365 Days: 20 things I Learned from Traveling Around the World

Hello steemit and steemians

Travel for long enough and one day you wake up to realize: This is no longer a vacation, it’s your life.

365 Days: 20 things I Learned from Traveling Around the World

Over one year ago I quit my job and decided to travel around the world. This was both a dream 10 years in the making and one of the best decisions I’ve ever made [photo: night train from Belgrade to Sofia].

In the last 12 months I learned a lot about long-term travel, what I need to be happy, and how to survive outside of the US. Many of these things can’t be learned at home or in a book, and while reading about them on the internet can only get you so far, a lot of people have asked me to explain how I’ve done it.

Well, here’s part of the answer.

“There’s no substitute for just going there.”

My trip hasn’t been about sightseeing (although I’ve done that) as much as just being somewhere. The simple challenges of daily routine can be overwhelming: trying to eat, drink, and sleep in a place where nothing makes sense, you don’t speak the language, and where none of the basic comforts of home are available. It’s not easy, but if you want a fast-track to personal development, get on a plane.

When I was younger my dad often said ‘the hardest part is just getting out the door.’ And that may be the most important lesson of all: it’s too easy to get complacent at home and if you aren’t at least a little uncomfortable, you probably aren’t learning anything.

If you’ve already traveled extensively, you may get a kick out of this. If you haven’t, here are some reflections, tips, and advice about long-term travel on my one-year anniversary of life on the road:

#1) Most of the world’s people are friendly and decent.

Except for the French*.

Some stereotypes really hold up, but on average, most of the people I’ve met around the world are extremely polite, friendly, and helpful. They are generally interested why I chose to visit their home. They are eager to assist if it’s obvious I’m lost or in trouble. They’ll go out of their way to try to make sure I have a good stay in their country. And, contrary to what most Americans tend to think (see #3 below), they often don’t know much about the United States (or necessarily care).

Don’t be convinced before leaving that “everyone there is _______”. Show a modicum of respect to people and their culture and you’ll be blown away by what you get back. Try picking up a little of the local language. Just learning how to say ‘thank you’ can make a huge impact.

- Sorry, I couldn’t resist. To be fair, France is like everywhere else: most people are decent. It’s just that France has a particularly large proportion of bad apples the give the place a well-deserved reputation. I’ve met a lot of wonderful people in France but also a disproportionate number of assholes (not travelers generally, but residents of France). This isn’t based on a single trip nor is it restricted to Paris. Almost every non-French local in Europe agreed with me on this one.

#2) Most places are as safe (or safer) than home.

I remember confessing to my mother recently that I had a big night out in Budapest and stumbled back to my apartment at dawn. Her reaction was: “But don’t you worry about being drunk in a foreign country?”

Ha ha, not at all mom! I’ve never felt so safe!

The only place I’ve been violently mugged was in my home city of San Francisco. Many of the people I know there have been robbed at gunpoint, and on more than one occasion there were shootings in my neighborhood.

In one incident just a block away from my apartment (Dolores Park), a man was shot 5 times and somehow escaped, only to collapse about 10m from our front door. You can still see the blood stains on the sidewalk.

Turns out we actually live in a pretty dangerous country.

In over 365 days on the road, staying mostly in dormitory-style hostels and traveling through several countries considered ‘high-risk,’ the only incident I had was an iPhone stolen out of my pocket on the metro in Medellin, Colombia. I didn’t even notice and deserved it for waiving the damn thing around in the wrong part of town. Most people think that in a place like Colombia you’ll still get kidnapped or knocked off by a motorcycle assassin, but that’s not true. According to the locals I talked to (who grew up there), things have been safe there for at least ten years.

Caveat: This doesn’t give you a license to be stupid, and some places really warrant respect. Guatemala and Honduras, where there are major drug wars going on (and the Peace Corps recently pulled all of their volunteers), or Quito, Ecuador, where everyone I talked to had been robbed, are reasonably dangerous (I had no trouble in any of them).

In reality, based on the sort of mindless binge-drinking that happens in most travel hot spots, you’d expect travelers to get knocked off a lot more often. But if you pay attention and don’t do anything stupid, you’ll be fine.

