A baker needs to measure everything

That’s right. Read to learn more about preparing the ingredients for baking.

It isn’t hard to find a recipe on the Internet that would be like: take two cups of flour, a nibble of yeast, a handful of hand-picked seasoned salt; pour oil in a medium-small stream for half of the time to say Our Father, mix and bake. Don’t get me wrong. These are often some awesome recipes, I even use them sometimes, but I cannot function like that. The first time I make it, I weigh all the ingredients and take notes. It all has to be precise.

Well, it doesn’t. I need it this way. Small deviation won’t break anything, it will just be different than what the recipe says.

Every now and then I get a question: Breadcentric, I did everything as the recipe said. It was supposed to give this:

Source: Pixabay

but gave this instead:

Source: Pixabay

What would you advise?

And we start trying to guess everything. Suddenly it turns out potato flour was used as wheat flour was not available, a pipe burst so a third of required water was used, 7 grams of dried yeast were used because one had no way to weigh 2 grams (and the small detail of using fresh yeast was ignored).

This.

Can’t.

work.

Baking bread is a process happening on many layers in parallel:

- handling the dough

- chemical reactions

- biological processes

- thermal processing

Many of them overlap and influence each other. Water binds with glutenin and gliadin to form gluten, and the rest gets soaked up by starch and grains. Amylase decomposes starch into glucose which then gets eaten by yeast and lactic/vinegar bacteria. The salt takes part in the chemical reactions - if you forget about it, the crust will be rough and salted butter will not fix the flavour. While baking, gluten coagulates and forms the structure of the loaf. Before this happens, the microbes have their last, most aggressive metabolism phase. Scores give a direction to loaf’s expansion. Alcohol evaporates. Lastly, the crust is formed and gets brown because sugars turn into caramel. When cooling down, the moisture is escaping, stabilising the crumb and softening the crust which got a bit hard in the last phase of baking.

There is a lot of it. Can you imagine a shift manager in a chemical factory that tells his employees to use five handfuls of an ingredient for a chemical reaction? Or a steel mill where the furnace is heated up based on an engineers gut feeling? Or a doctor that inject a more or less right amount of a medicine into your vain? Similar goes for baking.

Every element matters when making bread. First we’ll talk about

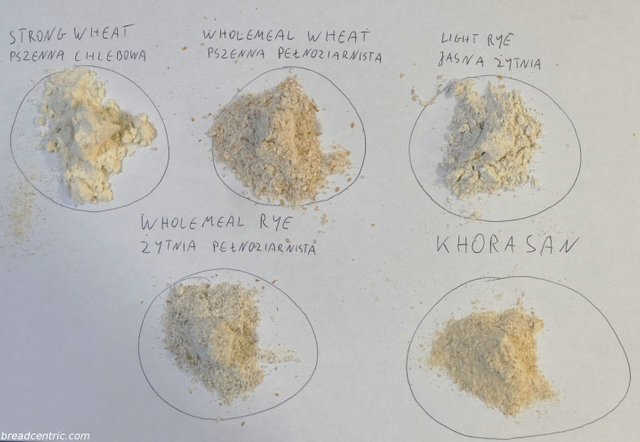

Type of flour

Let’s take 100 kg of flour and inject it into a combustion chamber at a lab. Yes, flour is highly flammable.

I wouldn’t mind seeing someone sift 100 kg of flour onto a flame.

German classification of flour types states how many grams of ashes one gets from burning the mentioned 100 kg of flour. It’s also used in Poland.

Flour is mainly carbs. They burn very well and form water and carbon dioxide. In reality we also get something more - the bran also contains a lot of minerals and they form ashes. This lets us classify the flour with a number from 450 to 2200 (there may be more, but these are the ones I remember).

The more bran flour contains, the more water is needed to get a nice dough. At the same time wet dough doesn’t hold structure that well, so you need to get it right.

To make sourdough it’s better to use a wholemeal flour as bran is what yeast and bacteria usually live on.

Other countries vary. There are some types in Italy based on how fine the flour is, there is something similar in France. In The United Kingdom (and potentially also Ireland) we get plain, strong and wholemeal wheat flour, and usually light and dark (and sometimes wholemeal) rye and spelt. I think it’s a bit similar in the USA, but they also get all purpose flour which is somewhere in between plain and strong in terms of gluten content. Some mills also sell super strong or Canadian which has an insane amount of gluten.

