History of Christmas

History

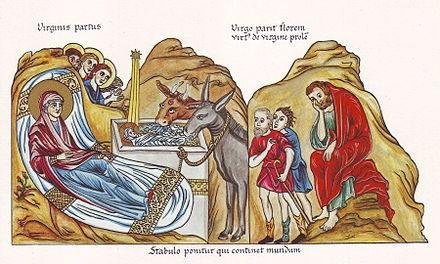

Nativity of Christ – medieval illustration from the Hortus deliciarum of Herrad of Landsberg (12th century)

The Nativity stories of Matthew and Luke are prominent in the gospels and early Christian writers suggested various dates for the anniversary. The first recorded Christmas celebration was in Rome in 336.[57][58] Christmas played a role in the Arian controversy of the fourth century, but was overshadowed by Epiphany in the early Middle Ages. The feast regained prominence after 800, when Charlemagne was crowned emperor on Christmas Day. Associating it with drunkenness and other misbehavior, the Puritans banned Christmas.[59] It was restored as a legal holiday in 1660, but remained disreputable. In the early 19th century, Christmas was revived with the start of the Oxford Movement in the Anglican Church, which ushered in "the development of richer and more symbolic forms of worship, the building of neo-Gothic churches, and the revival and increasing centrality of the keeping of Christmas itself as a Christian festival" as well as "special charities for the poor" in addition to "special services and musical events".[60] Charles Dickens and other writers helped in this revival of the holiday by "changing consciousness of Christmas and the way in which it was celebrated" as they emphasized family, religion, gift-giving, and social reconciliation as opposed to the historic revelry common in some places.[60]

Outdoor Christmas decoration

The early church was concerned with the death, resurrection and life of Christ. They essentially ignored the birth of Christ until Docetism and Gnostics asserted that Christ did not have a physical body. To assist in combating what the church considered heresy,[61] the Roman church established a date to celebrate Christ's birth, sometime in the 4th century. Other Christian churches had done so or would do within a century. The church's assertion of a physical body was also supported by the celebration of the Epiphany, established around the same time.[62][63][64]

Choice of December 25 date

In the 3rd century, the date of birth of Jesus was the subject of both great interest and great uncertainly. Around AD 200, Clement of Alexandria wrote:

“ There are those who have determined not only the year of our Lord's birth, but also the day; and they say that it took place in the 28th year of Augustus, and in the 25th day of [the Egyptian month] Pachon [May 20] … Further, others say that He was born on the 24th or 25th of Pharmuthi [April 20 or 21].[65] ”

In other writing of this time, May 20, April 18 or 19, March 25, January 2, November 17, and November 20 are all suggested.[8][66] Various factors contributed to the selection of December 25 as a date of celebration: it was the date of the winter solstice on the Roman calendar; it was about nine months after March 25, the date of the vernal equinox and a date linked to the conception of Jesus; and it was the date of a Roman pagan festival in honor of the Sun god Sol Invictus.

Solstice date

December 25 was the date of the winter solstice on the Roman calendar.[67][34] Jesus chose to be born on the shortest day of the year for symbolic reasons, according to an early sermon by Augustine: "Hence it is that He was born on the day which is the shortest in our earthly reckoning and from which subsequent days begin to increase in length. He, therefore, who bent low and lifted us up chose the shortest day, yet the one whence light begins to increase."[68]

Linking Jesus to the Sun was supported by various Biblical passages. Jesus was considered to be the "Sun of righteousness" prophesied by Malachi.[69] John describes him as "the light of the world."[70]

Such solar symbolism could support more than one date of birth. An anonymous work known as De Pascha Computus (243) linked the idea that creation began at the spring equinox, on March 25, with the conception or birth (the word nascor can mean either) of Jesus on March 28, the day of the creation of the sun in the Genesis account. One translation reads: "O the splendid and divine providence of the Lord, that on that day, the very day, on which the sun was made, the 28 March, a Wednesday, Christ should be born. For this reason Malachi the prophet, speaking about him to the people, fittingly said, 'Unto you shall the sun of righteousness arise, and healing is in his wings.'"[8][71]

In the 17th century, Isaac Newton argued that the date of Christmas was selected to correspond with the solstice.[35]

According to Steven Hijmans of the University of Alberta, "It is cosmic symbolism ... which inspired the Church leadership in Rome to elect the southern solstice, December 25, as the birthday of Christ, and the northern solstice as that of John the Baptist, supplemented by the equinoxes as their respective dates of conception."[72]

Calculation hypothesis

The Calculation hypothesis suggests that an earlier holiday held on March 25 became associated with the Incarnation.[73] Modern scholars refer to this feast as the Quartodecimal. Christmas was then calculated as nine months later. The Calculation hypothesis was proposed by French writer Louis Duchesne in 1889.[74][36]

In modern times, March 25 is celebrated as Annunciation. This holiday was created in the seventh century and was assigned to a date that is nine months before Christmas, in addition to being the traditional date of the equinox. It is unrelated to the Quartodecimal, which had been forgotten by this time.[75]

Early Christians celebrated the life of Jesus on a date considered equivalent to 14 Nisan (Passover) on the local calendar. Because Passover was held on the 14th of the month, this feast is referred to as the Quartodecimal. All the major events of Christ's life, especially the passion, were celebrated on this date. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul mentions Passover, presumably celebrated according to the local calendar in Corinth.[76] Tertullian (d. 220), who lived in Latin-speaking North Africa, gives the date of passion celebration as March 25.[77] The date of the passion was moved to Good Friday in 165 when Pope Soter created Easter by reassigning the Resurrection to a Sunday. According to the Calculation hypothesis, celebration of the quartodecimal continued in some areas and the feast became associated with Incarnation.