#3) Most people don’t know (or care) what America is doing.

I think the whole America vs. the rest of the world debate has been summed up perfectly in this post:

10 Things Americans Don’t Know About America

I couldn’t have said it better:

Despite the occasional eye-rolling, and complete inability to understand why anyone would vote for George W. Bush, people from other countries don’t hate us either. In fact — and I know this is a really sobering realization for us — most people in the world don’t really think about us or care about us.

I’ve met people that didn’t even know that San Francisco (or California even) had a coastline (now there’s a sobering conversation for you. So much for thinking that’s the center of the world eh?).

One thing is true: Americans are not well represented on the travel circuit. It just doesn’t seem to be culturally important to us, unlike say, the Australians, who never go home.

#4) You can travel long-term for the price of rent and a round of drinks back home

My favorite question from friends at home has been: “how the HELL are you still traveling?”

Well, for what you spent at lunch I can live on for a whole day in Indonesia. That’s all there is to it.

– Average monthly rent for a shared apartment in San Francisco: $1100 per person.

– My average monthly expenditure during the last year of travel: $1200 / month*.

That’s $40 / day, and includes some ridiculous and totally auxiliary expenses. For example:

10 days of Scuba diving in Utila, Honduras – $330

Kitesurfing gear rental in Mancora, Peru – $100 for two days

Flight to Easter Island (50% subsidized by my dad) – $400

Acquisition of 4 Surfboards, + Repairs and Accessories over the year – $750

Purchasing a bunch of gear, like a new netbook ($380), wetsuit ($175), boardshorts ($55), camping gear ($100), a SteriPen water purifier ($125), summer sleeping bag ($55)

Riding the NaviMag Ferry through the lake district of Chilean Patagonia from Coyaiquhe to Puerto Montt ($200).

Taking a total of 7 nearly cross-continental flights (like Brussels=>Greece) during my 4 months in Europe.

And so on. I also went out, a lot, and spent way to much money on alcohol.

Before I left home, my original budget projection was $50 / day, which I would consider lavish in many parts of the world. In some places, I spent as little as $20 / day (including lodging, all meals, and booze) while living in relative luxury right on the beach. Generally, I shot for $30 / day which gave me a buffer of $20 for travel and miscellaneous or one-time expenses.

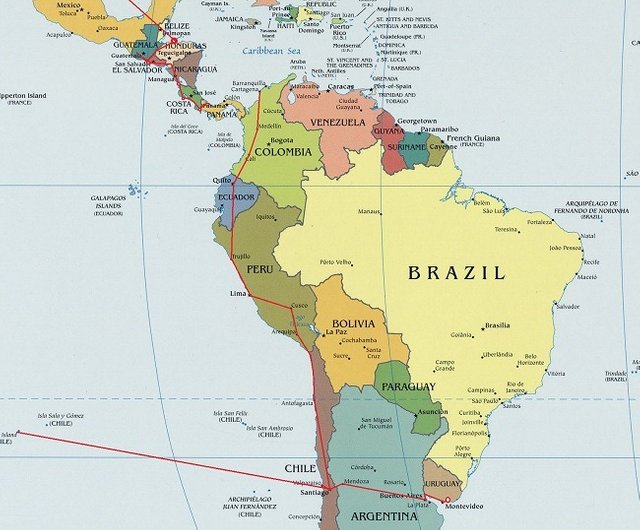

Countries visited on this budget: Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Easter Island (Chile), Argentina, Uruguay, Santa Cruz (California), North Shore of Oahu, Belgium, France, Spain, Germany, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Austria, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Turkey

Totals: 6 months Central/S. America, 2 Months USA, 2 months W. Europe and 2 months E Europe).

Obviously, some places are cheaper than others, like Guatemala, where you can get a room for $4 / night. You have to be a lot more careful in Western Europe, where I got a little bit loose with my budget and spent $2000 / month for two months. But I also spent less than $900 in the month that I biked (pushbike) through France.

