Revisiting the War on Drugs & Its Impact

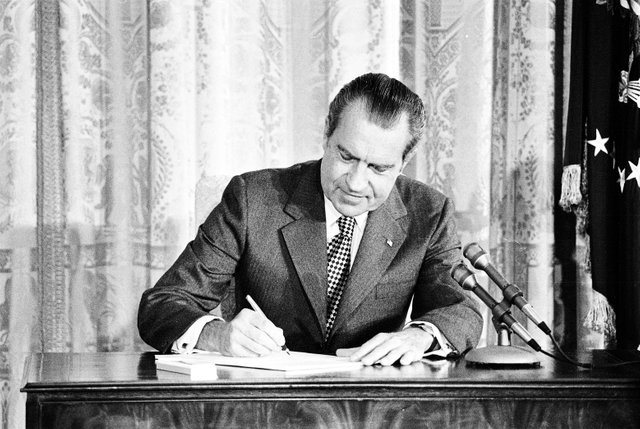

Nixon signing the Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act, 1972. (Courtesy National Archives, photo no. 66394272)

July 14 marked the 50th anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s message to Congress asking for the establishment of a federal plan to tackle substance abuse, citing a dramatic increase in juvenile arrests for drug offenses. Nixon’s letter was the start of a new era of American drug policy as, the following year, the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”) was passed, creating the foundation of the country’s current, five-category – or Schedule – system for handling substances and officially beginning America’s War on Drugs. While there are numerous pieces of legislation that contributed to the current national policy on drugs, many consider President Nixon’s initiation of an “all-out offensive” on drugs to be the watershed moment in setting the precedent of the nation’s modern drug enforcement policies.

Yet, in the 50 years since it’s initiation, the effectiveness of the policy is vehemently contested. In fact, the idea of legalizing several of the drugs initially banned by the CSA has steadily gained public momentum. Most Americans are aware of the movement to legalize cannabis, but that only scratches the surface of a much larger issue. Over the past five years, substances such as methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“MDMA”) and psilocybin – a hallucinogen found in many psychotropic mushrooms – have experienced a tremendous increase in scientific data regarding their medicinal potential and a corresponding surge in public interest about their use. This increase has produced a noticeable shift in public perception regarding psychedelic substances in 2019 alone, however, there are still enormous hurdles to clear before such substances’ medicinal potentials begin to be realized. Much like the challenges encountered by early movements to decriminalize and eventually legalize cannabis, these substances face significant legal obstacles, the pernicious threat of misinformation dissemination, and factually incorrect scare tactics regarding their risks.

Policy Origins

In order to fully understand the significance of psychedelic medicine’s newfound and still-developing potential, it is first necessary to understand how the initial policies of the War on Drugs were created and how it has historically impacted the research of drugs. Two years after his letter to the Senate, in 1971, Nixon appeared on television to formally declare the matter’s urgency, as well as his administration’s strategy to resolve the crisis, claiming, “America’s public enemy number one, in the United States, is drug abuse. In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new all-out offensive.”

Created to assist in waging Nixon’s War on Drugs, the Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”) was founded in 1973 and tasked with determining substances worthy of inclusion or removal from the CSA-established schedules along with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). According to the DEA, the Schedules are organized by “the drug’s acceptable medical use and the drug’s abuse or dependency potential,” with perceived abuse rate as the determining factor. As such, Schedule I is assigned to substances with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” implying a decreased potential for abuse in Schedules II – V.

With his intentions presented out of concern for the American people, Nixon’s decision to wage this new offensive to criminalize drug usage appeared to be purely a national health and safety concern. It was not until decades later that details revealing otherwise started to surface.

In 1994, author Dan Baum interviewed Watergate co-conspirator, John Ehrlichman, on the politics of drug prohibition during Ehrlichman’s time as Nixon’s former counsel and Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs. To Baum’s shock, Ehrlichman simplified the decision as a result of Nixon’s political adversaries:

"The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”1

The damage inflicted on Americans by this corrupt political duo is immeasurable and in a just world, they should have been tried for crimes against humanity. While particularly sickening, Nixon was not the first official to use drug criminalization against minority groups and/or perceived social competition. Several decades prior, lawmakers pushed to criminalize cannabis after an influx of Mexican immigrants displaced by the political upheaval of the Mexican Revolution began entering the U.S., bringing over one of their traditional means of intoxication – smoked cannabis or, in Spanish, “marihuana.”2 Despite some Americans already being familiar with the plant as “cannabis,” which was used in countless tinctures and medicines during the patent medicine boom in the mid-to-late 19th century, the foreignness of the term “marihuana” paired with the media’s xenophobic stereotypes of violent Mexican immigrants made many Americans uneasy.3 Mexican immigrants were not the only minority associated with cannabis usage, as New Orleans newspapers began linking the drug with African Americans and the emerging jazz scene as well.4

