The Great Indian Famine of 1876-78: Land Use and Social Policy in Colonial India

Queen Victoria and Benjamin Disraeli, in a nineteenth-century drawing. This may have been the occasion of Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Victoria was crowned Empress of India during Disraeli's tenure. Celebrations were held in Delhi (1877) in the midst of the 1876-1878 Famine.

Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), who was Prime Minister of Britain from 1874-1880, is said to have referred to India as the "brightest jewel in the crown" of the British Empire. Disraeli made the statement with good reason. Of all the colonies over which England held dominion, India was its most profitable. This profit to Britain came at great cost to India, however. It was extracted from the colony with unrestrained pragmatism. Every policy imposed upon India by the British had one goal: to increase revenue. This increase was to be realized through commerce and taxation.

In order to give a true impression of Britain's relationship with colonial India, it would be enlightening to focus on one historic event: the Great Indian Famine of 1876-1878. While some apologists in Britain, and some historians, characterized this calamity as a natural, inevitable result of drought, the famine was not that, although drought was a precipitating factor. There were other causes, long-term and underlying, which were abetted by British colonial policy. British management of the disaster, once it occurred, amplified the famine's toll.

The story of the famine encapsulates Britain's legacy of colonial rule in India.

The painting shows an employee of the British East India Company arriving in Calcutta, 1803. The painting is by William Prinsep and is in the public domain.

The Famine

There are disagreements about different aspects of the famine--its cause, the extent of mortality, the role of disease, and the effectiveness of government response. One point about which there is no disagreement, however, is that a calamity of biblical proportion befell the people of Southern India between 1876 and 1878. While these years are accepted as the defining period of famine, they are merely dates of convenience. People starved before and after this set period.

In Demography of Indian Famines: A Historical Perspective, Arup Maharatna explains that famine is not easily defined. It is a complex phenomenon in which the scarcity of food has widespread socioeconomic effects, including: migration, family disruption, disease and crime. Although a great number of deaths during a famine may be directly attributable to starvation, deaths from disease may also be indirectly attributed to food shortage. People who are undernourished have compromised immune systems and therefore are more susceptible to disease. Exposure to disease increases as the hungry leave their homes and migrate to new areas in search of food.

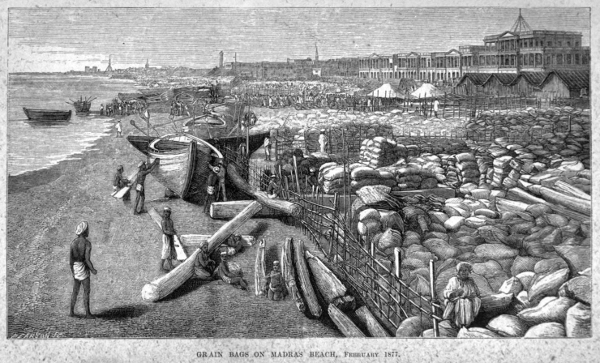

Grain stacked on a beach in Madras, waiting for export, 1877. The drawing is from a book by William Digby, who was witness to the famine and who was editor of the "Madras Times" in 1877. This is a public domain image.

Estimates of the magnitude of mortality during the famine vary. Generally, a figure of 5.5 million is accepted, but some legitimate sources suggest a much higher toll. Emeritus Professor of Geography at Indiana University, William Dando, for example, suggests a more accurate mortality count may be between 6.1 and 10.3 million, if neighboring princely states are included ("Food and Famine in the 21st Century, by William Dando").

There is little doubt that poor institutional response to the famine contributed to the misery. As with every crisis, there's a circle of blame, with fingers pointed in many direction. One reason it is convenient to deflect blame is that responsibility for famine relief was not unified: in the princely states (having autonomy but owing tribute to Britain) of Hyderabad and Mysore, local governments had control, and in British territory the response fell on British administrators. These administrators included Sir Richard Temple, Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal and Lord Lytton (Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Earl of Lytton), Viceroy of India. History generally indicts these two men for their apparent indifference to suffering, and for actions they took which actually increased suffering. Some of these actions were:

- During the height of the famine, 320,000 tons of grain were exported from India, away from famine-stricken areas. Lytton was responsible for overseeing this diversion of grain. He insisted that "free-market" principles should prevail.

- Temple, as Famine Commissioner, strengthened the rules that limited relief disbursements.

