Our Stories About Aliens Are Actually About Us

Josh O’Connor- autore

ETs don’t look like us. So why are they always depicted that way?

For as long as we’ve gazed at the stars, we’ve wondered whether there’s life up there. The heavens were originally the homes of gods. But as the Ancient Greeks developed science, their philosophers began theorizing that the stars also held creatures.

For almost 2,000 years, we thought of life in space to be pretty much like life on Earth. The Greek philosopher Anaxagoras proposed in the 5th century BCE that life was created by “‘seeds that littered the universe.” Other Greek philosophers like Anaxarchus and Epicurus likewise believed that life lay scattered among the stars. But none of them posited that humans would ever meet such lifeforms.

The first recorded depiction of extraterrestrials comes from the 2nd-century Greek philosopher Lucian. In “True History,” considered by many to be the first science fiction, the heroes are swept up by a whirlwind and taken to the moon, where they encounter mushroom men, cloud-centaurs and “dog-faced men fighting on winged acorns.” While certainly alien, all of these creatures are based on mashups of actual Earth life.

In Renaissance Europe, the church dominated everyday life, and people were in profound fear of going to hell. The church taught that Earth was the only world, and when Galileo and Copernicus argued otherwise in the early 1600s, they were condemned as heretics. So while astronomer Johannes Kepler weaves real astronomy into “Somnium” (1609), where the protagonist is transported to the moon, he’s careful to frame it as a dream. Still, 200 years before Darwin, Kepler realized that moon creatures must be different from Earth’s.

“If there are living creatures on the Moon … it is to be assumed that they should be adapted to the character of their particular country,” he writes.

But since Kepler believed the Moon was pretty much like Earth, his massive serpents, winged and otherwise, weren’t that different.

Francis Godwin also believed the Moon was Earth-like, so “The Man in the Moone” (c. 1620) describes bird species, trees and even humans — though importantly, all are many times bigger than their Earth equivalents. What’s more, the moon people praise Jesus. As pluralism — a belief in both the Bible and science — took hold, many stories described “a universe densely populated with rational extraterrestrials praising the providential workings of the Creator.”

The French satirist Cyrano de Bergerac (1619-1655) was an atheist. He attacked not only church dogma but human arrogance. ETs played a prime role in these criticisms. When his protagonist Dyrcona journeys to the moon in “The States and Empires of the Moon” (1657), it’s populated by giants like Godwin’s, who capture him and keep him as a pet. When he visits the sun, he meets changelings that “morph into birds, trees and human beings, until they are finally revealed as beings more perfect than man.”

The English philosopher Francis Bacon did believe in the superiority of man — the British man. His “New Atlantis” (1627) envisions a possibly alien world whose masters conduct genetic experiments on lower life forms. It was a reflection of Bacon’s vision of a utopian world driven by science, led by Britain. A genre called “planetary novels” sprang up, featuring European adventurers colonizing worlds.

“The expropriating British Empire expanded. Native colonial peoples were dispossessed, shot, poisoned and diseased. All this was made more possible by the ideology of Bacon.” -Mark Brake and Neil Hook, “Different Engines”

Satirist Jonathan Swift struck back at the bigotry of the planetary novels with his own subversive entry, “Gulliver’s Travels” (1726). The British hero encounters the first spaceship in fiction, the floating castle of Laputa. It’s run by a hyper-intelligent super-scientific humanoids — also fiction’s first “mad scientists.” With their superior wits and weapons, they terrorize the earthly lands beneath them. Swift was condemning Bacon’s science-fueled colonialism. More than a century later, the British writer HG Wells would take Swift’s concept of brutal aliens and run a mile with it.

