Emotional Beats in Storytelling (Part 2: Humorous Beats)

Everyone making games should have a basic idea of what makes a story work. At the very least, even a relatively abstract game benefits from an understanding of how the writer does things. And one of the thorniest subjects out there is humor.

Yesterday I wrote about emotional beats, and one of the things that I want to stress is that emotional beats are fast-paced. You can repeat the same sort of beat more than once in a row, but there needs to be something new to grab on to. Each has its own role as well, so being too fond of a particular type of beat is likely to create an unbalanced story.

The humorous beat is one that you don’t have to use; there are stories with precisely no humor that still wind up being just fine. However, humor has a great power to amuse audiences and transition between other beats, and it also satisfies us in ways that are difficult to replicate. People can tell and retell jokes, and they often require little context. Someone who wants to explain how cool an action beat in a story is or how deeply moving an intimate beat is will always fail to replicate the original scene because those rely a lot more on context.

But even the most benign humor can hurt a story if it’s inserted in the wrong place. There are three general thrusts to how the audience reacts to a storyline: the investment in the world, the investment in the plot, and the current emotional beat.

The Humorous Emotional Beat

The defining trait of the humorous emotional beat (I’ll also call it the comic emotional beat) is that it is funny.

It doesn’t have to be just a joke, but often jokes are humorous. References, music, visual elements, even events can all be part of a humorous beat.

We call stories that are dominated by humorous beats comedies, but they aren’t strictly reserved for comedy, and most comedies don’t have exclusively comic beats.

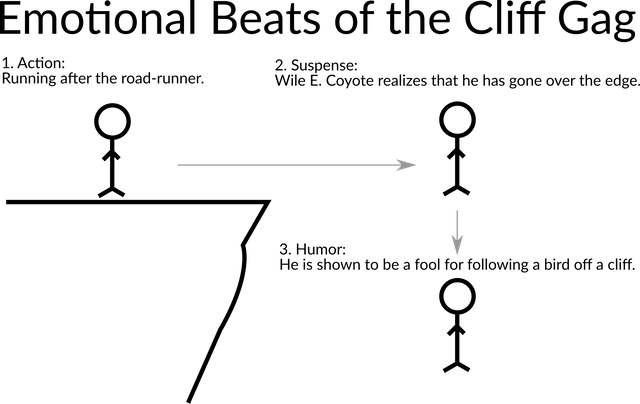

One of the best examples of this is a running gag involving the classic cartoon character Wile E. Coyote.

My stick-figure diagram is not particularly good, but it should illustrate the concept: The gag starts with a Wile E. Coyote chasing the road-runner (an action beat) takes a step out over the edge of a cliff, keeps running for a while (a suspense beat, not a humorous one–yet), and then realizes that he is hovering in thin air before he suddenly plummets, often after gulping or waving to the audience (a humorous beat).

Humor is setup, execution, and payoff. If you’ve ever seen a bad comedy, it probably fails because it’s “trying too hard” and it hasn’t actually earned the audience’s investment. It doesn’t do anything except humorous beats, and it rushes them so that the three parts aren’t obvious. You don't need setup, execution, and payoff to all be comic for the joke to succeed, just the important bits.

Perhaps the best part of humor is that while other beats often feed off of characters’ strengths, you can use humor to highlight their weaknesses without making them look bad.

In Disney’s Moana, the demigod Maui is often highlighted as a lazy and self-obsessed character who doesn’t really deserve his power or reputation (in contrast to the driven and clever misfit Moana). It’s funny, but we don’t get the idea that Maui is ever an antagonist, even if he has to be goaded into doing his job and doesn’t believe in Moana’s vision.

Good Clean Fun

Irony often goes into humor when a subversion of what people expect turns out to be absurd. When Monty Python has people walking around pretending to ride horses, replete with an in-narrative character following them around and making hoof-step noises by banging things together. That’s funny because it’s people pretending to be serious and follow the genre tropes, but not really living up to what you expect. Bonus points if the audience gets the sound before they get the visual, leading them to have the expectation of a rider mounted on a horse, but instead get buffoonery.

Situational comedy is also great. The American TV sit-com gets panned for appealing to the lowest common denominator, but one of the reasons why it works so well is that situational humor is the most optimized form of irony.

