Philosophy of Science Part 2: Occam's Razor is Rusty

I don't mean that Occam's Razor is just a little rusty- you pose a real risk of getting tetanus if you use it. For those unfamiliar with Occam's Razor, it's a proposition that states, in its most common form, that the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. And, not to dance around the topic, I can't stand the Razor.

William of Ockham, the English friar and philosopher (c 1287-1347) who the Razor is named after. His formulation of the idea was Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate (Plurality must never be posited without necessity). [Image source]

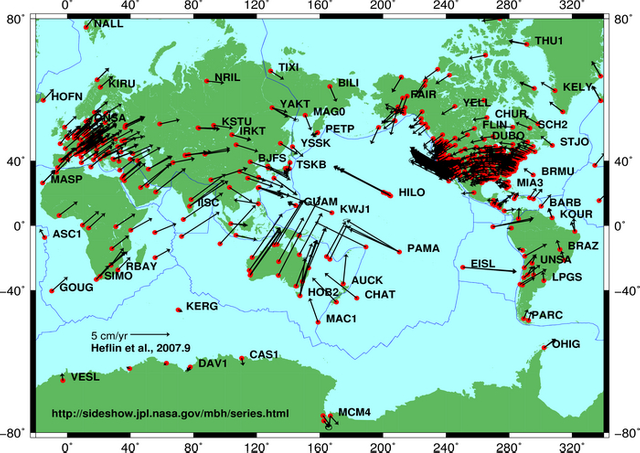

In its most popular form, the Razor is easy to lampoon. Plate tectonics is immensely more complex of an idea than its earlier alternatives, and yet it is, so far as we can tell, the correct answer. I can name literally dozens of other situations in which this is the case. This, however, is somewhat of a strawman attack upon the Razor- it can, and often is, phrased much more intelligibly than the popular version of it. A version of it with a stronger foundation is that "when presented with competing hypothetical answers to a problem, one should select the answer that makes the fewest assumptions." (Wikipedia's definition.) This clearly and apparently is more capable of withstanding a basic assault than the popular version.

Nonetheless, I still don't count myself a fan. There are a few reasons for that. One of them is the frequent interpretation of the history of science through its lens. Take the case of Copernicus, champion of the heliocentric (sun-centered), model of the solar system. Advocates of Occam's razor often point to the success of his model of the solar system over the older geocentric (Earth-centered) model of the solar system as a proving ground of the Razor. According to them, the geocentric model was by far the more complex one, requiring unnecessarily complex mathematical constructs called epicycles, extra little circular orbits tacked onto the main orbits. It's true that the geocentric model possessed epicycles, but guess what? So did the Copernican heliocentric model. In fact, it required 34 of them to function! This was because Copernicus predicted circular orbits for the planets, rather than elliptical ones. We don't know precisely how many epicycles the prior geocentric model used precisely, but there's no real evidence indicating that it used particularly more epicycles- nor, frankly, is the number of epicycles a greater complication than the sheer fact of their presence.

Nicolaus Copernicus, pioneer of the heliocentric model of the universe. [Image source]

Not only was Copernicus' explanation not simpler, but his detractors weren't actually doing bad science for the time. Their conclusions might have been incorrect by today's understanding, but they were actually doing their best to understand the universe using the evidence they had available to them. This is exemplified in the battles of Galileo Galilei, the heir to Copernicus' heliocentric torch. There's a common narrative that Galileo's main opponents were religious zealots in the Catholic Church, offended because he was defying what the Bible said. In actuality, however, his fiercest opponents were other astronomers, who rejected the heliocentric idea for strictly scientific reasons. (Specifically, the lack of an observed stellar parallax.) The whole Galileo getting house arrest for the latter part of his life thing? Well, his opponents basically sicced the Inquisition on him (science was really cutthroat back then). The Pope and the Jesuits, however, defended Galileo for years, only withdrawing their support when one of his books appeared to trash talk the Pope. Interestingly, Galileo rejected Kepler's heliocentric solution, which actually used ellipses and eliminated epicycles.

We could spend a whole book (and indeed many have) on the complex and weird nature of the Galileo situation, but getting back on topic, it's hardly the only example of the failure of even the better phrased version of Occam's Razor to explain events in the history of science. The rise of plate tectonics as a theory is, again, great to bring up. Not only is it not particularly simpler than its predecessors (though I should note that its predecessors tend to be far, far from simple- pre-tectonic explanations for mountain ranges were hellishly weird and complex at times), its adoption did, in fact, require the adoption of a huge amount of new assumptions, as seen by its opponents at the time. This is, in fact, a fairly common criticism of new scientific hypotheses. All scientific theories and hypotheses rest on a certain amount of assumptions, and for established theories, those assumptions tend to be pretty well supported. (The universe operates under the same laws of physics day-to-day is one pretty big assumption we all rely on, for instance.) New hypothesi, whether they're vindicated in the end or not, tend to rest on a great number of assumptions that have less support than the previously existing theories.