You might be blown away by how cheap some ‘expensive’ places can be. The second cheapest hostel I stayed in (after Guatemala) was in Berlin, Germany, at €6 / night (~$7.43 USD). Beer in Prague was as cheap or cheaper than any other country I’ve been to (it was $1.43 for 0.5L in ultra-touristy downtown Prague). You can rent a decent downtown apartment in Budapest for $200 / month.

Bottom line: If you’re careful, you can travel on $1,200 / month or less. Rolf Potts, the author of Vagabonding (highly, highly recommended whether or not you’re planning to travel) claims to have circled the globe for years on $1000 per month. Budget $1,500 / month and you should be totally covered. You can do this even in Europe if you go slow, stay with friends or in cheaper hostels, fly on discount airlines (as opposed to taking the train), cook or eat street food, and don’t buy booze at the bar (which I did and somehow survived).

The best budget rule of thumb I’ve learned (can’t remember the source) is to take the price of your nightly accommodation and triple it. That will be about your daily minimum to survive, so $30 / day where a hostel runs you $10 / night.

*Note that my monthly total budget does not include transcontinental airfare (like USA=>Europe) which was free see How I flew around the world for $220 . Since I typically travel overland and all flights are one-way tickets I haven’t flown as much as you’d expect.

#5) Saving for a big trip is not as hard as you think.

Most people think I’m rich because I’ve been traveling for a year. What they don’t realize is that, although I didn’t leave at the time (this was 5 years ago), I was able to save enough money for this trip within a year and a half of graduating college.

My first salaried job paid $29,000 / year–not exactly ballin’ by US college-grad standards. But by pretty ruthless budgeting I was able to save $1,000 a month for the 15 months I worked there.

Guess what, that’s $15,000 or 12.5 months of travel at $1,200 / month.

Are there sacrifices to be made? Of course, but it’s worth it.

Btw, I am by no means the first person to discover or write about travel budgeting. This post is from 2009: Travel full-time for less than $14,000 per year . Don’t think it’s just us either, because all of these people

are writing about it.

I plan to write more about how to save money in the future

#6) In most places, moving around is incredibly easy.

I rode buses from Honduras all the way to Uruguay. With a surfboard. And it was a cinch.

Unlike the independent car culture of the US, people all over the world rely on some kind of bus service to get around.

In most places you can get from anywhere to just about anywhere else, and most of the time it doesn’t take more than a few minutes to figure out. Generally (outside the middle of peak tourist season in popular places) I haven’t bothered with reservations or pre-planning transportation routes. I just show up at the bus or train station and go.

I’ve ridden buses for hours into the middle of the Costa Rican jungle as well as through BFE in the Northern Chilean Andes. There’s almost always a group of locals who needs to get to where you’re going too. And if there’s no bus you can always hitchhike (this only happened once or twice on my entire trip).

It’s an eye-opener to see how some of the poorest countries on earth can still provide better public transportation than San Francisco.

In places like Europe and SE Asia you also have the opportunity to take advantage of discount airlines like RyanAir and EasyJet . I flew across Europe 7 times in 2 months for less than $120 that way.

#7) Every pound over 20 makes life worse.

There is virtually no reason to carry more than 20lbs (~9kg) of gear unless you’re going on a major trek or you have some serious sporting event in mind (like multi-day backpacking or cold weather sports). If you’re traveling in the summer you can get by on even less.

Here’s the first key: Try only to do one thing on your trip. If you are hiking, just hike. If you are surfing, just surf. If you’re party backpacking and staying in hostels, just do that. Packing for every possibility is suicidal. You just can’t carry street clothes and backpacking gear in the same pack and expect to not have a million tons of crap.

I’ve travelled the last year with a carry-on sized 30L day-pack made for climbing (this means it’s made to properly handle weight). Right now, it’s only 2/3 full and loaded with exactly 20lbs of gear (which in my opinion is still too heavy). But I have some serious accessories in there including 3lbs of surfing equipment (for Indonesia), a 3lb laptop, as well as a GoPro video camera (0.5lb).

When most people pack for a trip, they make a list of things to pack and then try to figure out how to fit it all in. But the best way to choose a backpack is to find the bag you want to carry and then see what you can fit inside. Make sure the pack doesn’t weigh more than 3lbs by itself.

