Let Em In: The Immigration Controversy

LET 'EM IN: THE IMMIGRATION CONTROVERSY

WINNERS AND LOSERS OF GLOBALISM

Toward the end of the 20th century and the start of the 21st, the UK was governed by a party with a decidedly globalist outlook and metropolitan ideology. There is perhaps no better explanation for why debates over controlling immigration degenerate into accusations of xenophobia. It's a vestige of a time when any such debate was pretty much a forbidden subject. In 2005, when Conservative leader Michael Howard said "it's not racist to impose limits on immigration", he was met with outrage from New Labour. Now, more than ten years later, it is possible to at least suggest that uncontrolled movement of people is not always and everywhere a good thing without being angrily shouted down. But the attitude that you might be xenophobic lingers on. Invariably, suggestions that immigration needs to be controlled is criticised as though it were a call to stop it altogether and become isolationist. Whoever suggests there is any problem with mass migration can be expect to be lectured on the many genuine benefits the free movement of people has delivered.

But one can acknowledge the benefits immigrants bring while recognising that mass migration has not been good for everyone. This was highlighted by a chart created by economist Brank Milanovich and his colleague Cristophe Lakner. Known as the 'elephant curve', it lines up the people of the world in order of income and shows how the percentage of their real income changed from 1988 to 2008. One group- the 77th to 85th percentile- experienced an inflation-adjusted fall in income over the past 30 years. These people are the lower-skilled, working classes of developed countries like the UK. Something like 80 percent of the world has an income lower than that of this group, so given how financially difficult it can be for the working class you can appreciate just how poor most of the world is, and just how intense competition for a better life could become, absent of any control over the movement of people.

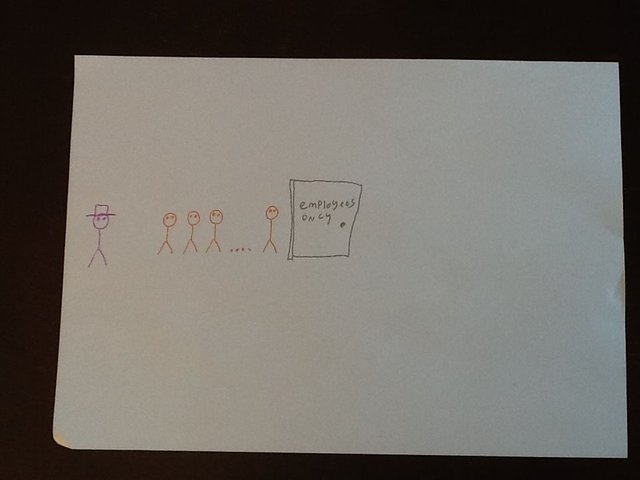

To illustrate why the working classes in developed nations are made worse off by uncontrolled immigration, let's turn to a simplified example. Here we have workers in a factory. The production line does not have sufficient numbers of employees to run properly. Such a situation is not good either for the business itself or the employees. If it were to continue, the plant would close and the employees would lose their jobs.