Let’s say that you have a married couple (I think of Debra and Ray Barone from Everybody Loves Raymond, but this works with pretty much any sit-com, from I Love Lucy to Last Man Standing. You can have Debra talking about how faithful and clever her husband Ray is; an intimate beat. Then the camera pans or the scene shifts, and in the next room Ray’s hiding in the cupboard because he wasn’t expecting his wife to get home yet or invite friends over and he was twelve spoonfuls deep into a half-gallon of ice-cream that he was eating straight from the container.

There’s an idea that it’s cheap to use humor to yank the audience around, and that’s true to a degree. However, the whole point of humor is that it takes what the audience expects and shows them something else.

Clever plays on words are a relatively innocuous form of humor; if someone says “I’m hungry” and another person thinks their name is Hungry now, that’s one form of word-play. Puns and many types of word-play aren’t really funny (in the sense that they are measured in groans and not laughs, as Isaac Asimov once observed), but they do a pretty good job at serving the same roles as irony-derived comedy, namely moving the story forward while not increasing the tension (more on this in a bit).

Referential Humor

One of the types of humor that can work in moderation is reference-based humor.

In reference based humor, the setup is handled by the audience’s existing knowledge, and the execution and payoff come from your twist on the setup.

For instance:

Your story is set in Ancient Greece and someone mentions hiding inside a wooden statue made as a peace offering, and a character quips “Like that would ever work.”

This is, of course, a reference to the Iliad, where the Greeks made a giant wooden horse as a fake peace offering, and hid inside it to infiltrate the city of Troy.

The problem with referential humor is that it only shows off your cleverness if you actually put cleverness into it. Parodies work tremendously well to leverage this, but if you have a lot of your own dramatic and humorous work but constantly lapse into references you’re going to look lazy.

Look at a Mel Brooks film; they’re almost all parodies of a genre or film. Spaceballs riffs on the Star Wars saga and Blazing Saddles parodies the Western genre, but they all draw more from tropes than from the audience’s understanding of any particular work. Yes, Spaceballs works better if you understand that Dark Helmet is a parody of Darth Vader, but it also references pop culture and sci-fi tropes in general and subverts everything the audience would expect from such a film.

Something like Duke Nukem Forever or Borderlands 2, on the other hand, just takes references from things and tries to point out how stupid/silly they are. Unfortunately, at best they come across as arrogant, taking cheap shots without really rising to show their own strengths, and at worst they retread tired ground.

The internet makes it a little harder to do good referential humor. We’re all familiar with the common memes, so if you’re going to make a reference to deceptive cakes or arrows to the knee, you’ll need to make sure the payoff sticks.

Good referential humor lets the audience feel like they set up your joke, bad referential humor makes them think the joke is on them.

The Taboo

Humor can also be subversive.

Another form of subversive humor is the taboo. This ranges from unexpected uses of naughty words to my own personal favorite, so-called black humor. Black humor is when you joke about something that wouldn’t normally be acceptable. There’s a comedy sketch by Mitchell and Webb about two SS officers realizing that they’re fighting for the bad guys in which they joke about the sorry state of Russian agriculture (anyone familiar with the time knows that Stalin starved millions of people) and the fact that they put skulls on their uniform.

Taboo humor is difficult. If you swear like a sailor, you’re going to put off some audiences. It also loses its whole point; someone who swears all the time just swears all the time. An otherwise straightlaced character who lets a word they can’t say on TV slip at an inopportune moment in front of their boss and family is potentially funny (there’s a scene like this in the classic movie A Christmas Story, where Ralphie lets something profane slip and winds up with a bar of soap in his mouth). If you’re Guy Ritchie and you have an endless pool of excessively profane statements, they might work. One option here is to make jokes that don’t rely on any naughty words, but instead are a “double entendre”; the words themselves are fine, but the implication is dark. Especially in more vulgar works, they can be helpful as a way to return to form.

Black humor has its limits as well. If your characters see someone meet an awful end and someone jokes that “At least he doesn’t have to eat his wife’s cooking anymore!” you are going to kill the mood. A lot of black humor centers around horrible situations, and it’s able to add levity or lampshade things. Deadpool sells itself entirely on the image of its fourth-wall breaking protagonist, most of whose jokes are R-rated and touch on such airy topics as child abuse, amputation, Ryan Reynold’s acting career, and abducting people and turning them into super-soldier slaves.

It’s also possible to have humor in the face of danger that is not dark, but is made dark by its context. I recall a story from World War 2; a squad’s radio guy stuttered under the stress of combat, but not if he sang, so he’d be trying to stammer out reports and then wind up singing them to sing-song tunes. Funny, but dark due to the thematic associations of combat trauma and the subject matter; whizzing bullets and units that weren’t reporting back.

