The Greatest Living Novelist (in my humble opinion)

Without a doubt, one of the highlights of my two and a half decades as a published writer, was being selected as a juror for the Neustadt Prize. This biennial award for international literature, considered one of the most prestigious worldwide, is also referred to as the "American Nobel"—because of its record of 30 laureates, candidates or jurors who in 42 years have been awarded Nobel Prizes following their involvement with the Neustadt Prize. Candidates for the $50,000 prize are chosen by an international jury of, at least, 7 writers-which I had the honor to be a member of, just a few years ago.

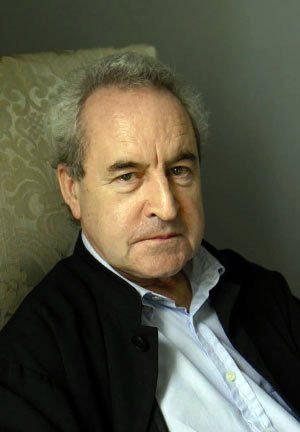

Being an Arab juror, I suspect that I was expected to nominate a writer from my part of the word for the Prize. But, my allegiances were to Literature & not Geography and, in good faith, I could not come up with a living Arab writer (other than, perhaps, Adonis) whose entire body of work I regarded as an outstanding achievement in poetry, fiction, or drama. I had to trust my instincts on this, and nominated an Irish novelist, whom I consider to be the greatest living prose stylist, and heir to my long dead masters whom I'd grown up reading, and emulating as a writer. I chose John Banville, and he nearly won (coming in at a very close second, after a rather tense tie-breaker). Below, is the case that I made for why I selected Banville.

THAT PARTICULAR INTENSE GAZE: AN APPRECIATION

The Irish writer John Banville is a novelist of ideas whose prose aspires to the condition of poetry. Whether meditating on the truths of art or science, investigating the nature of reality or mortality, or forever trying to pinpoint the elusive self, this modern master demands to be read slowly and thoughtfully. Of course, Banville is hardly unknown, but until he won the UK’s Man Booker Prize in 2005, for The Sea, Banville labored in relative obscurity for around three decades, his finely-wrought thirteen previous novels selling fewer than 5,000 copies in hardback. To be sure, this has something to do with his uncommercial concerns and purportedly “difficult” style.

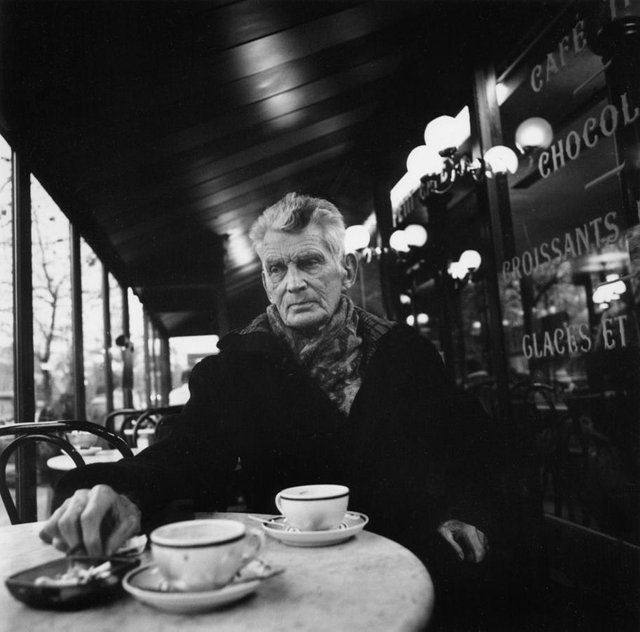

Like his professed mentor, Samuel Beckett, whom he has written about perceptibly and whose shadow is never far, Banville, too, for all his arsenal of jeweled words, seems always to be straining at the limits of the sayable. ("So much is unsayable: all the important things,” he writes in The Newton Letter (David R. Godine). Also, as with Beckett, it is not an ethical truth (moral, value judgment) that can be trusted, but an aesthetic one (form, language) that we return to time and again. Only describe might be the mantra here, as faithfully and truly as you possibly can. This is, at most, what the artist is capable of. “You cannot even speak about truth. That’s what’s so distressful. Paradoxically, it is through form that the artist may find some kind of a way out. By giving form to formlessness. It is only in that way, perhaps, that some underlying affirmation may be found.” This is Beckett in conversation, but it might as well be Banville.