If you can get to less than 15lbs (~7kg) it will change your life. Imagine getting to a location and being able to walk around and site-see with all your gear. Incredible.

This is the other key: pack the 20% of gear and clothing that will cover 80% of possible travel scenarios (yet another manifestation of the 80/20 rule ). If you end up saying “I might do _____” then get rid of it. Don’t take anything you won’t use with relative frequency unless it’s really expensive or hard to find on the road.

Get rid of everything you possibly can before you set out, and don’t be afraid to donate things or send them home along the way. Oh, and the easiest way to figure out your pack weight? Buy a cheap fish scale from Amazon.com.

A small pack also allows you to have a carry-on bag, even on super small planes. I can’t understate the importance of this.

Bottom line: Trust me, the longer you travel the less you want to carry.

Bonus: Here is my 2013 Round the World Trip pack list.

#8) Long-term travel is not a vacation (it’s a full-time job).

After my first 6 months of traveling I went home for a break. To the surprise of my friends, I was completely spent, exhausted, and didn’t want to do much of anything.

“But you’ve been on vacation, you should feel great!”

Right. I guess you missed the 22 hour bus-ride where we took turns puking in the back because of altitude sickness and pisco-induced hangovers. Or maybe you didn’t make it to the last 15 hostels where sleeping before being black-out drunk is just not an option. (Sounds glamorous, doesn’t it!)

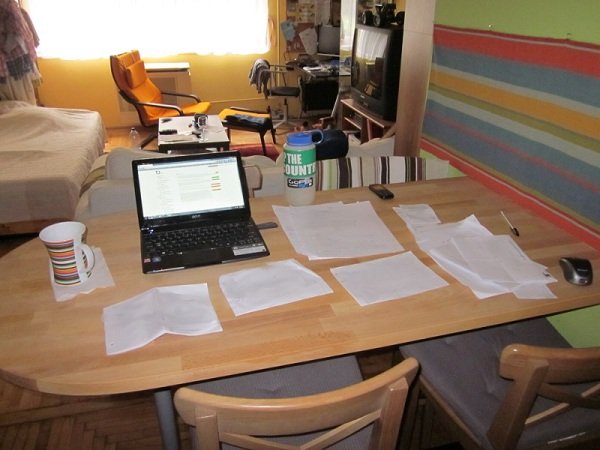

Planning and logistics also take an incredible amount of time and effort. Most downtime spent in a place when not sight-seeing is typically sucked up in researching the next destination, making reservations, planning logistics, and going through the dreaded ‘time budgeting’ process where you decide what you can reasonably see in the time available (and what you have to cut out).

Overall, it’s exhausting, and a great reason to consider traveling slowly (more on that later).

If you move quickly, don’t have any illusions about all the things you’re going to ‘get done’ in your down-time. Take a good book and just travel, that’s it.

#9) ‘Travelers’ and ‘Tourists’ are different.

You know what I mean.

Tourists exchange money for pre-packaged experiences. They consume experiences and move on without engaging with the local culture.

Travelers are there to see things, not buy them.

Travelers tend to be more involved. They may stay with locals, hang out with locals, try to learn the language, or just plain move slowly enough to really live and be where they are.

Sometimes I play ‘tourist’ but that doesn’t mean I see myself as one.

#10) Don’t worry about traveling alone (it’s better).

Although I’m a solo traveler I haven’t spent much more than a handful of days on the road alone. That’s because you meet people everywhere: in hostels, on buses, trains, planes, restaurants, trail-heads, monuments, etc. If you’re doing a standard travel circuit you’ll see the same people over and over again (most people don’t leave the Lonely Planet itinerary), and it isn’t uncommon to fall in with a large group of people who are all going the same way.

It’s so easy to meet people that I’m often stuck with the opposite problem: trying to get away from everyone. While I love all my new friends I need some downtime every so often.

Most travellers are uncommonly interested in meeting new people. That’s one of the big reasons they’re on the road. A simple ‘where are you headed’ has often turned into a new travel partner for weeks. And when it stops working you simply set off on your own again.

Afraid to go it alone? Don’t be. Go the the first big city in your destination country and hang out in the hostel lobby for a few days. I promise you’ll make new friends. This is why you should also stay in hostels. Don’t be afraid of sharing a room. It’s a small trade-off for the amazing people you’ll meet.