- Temple, who oversaw labor camps that disbursed relief, reduced the daily food allowance for workers. He was concerned about creating a culture of "dependency".

- Temple made it illegal in the state of Madras to give charitable donations if these would in anyway disrupt the price of grain on the open market.

- Lytton insisted that revenue collection (taxes) be maintained at customary rates, despite the inability of the people to pay.

Origins of the Famine

There was no single cause of the famine, although a severe drought and subsequent crop failure were the precipitating events. A combination of underlying factors came together to create the calamity of 1876-1878. These factors were social, political, economic and ecological in nature. To understand the interrelationship of these elements, and their connection to the famine, it is necessary to understand how British rule began in India. From the start, this was a commercial relationship. A business, The British East India Company, took control of Bengal in 1757. The company, chartered by the British Crown, proceeded to extract as much profit as possible from the land and the people. Everything that ensued from British rule makes sense when viewed from this profit-incentive perspective. Even the famine, and the government response to it, make a sort of amoral, utilitarian sense when viewed from this starting point.

Lord Clive meeting with Mir Jafar at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. It was this battle that gave the British East India Company a foothold in India. Clive was fighting on behalf of the Company. This image is in the public domain.

Two areas of concern addressed by the Company were land organization and revenue collection. This bifurcated focus would come to characterize the relationship of Britain to its colony until the end of colonial rule. Private investors were to profit and the Crown was to maximize tax revenue. In this philosophical perspective, Lytton's insistence on supporting grain prices and collecting tax revenue is logically consistent with Britain's mission in the colony.

The Company altered the people's relationship to land and transformed land use. In doing so, the East India Company unwittingly laid the groundwork for the Famine of 1876-78.

In 1793 a land reform act was passed. Called the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, the measure was the brainchild of Lord Cornwallis (yes, the same Cornwallis who had surrendered to George Washington at Yorktown). In the Settlement Act, the traditional relationship of cultivator to land was redefined. Intermediaries were appointed, in perpetuity, to oversee tax collection from the cultivators. These overseers were essentially absentee landlords. The rate of taxation they were assessed by the East India Company was fixed, and high. If the overseers failed to turn in the assessed revenue, the land they had been assigned would be auctioned off.

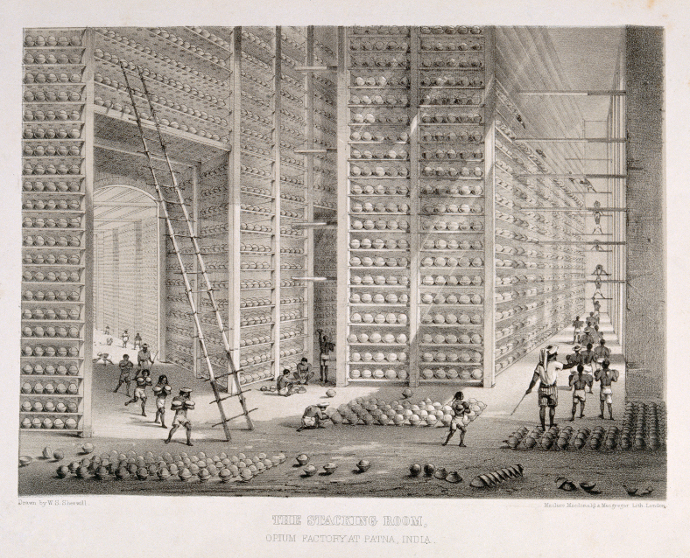

This picture shows an opium stacking room in India. Vast plantations of the cash crop were cultivated. The British trade in opium replaced the Dutch, who had been selling opium to China since about 1700. The picture comes from the Wellcome Trust and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

According to the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, many landlords could not pay the assessed tax, so their land was confiscated and auctioned on the open market. The cultivators, who were pressured by the landlords, could not meet these demands. Many small cultivators became landless. A class of moneylenders and bankers grew up to meet the new demand for cash. Property, for the first time in India's history, was commercialized. The pressure to produce cash crops, rather than food crops, grew. This meant much food-producing acreage was lost to the demands of the new commercialism. Demands on the soil were so great that nutrients did not have time to replenish.

The desire to maximize profit led to clearing of wilderness lands to make room for large plantations. There indigo, cotton, opium and tea could be cultivated. Forests were cleared. Railroads were constructed through virgin territory to transport products and people. Trees from the forests were used to build the railroads. Irrigation canals, once again through wilderness lands, were excavated to enable plantation development.