Besides describing, there’s imagination—perhaps the artist’s version of compassion. In Banville’s morally ambivalent universe, it is failure of imagination that permits one of his sympathetic monsters, Freddie Montgomery, to take a life in The Book of Evidence. Passionate as Banville is about the life of the mind, the drama to be found in his work is, generally speaking, internal, as his articulate characters strive to eavesdrop on their soul’s dialogue with itself. In Eclipse, for example, one of his typically introspective male narrators, actor Alexander Cleave, retires from life and the stage to his childhood home to do just that: better overhear himself. When he turns outward, his ambitions are at once modest and profound; he is after the essence of things.

As Cleave sets about to study commonplace things—an open window, a chair, flowers—he finds “the actual has taken on a tense, trembling quality. Everything is poised for dissolution. Yet never in my life, so it seems, have I been so close up to the very stuff of the world . . .” This tremulous awe in the face of the ordinary is reminiscent of Rilke, who in the ninth Duino Elegy, asks: “Are we, perhaps, here just for saying: House, Bridge, Fountain, Gate, Jug, Fruit tree, Window—possibly: Pillar, Tower?” In so doing, Rilke does not believe he’s merely mouthing names, but almost mystically endowing things with a special life force ("such saying as never the things themselves / hoped so intensely to be”). Banville, also, shares in this concept of the artist as a sort of mystic. In an interview at Powells.com (April 5, 2010), he illustrates his “method” in these memorable words: “You know, the artist concentrates on the detail of the object until it blushes in the way the love object blushes when a lover gazes at it with that particular intense gaze. That is what art should do. It should make the world blush and give up its secrets.”

Style is not merely a superficial concern in Banville, it is how he conjures the secrets he is after. He approvingly quotes Henry James: “In literature, we move through a blessed world, in which we know nothing except through style, and in which everything is redeemed by style.” As a novelist slightly irritated with the form and limitations of the novel, Banville has defiantly expressed disregard for most aspects associated with it, professing “little or no interest in characters, plot, motivation, manners, politics, morality or social issue . . .” In their stead, it seems that his abiding interest is nicely suggested in the opening lines of Czeslaw Milosz’s magisterial “Ars Poetica”: “I have always aspired to a more spacious form / that would be free from the claims of poetry or prose.” This “spacious form” is one that Banville inhabits quite well in his oeuvre, which is rich, allusive, playful, and existential at the same time.

As a barely closeted aesthete, and also in his capacity as a long-time book reviewer (for theNew York Review of Books, etc.), it is evident Banville believes in the civilizing influence of beauty and literature. It was his stated duty, for example, as editor for the Irish Times, “to get people to read good books.” In fact, more than once, Banville has confessed: “The world is not real for me until it has been pushed through the mesh of language.” However, such an aesthetic sensibility is not antithetical to reality, but complimentary, in the sense Joseph Brodsky meant when he wrote: “Art is not an attempt to escape reality but the opposite, an attempt to animate it. It is a spirit seeking flesh but finding words.”

Which is why finding the right words is paramount for Banville. In further defense of the importance of style, here is Nietzsche—whom Banville quotes, often and admiringly, referring to him a “superb literary stylist.” Far from being a trivial concern, the philosopher writes: “Improving our style means improving our ideas. Nothing less.” And elsewhere, Nietzsche effuses lyrically: “Oh, those Greeks! They knew how to live. What is required for that is to stop courageously, at the surface, the fold, the skin, to adore appearances, to believe in forms, tones, words and the whole Olympus of appearance. Those Greeks were superficial out of profundity.”

Something of this paradox is at the heart of Banville, who claims only to concern himself with the world of appearances yet is clearly enmeshed in the mysteries of consciousness. This aesthete’s philosophy, being “superficial out of profundity,” seems at the root of his thought-tormented, solitary heroes. Mostly outsiders, these scientists, artists, murderers, spies, and actors are taunted by intimations of transcendence or transformation. In their desperate pursuit of clarity and understanding, they seek far and wide for, as he puts it in Kepler, “world-forming relationships, in the rules of architecture and painting, in poetic metre, in the complexities of rhythm, even in colours, in smells and tastes, in the proportions of the human figure.” But first they must wrestle with themselves, these unreliable filters of reality, and here is where the emphasis on style comes into play:

When we were children, we used to say of show-offs in the school playground they were only shaping; it is indeed something I never got out of the habit of; I made a living from shaping; indeed I made a life. It is not reality, I know, but for me it was the next best thing—at times, the only thing, more real than the real.

