Zorker's Must-Read Comics: Animal Man #5 (1988, DC Comics)

When was the first time a comic left you feeling, actually feeling, something after you closed the cover and set it aside? I don't mean a feeling of satisfaction in that you enjoyed the story, or a feeling of disappointment that it didn't turn out very good, or a feeling of rage because Marvel cast Thor as a woman for a bit and NOW READER SMASH!! I'm talking genuine emotion, like you were personally invested in the story, in the characters, in the outcome, and when it ended, you felt like a part of you will always exist within the pages because it was such a deeply personal and moving experience.

Back in the 1980's, the idea of comics being anything more than cheap, disposable reads for children was absurd. While writers like Alan Moore and Frank Miller were pushing boundaries and producing stories that were aimed at older audiences, the bulk of mainstream comics, especially those put out by Marvel and DC, and especially their A-listers like Spider-Man and Superman, were produced with a goal of selling those books to readers of all ages. That's not to say they never tackled serious issues, or used the medium to ask thought-provoking questions, but the prevailing wisdom of the day was that kids bought comics. If those comic characters could be used to sell toys, or cartoons, or even feature films that was even better, but as long as the end of the story saw the superhero punching out the supervillain, that was what mattered.

That's one of the reasons I have such respect for the old Marvel Transformers comic from the 1980's. What should have been an easy cash-in on a hot toy and cartoon property with a four-issue limited series run in 1985 instead astonished Marvel with the amount of interest it generated in readers. Initially pegged to end on a high note, with Optimus Prime and the Autobots winning the day against Megatron and his Decepticons, issue 4's script was tweaked and the final page re-drawn before it went to print. Now, instead of a simple speech from Optimus about having won the battle, Shockwave showed up out of nowhere and blasted the Autobots into scrap.

The bad guys won, and the question, "How do the Autobots come back from that?" left readers pining for more. Pining for so much more, in fact, that the series spawned seventy-six additional issues, and numerous other mini-series and spin-offs over the course of its seven-year run. The Transformers #4 from March of 1985, was my first emotional comics moment. It would not be my last.

Grant Morrison was part of DC's "British Invasion" of the mid-80's where they tapped talent like Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore from the UK to write American books. Morrison established one of his trademarks with his first series, raiding the backlog of characters owned by the company and using them to tell compelling stories by either updating them to modern standards or simply re-introducing them after a long period of disuse.

The first character to get the Morrison treatment was Animal Man, a character originally created in the 1960's during a time when Marvel and DC were both competing with one another to create and trademark names and looks for heroes and villains. The goal for both studios wasn't so much to invent people with interesting powers or personas with which to tell stories as it was to prevent the other guys from getting there first. There was a Cold War of sorts at play here for a few decades, which deserves its own blog post in the future.

Initially conceived as "A-Man" by Dave Wood and Carmine Infantino, professional stuntman Buddy Baker made his debut in the pages of Strange Adventures, a sci-fi and fantasy anthology series. Later dubbed "Animal Man" for his ability to absorb the abilities of nearby animals and use them like his own super powers -- giving him the ability to fly due to a nearby bird, or enhanced reflexes if he can get near a cat -- he had a short run of stories in Strange Adventures until his potential petered out and he was shelved in favor of other, newer, more interesting heroes. Through the next twenty years, Buddy showed up only intermittently as a background character, sometimes appearing as part of the "Forgotten Heroes", a super-team made up of minor DC back-catalog characters like Dolphin, Congorilla, and Immortal Man. Following the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover event of 1985, Animal Man wound up in limbo as one of the many characters not explicitly killed off, but not shown to have explicitly survived either.

