The evolution of the selfie: how our much-mocked photos have matured

Against all odds, the selfie has evolved from an embarrassing teenage trend into a modern phenomenon. Now, some experts are beginning to see them as a good thing

by Anna Hart

Few 21st-century trends have been as thoroughly maligned as the selfie, the digital self-portrait snapped at arm’s length on a smartphone. But since around 2013, when the word received the seal of approval from Oxford Dictionaries, the debate over what these images reveal about modern life has softened and shifted. It’s no longer smart to condemn them as proof that an entire generation are narcissists. Now experts – including art historians and psychologists – argue that selfies perform important social functions.

“When I see a selfie, I see people trying to make connections in an increasingly impersonal world,” says art historian James Hall, author of The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History. “They are trying to identify themselves, to reinvent themselves, as self-portraitists throughout history have sought to do.”

The selfie too has proved a master of reinvention. The selfie of 2017 looks radically different to the selfie of 2013. In 2017, we’re no longer “sparrowfacing”, the wide-eyed variation on a pouty “duckface”. “Sorority arm”, the flattering update on the old hand-on-hip pose, which nips in the waist with your hand and makes the arm look thinner, is now as old-hat as, well, sororities themselves.

In 2017, the big trend has been the “plandid”, AKA the planned candid selfie, which does away with selfie sticks, selfie drones and, um, arms altogether and recruits a photographer. Does this still constitute a selfie? Thanks to the glaringly obvious self-orchestrated element of plandids, yes; we’re still essentially both the photographer and subject of that particular shot.

When the first phone with a clip-on camera hit shelves back in 2001, technology journalists sneered; the idea that a phone could ever replace a digital camera seemed faintly ridiculous. Today, four out of five Brits own a smartphone – and we are used to upgrading our images as a matter of course.

When the selfie-tweaking app FaceTune first came out it was seen as a Kardashian level of vain, but now with phones such as Google Pixel 2 providing built-in portrait editor tools, the bar for a pro-selfie has been raised forever. We no longer even have to use our fingers, just asking Google Assistant: “Ok Google, take a selfie” is the most modern way of being in charge of your own image. In 2017, it’s now accepted that we’re all the photographic directors of our own lives.

The “planned candid” is a move away from studiously posed pictures and, some would argue, a backlash against the overly posed, pouty selfie of the past. Yes, the irony of this backlash being so meticulously planned is not lost on us. Meanwhile, psychologists are still hotly debating if the fact that most women on dating sites snap their selfies from above tells us that single women subconsciously assume an aspect of submission to potential mates, or whether the explanation is simpler: it’s just a more flattering angle.

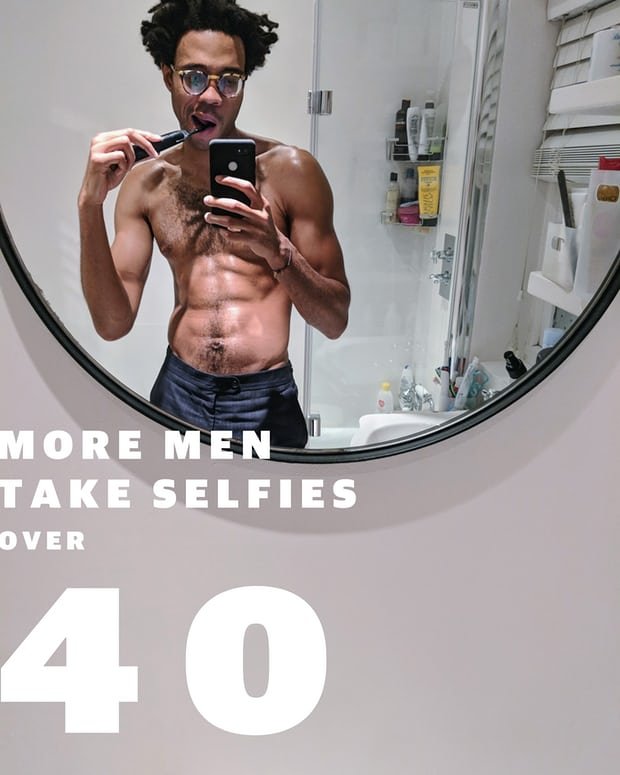

Instead of deriding selfies as a psychologically and socially destructive force, academics now seek to glean valuable insights from this rich sociological databank. Launched by the media theorist Lev Manovich and digital analyst Daniel Goddemeyer, the site selfiecity.net analysed Instagram selfie patterns around the world, finding that the average age of the selfie-taker is 23.7.

.jpg)

As anyone with an Instagram account can attest, the power to (re)brand yourself and curate your own visual journal is in turn intoxicating, addictive, exhilarating and emotionally exhausting. “Selfies are part of modern life,” says psychologist Jessamy Hibberd, author of This Book Will Make You Confident. “It’s how you use them that determines whether they have a positive or negative impact on your wellbeing.” One US study found teens who spend more time than average on screen activities are more likely to be unhappy, which raises the question as to whether selfies are detrimental to self esteem.

But we certainly aren’t passive victims of the selfie age, being swept along by a tide of narcissism; we’re all in control of how we selfie. “The more we recognise selfies as visual journals, the sooner people will realise that they do not represent the decline of civilisation or a narcissistic generation,” says Hibberd. “It’s healthy to mark significant occasions and revel in a success, and selfies help punctuate these moments in our lives. Celebratory selfies, such as toasting a promotion, can combat our natural tendency to play down our successes.”

We also use selfies as a networking tool, a branding device. Reputations were once built on a CV and references, while a privileged few had access to publicists and agents. Today, the image we present to the world is in our hands; as individuals we’re able to control our own image, to curate a selfhood, to build a personal brand.

.jpg)

“One of the critical ways in which the brain constructs the sense of our self is by observing other people’s reactions to us,” says Will Storr, author of Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing To Us. “The famous quote from psychological literature is: ‘We are what we think other people think we are.’ If we think other people think we’re beautiful and special, for example, we’re likely to think that too. So you see how the comments underneath the selfies we post can have potentially powerful effects on our sense of self.”

Advertisement

So perhaps it’s time to ditch the guilt about caring about the number of likes we accumulate, or spending a bit of time editing out red-eye in an otherwise perfect holiday snap. “Even if we’re consciously aware that many of our commenters are sycophantic, fishing for their own reciprocal compliments or, more often, ‘just being nice’, their comments still feel good,” says Storr. “We still feel bad when we don’t get them.”

In fact, being slightly selfie-obsessed is a trait that could once have been advantageous in evolutionary terms. “Being overly concerned about pictures of yourself doesn’t make you a narcissist,” says Dr Kelly McGonigal, a psychologist and the author of The Willpower Instinct. “It’s entirely normal, and from a survival perspective helpful, to be obsessed with gossip about yourself, pictures of yourself or responses to you online. Status anxiety is part and parcel of being in a society.” We are interested in what friends and family are doing, saying, thinking and feeling – particularly if it’s a response to us. This is how we establish our place in society and form supportive relationships with likeminded people.

“Social historians see selfies as part of a long tradition stretching back to self portraits, as a means of exploring ourselves and experimenting with our identity,” says Hall. “All that’s changed is the technology.”