#11) Movement can be addictive (and this is not necessarily a good thing).

The ‘traveller’s rush’ that hits you upon arrival to a new place is like a drug. And like a drug, the more you expose yourself to it the more you want.

This can mean moving too fast or skipping out on places just to experience the ecstasy of arrival again. The results are obvious: less time in places you thought you wanted to see and ultimately, burnout. The tendency to try to cram more places into an overpacked schedule is often hard to control.

One trick I’ve found to deal with this is to have a minimum stay: 3 nights in every destination. This is enough time to see the place, relax, and get sorted before the next stop. It also means you’ll have to cut out some places if you’re tight on time. While I’ve had great one-night stops before (I’m looking at you, Belgrade) it isn’t sustainable or desirable to do too much of this.

Of course, some places aren’t what you expected either. If that’s the case, get the hell out of there and spend more time in a place you want to be.

#12) Don’t bank on paradise.

Keep your expectations in check.

This isn’t easy, since you really want that place you’ve been dreaming about to be paradise. But like anything else, high expectations are a recipe for disappointment.

I spent 5 years in office jobs dreaming about getting back to Utila, the magical Scuba party-island off the coast of Honduras. When I finally got there, I was ready to leave after a week.

Turns out I didn’t really care about Scuba-diving as much as I thought, and there’s only so much you can do on a tropical island before you go nuts. At that time I also had new aspirations and a new skill: surfing. I ended up heading to El Salvador to surf some of the best waves of my life.

Expectations can also make or break a place. Most of the places I knew nothing about before arriving blew my mind. Most of the places I had high expectations for utterly failed to impress me (except for Chicama, the world’s longest wave, and Rome).

The other thing is that as you go through life the rules are always changing. By the time I arrived here in Bali–which has been a dream and one of the pinnacles of the trip–I had a small but growing online business that had become my #1 priority. Instead of rushing off to some deserted beach hut and surfing all day I’m obsessed with trying to find a place to live where I can get to fast internet at least a few times a week. Say what you will, but my priorities have totally changed (at least for the moment).

It also turns out that a lot of Bali is a tourist nightmare from hell. Or maybe it’s just getting harder for me to be as impressed by anything.

Also: Take recommendations with a grain of salt. Another person’s paradise might be your personal hell, and vice-versa. A close friend of mine thinks tropical beaches are the reason for existence. Well, unless there is wind or waves on them I’ll crack up after 3 days. Getting stuck on a deserted tropical island is my definition of hell-on-earth.

#13) Traveling doesn’t get ‘traveling’ out of your system.

If you’ve got this bug it’s not going away (sorry), but the obvious question is: why are we trying to get traveling out of our system, anyway?

Rolf Potts did a great job in Vagabonding of justifying not just travel as a lifestyle, but also a lifestyle that makes travel a non-negotiable ingredient. Whether that means saving for a big trip or just taking a few weeks a year the important thing is to make room in your life to keep traveling.

I was actually told on this trip ( 😉 if you’re reading this) that I needed to stop screwing around and ‘grow up.’ I think in our culture that means going back to the ‘real world’ of office jobs, succumbing to general complacency, and trying to enjoy two weeks off a year.

If that’s the case you can count me out.

The world is just too big and interesting to not be exploring.

#14) Eventually, you will need something real to do.

Most people think that I’ve spent the last year sipping Mai-Tais on the beach somewhere. Well, I tried that and after 4 days I started to lose it.

The sad and somewhat surprising truth about the myth of the deserted tropical island paradise is this: there is nothing to do on a deserted tropical island. As Harrison Ford drunkenly slurred once in that terrible but entertaining movie, ‘Honey… it’s an island. If you don’t bring it you ain’t gonna find it here.”

Despite popular belief, most people can’t just sit around doing nothing for an extended period of time. Especially Type-A American folks who I’ve been told are ‘goal-oriented’ and always trying to ‘get things done.’ It might be a cultural thing, but it’s more likely just human nature to want to be involved in something larger than yourself. (This also, by the way, is the death knell for the whole concept of retirement, as articulated so well in Tim Ferris’ 4-Hour WorkWeek).