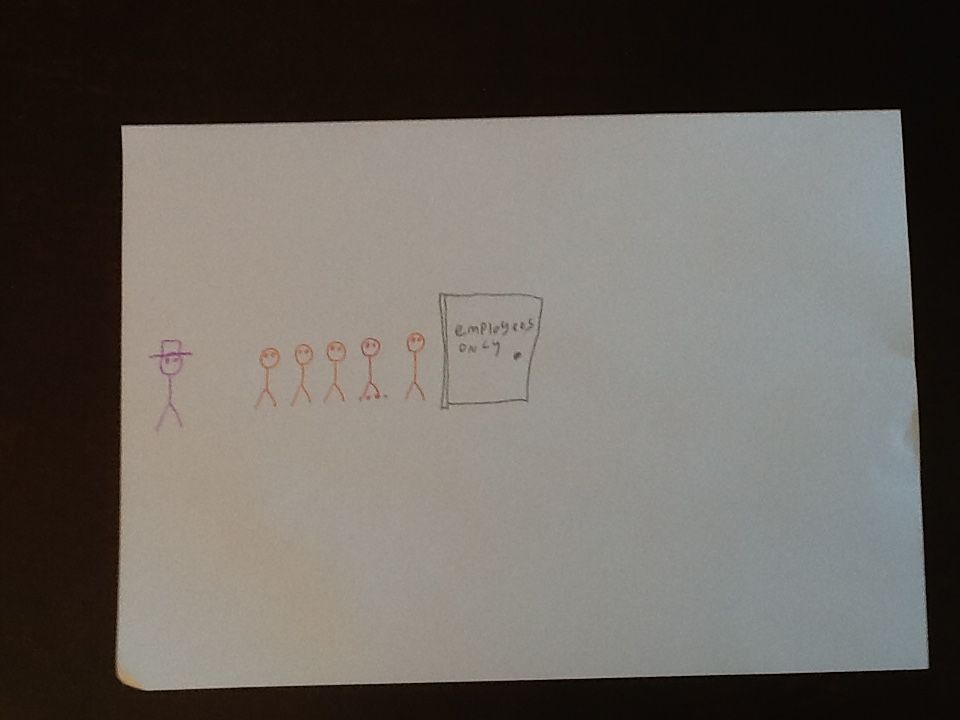

Now, let's suppose the plant has to recruit from overseas in order to fill the labour shortage. From the perspective of the employees, what would be the ideal immigration system? It would be a highly controlled system that only let in as many qualified people as are required to make up the shortage.

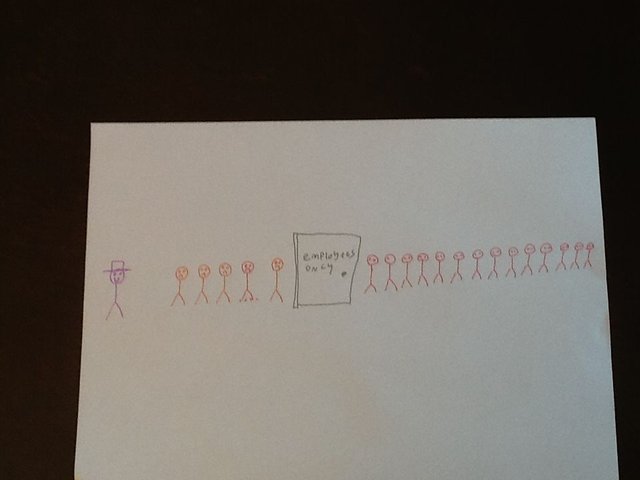

The owners of the plant might see things rather differently, however. For them, the ideal is to have no control over the movement of people and to tempt as many people into the country as possible. Now, given that these people have no vacancies to fill, what use are they, economically speaking? The answer is that they put pressure on the existing workers, who feel they can't raise issues about current standards or even falling standards, for fear of being replaced. "There are plenty who would agree to these conditions", we can imagine any dissenters being told. This pressure to drive down both wages and investment to improve or maintain working conditions is good for the owners, since they get to appropriate more of the wealth that their workforce produces. Surprise, surprise, the top 1 percent on the elephant curve have a line that's almost vertical.

In case this sounds like a mere hypothetical, let's look to some real examples. In 2006, Southhampton's Labour MP, John Denham, noted that the daily rate of a builder in the city had fallen by 50 percent in 18 months. Or consider the findings of Guardian Journalist John Harris, who produced a series called 'Anywhere but Westminster', which included a Peterborough agency advertised rates and working conditions that only migrants would take.

But perhaps the most striking example would be the MD of a recruitment firm who admitted to the authors of 'How To Lose a Referendum' that if it were not for uncontrolled immigration, pay and working conditions might have to improve. All these examples point to the same thing, which is an increase in the supply of labour irrespective of an increase in demand resulting in a reduction of bargaining power, which the monied take advantage of to appropriate even more wealth from those who actually do the work.

It should be noted that such outcomes are not usually entirely due to mass immigration. In April 2007, the Economist published a study of those areas of the UK that had seen the sharpest increase of new migrants over the ten year period from 2005 to 2015. In those areas- dubbed 'migrant land' by the magazine- real wages fell by a tenth, which was faster than the national average, and there was also a decline in health and educational services. But there were other factors impacting these areas too. They suffered cuts to public services following the Coalition's move to austerity in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and they were disproportionately affected by the decline of the manufacturing sector.

