Human vs Computer: Becoming More Employable then an Algorithm

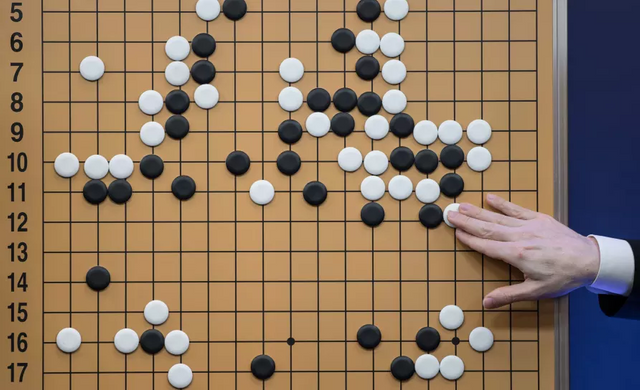

Chinese philosopher, Confucius, praised Go as the only game worth playing. Originating in China at least 2,500 years ago, Go is a simple game of encirclement but one with a strategy deeper than chess, requiring both analytical skill and intuition.

Its subtleties are such that in 1997 a US astrophysicist famously told The New York Times that “it may be a hundred years before a computer beats humans at Go’’. He was wrong. It took just 20 years. In May, Google’s AlphaGo computer beat the world champion 3-0 having humbled a famous grandmaster along the way.

If a Go grandmaster isn’t safe from a machine, is anyone?

FORECASTING THE FUTURE

Computers have quickly moved from providing pure processing power to learning and adapting without programming, creating widespread unease that the rise of the machines will leave many jobless. In 2013, Oxford University research suggested that within the next 10-20 years some 47 per cent of US jobs will be at risk of being replaced by computers and algorithms.

“Computers have moved beyond their previous constraints when they could only be programmed to do codified tasks, and we are now finding examples of computers being able to do work we never thought could be automated, whether it’s writing a news story or diagnosing health conditions,” says Dr Josh Healy, from the Centre for Workplace Leadership at the University of Melbourne.

But Dr Healy says the future of work isn’t as bleak as some of the more alarmist forecasts. It is a more nuanced future in which the unique skills of humans will be even more valued than today. It means the urgent policy problem won’t be job creation, but instead ensuring people are equally equipped to share in this future.

Since the Industrial Revolution 200 years ago, technological advances have always led to job destruction, but more new jobs have always been created. At this stage, there is no clear evidence this will be any different to what has gone before. We aren’t eliminating work, unemployment rates aren’t blowing out, work isn’t disappearing,” says Dr Healy, a labour and workplace relations academic.

[...]

LEARNING LITERACY 4.0

The trends are stark, but Dr Healy says rather than suggesting mass human redundancy, what we are facing is a shift in the type of work people will be doing.

“While these technological developments will touch most of us, the impact on most jobs will be around the edges,” says Dr Healy. “We will start to see portions of jobs being hived off to increasingly capable machines, but that will free up people to focus on non-routine work that machines struggle to do. This is the sort of work that isn’t predictable, where people have to exercise discretion, judgement and creativity in what they do, and where they have to collaborate.”

It is what researchers are calling augmented work.

“People will still need to know the technical aspects of technology and how it works, and they will still have to have diagnostic abilities that come from a grounding in a discipline,’’ says Dr Healy. “But there will be a new value on taking the output of technology and being able to use it to create, for example, a specific client brief, or use it in a courtroom, to design something, or be able to interact with people, be it co-workers, customers or patients.”

But these non-routine skills are all highly dependent on language, especially digital text communications that education researcher Professor Lesley Farrell says is driving the creation of a whole new type of literacy. Just as the new digital technologies are being called the fourth industrial revolution, researchers are calling the new literacies Literacy 4.0.

Source: Pursuit