The point of quitting a job to travel around the world is also not to do nothing, it’s to do something else. As Tim Ferris points out, ‘idle time is poisonsous,’ and believe me, when you’ve cut your ties with conventional society you’re going to have a few moments of serious self-flagellation. The endless ‘what I’m doing’ and ‘why am I doing this’ loop.

It’s true that the feeling of wanting to build/create/be a part of something can be deferred since traveling itself is a full-time job, and that simple fact can keep you satisfied for a long time. But after 6 months of moving around I was astonished to discover I was actually bored. I mean, really bored. There are only so many days that you can walk around looking at things, go to the beach, and party all night without starting to think that something’s missing.

What it boils down to is that eventually you’ll need need a project. Whether that means studying, concentrating on a sport, volunteering, working somewhere, starting an online business, or whatever, eventually you’ll have to find a creative or intellectual outlet to keep yourself sane. Which brings up the next point:

#15) Long-term happiness is a pretty complicated emergent property that has little to do with money.

I will probably kick myself later for publishing this, but what the hell, here goes:

If you studied any chemistry in school you may remember the concept of emergent properties: the difference between the dining-room table and this computer screen is simply the right mix of a bunch of elements. Put together the right pieces and the product spontaneously emerges from the matter it’s composed of.

Similarly, in my experience happiness is not derived from a single point source (although it can be temporarily) like a sudden infusion of cash or arriving at your dream destination. Instead, it takes a lot of things working in concert to keep me happy: it’s really the emergent property of a network of variables.

Unfortunately, most people seem to forget the network effect and focus on a single variable, like money. Sure, money can allow you to do things, but once basic needs are satisfied the correlation between money and happiness seems to drop off a cliff.

A lot of people defer things they might otherwise pursue for the big payout dream. The ‘if I only win the lottery’ or ‘when I sell my company for $10 million’ routine. The problem with the fantasy, besides the obvious deferral of really having to come to terms with what you want to do in life, is that while a big payout would certainly increase the options available to you, but that is not necessarily a good thing. I won’t elaborate on this too much further here, but having more options has actually made me less happy in the past, as was so well articulated in The Paradox of Choice.

And here’s another punchline: most people whose luck or life-stage has allowed them to not be required to work seem to choose to anyway. I know a guy who retired at 26. What does he do now? Runs a firm for fun.

Think $10 million in the bank is going to make you happy? Well, good luck with that.

While I can’t speak for everyone, I’ve learned that I need the nearly perfect concert of 3-4 major variables before I can say that I’m ‘really happy’.

These have very little to do with money:

- Health: Not just injury or disease-free but fit and functional for everything I want to do. That could mean anything from just feeling good in the morning to being able to easily run 5 miles.

- Wealth: I’m not talking about money, but the reinterpretation of ‘wealth’ as the free time and means to do what you want to do. In my experience, control of my time is the key, and as long as I have enough money to cover basic expenses I’m happy.

- Relationships: In major cross-cultural studies published by the WorldWatch Institute, happiness has often been primarily attributed to breadth and depth of social connections. ‘Nuf said.

- Productive/Creative Outlet: As discussed above, I need something to learn, to do, or to build.

If this sounds cliche or too simple, try sitting on a beach somewhere and wonder why you’re not happy for a few weeks. It’s easy to forget the most basic things in life.

(The funny thing about having four simultaneous requirements is the violation of Sun Tzu’s Art of War: Never fight a battle on multiple fronts. Maybe you’ve figured it out already, in which case I’d love to talk to you about it, but whenever I get two things in order the third one drops out of the sky.)

#16) When you challenge a person’s assumptions it can really piss them off.

People get angry when I tell them you don’t have to buy into the system, that you can travel the world and do anything you want if you’re up for it.

The problem is that this statement challenges the basic assumptions that people have invested in over their entire lives–every decision, every action, every goal has depended on the stability of this conventional framework.

As I understand it from my limited study of neuroscience, these kinds of assumptions are firmly rooted in the brain’s neural network, and our cognitive framework (borrowing heavily from George Lakoff here) really doesn’t like being fucked with.

