The "plastic problem" of bioscience.

Unnoticed by the general public, research produces large amounts of plastic waste. But are there alternatives?

This is a translation of my recent post that was originally written in german.

How pixabay (CC0) and the world believe that we are working...

A personal problem

As most of my readers know, I work as a scientist in a chemical/biological lab. And I love my work. Science may sometimes be tedious, demanding and marked by setbacks, but it is also exciting (at least from time to time). It may sound a bit exaggerated, but I am happy to be able to push the limits of human knowledge a little further with every small success, and I know that many of my colleagues feel the same way. This is was motivates us to pursue our job, even as we could earn more money elsewhere.

However, the profession also has its downsides. One of them I write about today.

For a start, let me tell you that most of us bioscientists are very well aware of the state of our planet. Among us you will not find many deniers of anthropogenic climate change, and many of us actively engage for environmental protection - which of course also includes the reduction or recycling of waste.

Especially plastic waste poses great problems for the earth's ecosystems. The existence of huge plastic islands in the oceans is common knowledge, small particles, the so-called "microplastics", endanger fish and other aquatic animals, the chemicals released have an effect on the hormone balance and are therefore environmentally toxic (I reported), and also the proper disposal of polymers - burning - contributes to the increase in the CO2 content of our atmosphere. And I don't even start talking about the oil and chemicals that are consumed in the production of plastics.

It is no coincidence that politicians try to get rid of plastic bags by means of regulations, even if these often end counterproductively because of the prevailing incompetence (cardboard bags, for example, are only better if they are used several times).

Once again: We scientists know all this and generally worry about these things.

As long as it concerns leisure time.

In the lab... Well... Damn, how we produce dirty waste!

And by that I don't mean any chemicals at all. Contrary to popular belief, their consumption is barely perceptible compared to industry. No, it's actually about plastic.

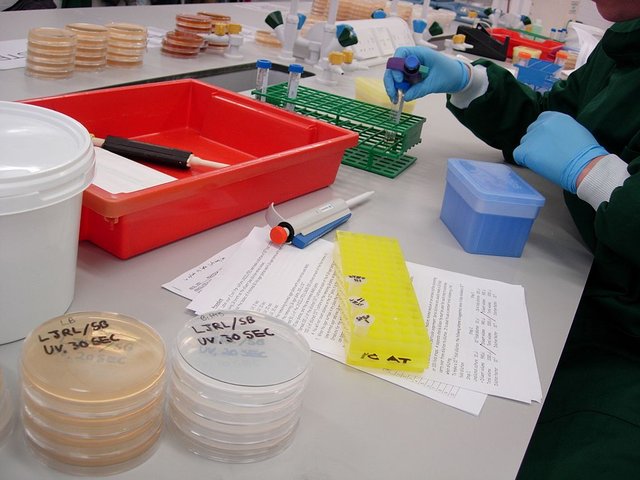

...and how we really work... by Laurence Livermore, CC-BY

Why that?

Life sciences in general and molecular biology in particular depend on disposable materials. Pipette tips, reaction vessels of all kinds, syringes, petri dishes and plastic bottles have many advantages over the glass products that scientists of old used:

- The cost. If you take into account the amount of time spent washing dishes, glass does not pay off at all. Not to mention the purchase price. Since science is a highly competitive field that chronically suffers from underfunding, a decisive point.

- "Stability." No breaking, no shards, no injuries, no trouble with lost samples.

- "Sterility." It is extremely important for us not to introduce any bacteria, yeasts or other contaminations into our experiments, otherwise they would become unusable. Plastic can be purchased sterile or, if necessary, can be sterilized relatively easily by ourself (most common method: autoclaving, i.e. heating under steam pressure), whereas - due to the small size of our dishes - this is much more difficult with glass, especially after reuse.

- "Size." Technology allows us to use ever smaller sample quantities for our experiments, which on the one hand reduces costs and on the other hand increases the "sample throughput", i.e. the quantity of samples that we can measure simultaneously. However, smaller volumes require us to work with ever smaller vessels. Due to their size, however, these are hardly or not washable, and glass is no longer suitable as a material. Ergo: Disposable plastic.

...with plastic...

The problem

For these reasons, science consumes extreme amounts of plastics. It is estimated that 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste is produced annually by bioscientists worldwide, which is almost equal to the amount of plastic that is recycled annually worldwide ref and accounts for almost 2% of global plastic waste.ref

And that's a problem we care about. Several calls and comments published in top journals such as Nature over the last years show that the topic is certainly being discussed in the community. According to the authors, science should be pioneering in environmental protection, and not the very last to jump on the "sustainability bandwagon".ref1, ref2

And of course, I fully agree... But what to do?

Solutions

Unfortunately, there are not too many ideas on how to escape dependence on disposable plastics.