Some have argued that these other factors are the real issue and that pointing the finger of blame at migrants is just scapegoating. Consider the words of Justin Schlosberg, media lecturer at Birbeck University:

"The working-class people have had an acute sense that their interests were not being represented by the banks and Westminster. What the right-wing press seeks to do is –rather than identify the true source of the concerns, which is inequality, concentrated wealth and power and the rise of huge multinational corporations that dominate the state. All of that is an abstract, complex story to tell. The story they told which more suits their interests is: the problem is immigrants. The problem is the person who lives down your street who works in your factory, who looks different and has different customs. It plays on those instinctive fears".

Now, in some ways you could say he makes a fair point. Immigrants are not bad people, they are just ordinary folk doing what they can to improve their circumstances. But the fact is that mass immigration is part of the 'abstract, complex story' that is globalism.

So what is globalism, anyway? Is it the brotherhood of humanity, people of all races, creeds and religions holding hands and united under common bonds? If that is indeed what it is, then it would surely be welcomed by the vast majority of us. After all the latest estimates are that only 7 percent of the UK are racist.

But there is another way to look at globalism, and that is to see it as the commodification of the world, its resources and its people. It's a global network of banking and financial systems that seems always ready to blow up and spread systemic risk, the fallout landing on the working classes while the one percenters get government bailouts. It's a global transport and communication system that enables corporations to move manufacturing and other sectors to wherever rules and regulations are more relaxed and people more exploitable. Most damningly of all, it is the commodification of people, sometimes to the point where they are reduced to the status of disposable commodities. The tragic reality of that was vividly illustrated by the sight of greedy traffickers dangerously overfilling barely seaworthy boats with people desperate to escape dire situations, lured by false promises of some other place where opportunities are boundless and nobody slips through the social safety net.

What really awaits these people is sometimes not just low-paid work but actual slavery. Incredibly, when their status as slaves is pointed out, such people often deny that's what they are, because the conditions they came from were so bad their current situation feels like a step up. While one has to feel for people as downtrodden as that, one must also acknowledge what a negative effect it has on the working classes of developed nations. From the point of view of this group, the whole point of a job is to earn a living. To achieve that aim you need to earn sufficiently high wages to alleviate financial anxiety, you need to have a sense of stability and security in your working life, and you need sufficient free time with which to develop a more well-rounded existence. But all that is hard to achieve when you are competing for jobs with people who consider slavery to be an improvement and when jobs are disappearing to places where pressure from unions and environmental groups is either weak or nonexistent and therefore unable to place regulations on exploitation of people or the natural world.

At the same time the globalist commodification of everything suits the wealthy elite. Selling arms to warring nations, offering huge loans to corrupt leaders and supporting coups to overthrow more egalitarian governments and throwing regions into chaos so precious resources can be extracted on the cheap amidst the anarchy are all money-making opportunities. And the consequences offer money-making opportunities too, as people flee from countries ravaged by war and economic weapons of mass destruction with so little bargaining power their numbers put serious downward pressure on wages and working conditions (more profit for the owners) and also increases competition for housing (which forces up land prices, thereby increasing the paper profits of the owner classes).

One has to wonder how things would have turned out if globalism had continued amidst a complete intolerance for debating the issue of uncontrolled immigration. For decades, the working classes of the UK were underrepresented by the political establishment. New Labour's mindset was a mixture of metropolitanism and free-market ideology that imposed a Darwinian struggle for survival on the lives of people, followed by a Coalition that responded to the near-collapse of the world financial system after deregulation led to insane risk-taking with austerity, essentially making the working classes pay for excessive risk-taking and greed at the top. Meanwhile, with even the mildest objections to uncontrolled immigration shouted down as xenophobia, only the extremists were prepared to speak up. People like Nick Griffin of the BNP, or Marine LePen of Front Nationale. More recently, Chancellor Merkle's decision to open Germany's borders to a million mainly Middle-Eastern migrants is seen by some as a reason why the far right Alternative Fur Deutschland won 50 percent of the vote in more depressed areas. That, as in other cases, was the result of simmering dissatisfaction over what globalism had wrought and what intolerant liberalism had deemed inadmissible for reasoned debate.

To quote the words of the Leave's campaign poster, the rise of extremist groups is a sign that people's tolerance for what globalism has done is at breaking point.

REFERENCES

"How to Lose a Referendum" by Jason Farrell and Paul Goldsmith

Wikipedia

good post my friend, good luck always

Great works, I wish you success