A map of Earth's known tectonic plates and their directions of movement. [Image source]

In fact, there's no point in the history of science that we can look at a battle between two rival theories and say that one won over the other thanks to it being the simpler one. Instead, the winner is the one that has more and better evidence backing its various assumptions and claims, as well as more accurate predictions- regardless of how many of each there are. Often, the number of claims that a hypothesis makes is enormous- but if they can all be backed with evidence, that can often lead it to victory against a simpler, more elegant answer. In this sense, Occam's Razor can be somewhat criticized as telling us to do less work to prove our ideas. That's clearly not an intended claim of the vast majority of its advocates and users, but it is an odd logical consequence of it.

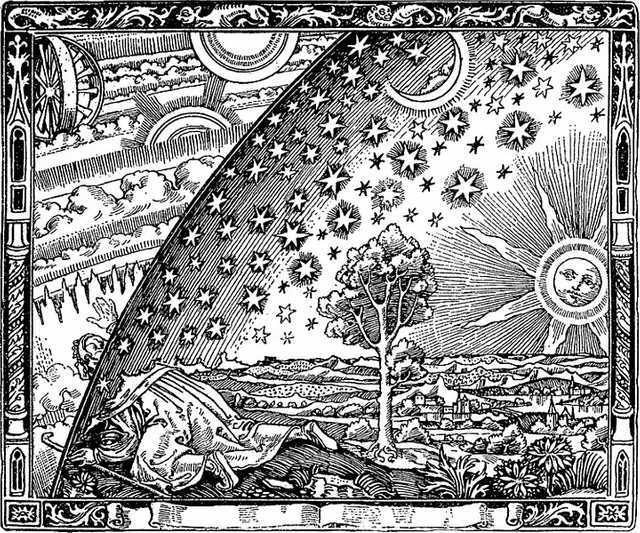

Occam's Razor in the context of the history of science plays a very specific ideological role- that of reinforcing the image of us advancing from ignorance to enlightenment. While this is a true image in many senses, it has proceeded to the point of demonizing past theories as absurd, ignorant, and superstitious, along with their advocates. There's a lot of quite deliberate reasons to do so- they often are in place for the purpose of attacking religion. The idea that medieval people believed the Earth was flat, for example, was one of those. They very much didn't- they'd known the Earth was round since ancient Greek times. There are, in fact, only one or two references to a flat Earth we've found in medieval documents at all. This whole idea arose as propaganda during the Reformation, when Catholics and Protestants regularly began hurling it as an insult- only a fool would believe the Earth was flat, so if the other side believed that, then they were fools! It was then adopted and treated as true by a number of historians unfriendly to religion in the late 1800s, and has been passed down to a great number of people today, like the angry atheist movement. It's also become part of the mythology around Christopher Columbus, that he knew the Earth was round when his opponents doubted it. Actually, everyone involved knew the Earth was round, Columbus just thought the Earth was way smaller than everyone else, and they were worried he'd die in a giant empty ocean from lack of food and water before he reached Asia. Unfortunately, this narrative of medieval people thinking the Earth is flat has also been used as evidence that the Earth actually is flat by Flat Earthers, which is ironic on quite a few levels.

Depictions of a flat earth under a literal dome of stars, like the Flammarion Engraving depicted here (unknown artist) are fairly common in Medieval Europe. They seem, however, to be merely a common and stylish artistic embellishment from the time period. And, honestly, they do look really cool. Texts from the time that discuss the shape of the world essentially universally consider it round, however, so illustrations like this or the exterior of Heironymus Bosch's Garden of Earthly Delights must be considered fanciful. (Which should be clear to anyone who has ever looked at a Bosch painting for more than a couple of seconds.) [Image source]

The historical is far from the only level on which I dislike Occam's Razor, however. More importantly, any effort to simplify science makes me immediately suspicious. The world is messy, difficult, and problematic, and so is science. Efforts to use Occam's Razor to cut the world down to an elegant core of truth end up making that core untrue by forcing so many lies of omission onto it- all those weird, messy bits the Razor is cutting off? Those are as integral to the truth as the shiny bits at the center. Of course, some simplification is ultimately necessary- a scientific theory which tries to be just as complex as the world it describes would be unwieldy to the point of uselessness. It's a difficult and important balancing act between the accuracy of a theory and it having enough simplicity to be useful. Generally, though, I'm going to advocate for more complexity in our understanding rather than less.