Some historians claim that the backlash towards these immigrants fueled the political debates on cannabis law in the 1930s due to the number of claims presented regarding minorities becoming aggressive or soliciting sex after using cannabis. According to congressional hearing transcripts from the 1930s, H. J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics (“FBN”), testified before Congress urging stricter cannabis regulation, including a letter from a Colorado newspaper editor stating:

"I wish I could show you what a small marihuana cigaret [sic] can do to one of our degenerate Spanish-speaking residents. That’s why our problem is so great; the greatest percentage of our population is composed of Spanish-speaking persons, most of who are low mentally, because of social and racial conditions.”5

The result of the cannabis hearings in the 1930s was the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. The bill did not fully criminalize cannabis, but imposed a tax on its production, sale, and possession, essentially becoming the first step in the U.S. plan to prohibit cannabis. The bill was later found to be unconstitutional in 1969 as a result of Leary v. United States on the grounds that it violated of the Fifth Amendment through requiring self-incrimination but was ultimately succeeded by the CSA the following year.

Consequences & Implications

As Ehrlichman noted, cannabis was a focal point of the War on Drugs from its inception, but other substances were quickly swept into the conflict and the anti-drug movement that it produced. Following the discovery of several questionable studies on the substance during the 1950s and 60s, psilocybin was included in the CSA, resulting in the complete halt of psilocybin research on humans for over two decades, research that was showing far more substantial potential than most Americans realized.6 With funds gradually seeping into psilocybin research in the 1990s, progress in changing public opinion through legitimate studies has been slow. Similarly, research on ibogaine, a moderately psychoactive indole alkaloid extracted from the Tabernathe iboga plant, was also prohibited during this time. Non-addictive by nature, ibogaine was historically used by some Central African tribes for social and religious purposes, but by the time its ability to combat opioid abuse was discovered, the CSA had made its clinical study near impossible simply because it shared some of the effects as other drugs already on Schedule I, despite being incredibly dissimilar chemically.7

Unlike psilocybin or ibogaine, MDMA was not banned for over twenty years following the CSA’s enactment. A DEA emergency ban in 1985 prohibited the substance as a result of several public hearings in which hundreds of psychiatrists and psychotherapists advocated for MDMA’s potential that had been informally recorded.8 With the exception of one month between January and February of 1988, it has remained a Schedule I drug, despite promises from then DEA Office of Diversion Control head, Gene R. Haislip, of the “expedited registration procedures to assure that legitimate research into the effects of MDMA can continue uninterrupted.”9 Valid research methodology and medicinal potential were therefore sacrificed to uphold the anti-drug rhetoric of the time, setting some research decades behind.

The loss and delay of potentially groundbreaking research is probably the worst effect of the War on Drugs from a long term scientific and medical standpoint, but it is hardly the only devasting consequence. A close second in general impact and the worst from a socio-economic and equality standpoint is the disproportionate effect it had on the prosecution of minority populations by law enforcement and the exacerbation of the unfair treatment of minorities by the judicial system.

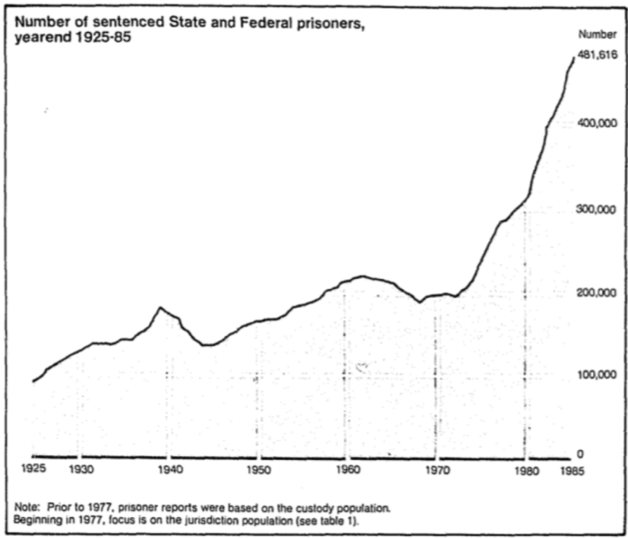

State & federal incarceration data, 1925-1985. (Figure 1)