Food crops that were grown were often not for domestic consumption, but for export, because this is where profits could be reaped. As an aside, I should mention here that the opium was wreaking havoc on the Chinese people and on its military. The emperor of China was powerless to stop the trade.

A significant effect of land commercialization was that no food stores were set aside for hard times. Traditionally, small-scale cultivators would put away a portion of what was produced. This would be available to them during drought or other difficulties. Cash crops did not allow for reserves, so that when drought or other adverse conditions hit, there was nothing to fall back on. Any surplus was sold, not returned to the people. As Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen explained, a famine does not result from a shortage of food, but rather from the inability of some people to get food. See his quote here.

Cotton

One plantation crop deserves special mention: cotton. The growth of cotton in colonial India cannot be considered in isolation. The British perspective on this crop was a function of the industrial revolution and the need of manufacturers in England to have cheap raw materials. It was also a function of the industrial revolution in that once British factories had woven fabric, they needed a market to which they could sell it. So cotton, in the form or fabric, was sold back at a profit to the very people who had grown it. Not only did this process drain resources from India, but it destroyed the indigenous textile industry in the colony.

Britain's need for cheap cotton was great. Much of it was obtained from the United States, which had plenty of cheap cotton because of free labor (slaves). When the Civil War broke out in the US, the cotton flow from that country was interrupted. An effort was made to compensate for the loss by increasing cotton production in India. A US strain of cotton was introduced by enterprising British botanists. Unfortunately, their experiment did not work. In a few years it turned out that Indian soil was depleted by the American strain. Moreover, the strain did not flourish in dry spells. Native species, with longer roots that could reach deep water sources, were more suited to the ecology and climate of India.

Deforestation

The plantations, irrigation canals and railroads necessitated the clearing of wilderness lands. This resulted in a warming and drying of local climate. As explained by Vijay Joshi, a former director of the Geological Survey of India, forests influence precipitation and collect carbon dioxide. Thick forestation may increase precipitation in an area by as much as 20%. Michael Mann, of Penn State University, describes the warming, and drying of deforested areas of India after the 1830s.

A railway bridge built by the British in 1867 in Kerala, India. The picture is in the public domain.

Irrigation

To facilitate cultivation on plantations, extensive irrigation was required. Irrigation canals were dug in what had formerly been wilderness areas. Allowance was not made for water drainage. Labor was imported to dig the trenches. One result was malaria outbreaks. Another was loss of forest cover, and the consequent effect on climate.

Extensive irrigation, by itself, can disrupt local precipitation patterns and temperature. According to a report from a group of MIT researchers, extensive irrigation affects rainfall. Another study, published in the International Journal of Climatology, looked specifically at irrigation and its effect on monsoon. This study showed a decrease in monsoon in heavily irrigated areas.

Preceding and during the Famine of 1876-78, there was a failure of monsoon. A sense of doom fell upon people as the rains did not come. The ensuing drought may have occurred in any event, without the various disruptions in land use, but those disruptions certainly did not help to mitigate the severity or social consequences of the drought.

Voices of Protest During the Famine

There were voices of protest during the famine, British voices. Two men who argued for more humane policies were William Robert Cornish and William Digby. Cornish was Sanitary Commissioner of Madras at the time. He argued that increased rations should be given to workers in the relief program. He had previously served as medical officer at a large jail in a southern Indian province, where he learned about the nutritional requirements of inmates. He increased inmate rations when he noted a high death rate and realized this was due to malnutrition. The experience with nutrition in jails helped to inform his decisions during the famine.

Another notable advocate for famine relief was William Digby, a journalist. Digby was editor of the Madras Times during the famine. What he witnessed made him a critic of British colonial rule in India. His book, "Famine Campaign in Southern India", provided an eyewitness account of the suffering of the people, and of the poor government response. Digby returned to England, eventually, but continued to work for reform in colonial India.

The Seeds for Independence are Sown

In 1885 the Indian National Congress was founded. At first, the INC was viewed favorably by the British. The organization was seen as a bridge between the colonial administration and leaders of the Indian community who wanted change. Over time, the focus of the INC leaders shifted toward the Independence Movement. One persuasive voice in this shift would be Mohandas K. Gandhi.

In 1947, India became an independent nation.