This isn’t however the only characteristic of flour. Depending on the grain variety and location of the land flour can have varying protein content and this means you may need a different amount of flour to get a similar result. Enter

Hydration

Hydration is weight of water in relation to weight flour expressed as percentage.

Many bakers provide this information in their books. Why is it important? I’ve recently had a strong flour which would not let me make proper obwarzanki and our regular white bread had a dough like soup. If I added a teaspoon of gluten per 1.5 kilo flour, the dough properties improved significantly. Then I got Canadian grains strong flour (UK flours are usually a blend of British and Canadian grains). While I usually add 1.2 kg water to 1.5 kg flour, this dough got very dense and springy. It started winding on a dough hook. A huge change. My sourdough didn’t have enough strength to lift the dough before baking and then the bread would burst in the oven. I had to use 1.5 kg water and then the dough would cooperate again.

When the grain doesn’t have enough sun, not much protein is created and the flour is weak, the ones grown in Canada are usually summer varieties (sown in Spring, reaped in Summer). Mixing them can give a desired result but in my first case something did not work.

Usually you won’t find recipes below 60% hydration and above 80% is usually only ciabattas and other shapeless marvels or seedy and wholemeal breads.

Hydration is not the only measure expressed in percents. I present to you

Bakers’ percentage

Two of the books I know provide percentages: „Bread“ by J. Hamelman and „Flour Water Yeast Salt“ by K. Forkish. I would recommend both.

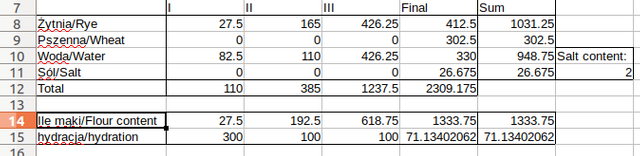

If you calculate the total amount of flour in the recipe, this makes 100%. All other ingredients are calculated as percentage of the total flour weight. You get the hydration, salt (usually 2-2.5%) and so on.

One one hand it may sound strange, but then each bakery decides how much dough to prepare. Therefore percentage is simpler way to calculate amount of ingredients. We also see certain details about the dough:

- salt is usually 2%. You can increase slightly on the hot days (up to 2.5%) to slow down the yeast

- you know the hydration and knowing the expected properties of dough you can adjust the recipe to your flour - it can have much more or much less protein in it. You will roughly know what to prepare for

Interestingly, bakers' percentages can sometimes be used on a

Scale

There's one I'm after:: MyWeigh KD8000(Manufacturer's website). It costs around £40 and can calculate percentages. It looks nice and is a professional product. Sadly, it's also a bit too big, so I got myself a Double scale by Salter from a Heston Blumethal's products line (manufacturer's website; if you want one, do some googling as there are cheaper offers online). I have a scale that can measure up to 10 kg of dough and also measure as little as 0.1 g. It's quite important as usually one doesn't prepare large quantities of bread at home and I often end up requiring 0.5 g of yeast or 5 g seeds. Once I already have two kilograms of dough on the big scale, getting such small measurements in there isn't easy and I can measure them separately. Another advantage is that the scale is reasonably small and can fit in the cupboard.

I remember that in one of my recipes I also suggested that instead of measuring 5 grams of seeds, one could bake 200 loaves and just add 1 kilogram of them. As funny as it may sound, bakers usually do that - when you prepare tens of kilograms of dough it's easier to get precise quantities of ingredients. On a home scale it's much more probable to for instance add 15 and not 10 grams of salt and this makes a huge difference. So yes, bakers often measure ingredients in

Packagings

You get a 16 or 25 kg bag of flour and measure the rest to match it. If you make big orders, you could ask your source to prepare packagings matching your needs.

In my case recipes are often based on the volume of the mixer's bowl - 6.7 litre. I get three loaves in Ikea bread pans from this. If I'm to make two, it's easier to make three - I'll always find someone to give the third one to and I use the "standard" quantities of ingredients. Not having to recalculate and remember is an extra bonus.

If one can use a scale, if I use the size of a bowl as the base input, maybe we could also measure by

Volume?

No.

Seriously.

A cup means something slightly different in different countries, a flat tablespoon will be different than a heaped one. And how heaped is just a tablespoon? Many households in Poland don't even have a standard measuring cup at home.