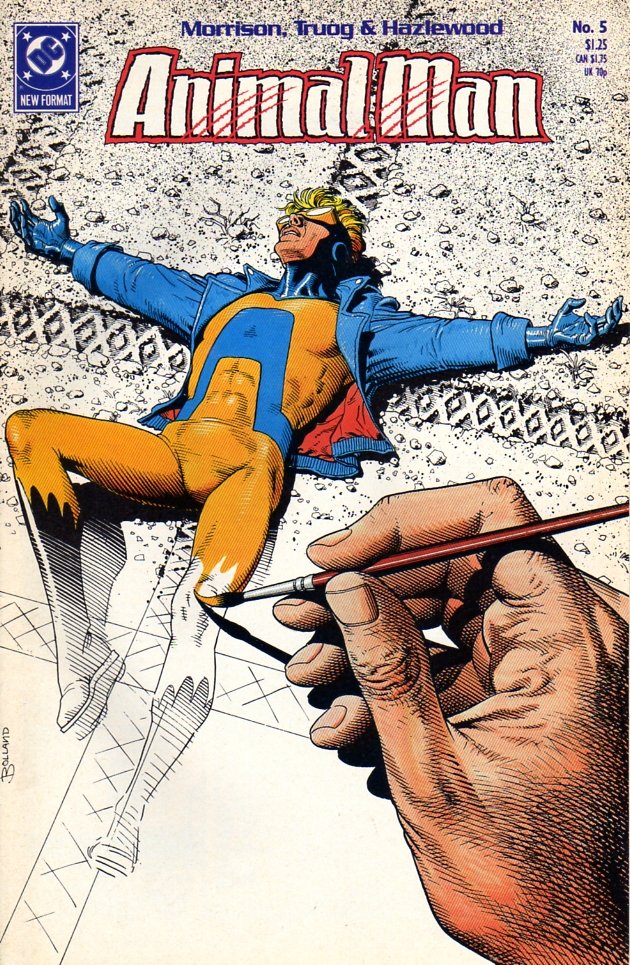

All that changed when Grant Morrison dragged Buddy Baker out of the filing cabinets in 1988 for what was intended to be a four-issue mini-series. Reader response to this revival of Animal Man, which cast him as an out-of-work Joe Everyman in his thirties looking to recapture his glory days as a super hero, was unexpectedly positive, and the book's sales took off. DC thus tasked Morrison with expanding Buddy's universe into an ongoing monthly series. After concluding the four-issue story arc, which saw Buddy facing off against B'Wana Beast (another refugee of DC's enormous and underutilized filing cabinet of "bad guys we invented decades ago and forgot about") before ultimately teaming up with him to stop a mad scientist engaged in animal experimentation, Morrison took one issue to tell the sort of self-contained story it's almost impossible to do correctly: the issue where the title character is only barely involved. The result was Animal Man #5, "The Coyote Gospel", and even now, some thirty years later, it stands as one of the best single issue, stand-alone comics ever written.

Please note: I'm going to spoil the hell out of this story in this post, so if you haven't read it, I cannot stress this enough: bookmark this essay, grab a copy off Ebay, pilfer @blewitt's backstock, or hit up @cryplectibles, and come back after you've read it.

All images you see in here are scanned by me from my own sources.

"The Coyote Gospel" is a story in which, as previously noted, Animal Man plays almost no role. He's in the story, but it's not his story, and he's powerless to affect the outcome. In fact, not only is it impossible for him to affect the outcome, by the close of the final page, nobody in the story has the complete picture of what the hell just happened. Only the reader is equipped to put all the pieces together and fully understand the tragedy which just played out in the panels before us. The final page of the comic reminds us of this by not just breaking the Fourth Wall, but shattering it into a million pieces and pissing on the rubble. It's a story you could only tell in a comic book--no other medium is sufficient.

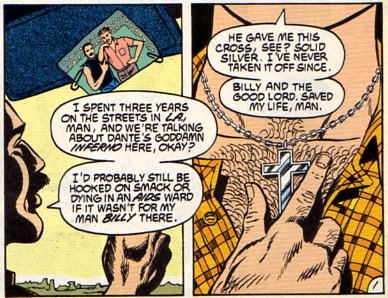

"The Coyote Gospel" begins with a truck driver picking up a teenager named Carrie, hitchhiking through Death Valley on her way to "be somebody" in Hollywood. He attempts to discourage her from this path by relating some of his own history living on the California streets:

The miles roll by as the pair sing along to the radio, when suddenly a shape looms ahead of them on the road. Unable to stop in time, the eighteen-wheeler barrels over it, leaving behind the body of a wolf that walked on two legs. Carrie, who couldn't see what it was due to the glare of the sun on the windshield, asks what they just hit.