The Calculation hypothesis is considered academically to be "a thoroughly viable hypothesis", though not certain.[78] It was a traditional Jewish belief that great men lived a whole number of years, without fractions, so that Jesus was considered to have been conceived on March 25, as he died on March 25, which was calculated to have coincided with 14 Nisan.[79]

A passage in Commentary on the Prophet Daniel (204) by Hippolytus of Rome identifies December 25 as the date of the nativity. This passage is generally considered a late interpellation. The manuscript includes another passage, one that is more likely to be authentic, that gives the passion as March 25.[80]

In 221, Sextus Julius Africanus (c. 160 – c. 240) gave March 25 as the day of creation and of the conception of Jesus in his universal history. This conclusion was based on solar symbolism, with March 25 the date of the equinox. As this implies a birth in December, it is sometimes claimed to be the earliest identification of December 25 as the nativity. However, Africanus was not such an influential writer that it is likely he determined the date of Christmas.[81]

The tractate De solstitia et aequinoctia conceptionis et nativitatis Domini nostri Iesu Christi et Iohannis Baptistae, falsely attributed to John Chrysostom, also argued that Jesus was conceived and crucified on the same day of the year and calculated this as March 25.[82][83] This anonymous tract also states: "But Our Lord, too, is born in the month of December ... the eight before the calends of January [25 December] ..., But they call it the 'Birthday of the Unconquered'. Who indeed is so unconquered as Our Lord...? Or, if they say that it is the birthday of the Sun, He is the Sun of Justice."[8]

History of Religions hypothesis

The rival "History of Religions" hypothesis suggests that the Church selected December 25 date to appropriate festivities held by the Romans in honor of the Sun god Sol Invictus.[73] This feast was established by Aurelian in 274.

An explicit expression of this theory appears in an annotation of uncertain date added to a manuscript of a work by 12th-century Syrian bishop Jacob Bar-Salibi. The scribe who added it wrote: "It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day." [84]

In 1743, German Protestant Paul Ernst Jablonski argued Christmas was placed on December 25 to correspond with the Roman solar holiday Dies Natalis Solis Invicti and was therefore a "paganization" that debased the true church.[38] It has been argued that, on the contrary, the Emperor Aurelian, who in 274 instituted the holiday of the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, did so partly as an attempt to give a pagan significance to a date already important for Christians in Rome.[37]

Hermann Usener[85] and others[44] proposed that the Christians chose this day because it was the Roman feast celebrating the birthday of Sol Invictus. Modern scholar S. E. Hijmans, however, states that "While they were aware that pagans called this day the 'birthday' of Sol Invictus, this did not concern them and it did not play any role in their choice of date for Christmas."[72] Moreover, Thomas J. Talley holds that the Roman Emperor Aurelian placed a Sol Invictus on December 25 in order to compete with the growing rate of the Christian Church, which had already been celebrating Christmas on that date first.[41]

In the judgement of the Church of England Liturgical Commission, the History of Religions hypothesis has been challenged[86] by a view based on an old tradition, according to which the date of Christmas was fixed at nine months after April 7 [O.S. March 25], the date of the vernal equinox, on which the Annunciation was celebrated.[82]

With regard to a December religious feast of the sun as a god (Sol), as distinct from a solstice feast of the (re)birth of the astronomical sun, one scholar has commented that, "while the winter solstice on or around December 25 was well established in the Roman imperial calendar, there is no evidence that a religious celebration of Sol on that day antedated the celebration of Christmas".[87] "Thomas Talley has shown that, although the Emperor Aurelian's dedication of a temple to the sun god in the Campus Martius (C.E. 274) probably took place on the 'Birthday of the Invincible Sun' on December 25, the cult of the sun in pagan Rome ironically did not celebrate the winter solstice nor any of the other quarter-tense days, as one might expect."[88] The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought remarks on the uncertainty about the order of precedence between the religious celebrations of the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun and of the birthday of Jesus, stating that the hypothesis that December 25 was chosen for celebrating the birth of Jesus on the basis of the belief that his conception occurred on March 25 "potentially establishes 25 December as a Christian festival before Aurelian's decree, which, when promulgated, might have provided for the Christian feast both opportunity and challenge".[89]

Introduction of feast

As Christmas was unknown to the early Christian writers, it must have been introduced sometime after 300. Irenaeus and Tertullian omit it from their lists of feasts, and Origen writes that in the Scriptures sinners alone, not saints, celebrate their birthday. Arnobius can still ridicule the "birthdays" of the gods.[8] The first recorded Christmas celebration was in Rome in 336.[57][58] The feast was introduced to the Eastern Roman Empire after the death of Emperor Valens, who favored the Arian heresy, in 378.