I know it's slightly different in the recipes in the US, but still not perfect.

How much does a cup of sugar weight? Regular one? Caster sugar? Icing sugar? What about salt? Coarse, fine or flakes? What about flour?

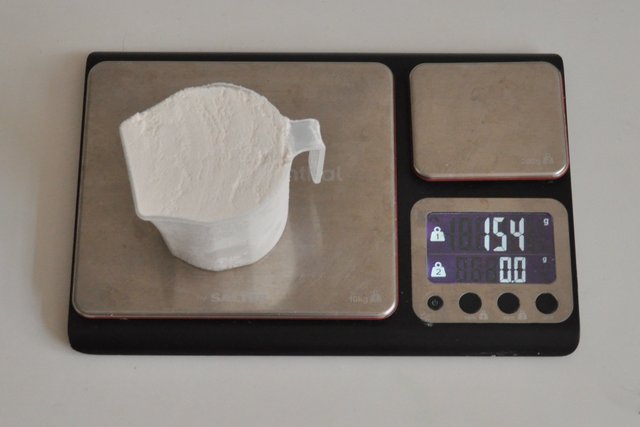

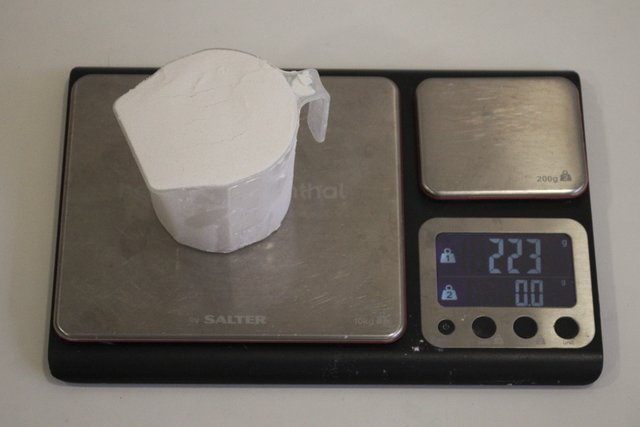

I've made a small experiment: I weighed 250 ml of flour. The results include the weight of the measuring cup which is 25 g.

Sifted strong (bread) flour:

Packed strong (bread) flour:

Empty cup:

130 g vs 200 g of the same type of flour in 250 ml cup. One may say I'm trying to manipulate a bit, but if you think so, try this: Do you have a bag of flour at home? Better one just opened. Take something to measure, for instance a boiled egg cup and take some flour from the top, no packing, no sifting. Weigh it. Then take all the flour out except for a bit at the bottom, take the same amount out and weigh it. Is there a difference? Maybe not 50%, but you should get some 10%. Next time you follow a recipe think: what did the author do? Pack or sift?

If I decide to go for a such recipe, I use given units and then weigh the ingredients and note it. Sometimes I ignore that much detail, but not often.

It all has a purpose - it influences

The properties of dough

Let me invite you to one of many discussions on a bakers discussion board. Some people took an effort to compare flours available in the US and there are quite some differences. As I've mentioned, I used to be happy with the flour I was ordering and than then same bread could give me non-satisfactory results. Then I got Canadian flour and in one of my recipes I head to increase hydration from 73% to 90% just to get dough with similar properties. That's some business - 100 g more of a product just by adding water :P

Less sun is enough to make the flour weaker (less protein). Some rain during the harvest time and the grain can start sprouting and give a weaker flour. Mills can try to standardize their products, but sometimes it's not that easy. In the UK it's usually achieved by mixing British grains with Canadian - the difference in protein content can be huge and if the whole water goes into gluten bindings, the dough will not have enough flexibility to expand and will become very dense.

Such differences can be detected rather easily when you always follow the same recipe. The bakeries (from what I've once read) it is common to make some test dough to specify required modifications. Using technology is also an option. There is a device called farinograph. Just be aware I'm an amateur and don't have any experience with such things. I have found an article in the specialist magazine in Poland. I'm not going to translate it, sorry, but you can go to the bottom to se a graph with comparison of different flours of the same type. Also you can view a video from a mill in Krakow to have a look at what tests can be done in a laboratory. ADD A LINK PLEASE

So yes, it does matter what type of flour you use at home.