Financial "candy"

In their Nature article, Urbina et al. propose that research funding should provide financial incentives for sustainability when paying for projects. ref

Hmmm, yeah, but...", says the learned skeptic in my head... "nice idea. But if research becomes more expensive, fewer projects can be financed." It's not to be expected that governments - in the age of ever shrinking budgets - will suddenly discover their love for science and come up with additional research budgets. And no scientist I know would want to accept not getting a grant just so that others can run their projects cleaner and greener.

Open the eyes

Of course, you can start with yourself. We are so used to disposable products in our daily lab routine that we often don't even think about taking glass instead. Hell, I don't even know where to find half of the glassware in my own lab. But it isn't necessary to use 50 ml Falcons for medium when there are sterilized glass Duran bottles available. It's not necessary to use a new tip for pipetting every time, and one can save plastics wherever possible.

Self-responsibility. Most of us could save a little, let's say 10%, of disposables without much problems.

But then, on the other hand, that means the remaining 90% are still necessary for research to work properly. I.e., even if all researchers would pull themselves together, we would still produce a relatively sick amount of waste.

Management

As Lopez et al. also suggest, we can contribute to the development of concepts to reduce the consumption of disposable goods at the management level.ref

Sure, a little more is always possible. But as long as costs, time and practical reasons are favouring plastics, this imo does not substancially change our dilemma.

Stop the research.

A point for the very funny ones of my readers. The production of 5.5 M tons of plastic waste a year is still MUCH better than stopping curing diseases and advancing humanity. My opinion.

...and plastic!

Conclusion

I have written this article (quite self-critically), although I know that it is water on the mills of those who are to be had for everything they consider "natural", and who think science is the devil's work.

But I am firmly convinced that we must also talk about this topic. We are not allowed to measure with double standards, we are committed to correctness, even when it concerns ourselves.

On the one hand, we researchers have to pull ourselves together and reduce our waste by the 10-20% (pure estimation on my part) which is probably possible without quality losses.

But above all, we need technological solutions that combine the financial and material benefits of disposable products with sustainable usability. Who should invent them, if not we ourselves?

If anyone of you, dear readers from related disciplines, has an idea on how to solve the problem, just bring it on. I even think there's not too little money in a good solution, so you could combine doing good with lambo!

Disclaimer:

In my blog, I'm stating my honest opinion as a researcher, not less and not more. Sometimes I make errors. Discuss and disagree with me - if you are bringing the better arguments, I might rethink.

This post has been rated by the user-run curation platform CI! In this platform users are able to manually curate content. This is done regardless of Steem Power, for both rewards and vote size calculation.

Join in at our site here!

https://collectiveintelligence.red/

Or join us on discord to interact with the community!

https://discord.gg/sx6dYxt

This post was submitted for curation by: @anevolvedmonkey

This post was given a rating of: 0.7537626055908596

This post was voted: 62.74%

Thank you for bringing this uncomfortable topic up. I appreciate this from one who actually works in this field. Takes also courage to do so.

I may be the devil's lawyer here, but I could question your bill so far when health research creates its own diseases, so to speak. The question must be justified without being driven out of the place for heresy.

I think this is a very difficult question, but science has to ask it itself. What dangers and how much chemical waste and residues are associated with diseases resulting from scientific research?

We do not have to go straight to the hammer and postulate that research should be discontinued. But is there a middle ground somewhere? If there are already professionals at work who are familiar with chemistry: are there no substitutes for plastics that can rot or be burned better?

Do you know anything about whether any scientists in the chemical industry are even dealing with this environmental problem? Perhaps you have heard of Michael Braungart? I am not competent to judge how good his cradle to cradle concept is. It would be interesting to hear something about it from you. Had I ever asked that before?

P.S. This could be a research field of it's own to ask the departments how that plastic problem in the labs could be solved and get started - it makes me mad that funds cannot be found for that. Maybe that is something people could do with the money they earn here. I would throw in some of my SP or SBD.

Thanks for the comment. I had to think a little on that one.

First off, the concept of heresy shouldn't exist in science. Second, even with the problems around plastics, I'm positive that a world with bioscientific process is better than one without. Without science, we wouldn't even know that plastics are bad. We would eat unhealthy, live unhealthy, and have no medical treatment when we get sick.

But of course, also science should aim at working as sustainable as reasonably possible. I am not aware of anyone working on a solution t the material chemistry front, but since there's growing awareness, I wouldn't be surprised.

I used a metaphorical expression as to point out that I perceive in general public an avoidance towards an approach that takes on a critical attitude towards science itself. I appreciate this a lot when scientists do openly talk about their blind spots in their particular field. .... maybe I should to some search for finding interesting debates on that.

The deeper meaning of my sentence points towards my way of agreeing with scientists who include a critical view on their scientific work. There are always downsides attached to "upsides". Solutions and cures - or the side effects of the methods - do not own only positive effects but negative as well. Here, you talked about the downside - I found that sensible.