There's also the genuine risk that using Occam's Razor can cause real damage. There's an idea called Hickam's Dictum in medicine that exists in direct conflict to Occam's Razor. While Occam's Razor might cause a doctor to look for the simplest explanation for a patient's symptoms, Hickam's Dictum states that "A man can have as many diseases as he damn well pleases." This goes fairly well for research science as well- anthropogenic climate change, for example, isn't caused merely by car exhaust, or coal plants- instead it's caused by those, and by construction emissions, and by cow farts, and by our destruction of natural carbon sequestration processes, and by a long, long list of other factors. It's far from a simple explanation, but it is by far the best one we have.

All that being said, please, please don't take this as me telling you to favor more complicated scientific theories or to disdain simpler ones. I want to make it very clear that you should favor the theories best supported by empirical evidence and testing. And, in fact, the basic idea of not getting too crazy with the number of assumptions isn't really a bad one- Occam's Razor may be safely used if you polish off the rust a bit. Which is to say, if used as a heuristic or loose guideline, it won't do too much damage. You've just got to remember that often the right answer will require you to extend- and then support with evidence- a huge number of assumptions. To the credit of most scientists (with some prominent and unfortunate exceptions), they seem to understand this quite well, and happily abandon simple theories for more complex ones when needed. Like so many philosophy of science debates and arguments, this one is often most relevant outside the immediate practice of solving scientific problems. Learning when and (more often) when not to use Occam's Razor is just part of learning to be a scientist.

“The aim of science is to seek the simplest explanation of complex facts. We are apt to fall into the error of thinking that the facts are simple because simplicity is the goal of our quest. The guiding motto in the life of every natural philosopher should be “Seek simplicity and distrust it.” – Alfred North Whitehead

Bibliography:

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn

- https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/08/occams-razor/495332/

- http://scienceblogs.com/developingintelligence/2007/05/14/why-the-simplest-theory-is-alm/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hickam%27s_dictum

- https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/fpRN5bg5asJDZTaCj/against-occam-s-razor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occam%27s_razor

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolaus_Copernicus

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_tectonics

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myth_of_the_flat_Earth

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Garden_of_Earthly_Delights

Commento “Post of the day”

Hi @mountainwashere

We have selected your post as post of the day for our DaVinci Times. Our goal is to help the scientific community of Steemit, and even if our vote is still small we hope to grow in quickly! You will soon receive our sincere upvote! If you are interested in science follow us sto learn more about our project.

Immagine CC0 Creative Commons, si ringrazia @mrazura per il logo ITASTEM.

CLICK HERE AND VOTE FOR DAVINCI.WITNESS

Keep in mind that for organizational reasons it’s necessary to use the “steemstem” and “davinci-times” tags to be voted again.

Greetings from @davinci.witness and the itaSTEM team.

Guess what? I will make a connection between your post and particle physics.

In particle physics, we really like minimality and simplicity. This is always the first thing we try when we want to describe some phenomenon. However, sometimes simplicity is challenged by data. We then move to next-to-minimality, and so on. We enjoy simplicity a lot, but we are scientists before anything else: we can admit simplicity sometimes does not work :)

Oooh, I really like that, that's a good one!

You know, I've always thought of geology and physics as being somewhat... not in opposition to one another, necessarily, but on opposite poles of the scientific spectrum. Physics is the 'purest' science, while geology is by far the least pure science- it's applied physics, applied math, applied chemistry, applied biology, so on and so forth. Physics is also farthest to the experimental/predictive side of the experimental/predictive-descriptive/interpretive dichotomy of science, while geology is arguably farthest to the other. So when you get physicists and geologists agreeing on scientific methodology, it's probably best to listen. :D

The methodology, the scientific method, is common to all fields. Or at least it should be :)

Ideally, but when you're studying a rock outcrop formed millions of years ago, you're basically in a situation where the experiment was already run without you there, and you have to puzzle out what the variables and such were after the fact.

I maintain that the methods that will be used to get some conclusive statements till follow a scientific approach.

I don't disagree, I just think there's a lot of flexibility in the scientific approach.

Which I agree with as well (this was implicit in my messages) :)

hahaha it is funny to read you both... I am neither, thank God (studying to become an Internationalist), but physics does indeed have to stick to the minimal movements, while geologists, if they want to be useful, need to look beyond the little limitations... to go beyond the razor :D

in other words, geographical ones, it is fine and simple to say that human regions of the world can define "continents": we have Asia, Europe, America as as whole... but if we go beneath the surface, beyond the razor, we find Eurasia has no borderlines for Asia and Europe, and instead "America" (as they teach us in Spanish), are absolutely un-joinable landmasses: North America and South America... Occam would stand on the first point of view, while Galilei would (rightfully so) stand on the second one, the physical one, which after all does define humanity's comings and goings...