This is Cleave from Eclipse again, musing on his professional, and personal, tendency to fashion masks (“a making-over of all [he] was into a miraculous, bright new being”). The same desire for self-fashioning, or re-creation, could apply to Cleave’s fictional predecessors, such as Freddie Montgomery in The Book of Evidence or Victor Maskell in The Untouchable. In an aphorism titled, “One Thing Is Needful,” Nietzsche summarizes this art of living thus: “To give style to one’s character. A great and rare art. He exercises it who surveys all that his nature presents in strength and weakness and then molds it into an artistic plan, until everything appears as art and reason and even weakness delights the eye.” Of course, this aesthetic project extends past simply giving style to one’s character (or characters) and ultimately to life itself—which appears in need of order and harmony, amidst so much absurdity or chaos.

Throughout it all, there is no escaping the sheer pleasure of Banville’s singing prose—his wondrous-strange manner, which boasts a profusion of gifts and an uncommon sensitivity to the ineffable. We’re confronted with the work of a muralist and also a miniaturist, someone equally at ease tackling the large themes—time, memory ("The past beats inside me like a second heart,” he writes in The Sea), authenticity, alternative existences—as he is capable of devoting loving attention to the details that make up our world. We emerge from his novels, senses tingling brightly, somehow more aware of our possibilities. And Banville honors “the ordinary, that strangest and most elusive of enigmas” through his allegiance to indeterminacy, often content to leave mysteries unresolved, thrumming.

In justifying the existence of the controversial Western Canon, critic Harold Bloom states that a key facet to great writers “is strangeness, a mode of originality that either cannot be assimilated or that so assimilates us that we cease to see it as strange.” Banville, whom Bloom admires, is eligible by these standards as a distinguished heir to a tradition of great European prose stylists. As a novelist, he seems to write with his entire nervous system (rendering country light, for example, as “the hue of headaches” in The Infinities, and as readers we are deeply rewarded by paying close attention to his considered and concentrated writing.

© Yahia Lababidi

My Banville Appreciation appears in Rain Taxi: http://www.raintaxi.com/that-particular-intense-gaze-an-appreciation-of-john-banville/

(Images: Pixabay)

If you enjoyed this, you might also appreciate these previous posts:

Rising Syrian Writer Wrote Acclaimed Book While Driving A Cab

Thank you for such a wonderful article. John Banville is new name to me, but the way in which you describe his style has intrigued me enormously. A new author to follow up.

So glad you enjoyed it, @naquoya. A large part of why I write is to communicate enthusiasms and discoveryes, and finding Banville was like learning of a new star in the skies. The great thing is, he’s still alive and has some more books in him, yet! Happy reading 🤓

Whao, a Neustadt Prize juror! We really are lucky to have you here on steemit, Yahia.

Brilliant! This makes you wonder, again, why do we even try! But as T.S Eliot said and I love to quote, For us there is only the trying; the rest is not our business.

Amazing! Just amazing! And being superficial out of profundity, just terrific! This was a truly enjoyable read.

Thank you, for your close and enthusiastic attentions, my friend. I'm glad this piece resonated with you :)

Being on Steemit, for nearly a year, has been a humbling and rewarding experience—teaching this old dog a new trick or two. Good to get to know you a little better

_/|\_So, my friend, which of his works should I read first? My TBR list was in dire need of updating in any event.

The Untouchable is my first, so I have a soft spot for that. Writing is shudderingly good. Book of Evidence is a gem, as if Dostoevsky and Wilde had a literary love child! And Eclipse is a book of voluptuous mourning and profound interiority, really, first rate thinking/feeling.

I almost envy you, dear Inna @authorofthings, being new to Banville 🙇🏻

Thank you for another contribution, Yahia,

always enriching us with authors, writers, poets,.. and your own amazing writing style.

Your post has been upvoted by @arabsteem curation trail

And was also selected to our daily curation digest :)

Very happy you enjoyed it, and for the opportunity to share my writing and enthusiasms with the Arab community on @Arabsteem. Especially, grateful to be selected for your daily curation digest and to reach new readers, here :) Cheers, Yahia

Oh wow, Neustadt prize juror!

For me the greatest living novelist is Kenzaburo Oe, although I have not been reading his works since he won the Nobel (i.e. from 'Somersault' onwards).

Thanks, for reading, @petrmisan, and pointing me in the direction of Oe, who I intend to better familiarize myself with :)

great post

You read it in 2 minutes?