In the circle of scientists themselves I can imagine that there is another form to deal with criticism in the sense of giving valuable feedback once the scientist agree on the fact that they are not only carrying responsibility for what is helpful but also for what is harmful.

You mentioned the missing funds and as far as I know this is always an issue within the sciences which do not work alone with the given applications of scientific findings but drive the investigation further. It makes sense to having the desire to work on problems which obviously do have negative impacts on the environment. One does not to have to exclude the other. I did not say that a world would be better of without bio scientific process.

I fully acknowledge the many applications science is providing us with. I would have liked an example which gives hope that there is actual new science in process which deals with the plastic problem in this field. I am not an expert and I would probably have more difficulties in doing a research if something is out there which can be dropped here in the comment section.

Well, there's research going on regarding the plastic problem in general: bio-degradable polymers, advanced waste-sorting machines, bacteria that can "eat" plastics, recycling plastics to a kind of oil, etc. etc.

Of course, should any of those techniques experience a breakthrough, this will have an impact on us aswell. But until that, I think we need to come up with some solutions of our own.

Plastic wastage in cell culture experiments is inevitable. However we do use the following to minimize the usage.

When working with cell lines to produce protein say - we use the same plate multiple times. Like you trypsinize the cells and seed new cells on trypsinized plate from mai3.5 cm maintenance plate.

For experiments that do not demand high sterility. Such as for storing buffers for commasie stain or silver stain we autoclave the used Falcons and reuse them. Even western blot buffers stay fine in them.

For liquid waste disposal we don't use plastic bottles and rather aspirate them in glass flasks. Which can then be emptied straight to the main disposal.

One thing that is hard to replace are pipette tips. I don't think there is a possible alternative to that .

We have taken some measures as well, but it still is a lot of plastics that we use.

I wonder about the sterility part - why is autoclaving glass considered difficult?

I've always had this perception that glass is better than plastic. Many plastic products do not sustain high temperatures, and I'm also worried that the plastic products do leech plastic - like, I think that many of the drinking water bottles that one can buy in the shop (or get for free with sponsor branding) adds plastic taste to the water. Further, when doing the dishwash it often seems to me that the plastic products isn't getting properly clean - the fat often seems to be sticking. A proper glass, when washed properly with soda and lots of hot water, seems to get "absolutely clean".

Of course, I do trust that the plastic products used in lab settings is good enough - and the cleanability-issue is not really relevant when discarding the products after usage.

In general, autoclaving glass is not difficult, and we do it every day with macro-sized lab material (flask with a volume of 100 ml+, large pipettes (10 ml+) etc.)

But given the ongoing miniturization in science, we use plastics for everything that requires volumes in the range of 1 µl - 10 ml. And we use A LOT of that stuff. At that scale, glassware is very hard to get clean and sterile once it is used. And ofc, glass only has an environmental advantage IF it can be reused.

That's what I meant with my sentence, thanks for pointing out the missing explaination.

I really believe that self-responsibility is the way to go. Instead of throwing away some plastic, we could ask ourselves what to do with it. Can we give it a second life? Do we really need to throw it away.

We are trying to live like that at home, buying alternatives with less plastic. Of course, this is not that sustainable at the level of a lab, but maybe finding a second life for all this ustensiles could be the way to go? Or thinking about what we could do with them?

I agree when life at home is concerned.

In a biolab, things are much more complicated. Finding a second life for thousands of small reaction tubes is quite a task.

The tubes may also be contaminated with carcinogens, bacteria, or other reagents that make recycling difficult.

This issue doesn't have any easy solutions, especially among labs with low funding.

That, obviously, is a good part of the problem. Ty for commenting.

Well written. The surplus amount of plastics usage makes the environment scream in terror. Science created plastics and it is the job of science to dispose it too. Removing totally plastics from our day to day job basis certainly is an impossible feat but what should we do is try to minimize the consumption. Sorry I couldn't contribute much because I'm from the medical field but this issue happens everywhere.

Thanks for you comment. I agree this issue happens everywhere. Where science is quite different to daily life is that we would want to reduce plastic useage, but there are no real alternatives for most applications.

True that. I’m glad at some places straws are banned and they are starting to charge plastic bags usage at the grocery stores.

I upvoted your post.

Best regards,

@Council

Posted using https://Steeming.com condenser site.

This post has been voted on by the steemstem curation team and voting trail.

There is more to SteemSTEM than just writing posts, check here for some more tips on being a community member. You can also join our discord here to get to know the rest of the community!

I like your post and good post I like your post and good topics write this post

And upvote me

I don't like your comment spam which is a bad comment span about no topic at all. And I downvote you. @steemflagrewards

Steem Flag Rewards mention comment has been approved! Thank you for reporting this abuse, @sco.

Your comment has been repeated multiple times without regard to the post. This post was submitted via our Discord Community channel. Check us out on the following link!

SFR Discord