In 245, Origen of Alexandria, writing about Leviticus 12:1–8, commented that Scripture mentions only sinners as celebrating their birthdays, namely Pharaoh, who then had his chief baker hanged (Genesis 40:20–22), and Herod, who then had John the Baptist beheaded (Mark 6:21–27), and mentions saints as cursing the day of their birth, namely Jeremiah (Jeremiah 20:14–15) and Job (Job 3:1–16).[90] In 303, Arnobius ridiculed the idea of celebrating the birthdays of gods, a passage cited as evidence that Arnobius was unaware of any nativity celebration.[91] Since Christmas does not celebrate Christ's birth "as God" but "as man", this does not necessarily show that Christmas was not a feast at this time.[8]

The fact the Donatists of North Africa celebrated Christmas suggests that the feast was established by the time that church was created in 311.[92][93] The earliest known Christmas celebration is recorded in a fourth-century manuscript compiled in Rome.[57] This manuscript is thought to record a celebration that occurred in 336. It was prepared privately for Filocalus, a Roman aristocrat, in 354. The reference in question states, "VIII kal. ian. natus Christus in Betleem Iudeæ".[58] This reference is in a section of the manuscript that was copied from earlier source material.[94] The document also contains the earliest known reference to the feast of Sol Invictus.[95]

In Eastern Christianity the birth of Jesus was already celebrated in connection with the Epiphany on January 6.[96][97] Epiphany emphasized celebration of the baptism of Jesus.[98] December 25 celebration was imported into the East later: in Antioch by John Chrysostom towards the end of the fourth century,[97] probably in 388, and in Alexandria only in the following century.[99] Even in the West, January 6 celebration of the nativity of Jesus seems to have continued until after 380.[100]

In the East, early Christians celebrated the birth of Christ as part of Epiphany (January 6), although Christmas was promoted in the Christian East as part of the revival of Nicene Christianity following the death of the pro-Arian Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. The feast was introduced at Constantinople in 379, and at Antioch in about 380. The feast disappeared after Gregory of Nazianzus resigned as bishop in 381, although it was reintroduced by John Chrysostom in about 400.[8]

Relation to concurrent celebrations

Many popular customs associated with Christmas developed independently of the commemoration of Jesus' birth, with certain elements having origins in pre-Christian festivals that were celebrated around the winter solstice by pagan populations who were later converted to Christianity. These elements, including the Yule log from Yule and gift giving from Saturnalia,[101] became syncretized into Christmas over the centuries. The prevailing atmosphere of Christmas has also continually evolved since the holiday's inception, ranging from a sometimes raucous, drunken, carnival-like state in the Middle Ages,[102] to a tamer family-oriented and children-centered theme introduced in a 19th-century transformation.[103][104] Additionally, the celebration of Christmas was banned on more than one occasion within certain Protestant groups, such as the Puritans, due to concerns that it was too pagan or unbiblical.[59][105] Jehovah's Witnesses also reject the celebration of Christmas.

Mosaic of Jesus as Christus Sol (Christ the Sun) in Mausoleum M in the pre-fourth-century necropolis under St Peter's Basilica in Rome.[106]

Prior to and through the early Christian centuries, winter festivals—especially those centered on the winter solstice—were the most popular of the year in many European pagan cultures. Reasons included the fact that less agricultural work needed to be done during the winter, as well as an expectation of better weather as spring approached.[107] Many modern Christmas customs have been directly influenced by such festivals, including gift-giving and merrymaking from the Roman Saturnalia, greenery, lights, and charity from the Roman New Year, and Yule logs and various foods from Germanic feasts.[108] The Egyptian deity Horus, son to goddess Isis, was celebrated at the winter solstice. Horus was often depicted being fed by his mother, which also influenced the symbolism of the Virgin Mary with baby Christ.

The pre-Christian Germanic peoples—including the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse—celebrated a winter festival called Yule, held in the late December to early January period, yielding modern English yule, today used as a synonym for Christmas.[109] In Germanic language-speaking areas, numerous elements of modern Christmas folk custom and iconography stem from Yule, including the Yule log, Yule boar, and the Yule goat.[109] Often leading a ghostly procession through the sky (the Wild Hunt), the long-bearded god Odin is referred to as "the Yule one" and "Yule father" in Old Norse texts, whereas the rest of the gods are referred to as "Yule beings".[110]

In eastern Europe also, old pagan traditions were incorporated into Christmas celebrations, an example being the Koleda,[111] which was incorporated into the Christmas carol.

Congratulations @waiyanphyo! You have completed some achievement on Steemit and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

Click on any badge to view your own Board of Honor on SteemitBoard.

For more information about SteemitBoard, click here

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP