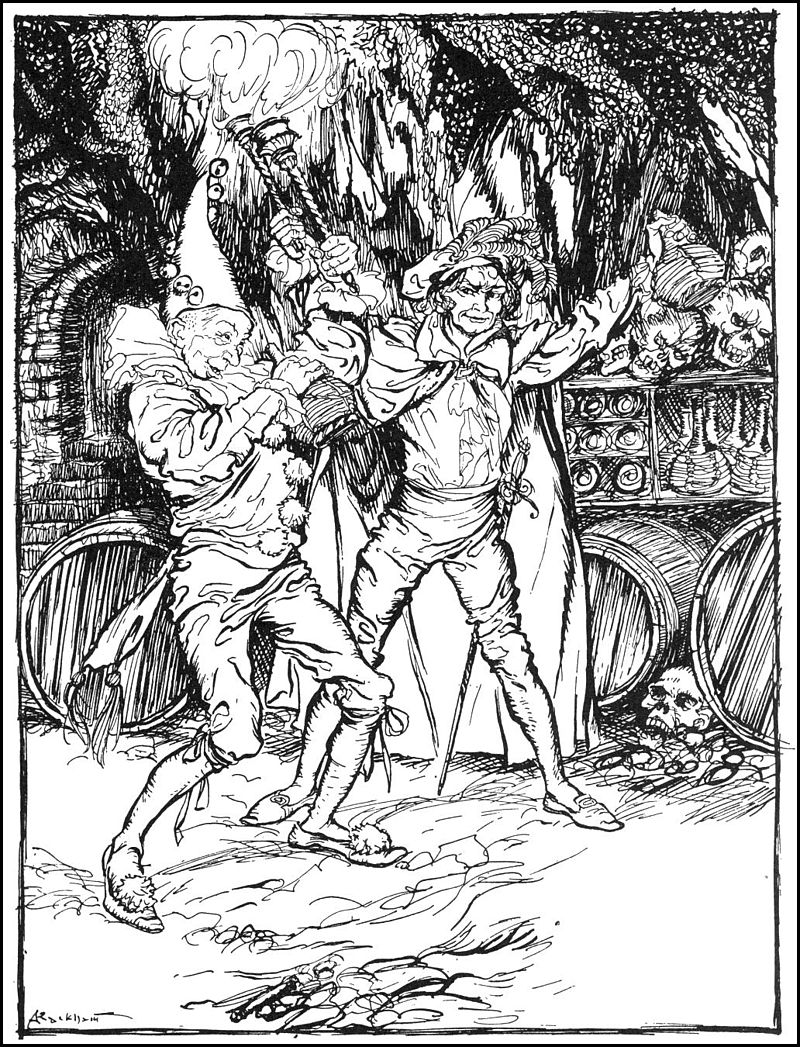

Fortunato and Montresor, illustrated by Arthur Rackham

The Nemesis as Protagonist

I've talked in depth about nemeses before, and I want to point out that the Nemesis archetype is not necessarily in direct opposition to the things we want protagonists to do.

The difference between the Nemesis and a typical hero is that the Nemesis channels their efforts not on some problem that needs to be solved, but on the person that is the source of that problem.

While the Nemesis can often be the sort of character we would consider to be "evil", there are times when we don't think of them as such. John Wick, the protagonist of a series of action movies, is an example of this: he kills more than 80 people in cold blood because they stole his car and killed his dog (and, to be fair, assaulted him in his home, though this happened before he began his rampage).

Yet we can root for John Wick, because we don't like people who steal cars, kill dogs, or assault us in our homes.

This brings some important considerations to light.

The Nemesis has to have a meaningful reason to believe that they are on the side of right. We see a lot of these sorts of characters becoming sympathetic starting with Romanticism, where prior to that they were either neutral (a force of nature) or evil (betraying the Truth of the universe for revenge).

A character like Javert in Victor Hugo's Les Miserables is a sympathetic villain; while he is wrong in his assumptions, he acts in accordance with his principles and values. He is a tragic figure, not a wicked one, and as such is worthy of our pity rather than our hate.

Likewise Montresor and the Nemesis in general as a protagonist has tragic elements to their psyches.

Typically, this Nemesis is driven by previous weakness or victimhood. The Punisher, Marvel's first iconic violent hero, has lost his family and is pursuing revenge. Montresor was insulted and had his family demeaned by Fortunato. Javert was born in poverty and squalor in a prison, and sought to distance himself from his low background by fully aligning himself, even without reason, to the law.

This gives them an excuse for their actions. While the audience will likely disagree with the nemesis-protagonist's methods, they will be willing to accept their motivations and as a result the character will not be viewed as an evil force or something that warrants destruction.

A mere tragic beginning is not enough, however, as this is true of many antagonists as well. A protagonist needs a goal, typically as part of a Hero's Journey, to make them worthy of struggle with. Montresor seeks to reclaim his honor. Frank Castle seeks to avenge his family. Javert wants to rise above what he is, despite holding a belief he cannot change.

Embracing a flaw or a weakness is typically an antagonistic trait. The tragic element comes when the character seeks to escape it, but is incapable of doing so, either due to mistakes, history, or unclear goals. For a protagonist to succeed, they need to rooted for, and the Nemesis will go beyond what society views as acceptable in their actions if not in the destruction and punishment they deal out.