Just think about how hard it was the last time you tried to change a serious habit. The first day you try something new it can be physically painful because there’s a strong emotional response to resist change. Think also about the last time you had an argument about politics. Why is so much anger involved? Because you’re both challenging thought patterns that are too well established to change easily (it’s not air in there, but a real physical network of cells) .

Lakoff at one point wrote that the neural framework is like a net: if you offer something up radically different from what a person expects it might just slip through. It’s almost like they can’t even process what you’re saying to them.

It’s also hard for people to imagine anything different from their experiences. Take the notion of precedence (hat tip to Dan Andrews ):

before the 4-minute mile was broken it was thought to be physically impossible. That is, until Roger Bannister Roger Bannister

ran a mile in under 4 minutes. Within two months two more runners had achieved the same feat, and whole slough of runners soon followed.

When you defy the status quo (even when you don’t make a big deal out of it. cough) you implicitly (although unintentionally) suggest to people back at home that their lives are based on a faulty assumptions. Don’t expect people to take this well, or to care or understand what you’re doing if you decided to cut out. They might get pissed off, the might act like you don’t exist, or they might actively call you out.

You can’t convince them that it’s the right thing to do either, because in all honesty, we all have a different idea of what the good life is.

#17) Travel slowly: Save money, avoid burnout, do more.

Going slowly is the key. The more time you have the more money you can save, for two major reasons:

- Large expenses like airfare get averaged out over the course of cheap days staying in one place, and

- You can take advantage of special opportunities, like cheap flights or sleeping on a friend’s couch.

I talked to one girl who flew around Europe just on discount airlines like RyanAir and EasyJet. She’d simply log in and see where the cheapest flight next week was. “Guess I’m going to Romania!” Not something you can do easily on an itinerary.

The most expensive part of traveling for me has typically been moving from point A to point B. Traveling like a maniac can be a lot of fun, but you’ll save money and get to really know places if you take your time.

#18) You can’t work and travel at the same time.

For the remote-work inclined…

Ok, you sort of can, you just won’t ever get nearly as much done as you want to.

Let me clarify this for the uninitiated: obviously, you can work in the places you travel to, eg working as a SCUBA Divemaster or a Kiteboarding instructor, but my focus here is on location-independent internet work.

At this point I’ve worked all over the world on my laptop, and in order to get shit done I have to hunker down in one spot for at least a week. Try building/fixing things/growing an online business on the road and you’re going to just get irritated when you can’t finish anything in the 2-4 hour block you’ve set aside.

You also have no continuity if you’re constantly moving around. Dan Andrews of the Lifestyle Business Podcast nailed it when he said ‘you’ve got to find your 5 hours.’ All 4-Hour Workweek fantasies aside, if you want to build something you’d better find that 5 hours (or more) each day.

If you’re going to travel, then just travel. There are sights to see, spontaneous adventures to be a part of, and all kinds of unexpected things that happen. Aren’t you traveling to take advantage of those?

But when you’re going to work, just work. I think Tim Ferris really hit it with the concept of mini-retirements: the idea of focusing 100% on one thing at a time is the only way to make significant progress. Work for 1-3 months, then take a mini-retirement for 1-3 months (depending on what you’ve got set up for yourself. More on this later).

#19) When everything gets irritating, it might be time to head home.

I’ve had this experience more than once: a nice local is trying to help me but can’t understand what I’m asking for. I can feel my impatience rise and I notice my voice gets that “what the fuck is wrong with you” tone.

Then I remember: this isn’t home. People don’t speak English. Don’t expect anything to operate on your schedule. It’s not your country anyway, jackass.

This is usually the first sign of burnout, and usually means it’s time to find a cheap place to relax or time to book a flight home.

If you start really missing hot showers, strong coffee, Mexican food, or climate control, it might just be time, but….

#20) Long-term traveling can teach you more than almost anything else

About yourself, about life, about what you need to be happy. It also really highlights just how different home is from everywhere else, especially when you start to get a large sample size to compare it to.

For some, this can mean going home with a heightened perspective. For others, it may mean never going home. For everyone though, long-term travel will change your life.