Physics needs sometime to be non-minimal. We always try the minimal way first, but sometimes this just does not work.

Another consideration regarding Occam is that his method was a critique of an opposing theological argument regarding existence of God, a metaphysical and may be philosophical context, rather than method used for physics, or science. Though Occam's method may have utility in physics/science sphere, to use his method primarily in physics would be to turn physics into metaphysical exercise.

It's hard to separate science from theology during those years- or even up well through the Renaissance. Many of the early scientists used extensive metaphysical rather than empirical methods. So while it absolutely does turn physics into metaphysics, it's only recently that many scientists wouldn't think that to be fine, or even the goal. (As I mentioned to another commenter, separating the early history of science from religion and religious thought is an impossible task.)

Can't wait for your next post, by the way!

Like @lemouth implied in his comment here, my impression was that Occam's Razor was best applied and witnessed working in math and physics. In other sciences, it's kind of a mess.

When there's evidence that cow farts cause climate change, cow farts should be included in the theory. The fact always takes precedence. It's only when comparing theories whose only difference is their simplicity/complexity that the simplest theory ought to be preferred. In Occam's original formulation, there's little to disagree with, if anything.

I liked what you did in putting the historical record straight. I often wonder where all these ahistorical over-simplifications - almost myths and wive's tales - originated from.

An interesting coincidence, just today I was reading a paper that contained the following snippet:

Hah, that's a great little snippet! Anything that trash talks B.F. Skinner that elegantly is cool in my book, too.

I am a big fan of not unnecessarily overcomplicating things, but I have also encountered scientific research that wants to simplify things too much. Usually by attributing too many observations towards the same processes. This goes hand in hand with the issues that uniformitarianism presents. I know you have your thoughts towards that topic as well.

I really like the background information you present here.

The story of shit-talking christians was new to me. Nice fun fact.

Oh, dude, the history of science is inextricably bound up in the history of religion, and trying to understand science from a time period without understanding the theology it existed alongside is fruitless- one of the main reasons I dislike the angry atheist stuff so much.

I clearly have some reading to do...

Can you suggest any starting points?

Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle, by Stephen Jay Gould.

Took me a while, but I finally made my way to the library. Can't wait to dive into it on the weekend. Another wonderful way to procrastinate on my blog 😜

Heck yeah, hope you enjoy it/ find it useful!

Thanks 😃

I would suggest Wikipedia actually... the articles about the church, really...

First, about the primitive church, with Peter and Paul and the meetings in catacombs; then, the proclamation of Christianity by Constantine as official and the rise of Catholicism... Then, the Great Schism of circa year 1,000 (separation into Orthodox East and Roman Catholic West); after that, come exciting times: the Protestant Reformation, the Counter-Reformation in Spain and the South of Europe, and also the end of the Byzantine Empire and the rise of the Ottoman one...

LOL i don't think he actually meant it like that... the Catholic Church was against saying the Earth was not flat because they thought it was in the Bible... but Protestants knew better; they were, are and have always been more progressive and advanced than old fashioned catholic nuns with big top hats and golden palaces...

Lovely article, I enjoyed it, for the most part... I need to go deeper into it, but the part about Copernicus and Galilei was spectacular... Occam's razor is a myth then... but it is still used in some contexts

at any rate, great discoveries do deny the applications the razor has, which kind of render it useless... what would you call the opposite theory?

Copernicus' Sun?

Galilei's Last Stand?

Colombus' Stubbornness?

xD

Hah, I'm not sure it has an opposite, but those are clever names for it if there was!

Hello @mountainwashere

Mastering what you referred to as Occam's Razor is very important in presenting scientific findings in order to make them appealing and easy to understand. I really like how you used that phrase in this discourse.

Science is a complex field and when scientists make their findings complex, difficulty is created and everyone is lost about the essence of the whole findings. Hence, simplicity should be the major philosophy of science.

Regards,

@eurogee of @euronation and @steemstem communities

Glad to see people like you in this community, but above all I am impressed your effort for this great work, thank you for promoting science through education. I have learned so much with your class today. God bless you and fill you with success, always.

Regards...

Congratulations! This post has been chosen as one of the daily Whistle Stops for The STEEM Engine!

You can see your post's place along the track here: The Daily Whistle Stops, Issue #154 (6/3/18)

The STEEM Engine is an initiative dedicated to promoting meaningful engagement across Steemit. Find out more about us and join us today.