The Role of Humor

Humor is useful because it can wake up audiences after a slow section of a film, and because they can serve as an intermediary. If you have to have an intimate moment with two characters revealing their mutual love, it can be hard to get into and out of that, especially depending on your audience. A hard-boiled action film may manage to work out a confession like this, and a more literary film may be able to simply do slow scene transitions. I think of American Sniper, where the jarring mis-match of action and family drama blend action beats and intimate beats, like when Chris Kyle calls his wife to tell her that he’s coming home after finally besting the sniper that killed his squad-mates.

As a general rule, each beat has a certain level of tension it works best at (intimate beats work at low tension, suspense beats increase tension from low to high, and action beats work at high tension). Comic beats forward the story without increasing tension, and they work at any level of tension. This makes them invaluable because when you’re telling a story and want to be able to make forward progress through a story arc without adjusting the tension, you can do that.

Humor also lets you dial back on otherwise deep and serious tones. We see this a lot in kid’s movies, where going for pure drama could be frightening. Action movies often do this too; they like high tension, but going for pure high tension by string action beat after action beat pushes the plot forward too quickly. Moments of levity enable a transfer to a suspense beat or the like.

Disney’s The Lion King (I refer here to the old-school original, since I have not yet seen the “live-action” remake) uses humor to great effect when Simba and Nala are reunited after Simba has left his pride. Simba leaves his pride in a moment of shame (alleviated by the comic figures of Timon and Pumba, who sing about peace and love), and when he goes on to leave his new-found family and return to his destiny they (although not intentionally joking) make a comic pair because they talk about him leaving like a child’s departure, though Simba is by this point a fully-maned adult lion. This is funny, and helps to mitigate some of the more sorrowful associations and let the animators tell the story they want to tell without leaving the matter unaddressed.

Comic beats have one major potential problem: it’s very easy to disconnect them from the overarching plot and world arcs. I could go into this, but there’s already a good analysis of this done by The Closer Look, a YouTube channel dedicated to film criticism.

However, when used right, comic beats can really elevate a storyline.

Application in Games

In games, humor is often difficult. Interactivity can change the setup of humor, which makes it fall flat.

For this reason, referential humor is tempting, since then the player contributes their own knowledge, but it’s hard to name games with good referential humor in them because too much reliance on it confuses players or feels artless. Something sly works; for instance, The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim featured a bug where getting hit by a giant would send corpses flying into the air. Although this was originally treated as a bug, it became something that was an in-joke. Giants just do that to people.

Little easter-eggs scattered throughout the world can work well. Fallout had its Wild Wasteland trait, which optionally let players bump into the creators’ takes on pop culture. Fallout: New Vegas, for instance, included references to a much-maligned Indiana Jones scene, Lassie, Monty Python, Star Wars, and Robo Cop. One of the strengths of this is that it’s opt-in, so you’re not forcing it on anyone, but found easter-egg content can work in most cases so long as it doesn’t intrude.

The most common form of (deliberate and planned) humor in games is probably in dialogue, and I think this is where you get the most mileage unless you’re really clever. The limit here is that you’ve got the same opportunities you’d have in speech, but not a whole lot more.

A game that makes great use of this is Shakedown: Hawaii, a game with the same sense of parody that you might expect from Mel Brooks. The protagonist is the owner of a multinational corporation that winds up watching business news for “tips” (it’s an investigative reporting channel, detailing how companies have been fleecing customers), and acting exactly like a stereotypical moustache-twirling villain. There’s a lot of cheap shots at characters due to their character flaws (or bad knees), but it comes together to be subversively funny.

The usual problems persist; you don’t necessarily get the same pay-off as you might. I was recently playing Wolfenstein: Young-Blood, and a lot of the more deliberate attempts at humor fell flat or were forced. However, there were some interesting bits; the way the enemies talked about the player characters as terrors that go bump in the night has some comedy potential when it’s not being played straight. However, of fifteen attempts two or three land.

Wrapping Up

Comic beats go a great way toward letting you move forward with action and keep audiences engaged, and while they’re not necessarily great communicators of story (though they can be), they can contribute masterfully to tone.

Just be aware that they’re also able to destroy a story, especially because they can actively cause harm when they fall flat, where most other beats just waste time.

We'll talk about action beats tomorrow before continuing to intimate and suspense beats.

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.