State & federal incarceration data, 1925-1985. (Figure 1)

Since both the anti-cannabis movement of the early 1900s and Nixon’s War on Drugs demonized certain substances to unfairly target minority populations, it is hardly surprising that the same groups suffered the worst consequences of the movement’s policies. Aside from the remarks in Ehrlichman’s 1994 interview, evidence of the disproportionate prosecution of minority groups can clearly be seen upon examination of national incarceration data. Between 1925 and the early 1970s, the US male incarceration rate was relatively stable, hovering at or below roughly 200 per 100,000 population, but in the mid-1970s, the number skyrocketed (Figure 1).10

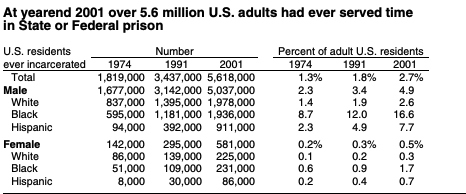

Prison demographics, 1974-2001. (Figure 2)

Prison demographics, 1974-2001. (Figure 2)

According to a later study, in 1974, the inmates made up 1.3% of the country’s adult population, but by 1991, they comprised 1.8% and in 2001, the number climbed even further to 2.7%. With that said, a closer look at the incarceration rates across differing demographics indicates that African-American and Hispanic populations were more likely to serve time in prison than their Caucasian counterparts (Figure 2).11

Recent data suggests that 2.2 million adults were in the prison system at the end of 2016; for roughly every 100,000 U.S. residents, nearly 655 were incarcerated.12 To put the number into perspective, according to estimates from the US Census Bureau, the 2016 total population of Houston, TX – the fourth most populous city in the country – was 2.3 million meaning that, if the U.S. prison population were a city, it would be the fifth-largest in the US. Incarceration rates across all crime categories from 1980-2010 increased, however, prison sentences for drug offenses specifically went from 15 per 100,000 population in 1980 to a staggering 143 per 100,000 in 2010.13 The non-profit organization Prison Policy Initiative currently estimates that 1 out of 5 inmates were sentenced for a drug offense, with arrests for drug possession making up over 5 times the number of arrests for sales and/or manufacturing.14

Analyzing the CSA Scheduling Procedures

Aside from the observation that federal officials have targeted specific groups through anti-drug legislation, a closer analysis of the logic behind CSA scheduling muddies matters further. As previously mentioned, the DEA assigns substances based on accepted medical use and potential for abuse. Examples of Schedule I drugs are heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (“LSD”), cannabis, mescaline, MDMA, and psilocybin. Schedule II substances include cocaine, methamphetamine, oxycodone, fentanyl, Adderall, and Ritalin. Perhaps one of the best examples of the illogical and capricious nature of the CSA and the DEA’s reasoning is the fact that, under the current scheduling system, the DEA has deemed cannabis to be a more dangerous and addictive substance than several of the most popular and medically-recognized-as-highly-addictive opioids that created the current opioid epidemic.

The scientific illegitimacy of CSA scheduling can be further highlighted by comparing some of the other substances in Schedule I to the opiates and amphetamines in the less restrictive Schedules. Research has found that the toxicity of LSD varies between species, however, there has never been a documented case of human death from an LSD overdose.15 The toxicity of a substance is usually established by measuring the amount of that substance that causes death in half of a test subject population that ingests the substance, usually in one “dose.” The term for this measurement is “LD50” which is an abbreviation for “lethal dose 50%. Researchers have not established the LD50 for LSD in humans. The LD50 for LSD in rats has been established at 16.5 mg/kg, and mice have been shown to tolerate doses in the 46– 60 mg/kg range.16 The important thing to note is that the effective dose of LSD in humans, the amount needed to produce psychotropic effects is measured in micrograms (mcg), or millionths of a gram, not milligrams (mg), thousandths of a gram. Threshold effects can be induced with LSD doses as low as 25mcg with doses around 400mcgs considered to be very strong.

Using the figures for rats, the LD50 for LSD for a 150 pound (~68kg) human would be 1.12 grams (over 1122000 mcg) and based off of mice tolerance, the LD50 for LSD for a 150-pound human would be between 3.13 grams (3128000mcgs) and 4.08 grams (4080000mcgs). To put that in perspective: if we conservatively assume one “dose” of LSD to be 400mcgs – already considered to be a very strong dose – a 150-pound human would have to consume somewhere between 2,800 and 10,200 “doses” of LSD to reach the LD50 for LSD, an increase of 279900% and 1019900% respectively. For a more tangible reference, it takes approximately 3 to 4 standard17 alcoholic drinks for a 150-pound human man to reach the legally defined limit of intoxication. If alcohol had the same safety profile as LSD that 150-pound man would have to consume between 1196 and 40796 standard alcoholic drinks in one sitting to achieve the LD50. The approximate LD50 for a human male is approximately 15 standard drinks.

Then there is fentanyl, an analgesic that is several hundredfolds more potent than morphine. Fentanyl is scheduled lower than LSD, despite its vastly higher potential for abuse and addiction. Deadly in minuscule amounts, the DEA estimates that fentanyl’s lethal dose for most people is just 2 mg, illustrated in the below photograph (Figure 3).18 Tragically, its abuse resulted in over 28,400 overdose deaths in 2017 alone,19 fueling the current opioid epidemic, which now stands as the deadliest overdose crisis in the nation’s history.20

Comparison of fentanyl’s lethal dose with a penny. (Figure 3)

One need not look to opiates, or even scheduled drugs in general, to see the absurdity of the system. Seemingly “safe” compounds, such as Tylenol, pose a greater risk to consumers than LSD from a toxicity standpoint.21 Acetaminophen (Tylenol is a brand of acetaminophen) is the largest cause of drug-induced acute liver failure in the US.22 Despite this, acetaminophen is readily available over-the-counter and there are no age restrictions or oversight when it comes to its purchase. Equally as illuminative – but perhaps more infuriating – is the fact that caffeine has a demonstrably more addictive profile than LSD or psilocybin.

There is some good news, international pressure to revise drug scheduling is increasing. In an assessment on the risks for harm of drugs, the Global Commission on Drug Policy’s 2019 report on the Classification of Psychoactive Substances found little evidence to support the DEA’s scheduling system. Comparing the following data on 20 substances to their corresponding CSA classification simply does not match (Figure 4).23 Neither alcohol nor tobacco is listed as a federally controlled substance, yet their reported level of harm to consumers and others is greater than most of the listed Schedule I substances. Alcohol alone presents more of a weighted score for drug risks than cannabis, ecstasy, LSD, and mushrooms combined.

The Global Commission on Drug Policy’s charted data on substances’ risk of harm. (Figure 4)

To summarize their findings, the commission wrote, “The international community must recognize the incoherence and inconsistencies in the international scheduling system and must trigger a critical review of the current models of classification of drugs.” They continued their recommendation by noting several consequences that current drug scheduling has produced, stating, “They range from the scarcity of essential medicines in low- and middle-income countries to the spread of infectious diseases and injuries, higher mortality and the global prison overcrowding crisis. The international community must face these challenges, and measure and correct the negative consequences of current schedules.”24

The second factor cited in CSA scheduling is medicinal potential or lack thereof, and Schedule I drugs are deemed to lack an approved medical use. Yet, evidence is mounting to suggest that several Schedule I psychoactive substances provide positive medical benefits. Looking first to cannabis, federal and state laws currently conflict as thirty-three states have passed legislation approving medical cannabis programs and eleven of those states permit recreational use as well.25 A recently published study out of the University of Texas found that states with medical cannabis laws reported fewer and less frequent opioid prescriptions written to patients aged 18-55. Even earlier this year, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (“MAPS”) completed the first clinical trial on the effectiveness of smoking cannabis to treat posttraumatic stress disorder (“PTSD”) and is expected to submit its findings for publication this summer.

This is wonderful news, because thanks to decades of draconian restriction we haven’t even identified, much less studied, all of the compounds in Cannabis sativa L and that has been a monumental detriment to society. Take one of these cannabinoids: cannabidiol (“CBD”), for example. In May, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai found that CBD helped curb cue-induced anxiety and cravings in patients with a previous history of heroin abuse. Similarly, last year, the FDA approved the first cannabis-derived medication, Epidiolex, to treat two rare epileptic conditions (Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gestaut syndrome). The active ingredient in Epidiolex is CBD. This one cannabinoid is drastically changing patients’ lives for the better… remember the whole “no medical benefit thing?” Try telling the parents of a child that previously had hundreds of seizures per day who can now function normally thanks to CBD that there is no medical benefit to Cannabis sativa L., and that’s just one cannabinoid! As of now, researchers have isolated over one hundred (100) unique cannabinoids and hundreds more are thought to exist. Accordingly, the moral imperative that the compounds produced by Cannabis sativa L be thoroughly investigated should be crystal clear.