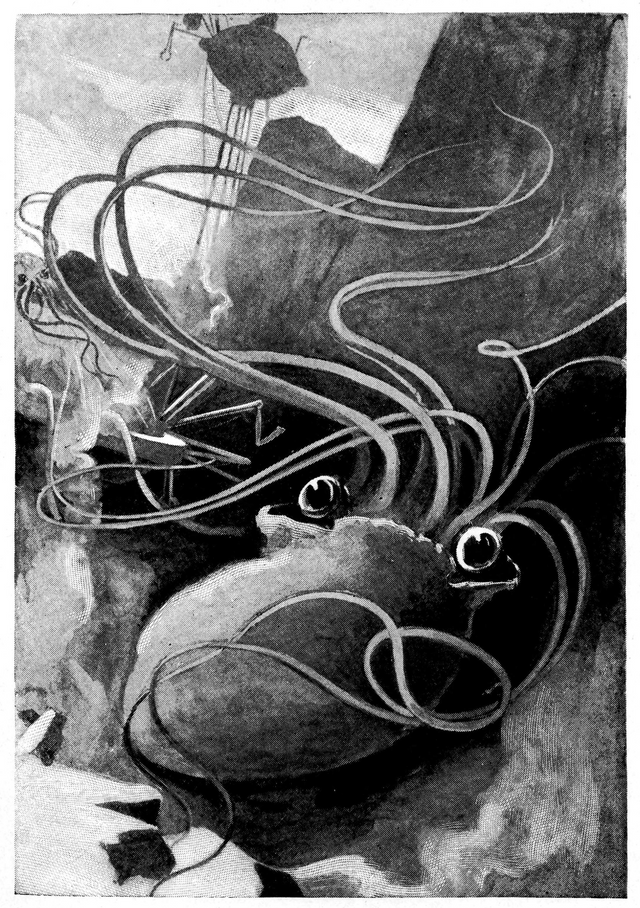

OK, we don’t have these on Earth: an illustration from ‘War of the Worlds.’ | PD

“War of the Worlds” (1898) was a prime example of the “invasion literature” that became popular after Prussia invaded France with cutting-edge weapons, defeating the world’s largest army in just two months. The invasion stoked Victorian anxieties that the globe-spanning British Empire had become complacent, and the xenophobic fear that foreigners — conquered or otherwise — posed a threat to Britain. Wells took “foreign” to a new level. The tentacled bodies and unfathomably advanced technology of the Martians bore no relation to humanity. Unlike demons or mythological monsters, they were not even connected with any pantheon of religious belief. The motivations behind their invasion were unknowable.

If Wells marked the break with human-centered depictions of extraterrestrials, it was Howard Phillips Lovecraft, a horror writer for pulp magazines during the 1920s, who shattered it completely.

An atheist and student of science, Lovecraft struck back at both religion and unscientific depictions of extraterrestrials. As the product of alien evolution, his ETs bore zero resemblance to humans, animals or religious deities. Sure, some people (often foreign, usually brown) worshiped them, but they were being duped!

There are no “gods” but only displaced extraterrestrial beings, the Great Old Ones, who journeyed to Earth many millions of years ago, bringing with them, disastrously, their slaves, called “shoggoths,” protoplasmic creatures that gradually overpower and defeat their masters. Deluded human beings mistake the Great Old Ones and their descendants for gods, worshiping them out of ignorance. -Joyce Carol Oates, “The King of Weird”

Take the shoggoth, “a terrible, indescribable thing vaster than any subway train — a shapeless congeries of protoplasmic bubbles, faintly self-luminous, and with myriads of temporary eyes forming and un-forming as pustules of greenish light.” Try drawing that. Many artists have tried, and it’s always different. Here’s one from a book of Lovecraftian extraterrestrials I wrote for a roleplaying game line:

At least you could see a shoggoth. “The Colour Out of Space” is just a color — and one that lies beyond the human visual spectrum. The Great Race of Yith do have describable bodies, but only because the minds of the “well-nigh omniscient” race have simply occupied the bodies of “cone-shaped beings that peopled our earth a billion years ago.”

The thoughts of the ETs were as unknowable as their forms. With incomprehensibly advanced technology or eons-old powers, Lovecraftian aliens killed humans by the score, but they did so impersonally, without explanation — sometimes just because we got in their way. Just as often they took over our minds or traded bodies with us for the pursuit of unknowable scientific ends. Lovecraft never illuminated their goals, science or beliefs. Unlike the invaders in “War of the Worlds,” we weren’t even sure the aliens particularly cared about taking over the Earth. We didn’t know what they wanted, because we couldn’t possibly understand them in human terms.

Lovecraft was dismissed as a hack in his lifetime and for decades after his death. But just as Edgar Allen Poe died penniless but came to underpin both the detective story and Gothic horror, Lovecraft’s works helped lay the foundations not only of modern horror but science fiction.

As sci-fi flowered, many authors took a similarly science-first view of what aliens might look like that’s consistent with the planet-wide, psychic organisms in books like Arthur C. Clarke’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” or Stanislaw Lem’s “Solaris” (both were made into great films).

The tradition of Earth-centric aliens has continued, though. In Robert Heinlein’s “Starship Troopers,” extraterrestrials are humanoid “skinnies” and insectoid “bugs” that are pretty unlikely to have evolved anywhere but on Earth. Most of the aliens in “Star Wars” had arms, legs and faces, and even spoke like us. “Star Trek” aliens are mostly humanoid too, though to their credit, the series also featured beings of pure energy. Even HR Giger’s terrifying designs for the “Alien” film series are humanoids mashed up with bits of centipede.

But Lovecraft stories — lurking in limited paperback print runs and moldering back issues of Weird Tales—had what Oates calls “an incalculable influence on succeeding generations of writers of horror fiction.” They include Stephen King (“The Mist”), filmmakers Joss Whedon (“The Cabin in the Woods”) and Guillermo del Toro (“Cronos”) and Matt and Ross Duffer — creators of the Netflix hit series “Stranger Things.”

The nature and appearance of the dimension-jumping monster in “Stranger Things” — and the “upside down” dimension that is a shadowy reflection of our own world — hew closely to Lovecraftian motifs.

Thanks for sharing .

we can mutually benefit following & upvoting each others post.

my blogs are related to Yoga ,Ayurveda ,Personal dev,The3 things & crypto.I am sure you will like them.

have upvoted above post .

waiting for you coming to my Small home of wellness .

okey :) lets do it )

@superlover

Nice Post!

Thanks for sharing this.

: ))