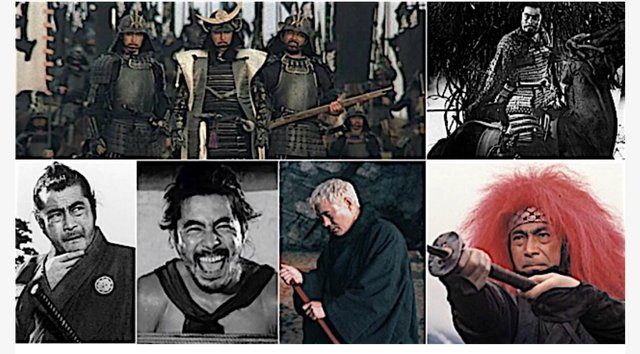

The 10 Best Samurai Films

The 10 Best Samurai Films

The armor and swords, the reverent

attitude and the reputation for supreme competence in warfare are all pretty impressive, but they don’t get to the heart of it. I believe it might be that at the core of every samurai is the code of bushido, the feudal Japanese equivalent of chivalry, with its one edict above all else: If the time should call for it, protect your lord with your life.

That self-abnegation

in service of something greater than oneself is thequestion at the heart of the works of generation after generation of directors as they revisit the samurai film. And it’s why we’re so excited to present Paste’s list of the 50 Best Samurai Films of All Time.

The samurai weren’t just warriors in colorful armor, but a whole societal class that arose to support the mounted archers who dominated the battlefields of medieval Japan. Most of the movies we’re looking at here occur after the rise of the shogunate—a central government based on a military dictatorship run by the shogun, rather than the emperor. The Muromachi Period encompasses the bulk of the movies in this list, but this part deals with the handful that occur in earlier times, before the ceaseless age of war that followed. For the purposes of our list, here are the films dealing with samurai before the rise of the shogun (and the horrific century of bloody civil war that followed).

- The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail

Year: 1945

Director: Akira Kurosawa

1-The-Men-Who-Tread-on-the-Tiger.jpg

We’ll be hearing much more from Akira Kurosawa throughout this list, so it’s worth it to have a look at one of his earliest films—one created as the United States took over Japan in the wake of the Second World War. This film was actually censored by U.S. officials for a number of years for its portrayal of samurai. It’s hard to imagine it being considered so offensive. The slim 60-minute movie tells a story set in A.D. 1185, when Japan’s rule truly went over to the shogunate system. The brother of the shogun tries to escape the latter’s attempts to have him arrested and killed, but his flight to safety requires that he and his six loyal samurai dress as Buddhist monks and attempt to bluff their way past suspicious guardsmen.

That’s about all there is to the story, which unfolds across just three locations and mostly focuses on the deep tension of the young lord’s retinue as they desperately bullshit their way past the shogun’s border patrol. What’s interesting is the wealth of Kurosawa hallmarks that any fan of his will recognize—the bumbling/helpful/mugging peasant, the tension between propriety and pragmatism, wide shots that take in the movement and emotion of many actors all at once contrasted with the close-ups that focus solely on the face of one principal character while no dialogue is spoken and yet everything comes across. Kurosawa would go on to hammer out decade after decade of indelible film classics and indispensable samurai films. Check out this short meditation to see how much he already knew 15 years before he even made Yojimbo. —Kenneth Lowe

- Gate of Hell

Year: 1953

Director: Teinosuke Kinugasa

1_Gate_of_Hell.jpg

What does it mean to be a good man? Does it mean unwavering fealty to your lord and land, an indomitable will to carry out your duties despite risk to your own safety? Does it mean devotion to your wife, and loyalty to her above all others? What happens when the first man grows jealous of the second man? In Gate of Hell, goodness is put to the test when a supposedly good man, the samurai Morito (Kazuo Hasegawa), falls in mad, impassioned love with Kesa (Machiko Kyo, best recognized for her stellar work in Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon), and so forces her to help him plot the death of her own beloved husband, Wataru (Isao Yamagata). Wataru, in stark contrast to Morito’s stereotypically macho posture, damn near worships his wife but never quite strikes us as a match for Morito’s masculine strength. All the same, he proves the better of the two by modern and even archaic definitions of manliness, while Morito proves himself to be something of a monster in spite of his martial virtues. Gate of Hell, one of Japan’s very first color films, is a gorgeous, trim, brisk picture, but more than its imagery and choreography, what sticks with me about the film is its concise, muted dissection of what honor and manhood are really supposed to be about. —Andy Crump

- Rashomon

Year: 1950

Director: Akira Kurosawa

2_Rashomon.jpg

What you get out of Rashomon likely reflects what you bring into it, but it might help to bring a basic grasp of cubism to the proceedings. When you hear the word “cubist,” your brain probably goes right to Picasso and Braque, but in cinema it ought to head straight to Kurosawa, who in essence gave birth to the movie version of cubism with Rashomon by performing a feat as deceptively simple as filtering a single narrative through multiple character perspectives; the more Kurosawa filters that narrative, the more the narrative changes, until we can no longer determine which to trust and which to write off. In the trial that comprises the bulk of the film’s plot, who is telling the truth? The bandit, the man accused of murdering a samurai and raping his wife? The wife? The samurai himself, summoned to the trial via spirit medium? Even when Kurosawa generously reveals what actually happened when the bandit crossed paths with the samurai and his wife via the post-trial testimony of a humble woodcutter, we’re still left to wrestle with the question of who, and what, we should believe. Kurosawa’s technical mastery is always awesome to behold, but in Rashomon, it’s his gift for utterly blurring reality that dazzles most. —Andy Crump

THE AGE OF CIVIL WAR | 1460s – 1603

By the mid-14th Century, the Ashikaga shogunate had come to rule Japan’s central government. In A.D. 1467, the Ashikaga entered into a 10-year war with other clans seeking to dislodge it, kicking off an age of civil wars that totally fumbled the ball and essentially robbed Japan of central governance. A system of violent, treacherous feudalism arose that created a sort of golden age of the samurai. Sengoku Jidai—this age of civil war—lasted a blood-soaked century and a half. Films set in this period feature massive armies clashing on horseback, devious clan warfare and intrigue, castles under siege, and earth-shattering historical epics written in noble blood.

- Throne of Blood

Year: 1957

Director: Akira Kurosawa

3_Throne_of_Blood.jpg

Kurosawa’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth is more than merely that, even if English majors will call each plot point before it happens. Toshiro Mifune stars as Washizu, a loyal samurai retainer driven to ambition and then ruin after receiving a prophecy from an evil spirit while wandering the aftermath of a decisive battle. Informed by Japan’s theatrical traditions—bold and exaggerated gestures, facial expressions, and movement—it’s an interpretation of a Western story that fits into its Eastern setting and style as if it always belonged there. The stark black-and-white photography Kurosawa employs here, more even than his better-remembered samurai films like Yojimbo or The Seven Samurai, demonstrates how much care he puts into each shot, whether it requires the exact timing and coordination of hundreds of extras, intricate blocking as a single character succumbs to madness or despair, or framing a motionless evil spirit leering menacingly in the midst of a fog-shrouded forest. Throne of Blood is the rare film that can function as both a love letter to its source material and a unique work of art in its own right. And it puts other, lazier adaptations of Shakespeare to shame, too. —Kenneth Lowe

- The Hidden Fortress

Year: 1958

Director: Akira Kurosawa

5_Hidden_Fortress.jpg

It’s sort of unfortunate that The Hidden Fortress is chiefly known in the West for being one of George Lucas’ inspirations for Star Wars, because there’s much, much more to love about this rousing adventure film. Initially told from the point of view of two bumbling, quarrelsome civilians (Minoru Chiaki and Kamatari Fujiwara) who are lured into the thick of a war zone by the promise of gold, the story soon finds them running afoul of two opposing clans. But you’ll unquestionably recognize some of the story beats: There is a noble samurai general (Toshiro Mifune, galloping full tilt to slay opponents and engaging a rival in an honor duel with spears) and a princess in disguise fighting to oppose an overwhelming army (Misa Uehara). Kurosawa’s camera work, especially in the scenes leading up to combat and those showcasing the explosiveness as it unfolds, is as sharp as ever. And, like its cinematic successor, it ends with a triumph, though a small one, that promises the good guys will fight on. —Kenneth Lowe

- Ran

Year: 1985

Director: Akira Kurosawa

6_Ran.jpg

Kurosawa’s insane popularity in the West has as much to do with his keen understanding of its traditional storytelling as his virtuoso skill and workmanlike insistence on excellence, and Ran showcases both these facets of the director when he was arguably at the height of his influence. Ran retells the story of Shakespeare’s King Lear, with the crucial opening scene featuring the lord divvying up his province amongst three quarrelsome samurai sons rather than three daughters. Devotees of the Bard will recognize the story beats and delight at the Japanese period-piece spin on the classic tale, and history buffs will find that it translates disturbingly well to Japan’s chaotic Age of Civil War. With sweeping operatic performances, hundreds of extras engaged in epic battle with sword, bow and firearm, and some of Kurosawa’s most arresting imagery, it’s essential viewing for any film buff. Like the best tragedy, we know exactly how Lord Ichimonji’s story will end. Kurosawa’s spellbinding direction ensures we nonetheless can’t look away. —Kenneth Lowe