This analysis does not end with cannabis though. Other psychoactive substances have reentered America’s public conscious as studies on potential medical benefits of MDMA and psilocybin continue to be published. In addition to researching cannabis, MAPS founder Rick Doblin, Ph.D., explained the organization’s dedication to the study of the clinical uses of psychedelics and empathogens, “Psychedelics are really just tools, and whether their outcomes are beneficial or harmful, depends on how they’re used.”26

Speaking at the first official TED Talk on psychedelic and psychoactive substances in April, Doblin, discussed the past, present, and future of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Through the study of PTSD’s effect on the brain, paired with clinically administered MDMA and psychotherapy sessions, Doblin claims that MDMA has the potential to encourage emotionally processing trauma, rather than current medication’s emphasis on symptom suppression. To further support his claim, this year, researchers at John Hopkins Medicine found that a single dose of MDMA has the capability to reopen the brain’s “critical period” of social reward and produces oxytocin – a hormone associated with social bonding – to aid in the improvement of prosocial behaviors.27

“Psychedelics are really just tools, and whether their outcomes are beneficial or harmful, depends on how they’re used.” – Rick Doblin, founder of MAPS

Schedule I status has made the study of MDMA incredibly difficult, and while careful research is critical, CSA scheduling impedes on the ability of qualified professionals to conduct valid clinical trials. MAPS research on MDMA began in 1986 and the organization has spent three decades gathering enough data to request FDA permission to move into Phase III of their study to prove the safety and efficacy of the proposed treatment.

Like MDMA, the legitimate study of fellow psychoactive substance, ibogaine was met with similarly exhausting delays following its entry on the list of federally controlled substances. Research pioneer, Howard Lotsof discovered ibogaine’s potential to treat heroin addicts after personal experience with the substance in the 1960s, but it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that he was able to begin research abroad in the Netherlands.28 After receiving a patent for his ibogaine treatment for heroin and cocaine addiction in 1986, Lotsof continued his work overseas until successfully gaining the attention of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (“NIDA”). “His great achievement,” Kenneth Alper, an associate professor at the New York University School of Medicine, told the New York Times, “was in inducing the National Institute on Drug Abuse to undertake a research project on ibogaine that produced scores of peer-reviewed publications and paved the way for F.D.A. approval of a clinical trial.”29 Although the FDA did approve Lotsof’s trial, lack of sufficient financing and contractual disputes prevented its completion.30

The history of the study of psilocybin is even more depressing than that of MDMA and ibogaine, as hundreds of studies on the compound were conducted prior to the CSA’s enactment that showed extremely beneficial results for a wide range of maladies. After it was placed on Schedule I, research on the substance ceased, leaving its advocates unable to amass sufficient funding for new studies until the 1990s and 2000s. In 2014, the John Hopkins Psychedelic Research Unit (“Hopkins”) was the first research team since the 1970s to use psilocybin and found evidence to suggest the substance’s potential in treating tobacco/nicotine addiction – later supported by a follow-up study in 2017. Hopkins also conducted a separate study on the benefits of psilocybin for terminally-ill cancer patients suffering from severe depression and anxiety, “with about 80% of participants continuing to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety,” at the conclusion of the study.31 Interest in psilocybin research received a boost in October of 2018 after life sciences company COMPASS Pathways announced that they had received FDA Breakthrough Therapy status – a designation permitting the expedited development and review of substances with proven levels of efficacy over existing treatments – for their psilocybin therapy on otherwise untreatable depression.32

Encouraging Social Challenges to the War on Drugs

Doblin’s presentation at TED2019 serves a cautionary note on the past studying of psychedelic substances, but also provides an optimistic glance into their future study. Assessing the previous limitations imposed on said substances, Doblin summed up the field’s current trajectory by stating, “We’re in the midst of a global renaissance of psychedelic research.”33

Doblin’s observation is accurate given recent social and academic trends to explore the potential of psychedelics, however, significant legal obstacles and hindrances continue to prevent researchers from conducting the necessary studies to determine the full effects of many substances. Although some progress has been made in the study of cannabis, MDMA, psilocybin, and their potential medicinal benefits, existing federal laws not only obstruct consumer access, but also impair institutional research. In understanding the complexity of researching psychoactive substances, it is imperative to note the sociopolitical motivators embedded in the country’s current drug policy and the resulting consequences of the War on Drugs.