A final point here is to point out that the nemesis protagonist still has to be a protagonist. A character who is too nasty or too extreme may lose their element of justification and cause conflict in the audiences. This can be the catalyst for a further fall, but it could also lead to issues: if they become unsympathetic and don't face consequences, it could alienate audiences.

The Nemesis Protagonist and the Archetypes

The Nemesis serving in a Protagonist role is almost always an example of Joseph Campbell's Hero archetype (or one of its variants, like the tragic hero or anti-hero).

The reason why a Hero becomes a Nemesis is because the focus of the Hero is to ascend to the ideal of their archetype. If this objective is denied, they will fall.

When thinking of the Nemesis as an archetype, it's important to consider them as a manifestation of Pearson's archetypes, which focus on personality.

To build an example from this, you might have a character who is a Warrior, whose growth depends on them having something to defend. Destroying their protectees locks them out of that stage of growth. They might be able to transcend it and become a protector of the whole or find a new object for their protection, but this is rare and is not necessarily enough to keep them from making the transition into a Nemesis.

When a character becomes a Nemesis, they have not necessarily lost their old nature. A Hero who is undergoing a Hero's Journey as a Warrior and loses everything (e.g. The Punisher, or Montresor if viewed through the lens of family honor) finds their original motive gone and their life disrupted.

This disruptive event leads them on the path to retaliation. Something has pushed them to the point where they reassess their goals and decide that the destruction of whatever caused their suffering is the new best goal for their lives.

The manner through which they pursue this will vary from example to example, with their personality obviously factoring in. A character like John Wick may totally transform, going from someone who sought peace and harmony, leaving the underworld after finding love, then return to a vengeful and violent lifestyle. This occurs in the Jason Bourne series as well, with Jason Bourne dealing out judgment for the crimes of the secret organization that created–and seeks

to destroy–him.

However, it is important to note that the Nemesis is merely a permutation applied to the other archetypes. The Nemesis is frustrated in their goal to the point that they change it, taking on an element of their worse side in an attempt to find their way back to the right course.

As a result, while the Nemesis can be a terrifying adversary, and make tremendous mistakes that harm others, but they do not fall victim to their weaker side without struggling against it; they are aware of the risks they take and bear them willingly, even sacrificially.

Using the Nemesis Protagonist in Games

The Nemesis as a protagonist relies on a very particular set of circumstances, and often it is taken for granted in games. While it is possible for a player in a tabletop roleplaying game to create a character with a backstory that sets them up for such a role, most games don't do anything to encourage this, the focus of the game's main rules and GM advice being on shared group experiences that largely leave little room for individual pursuits.

While incorporating a Nemesis into play as a protagonist requires special circumstances, there are things that can lead to it more closely. The important thing is that it must be a choice: people hunted and fighting for survival are merely fighting so they can continue to exist, not because they consider something so wicked it is worthy of destruction even if it brings about their own damnation.

To do this, all the setting needs is injustice that doesn't require a response from the players. A good storyteller can find this in everyday moments or in grand events, but makes sure that they do not lead players too far along a particular course. The Nemesis is self-making, building from an internal decision to abandon the self and pursue the objective.

To clarify, the Nemesis is nothing without a source of obsession. This obsession is negative and destructive, but protagonists bear it in the same manner as any tragic figure; they seek to overcome it, but cannot escape the patterns of behavior inherent to them.

The Nemesis has many advantages in games, especially social ones, that a regular tragic hero lacks. One of which is that the Nemesis may be able to find redemption following the completion of their goals, allowing for a standard Hero's Journey to be completed.

Since a tragic hero has to fall at the end of their journey, they have a hard time failing alone. In a game sense, this may mean that to have a tragic hero fall they need to strike out on their own or drag everyone else down with them, disrupting the normal flow of storytelling. In a group environment, this means that the rest of the players either disengage or are locked into following the same path as others. A Nemesis can be an influence on others, and be influenced by others, and still pursue their goals, no matter how abhorrent or unacceptable their means to do so may

be.

Whether a player pursues their character's role as a Nemesis independently or as part of the storyteller's efforts, it will turn into a journey of its own, but not a Hero's Journey. The pursuit of the Nemesis lies elsewhere, in the destruction of something profane or unworthy. Rather than seeking internal growth and a positive change for the world, the Nemesis has given up on growth–they may still feel they are changing the world for the better, but their objective begins to drown out the human element within their psyche.

To use the archetype effectively in a game, you need to think about how the character will grow and develop as they go along this journey. It is often one of decline and decay, making sacrifices that are intended to sow the seeds of destruction. As a result, Nemeses should not be confronted with challenges to overcome. They can do this as well as a Hero, but it does not further their development along the lines of their core agenda.

Rather the Nemesis faces sacrifices, and they must choose how far they will go.

Wrapping Up

The Nemesis makes an unlikely protagonist because their goals are destructive, rather than positive, in nature. They cannot claim innocence and pure intent, but what they rely on is their ability to still change the world for the better. Often the Nemesis is mistaken in their assertions of what good and evil are, but this is an honest flaw; they are limited by their situation and perceptions, not the lack of values and principles.

As a result, a Nemesis who strives for something in line with our expectations and desires can become a protagonist, someone who the audience is willing to root for and go along with. If love covers a multitude of sins, the monomaniacal pursuit of revenge or destruction can blind us to the flaws of a character, or make them more palatable, because their vision speaks to their integrity and strength.