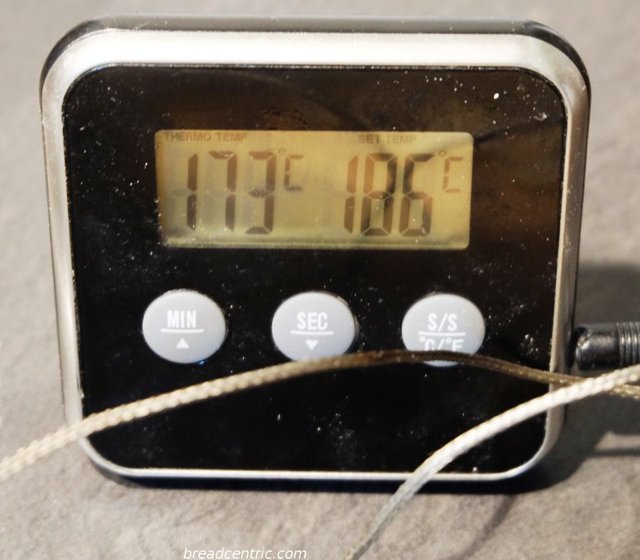

Temperature

Of course everyone know a proper temperature is needed to bake and for bread it should be rather high (but not always) and it's best when the bottom of the oven is heated and when it stably releases the heat to the loaf. Everyone also knows that the heating elements in the oven always heat 100% power, so even if the temperature estimation mechanism is quite efficient, if the heater goes on and off, the bread could be baked more than the temperature would ensure. To compensate for that when baking at home, one can use a baking stone or cast iron pots. Or at least cover the loaf with a dome made with aluminium foil and such.

But it's not only that. What also matters is temperature of the dough. In hot weather your dough will rise faster, in cold one - slower. Warm dough will rise faster than a cold one. J. Hamelman provides expected temperature of the dough after mixing to know what conditions should be expected. Do you remember that when you extend or shorten the proofing time, the enzymes can do something different than expected?

The same Hamelman provides formulas to calculate the temperature of dough. The take friction into account. Yes, your kitchen robot heats your dough up. The friction factor is measured through a test on the machine and then used in baking.

Time

A baker needs to measure time. Making bread is mostly waiting. Of course when you do it for a living, you don't just wait, you prepare something else. K. Forkish described the whole day in his book. He even included time for a coffee, clean-up, warming the flour. There is no time to waste.

What is it like at home? You prepare a levain, wait 12-16 hours, mix dough, leave it to rise for about two hours (this usually involves stretching and folding. Next shaping, two more hours proofing. Or maybe cold proofing overnight in a fridge? I just wait and wait.

Spreadsheet

When I prepare a new recipe, I use some help from a spreadsheet. I prepare proportions, amounts of ingredients, try things out, adjust what hasn't worked out and repeat. It's worth running a diary or at least remember what got changed compare to the original recipe (both in the recipe itself and in the surrounding conditions) and how it influenced the result. This helps you plan the next approach.

There are also apps for storing bread recipes such as BreadStorm. Sadly to use it I would have to buy an Apple products. I'd love to write something on my own and release it as Open Source/Public domain. Maybe one day.

So why doesn't my stone look like a bread?

I can make bread, but not necessarily talk to a magic ball. Some things can be spotted, but some I cannot. For instance when a loaf has a weirdly white crust - I don't know why this happens. I don't know what went wrong in the recipe if the only information is "I've done everything as the recipe said". I could have been not precise enough in the instructions, sure, but I do need more data. You need more data. Take your recipe and calculate it with bakers percentage. Not down what ingredients you're using. Describe the process. IF by now you still don't know what didn't work out, change one thing, note it down, note the result. And again. And again, till it works.

Because a baker needs to measure everything folks!

That could have been several blog posts.

Muffins are easy. So much flour (measure or weigh, it doesn't really matter), rising agent, salt, liquid,

Mix, then bake. Viola, muffins.

Except when doing something like making banana muffins... because you have to add a couple tablespoons of water at the end... sometimes much more, depending on the mushiness and water content of the bananas.

I find bread making to need to be taught by feel, and not by measure.

I deal in freshly ground flours, so, entire grain flours, and what i need to do is far more picky about conditions then i would if i used "all purpose white flour"

Like the gluten window you showed, it is necessary to know what it should look like and to know whether it is because of lack of kneeding or lack of water that you do not have things correct.