- Heaven and Earth (Ten to Chi to)

Year: 1990

Director: Haruki Kadokawa

7_Heaven_and_Earth.jpg

Based on a ferocious rivalry between two larger-than-life historical samurai, Heaven and Earth is a lavish war movie. Portraying young samurai Kagetora (Takaaki Enoki) as an earnest nobleman seeking to protect his kingdom from the invading warlord Takeda Shingen (Masahiko Tsugawa), the story follows the ups and downs of his leadership. This is a movie in which mighty armies of cavalry clash, and one man’s resolve hardens into bitter ferocity. After the maneuvering, the treachery and the clash of armies, it all builds to exactly the inevitable showdown you hope it does: Two guys in head-to-toe armor with swords slugging it out on horseback in the middle of a shallow river. It’s a period piece about the age of civil war with lots of action, hundreds of extras who needed to spend hours getting into armor and mounting horses, and very few frills. —Kenneth Lowe

- The Master Spearman

Year: 1960

Director: Tomu Uchida

8_The_Master_Spearman.jpg

A samurai’s lord kills himself. Granted a last minute reprieve from joining his lord in death, he elects for a late life of earthly pleasures. He flatly states the chivalric samurai code of bushido is for fools when a family members demands he take his own life and end the embarrassment to his clan. And yet, he’s persuaded to take up his spear again when he’s offered the chance to redeem himself by participating in one of the pivotal battles of the Age of Civil War. It’s difficult to tell if Tomu Uchida is extolling the virtues of the warrior spirit or laying bare the foolishness of samurai pageantry—and it may be up to the viewer to decide. Uchida, a well-known director from Japan’s silent film era in the ’20s and ’30s, remains largely unknown in the West, even though his films are considered foundational to the samurai genre. Uchida was stranded in occupied Manchuria for nearly a decade following the Second World War, a time of his life about which little has been written. His pre-war work barely survives and by all accounts is filled with weird stylistic and political inconsistency. If you can find it, The Master Spearman (originally Sake to onna to yari, “Sake, Woman and Spear” in Japanese) is one of the latter films from a Japanese director whose work informed those who would come after him. —Kenneth Lowe

- Kagemusha

Year: 1980

Director: Akira Kurosawa

4_Kagemusha.jpg

The film’s title means “Shadow Warrior,” a truly badass phrase that roughly translates as a decoy for an important leader. This production, mounted with the aid of funding from George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, almost had as much drama behind the scenes as the sweeping Sengoku Jidai war epic that made it onto the celluloid. Lucas and Coppola stepped in when Toho Studios couldn’t come up with the money to finish the picture, and Shintaro Katsu of Zatoichi fame was originally slated as the star, but reportedly angered Kurosawa by bringing his own camera crew in an attempt to document the director’s work. Tatsuya Nakadai would step into the dual role of historical warlord Takeda Shingen and the lowly criminal, rescued from crucifixion by Shingen’s brother, who looks exactly like him.

Kagemusha is a massive war epic, but it’s also a study of a man having greatness thrust upon him and choosing to find meaning in a life he’s essentially inherited. When Shingen is mortally wounded in the course of his war for supremacy over Japan, he orders that his decoy take his place and his death be kept secret for three years for the good of the clan. Overwhelmed at first, the decoy soon adopts the slain lord’s mannerisms and even fools his most trusted advisers and some family members. It will end tragically, of course. Shingen’s decoy commits entirely to the task of assuming Takeda Shingen’s mantle. That means accepting his fate as well. —Kenneth Lowe

- Legend of the Eight Samurai

Year: 1983

Director: Kinji Fukasaku

9_Legend_of_Eight_Samurai.jpg

This film feels a bit like it was conceived by a child, but at least it was a kid with a very active imagination. A colorful, overlong (133 minutes?!?) would-be supernatural samurai epic, it actually feels a bit more like one of the late ’80s “ninja” films that proliferated in Hong Kong and made their way to American late-night television in short order. The story of a cursed princess who searches for eight mystical warriors/samurai who hold the ability to end her family’s suffering, it happened to reunite Sonny Chiba of The Street Fighter fame with Sue Shiomi, whom he memorably starred alongside in Sister Street Fighter. Legend of the Eight Samurai, on the other hand, is a classic case of overstuffed but fun to look at—gorgeous costumes and moody sets that conjure up elements of gothic horror, with plenty of monsters, magic, historically inaccurate guns, action set-pieces and a plot that is close to incomprehensible regardless of whether you’re watching with subtitles or dubbing. This is a film that should be viewed either late at night with a bunch of whiskey or early in the morning with a bunch of sugar cereal. —