Despite its existing legislative foundation and the strategies used to vilify drugs, the War on Drugs has lost its sway over public opinion over time, as indicated by cannabis’ well-known legalization movement. According to a 2018 survey conducted by the Associated Press, 61% of Americans support the legalization of cannabis, a four percent increase from a similar study held two years prior.34 Even the go-to argument against cannabis, that it’s a “gateway drug” fails in the face of real data. A study recently found that states with legal recreational cannabis legislation demonstrated lower rates of cannabis consumption in adolescents, a demographic often used to argue the dangers of repeated use.35

Thankfully cannabis and CBD are not the only substances gaining political and social traction, as voters and lawmakers both have demonstrated significant interest in other psychedelic substances as well. Early this year, Iowa Rep. Jeff Shipley proposed two bills to legalize medical psilocybin, MDMA, and ibogaine and to remove psilocybin and psilocyn from the Iowa Uniform Controlled Substances Act. Additionally, in June, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) introduced a measure to remove the CSA’s existing provision prohibiting the use of federal funds to endorse the legalization of any Schedule I substance.36

While both Rep. Shipley & Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s attempts were ultimately unsuccessful, their mere existence does indicate a growing legislative movement against the established procedures of the War on Drugs. Speaking at a town hall in late-June, Ocasio-Cortez emphasized the demonstrated potential of some federally controlled substances, stating that there are several Schedule I drugs that could help “veterans and people with PTSD and also people struggling with depression and opioid addiction.”37 Her efforts to increase access to research on psilocybin mushrooms with the possibility of limited legalization are expected to continue.

Voters have also become increasingly vocal in their hopes for future support of psychedelic substances. Residents of both Denver and Oakland have voted to approve measures to initiate the process of decriminalizing psilocybin this summer. While neither fully legalize psilocybin, both are expected to begin the process of deprioritizing the enforcement of criminal penalties for adults over 21 in possession of psilocybin.

In 2019, psilocybin mushrooms have made headlines across the country, further pressing sensible drug policy reform.

The wounds inflicted on the American populace by the continued enforcement of the core inconsistencies and flawed principles that created the War on Drugs cannot be undone. To suggest that there would be a direct means of ending it vastly oversimplifies just how deep its consequences have permeated society, however, there are ways to (legally) resist. The support of legislators and the public is important, but capital is crucial to developing and maintaining momentum key to a movement’s or initiative’s success. Looking again to cannabis as an example of progress, arguments for the legalization of the plant took on a new dimension following evidence of its economic impact. In five years, Colorado’s cannabis market has pulled in over $1 billion in tax revenue and is used to fund various youth and public health programs throughout the state.38 It is likely that in order for the pro-psilocybin and MDMA movements to succeed, their money-making potential will need to be emphasized (a pragmatic, yet rather depressing, fact when you think about it).

Recently, several organizations have emerged, making attempts to raise capital and awareness regarding psychedelics and other Schedule I substances. In early June, Business Insider reported exclusively that Canadian entrepreneurs had launched the first global, psychedelics-only venture firm.39COMPASS Pathways is currently one of the leaders in psychedelic research with their previously-detailed depression treatment using psilocybin, and biotech startup Atai is dedicated to financing related studies. Atai announced in March that it had secured the largest-ever private financing round for a biotech company, a staggering $43 million (€ 38 million) in new funding. Groups like MAPS and Schedule One Ventures have also contributed to the advocacy of psychoactive substances by supporting various studies and companies hoping to pave the way for the opportunities presented through their careful study.

The clear and consistently demonstrated medical benefits of cannabis, psychedelics, and empathogens are textbook examples of the flaws of the CSA and the failure of the War on Drugs. These substances fail to satisfy the CSA’s own criteria for placement on Schedule I, illustrating the hypocrisy endemic to the DEA and FDA and revealing the capriciousness of the system as a whole. From the Nixon Administration’s prejudices and political scheming let led to the death and the incarceration of millions of people, to the inaccurate risk evaluations of CSA scheduling – an exasperatingly ineffective anti-drug stance has deeply permeated society, causing incalculable damage. To end the War on Drugs, as a nation, it is morally imperative to reassess our understanding of psychoactive substances, confront our warped and contradictory, yet puritanical views on intoxicants, and to permit science to triumph over fear and ignorance.