"Forget it," replies the truck driver, an expression of pure terror on his face. "Don't look back. Keep your eyes on the road and don't look back." He takes his own advice as the roadkill carcass bakes in the desert sun.

Suddenly an amazing transformation takes place. The body of the animal, shorn nearly in half at the spine by the treads of the big rig, begins to twitch. The two halves slither closer, stitching together as if by magic. The shattered pelvis repairs itself. Broken ribs resume their normal positions in a chest cavity now holding lungs which painfully re-inflate. Within minutes, the healing is complete, and the two-legged anthropomorphic dog creature, a coyote, stands and walks again. "Behold!" Morrison's boxed text tells us, "The miracle of the resurrection!" The coyote continues its journey through the endless desert, and we're informed this happened a year ago.

We switch to Animal Man's home, where he's emptying all the meat out of the fridge. His experiences over the previous four issues have left him unable to reconcile the suffering of animals transformed to food for human consumption, so out go the groceries and in come the plans for him and his family to live a fully vegetarian lifestyle. That he made this decision without consulting his wife or their two children starts a heated argument. Unable to resolve the situation, Buddy storms out of the house, grabs the powers of a passing bird, and flies out into the desert to cool his heels and collect his thoughts.

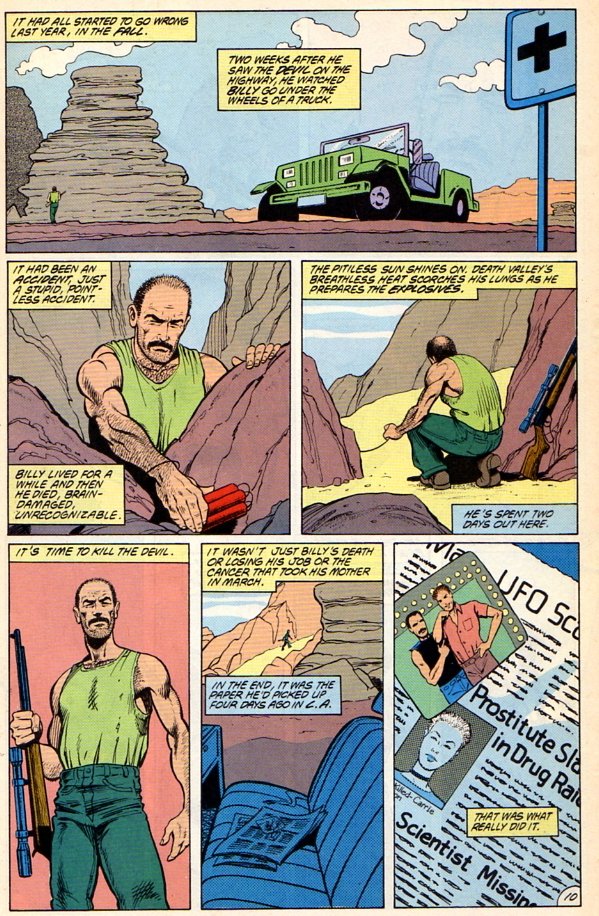

Buddy's not the only person in the desert on this day:

Seems our truck driver has had a rough year. Ever since seeing what he believed to be the Devil on the highway, nothing in life has gone right for him. The man he loved died in a senseless accident. His mother lost her battle with cancer. His job's gone bye-bye. The straw which broke the camel's back, however, was a chance encounter with a newspaper relaying Carrie's own fate. He's now returned to the desert with an assortment of explosives, a high-powered rifle, and two bullets. His aim is to kill the Devil which brought this misery upon him.