So, the best book on baking breads basically had a dozen recipes in the back, but basically it talked about one recipe and making it work.

The feel comes into play once you've built enough experience and you don't have to help others do the identical thing. The scale grows into your brain repetition after repetition.

With regards to the book: I have read both of the books mentioned in the text with a single rule - read everything except the recipe itself (only introductions and summaries for those). This was very helpful in building more understanding.

It felt so much as a whole thing I didn't want to split it up.

Wow, @breadcentric what a great read, so detailed and precise!

I have to admit, when I am making, soups, stews or the likes, I never measure; always a little bit of this and a lot of that.

But when it comes to making breads, I pretty much follow recipes to a “T”, otherwise, yes, you either have rocks on your hands or a dense ball of dough.

Thanks so much for the in depth explanation.

Congratulations - you put into this post everything (and more) that I spend years on different forums for and read through hundreds of pages of different books. Every bread baker should print it and put it into the pantry next to the flour! Thank you so much :)

Regarding tables: For my sour dough recipes and other breads that take a long time I make a time table like a military operation with counting the hours till it goes into the oven and between the steps in preparation. So when I need a bread at a specific time (let's say for a party) I can look at it and count back the time and see when the different work steps should be. And then decide whether I want to get up in the middle of the night to fold the dough;)

There is still one thing I don't fully get in the baking: every now and then one has to be ready to ignore all the guidelines and follow the gut feeling, accepting that things will not be reproducible.

For some it's the opposite way - follow gut feeling every time, measure roughly by watching progress, do things quickly and efficiently, with roughly consistent results. And it's also fine, I just can't make it this way :)

I go by gut with recipes I know, like my go-to white/toast bread. There I can mix some 405 or 550 or some spelt or some whole wheat. I know how it should look and feel at the different stations of preparation otherwise I wouldn't be free with ingredients.

Posted using Partiko Android

Yes, it is strangly hard to make something that people have made for thousands of years without apparent problems :D

And there are so many great breads and most of the world is unaware or even putt he name bread on something horrible, just because it is made out of wheat.

Well, making a basic bread is not a rocket science.

Making a bread one has imagined, being an effect of a lot of precise steps, in a reproducible way requires more effort.

So much information! I did the mistake with changing the flours and hoping that my bread would come out ok. How wrong I was :D

And finally I understand those numbers when I'm trying to get my flour in Germany :) all of sudden it does make sense!

Thank you so much for sharing. I will save your post to use it anytime I need some advice as it's great!

This is a really well built post!

A lot about baking. I really relate to the measuring part, as I'm creating small quantities of bread but it's hard to get amounts right when you're playing on less than 10 grams level..

And then some recipes ruin everything by using measurements like "Tablespoon" and "Cup". A deciliter is something I can still manage, but I feel bad about it.

I have a book from around 1920 from the east parts of then Polish territory, where flour for the bread is measured in buckets, amongst others.

I guess it's down to a common understanding between the author and the reader, but I couldn't find an information on the bucket volume in there.

What my wife suggested to me once is that if you make the same recipe over and over, you could spend let's say 30 minutes measuring all the ingredients and putting them into seal top bags and then just taking a bag when you plan to bake. It could be a huge time saver.

This post was shared in the Curation Collective Discord community for curators, and upvoted and resteemed by the @c-squared community account after manual review.

@c-squared runs a community witness. Please consider using one of your witness votes on us here

This post has received a 1.56 % upvote from @drotto thanks to: @siphon.

Excellent post.

I myself don't really like working in precise measurements cooking. Probably why I cook more than I bake. :P I've always known that the baking recipes aren't really as precise as they make out...good to know more about how and why when it comes to baking bread.

In the end it's about what works for you best. When it's my hobby baking I will always be more precise. When I need to magic up a heap of pancakes I will just mix things and start, check the first one, improve, check the second one, improve and I will never be able to repeat the result. A true once in a lifetime experience ;)

You are totally a baking geek 😄

I measure ingredients precisely but you do away more. This post will be my tomorrow read while waiting for my bread rises.

I start sour dough with while wheat. And I’m also interested in the books you mentioned. So many things to learn (that’s good!)

Thank you for sharing your precious knowledge!!