- Baum, Dan. “Legalize It All: How to Win the War on Drugs.” Harper’s Magazine. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://harpers.org/archive/2016/04/legalize-it-all/

- Burnett, Malik, and Amanda Reiman. “How Did Marijuana Become Illegal in the First Place?” Drug Policy Alliance. October 8, 2014. Accessed July 11, 2019. http://www.drugpolicy.org/blog/how-did-marijuana-become-illegal-first-place

- Thompson, Matt. “The Mysterious History Of ‘Marijuana’.” NPR. July 22, 2013. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/07/14/201981025/the-mysterious-history-of-marijuana

- Thompson, Matt. “The Mysterious History Of ‘Marijuana’.”

- “Additional Statement of Harry J. Anslinger.” The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937. Accessed July 11, 2019. http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/taxact/t10a.htm

- Williams, Luke. “Human Psychedelic Research: A Historical and Sociological Analysis.” Edited by Martin Kusch. Undergraduate Thesis, Cambridge University, 1999. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://maps.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5468

- “Introduction to Ibogaine.” Ibogaine.co.uk. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://www.ibogaine.co.uk/introduction-ibogaine.htm

- Ronson, Jacqueline. “When Psychiatrists Fought Like Hell to Keep MDMA Legal.” Inverse. August 6, 2016. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.inverse.com/article/19195-mdma-1980s-court-battle-psychiatrists-versus-dea

- “U.S. WILL BAN ‘ECSTASY,’ A HALLUCINOGENIC DRUG.” The New York Times. June 01, 1985. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/01/us/us-will-ban-ecstasy-a-hallucinogenic-drug.html

- U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. State and Federal Prisoners, 1925-85. By Stephanie Minor-Harper. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 1986. 1-4.

- U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974-2001. By Thomas P. Bonczar. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2003. 1-12.

- Kann, Drew. “The US Still Incarcerates More People than Any Other Country.” CNN. April 21, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/28/us/mass-incarceration-five-key-facts/index.html

- Perry, Mark J. “The Shocking Story behind Nixon’s Declaration of a ‘War on Drugs’ on This Day in 1971 That Targeted Blacks and Anti-war Activists.” AEI. June 17, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.aei.org/publication/the-shocking-story-behind-nixons-declaration-of-a-war-on-drugs-on-this-day-in-1971-that-targeted-blacks-and-anti-war-activists/

- Sawyer, Wendy, and Peter Wagner. “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2019.” Prison Policy Initiative. March 19, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2019.html

- Passie, Torsten, John H. Halpern, Dirk O. Stichtenoth, Hinderk M. Emrich, and Annelie Hintzen. “The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review.” CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 14, no. 4 (2008): 295-314. doi:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x.

- Passie, Torsten, John H. Halpern, Dirk O. Stichtenoth, Hinderk M. Emrich, and Annelie Hintzen. “The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review.”

- In the USA “standard” means 14 grams of ethanol regardless of the type of drink. This equates to roughly 12 fluid ounces of beer, 5 fluid ounces of wine and 1.5 fluid ounces of distilled liquor which is usually about 40% alcohol by volume.

- DEA. “Fentanyl.” United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Accessed July 31, 2019. https://www.dea.gov/galleries/drug-images/fentanyl

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Overdose Death Rates.” NIH. January 29, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- Lopez, German. “Study: If a Family Member Is Prescribed Opioids, You Have a Higher Risk of Overdose.” Vox. July 09, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/7/9/20681490/opioid-epidemic-prescription-painkillers-overdoses-study.

- This statement is based on the toxicity of the compound in question and the pharmacologic effect on the human body, it does not take into account the chance of people accidentally injuring themselves due to the psychotropic effects of LSD.

- Oleszczuk, Zachary. “Pharmacists Can Help Reduce Risk from Extended-Release Acetaminophen — A Key Potential Confounding Factor in Suspected Overdoses.” Pharmacy Times. July 15, 2019. Accessed July 18, 2019. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/news/pharmacists-can-help-reduce-risk-from-extendedrelease-acetaminophen–a-key-potential-confounding-factor-in-suspected-overdoses.