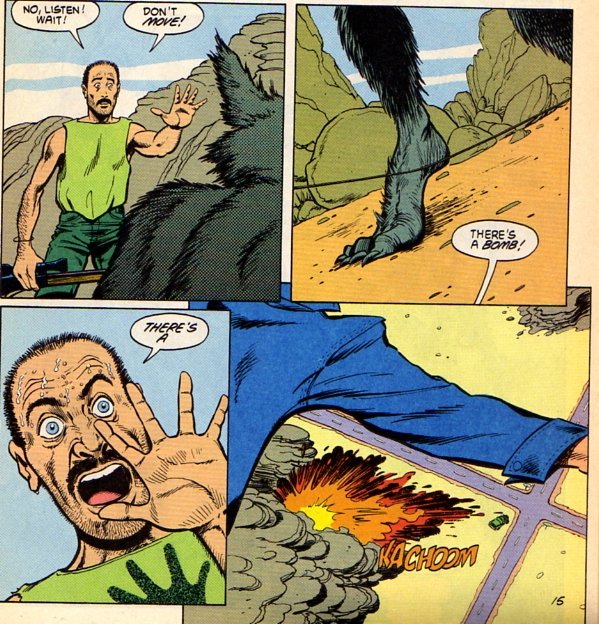

His first shot is successful, blowing the coyote off his feet, sending him toppling down into a canyon. Then, to his amazement, he sees the creature begin to regenerate, to re-form after what should have been a fatal fall. Knowing he needs to get close enough to deliver the final blow, but also needing to delay the animal's escape, he sends a boulder down into the canyon to crush the coyote. Scrambling down the incline, he arrives only to see the creature stand up again, completely re-made with no injuries. It begins to walk toward him, and suddenly the man realizes he's made a terrible mistake:

The explosion attracts Animal Man's attention, and he descends to check things out. As he examines the jeep parked nearby, the regenerating coyote ambles up to him, removes a parchment tied around his neck, and hands it to Animal Man, who opens it in confusion, and the reader learns it is "The Gospel According to Crafty".

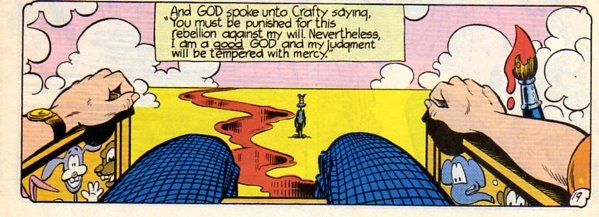

Crafty comes from a world of violence, where anthropomorphic cartoon animals set upon one another in a never-ending cycle of cruelty and brutality. In this world, there is no death. Even the most grievous injury heals within moments. The feuds, the battles, and the acts of sheer cruelty resume in short order. Finally, tired of the ceaseless carnage, Crafty stormed into the great sky elevator leading to heaven, and confronted the God responsible for this cruelty:

"Chuck Jones...is that you...?

The God makes a pact with Crafty: He will put an end to the unending violence of Crafty's world if Crafty agrees to walk forever in a perpetual hell, bearing the suffering of the world upon his shoulders alone. Crafty agrees, and the God banishes Crafty to Earth, dropping him in the middle of the desert, just in time to encounter a familiar 18-wheeler and its occupants.

Here, for the past year, Crafty has walked, suffering the unimaginable pain and horrors of death in the hopes that one day he would return to confront his God, end his reign of tyranny, and create a better world for all of his cartoon brethren to inhabit. All this is recorded upon his scroll. Animal Man's response, however, is...not exactly what we might expect:

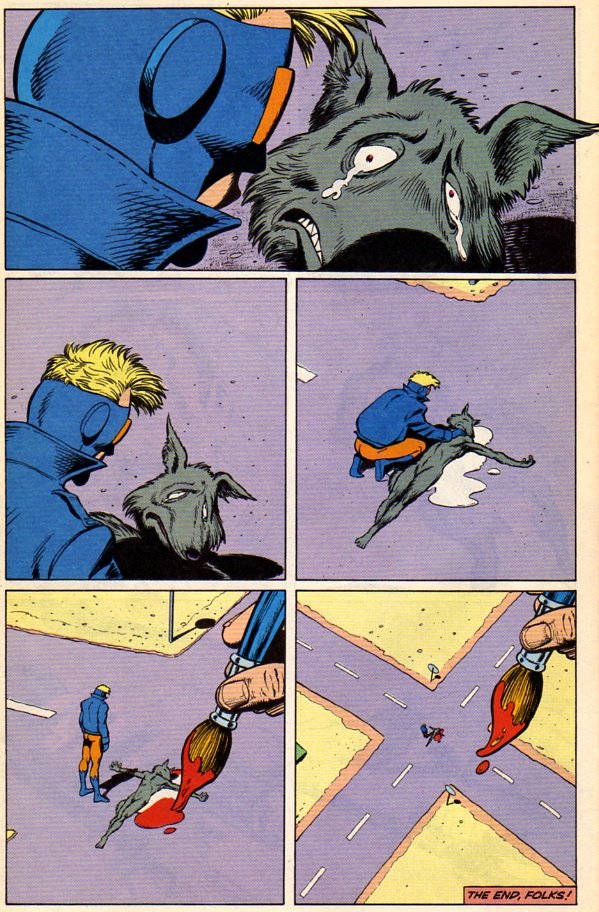

With the last of his strength, the truck driver crawls to his feet, steadies his aim, and sends his second bullet, the special one, the magic one forged from the silver of the cross inscribed with, "All my love," which Billy gave him those years ago, speeding on its way. His aim is true, a solid shot through the left chest cavity, and into the heart.

Crafty for once feels no physical pain as he dies, but the anguish at his failure to conclude his mission is writ large within his eyes. Both he and the truck driver expire as Animal Man stands, unable to help or even comprehend what just transpired, and Morrison ends the story with a scathing indictment which speaks louder than any word balloons ever could:

This is why people love Grant Morrison. Within the span of twenty-four pages, using the world of a third-tier DC hero but not involving him in the plot, he completely deconstructs the Looney Tunes and Merry Melodies of our youth and shows us to them in a way that is no longer funny, but horrifying and thought-provoking at the same time. Crafty, in this book, dies spread-armed in the middle of a desert crossroads, not because Grant Morrison dictates it, but because we, as the audience, so dictate with our love of fantasy violence borne across thousands of hours' of animated cartoons and millions of pages' worth of funny books printed over the years.

Crafty, in a sense, is our own innocence, rendered up to innumerable, bloodthirsty 'deities' of our own crafting.

What's equal parts impressive and amusing about this story is the sheer number of hat tips Morrison gives to Warner Bros. over the course of the issue. Crafty, for instance, is a synonym for Wily, as in 'Wile E. Coyote'. The panels featuring Crafty's pain and misery often parallel scenes depicting Wile E.'s doom and defeat at the hands of the nameless Roadrunner: witness his fall from the cliff after being shot by the truck driver: a series of four panels showing the same scene with the only change being the coyote's figure getting smaller and smaller until it smacks the ground in a cloud of dust. Witness the same as it looks up at the shadow of the boulder which grows larger, crushing it beneath its weight. The truck driver, just like the roadrunner itself, has no name--neither the reader, nor Crafty, knows the name, the identity, of the individual who brings about his destruction.

But it goes even deeper than that. After picking up Carrie, she and the truck driver sing along to a song on the radio. The song, which is playing as they run over Crafty, is "Roadrunner" by The Modern Lovers. The truck he drives is owned by AJAX, another four-letter company starting with 'A' which is seen to plague Crafty in the flashback sequences where his AJAX-brand cannon goes terribly wrong. There's even a full-page ad for Looney Tunes merchandise in the middle of the comic (though this wasn't deliberate--WB ads appeared in a number of Animal Man books in addition to this one). Morrison closes the story with the phrase, "THE END, FOLKS!"

