Was This The First Dead Sea Scroll ??

More than a century ago, an antiquities dealer from Jerusalem claimed he had discovered an ancient version of the book of Deuteronomy. But was it a fake?

“Is that what you’re wearing?” the security guard asked as I stood at the entrance to the giant Wadi Mujib gorge in southern Jordan.

I was dressed in what my brother refers to as my ‘journalist costume’: long-sleeve khaki shirt, green army trousers and boots – a fashion-backward ensemble meant to protect me from the pounding summer sun.

“Yes?” I replied tentatively. The guard smirked and waved me through.

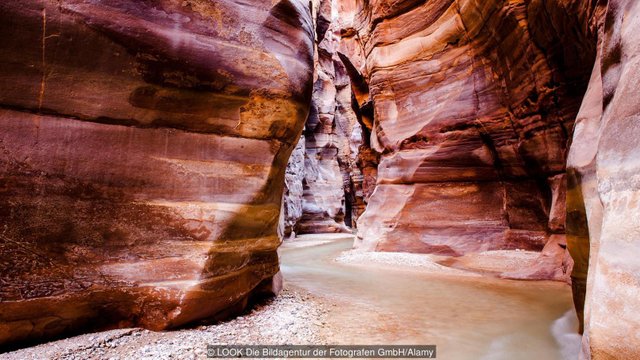

The author began his journey to unravel a century-old mystery in Jordan’s Wadi Mujib

Sheer rust-tinted cliffs climbed more than 30m on either side of me, and a channel of deep green water trickled out toward the Dead Sea. The more I walked, the deeper it became, and soon I was in water up to the collar of my very inappropriate shirt. I looked over at my driver, who had joined me on what was now, clearly, an ill-advised outing. He was luxuriating in his boxer shorts.

“Flood,” he said.

Then he dived under the water.

We hiked this way for the better part of two hours, scaling rocks and dodging waterfalls in the flooded passageway until the current became too rough and we had to turn back.

My visit to Wadi Mujib (believed to be what was known in the Bible as Arnon) was the first step in my journey to solve a century-old mystery.

That story began in 1883, when Moses Wilhelm Shapira, an antiquities dealer from Jerusalem, showed up on the doorstep of London’s British Museum claiming to have in his possession the oldest biblical manuscript in the world, a set of scrolls inscribed with the Book of Deuteronomy, the fifth and final of the Five Books of Moses, which together with Prophets and Writings comprise the Old Testament. He claimed the manuscript had been discovered by nomadic Bedouin tribesmen in a cave overlooking Wadi Mujib. The text, Shapira noted, was remarkably different from that used in churches and synagogues, suggesting that the version believed to have been passed down from God to Moses had, in fact, been altered by human hands.

What’s more, Shapira wanted one million pounds for it – about £186 million in today’s money.

Shapira tried to sell his manuscript to the British Museum for one million pounds

But there were those who doubted Shapira’s bold claim, including noted French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau, who had previously accused Shapira of peddling counterfeit artefacts. Before agreeing to purchase the scrolls, the British Museum hired Christian David Ginsburg, one of the great Bible scholars of the day, to authenticate the ancient manuscript. While Ginsburg toiled away in the museum, Shapira became an overnight celebrity as newspapers reported on his comings and goings in their literary gossip columns.

After four weeks, Ginsburg came out with a verdict: the manuscript was a fake. Shapira, he said, had taken a genuinely old Torah scroll, sliced off its blank lower margin, and inscribed that ancient-looking strip with his own version of Deuteronomy.

Distraught and humiliated, Shapira fled the UK. In March 1884, he gathered what money he had left, took a room in a seedy hotel in Rotterdam, and shot himself in the head.

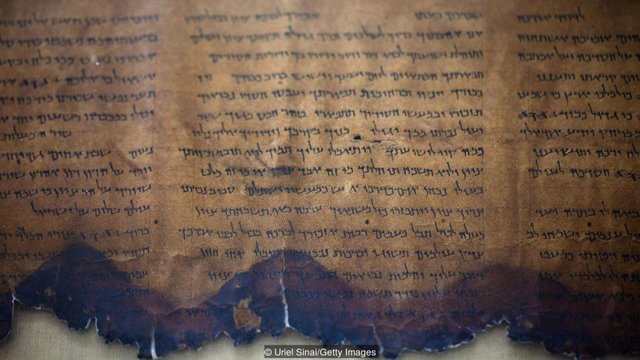

For those following the affair, Shapira’s death at the age of 54 seemed to be the sad end of his story. But fast forward more than 60 years to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, thousands of ancient biblical scrolls and scroll fragments first uncovered in 1947. Shapira’s Deuteronomy was said to have been stashed away in a cave. So, too, were the Dead Sea Scrolls. Shapira’s manuscript was full of interesting departures from the traditional Bible text. So, too, were the Dead Sea Scrolls. Shapira’s text was found by Bedouin wandering the deserts near the Dead Sea. So, too, were the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Discovered more than 60 years later, the Dead Sea Scrolls bore a striking resemblance to Shapira’s manuscript

The similarities were too striking to dismiss. Beginning in the 1950s, a number of scholars decided to return to Shapira’s manuscript, using methods not available to Ginsburg in 1883, to prove once and for all whether it was real or fake.

But there was a problem: Shapira’s scrolls had mysteriously vanished.

My fascination with Shapira’s scrolls – which I had first learned about from my father, a Bible scholar – had proved too strong to resist. Several years ago, keen to begin researching a book I planned to write on the manuscript, I had travelled to Jordan after a week in Israel, where I was supposed to be working on an article about Arab soldiers who serve in Israel’s army.

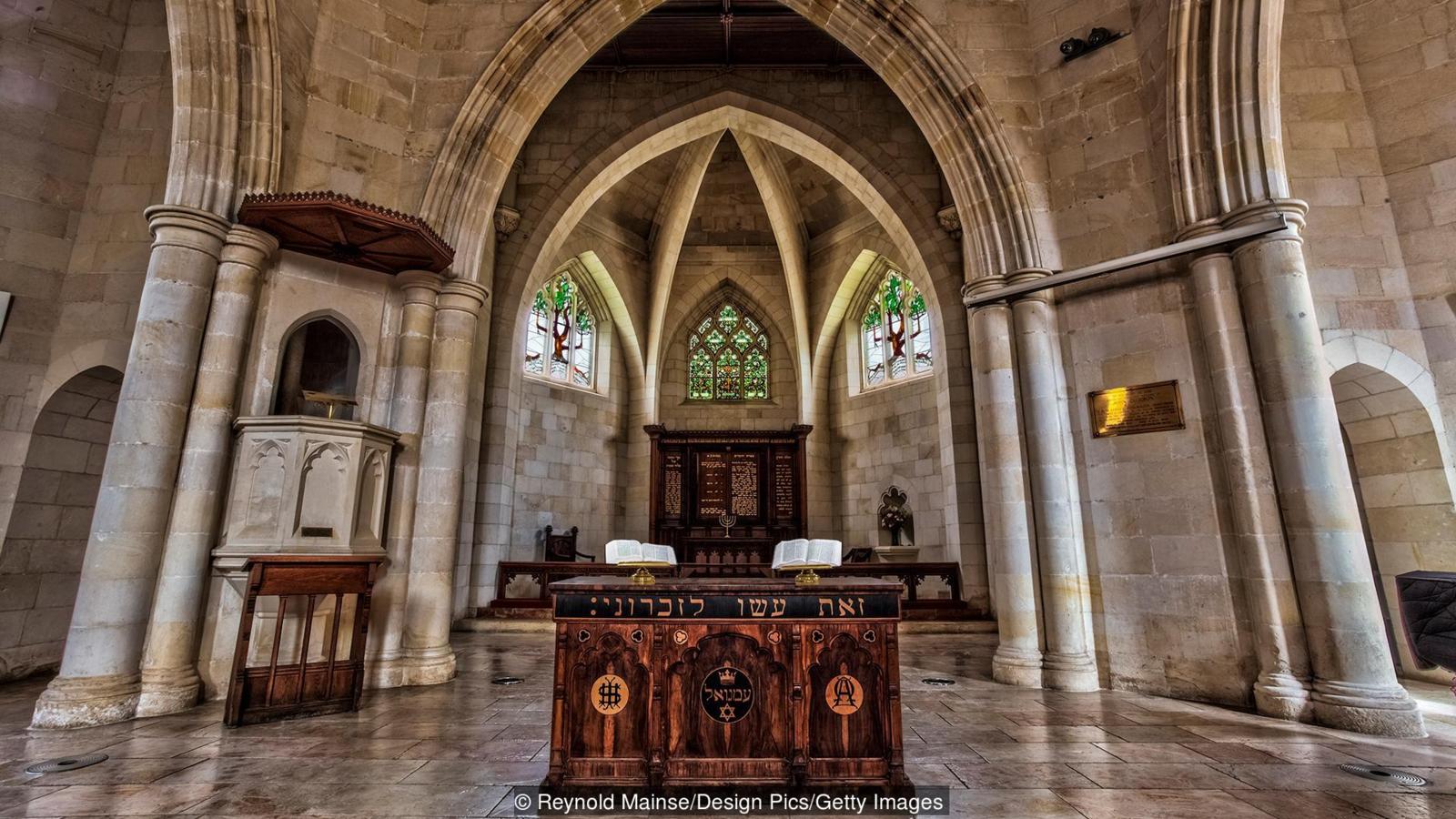

Instead, I spent much of my time in Jerusalem’s Old City on Shapira’s trail. I began at Christ Church, where Shapira was married, baptized his two daughters, and was known to read his Bible during the pastor’s Sunday sermon. From there I walked down the cobblestones of Armenian Quarter Street and hung a right onto King David Street, descending the broad steps to Christian Street, where Shapira once had his antiquities shop. Apart from the T-shirts hanging outside a souvenir stall the street looked much as it would have when Shapira worked there.

Shapira married his wife and baptized his two daughters in Jerusalem’s Christ Church

While my visit allowed me to envision Shapira’s Jerusalem, I uncovered no clues as to the whereabouts of his missing scrolls. This was not surprising – after all, they had disappeared in London.

So I booked a ticket to the UK.

The British Library sits across from London’s King’s Cross/St Pancras Station, but while the train depot was teeming, the library was muted. Researchers sat silently at wooden desks, carefully reading through illuminated manuscripts, antique letters and musical scores. I had come to pore over the dozens of authentic Torah scrolls also purchased from Shapira before that fateful summer of 1883, along with a dossier holding correspondence relating to the Shapira affair.

Although the famous missing manuscript was nowhere to be found among the 150 million items in the library’s astounding collection, I did uncover a handwritten note from the museum’s chief librarian in 1883 noting that after Shapira died, his widow, Rosette, had sent two small fragments of the scrolls to a German scholar. If I could track these fragments down, I realised, I could discover the truth about Shapira’s manuscript.

So I booked a flight to Germany.

The town of Schlitz in central Germany is named for its river, but is better known for the romantic castles that infuse its Old Town with a quaint vibe. Craftsmen at Germany’s oldest distillery produce schnapps and whisky – bottled courage for a winter’s day as cold as the one I chose to visit Annette Schwarz-Scheuls, a distant cousin of Shapira’s late wife.

The author travelled to Schlitz, Germany, to visit a distant cousin of Shapira’s late wife

“I can’t be neutral,” Schwarz-Scheuls told me as we warmed up over coffee and pastries in her kitchen. The 52-year-old woman had already told me she didn’t have the scrolls, so I’d moved on to asking if they’d really been fakes. “I’m on the side of the family. It’s only a personal opinion, a very personal opinion, that he is [a] ‘master forger’. It is not [true] in my eyes. You understand this?”

I did understand. Although I hadn’t found the manuscript fragments, I had also failed to uncover anything that suggested the scrolls were forgeries. Indeed, after more than three years of searching I was becoming increasingly convinced that they had been real. More than a century after his death, Shapira’s family agreed.

But my search was going nowhere. In Jordan and Israel, the UK and Germany, I had hit dead end after dead end.

Source:bbc.com