- The Global Commission on Drug Policy. Classification of Psychoactive Substances. Report. July 3, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019. http://fileserver.idpc.net/library/2019Report_EN_web.pdf

- The Global Commission on Drug Policy. Classification of Psychoactive Substances.

- “Teen Odds of Using Marijuana Dip When States Legalize Recreational Use.” NBCNews. July 8, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/kids-health/teen-odds-using-marijuana-dip-when-states-legalize-recreational-use-n1027576.

- Doblin, Rick. “The Future of Psychedelic-assisted Psychotherapy.” TED. April 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.ted.com/talks/rick_doblin_the_future_of_psychedelic_assisted_psychotherapy.

- Nardou, Romain, Eastman M. Lewis, Rebecca Rothhaas, Ran Xu, Aimei Yang, Edward Boyden, and Gül Dölen. “Oxytocin-dependent Reopening of a Social Reward Learning Critical Period with MDMA.” Nature 569 (April 3, 2019): 116-20. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1075-9#article-info

- Hevesi, Dennis. “Howard Lotsof Dies at 66; Saw Drug Cure in a Plant.” The New York Times. February 17, 2010. Accessed July 19, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/17/us/17lotsof.html.

- Hevesi, Dennis. “Howard Lotsof Dies at 66; Saw Drug Cure in a Plant.”

- Ibid.

- Griffiths, Roland R., Matthew W. Johnson, Michael A. Carducci, Annie Umbricht, William A. Richards, Brian D. Richards, Mary P. Cosimano, and Margaret A. Klinedinst. “Psilocybin Produces Substantial and Sustained Decreases in Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Life-threatening Cancer: A Randomized Double-blind Trial.” Journal of Psychopharmacology 30, no. 12 (December 01, 2016): 1181-197. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0269881116675513.

- COMPASS Pathways. “COMPASS Pathways Receives FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for Psilocybin Therapy for Treatment-resistant Depression.” News release, October 23, 2018. PRNewswire. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/compass-pathways-receives-fda-breakthrough-therapy-designation-for-psilocybin-therapy-for-treatment-resistant-depression-834088100.html

- Doblin, Rick. “The Future of Psychedelic-assisted Psychotherapy.”

- Blood, Michael R. “Poll: Support Rises in All Age Groups for Legal Pot.” AP NEWS. March 19, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.apnews.com/8eb58810be2642b3a2c81e9da247ff80.

- Anderson DM, Hansen B, Rees DI, Sabia JJ. “Association of Marijuana Laws With Teen Marijuana Use: New Estimates From the Youth Risk Behavior Surveys.” JAMA Pediatrics. Published online July 08, 2019. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1720

- Angell, Tom. “AOC Pushes To Make It Easier To Study Shrooms And Other Psychedelic Drugs.” Forbes. June 08, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tomangell/2019/06/08/aoc-pushes-to-make-it-easier-to-study-shrooms-and-other-psychedelic-drugs/#69e36d351002

- Levine, Jon, and Ben Cohn. “‘We’re Not Giving up on This’: AOC Touts Plan to Research Medicinal Use of Magic Mushrooms.” New York Post. June 29, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://nypost.com/2019/06/29/were-not-giving-up-on-this-aoc-touts-plan-to-research-medicinal-use-of-magic-mushrooms/

- Julig, Carina. “Colorado Surpasses $1 Billion in Marijuana Tax Revenue.” The Denver Post. June 12, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.denverpost.com/2019/06/12/colorado-marijuana-revenue-one-billion/

- Berke, Jeremy. “Investors Just Launched the First VC Dedicated Exclusively to Psychedelics, Which They Call the ‘next Wave’ after the Cannabis Boom.” Business Insider. June 13, 2019. Accessed July 11, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.com/first-vc-psychedelics-field-trip-ventures-canada-2019-6?_ga=2.261122189.182982476.1562862206-1277395604.1562862206.

The information in this blog post (the "Blog" or "Post") is provided as news and/or commentary for general informational purposes only. The information herein does not, and shall never, constitute legal advice and therefore cannot be relied upon as a legal opinion. Nothing in this Blog constitutes attorney communication and is not privileged information. Nothing in the Post or on this website creates any kind of attorney-client relationship or privilege of any kind.

Congratulations @rodmanlaw! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPTo support your work, I also upvoted your post!

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!