The Coyote Gospel smacked me dead in the face the first time I read it, and left me teary-eyed at the senselessness of the outcome. What's especially effective about Morrison's technique here is that the final panel of issue #4 is just like the top panel from the last page of issue #5: an animal staring out at the reader in terror at its pending fate. One issue earlier, we were cheering at this outcome as it appealed to our sense of justice. One issue later, we're crying at the injustice of it all. This is how you do contrast, folks.

The Coyote Gospel was nominated for an Eisner award in the "Best Single Issue" category. Morrison himself was nominated for "Best Writer", and Animal Man received a nod for "Best New Series". That it didn't win any of these is sad, but since this was the same year Alan Moore produced The Killing Joke and Kitchen Sink Press published Jim Vance and Dan Burr's Kings in Disguise (both of which beat out Animal Man and Morrison for the awards that year), it's somewhat understandable.

It's a towering achievement when a single issue of a comic book can stand alone, but it's an even larger achievement when that issue can be read by anyone, including non-comic fans and people who don't even know the title character, and still be touched by the story. The Coyote Gospel epitomizes the idea of a "must-read" in the world of comics...but it's not the full story. To get that, you also need Animal Man #8:

Why Animal Man #8? Is it a sequel? A continuation? Does it bring Crafty back somehow, or let Buddy in on the secret of the wandering coyote's scribbles? No, none of the above. You don't need Animal Man #8 for anything related to the four-color artwork or story it tells of Animal Man's first encounter with Scottish arsehole extraordinaire Mirror Master. You need Animal Man #8 for something you can't get just by purchasing the collected trade paperback: the letter column.

Depending on the publishing schedule for a book, anywhere from 2-4 issues after a story hit news stands was when you could see the reader response to such stories in the letter column. And holy shit, did The Coyote Gospel get mail. The entire two pages of "Animal Writes" was devoted to nothing but reader feedback to issue 5. As assistant editor Art Young puts it:

"The Coyote Gospel" prompted so much reader speculation that we've decided to run excerpts from the huge pile of letters we received, in order to hear as many of your interpretations as possible.

Twenty-one separate letters, or portions thereof, are reproduced here, each one attesting to the power and humanity of Morrison's story, along with Chas Truog and Doug Hazlewood's artwork, and Brian Bolland's powerful cover. Some saw it as Morrison's indictment of religion, others (as I do) viewed it as a nuanced look at the reason we find cartoon violence so fascinating and entertaining. Most agreed comics were the only medium in which you could tell a story like it. Grant Morrison's run on Animal Man is legendary, but for as great as the whole thing is, The Coyote Gospel is the, er, "acme" of everything we read comics for.

You’re the best damn comic blogger on Steem! Or maybe anywhere... great article.

I haven’t read Animal Man (it’s on the to do list!) but forged through this since I don’t mind spoilers. I’ll be looking to add this to the collection and study it more in the future.

One of the nuances that strikes me is how Crafty is depicted with Christlike imagery, while having an origin story akin to Lucifer. That’s an interesting dichotomy to me with a lot to unpack. That gorgeous Bolland cover also hints at how the Crafty/creator relationship could be an echo of Morrison’s relationship with his own characters.

Someday... someday I’ll get it all read...

You're being far too kind, but I'll accept the praise anyway. Thanks for your confidence. :)

Morrison actually drops into this territory in later issues of Animal Man, where he literally inserts himself into the comic as Animal Man's author, and the two come face to face. But yeah, there are layers upon layers of "The Coyote Gospel" to unpack, and this could have been twice as long. I just fear boring readers by writing too much. I'd rather leave people wanting more as opposed to wanting me to shut up. :)

Morrison only did the first 26 (I think...maybe it was 28?) issues of Animal Man, then he moved to Doom Patrol starting with issue, like, 19 or something, so there's something else to consider.

I think that's true... @modernzorker really loves what he does 😊 and that's best...

Wow, great article! This is definitely one of the classics, and you've done a great analysis here.

I didn't know the but about Transformers changing the ending at the last minute, turns out it was a good move. I always feel a sense of vindication when the readers aren't given what they want, but it turns out to be what they needed.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.