Chittaranjan Das (1869-1925), an early leader of the Independence Movement in India. He served as President of the Indian National Congress, but turned leadership over to Gandhi in 1921. The two men joined together in working for India's independence. This picture is in the public domain.

I would upvote, but too late now.

Thanks for reading that.

Thanks for writing it.

You received a 60.0% upvote since you are a member of geopolis and wrote in the category of "geopolis".

To read more about us and what we do, click here.

https://steemit.com/geopolis/@geopolis/geopolis-the-community-for-global-sciences-update-4

That guy sure got around, didn't he?

And he made a mess everywhere he went...:))

Congratulations @agmoore! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

To support your work, I also upvoted your post!

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPNice!!! It wasn't me this time.

Thank you. Hard work...I learned a lot about land use :)

Ha ha. I'm the guilty party this time. I am sorry I didn't comment when I submitted the article as I was in a rush to get on discord to a curation show I was speaking at. I really enjoyed this post @agmoore, it was so in-depth about a subject I knew a little about but not enough. I learned a lot from reading this post and that's why I submitted it regardless of you getting a curie a few weeks back. This was an excellent educational post and well deserved of the curie vote :-)

Thank you, for the recommendation and the high praise. I had written a small book about Rabindranath Tagore for elementary school children. Then I wrote another small book about the British Empire, so I knew a little about the subject. But all that stuff about land use, that's self-education. And I love it.

Thanks again. I'm having a great day.

It really wasn't me this time. Another @curie curator submitted it. I considered it, but I thought your last one had been sooner for some reason. I am glad other curators have their eye on you too. You are an exceptional writer. It is so hard for newer good people to get attention. Hopefully, the boost will help you get some new followers.

Just so you know, @curie is currently having a 'My Curie Story,' campaign to help spread awareness about their cause. Anyone is free to write about how @curie has impacted them on steemit. If you would like to share a story it would be greatly appreciated. I am currently working on one.

Also, @curie has a witness node here on steemit. Our witness recently dropped from the top 20 and their income has drastically reduced as a consequence. This is affecting the organizations ability to employ more curators and curate more posts. Besides spreading the word with your story, you could also help by voting @curie for witness by clicking here: https://steemconnect.com/sign/account-witness-vote?witness=curie&approve=1

In the event you don't know about @curie you can visit the @curie page or join the chat on discord to learn more... https://discord.gg/NTXghxf

I voted for @curie already. After they supported my blog I was very grateful. I think it's a good organization--good for bloggers, good for Steemit. I will write a story, because you suggest it. The biggest surprise for me, on Steemit, is how generous some people can be, with no expectation of payback--like you.

There seem to be two universes operating here, one with community that fosters content and cooperation, and then THE BOTS. It's easy to look past the bots. I don't understand them too well anyway. So much other good stuff.

As for being an exceptional writer--I go over and over everything. It's more effort, and determination, than talent.

I'll think about that story and help @curie in any way I can. Thanks for the encouragement. It's made a difference.

Likewise. You were one of my early 'followers,' and have always been supportive and willing to engage. The human element makes a big difference. I actually initially became a prospective curator on curie specifically to propose your Fig and Wasp post. We need more people like you on here.

I follow talent--and nice people. Sometimes either or, but in your case, both. I'm not good at self-promoting--you did the job for me.

Thank you.

Very informative. Thanks.

Thank you!

Amazing post! I love it. Hey UPVOTE my post: https://steemit.com/life/@cryptopaparazzi/chapter-one-let-there-be-the-man-and-there-was-a-man-let-there-be-a-woman-and-there-was-sex and FOLLOW ME and I ll do the same :)

Amazing post! I love it. Hey UPVOTE my post: https://steemit.com/life/@cryptopaparazzi/chapter-one-let-there-be-the-man-and-there-was-a-man-let-there-be-a-woman-and-there-was-sex and FOLLOW ME and I ll do the same :)

Amazing post! I love it. Hey UPVOTE my post: https://steemit.com/life/@cryptopaparazzi/chapter-one-let-there-be-the-man-and-there-was-a-man-let-there-be-a-woman-and-there-was-sex and FOLLOW ME and I ll do the same :)

Amazing post! I love it. Hey UPVOTE my post: https://steemit.com/life/@cryptopaparazzi/chapter-one-let-there-be-the-man-and-there-was-a-man-let-there-be-a-woman-and-there-was-sex and FOLLOW ME and I ll do the same :)