Muhammad Ali

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Cassius Clay" and "Mohammad Ali" redirect here. For other names, see Cassius Marcellus Clay and Mohammad Ali (disambiguation).

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali NYWTS.jpg

Ali in 1967

Born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.

January 17, 1942

Louisville, Kentucky, U.S.

Died June 3, 2016 (aged 74)

Scottsdale, Arizona, U.S.

Cause of death Septic shock

Resting place Cave Hill Cemetery, Louisville, Kentucky, U.S.

Monuments

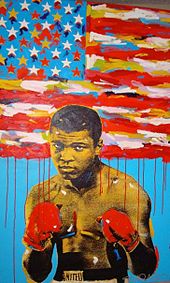

Muhammad Ali Center Muhammad Ali Mural, Los Angeles, CA[1]

Other names

The Greatest

The People's Champion

The Louisville Lip

The King of Boxing

Education Central High School (1958)[2]

Criminal charge Draft evasion[3]

Criminal penalty Five years in prison (not served), fined $10,000 and banned from boxing for three years[3]

Criminal status Conviction overturned[3]

Spouse(s)

Sonji Roi (m. 1964; div. 1966)

Belinda Boyd (m. 1967; div. 1977)

Veronica Porché Ali (m. 1977; div. 1986)

Yolanda Williams (m. 1986)[2]

Children 9, including Laila Ali[2]

Parent(s)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr.

Odessa Grady Clay[2]

Awards

List of awards[show]

Website muhammadali.com

Boxing career

Statistics

Weight(s) Heavyweight

Height 6 ft 3 in (191 cm)[7]

Reach 78 in (198 cm)[7]

Stance Orthodox

Boxing record

Total fights 61

Wins 56

Wins by KO 37

Losses 5

Medal record[hide]

Men's amateur boxing

Representing United States

Olympic Games

Gold medal – first place 1960 Rome Light heavyweight

Muhammad Ali (/ɑːˈliː/;[8] born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.;[9] January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. He is widely regarded as one of the most significant and celebrated sports figures of the 20th century. From early in his career, Ali was known as an inspiring, controversial, and polarizing figure both inside and outside the ring.[10][11]

Cassius Clay was born and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, and began training as an amateur boxer when he was 12 years old. At age 18, he won a gold medal in the light heavyweight division at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome and turned professional later that year. At age 22 in 1964, he won the WBA, WBC, and lineal heavyweight titles from Sonny Liston in a major upset. Clay then converted to Islam and changed his name from Cassius Clay, which he called his "slave name", to Muhammad Ali. He set an example of racial pride for African Americans and resistance to white domination during the Civil Rights Movement.[12][13]

In 1966, two years after winning the heavyweight title, Ali further antagonized the white establishment by refusing to be drafted into the U.S. military, citing his religious beliefs and opposition to American involvement in the Vietnam War.[12][14] He was eventually arrested, found guilty of draft evasion charges, and stripped of his boxing titles. He successfully appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which overturned his conviction in 1971, by which time he had not fought for nearly four years and thereby lost a period of peak performance as an athlete. Ali's actions as a conscientious objector to the war made him an icon for the larger counterculture generation.[15][16]

Ali is regarded as one of the leading heavyweight boxers of the 20th century, and remains the only three-time lineal heavyweight champion. During 1964, Ali reigned as the undisputed heavyweight champion. His record of the most wins in heavyweight title bouts in modern boxing history at 22 was unbeaten for 35 years, 7 months and 11 days until Wladimir Klitschko won his 23rd title bout in 2014. Ali is the only boxer to be named The Ring magazine Fighter of the Year six times. He was also ranked as the greatest athlete of the 20th century by Sports Illustrated, the Sports Personality of the Century by the BBC, and the third greatest athlete of the 20th century by ESPN SportsCentury. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he was involved in several historic boxing matches.[17] Notable among these were the first Liston fight; the "Fight of the Century", "Super Fight II" and the "Thrilla in Manila" against his rival Joe Frazier; and "The Rumble in the Jungle" against George Foreman.

At a time when most fighters let their managers do the talking, Ali thrived in and indeed craved the spotlight, where he was often provocative and outlandish.[18][19][20] He was known for trash talking, and often freestyled with rhyme schemes and spoken word poetry, both for his trash talking in boxing and as political poetry for his activism, anticipating elements of rap and hip hop music.[21][22][23] As a musician, Ali recorded two spoken word albums and a rhythm and blues song, and received two Grammy Award nominations.[23] As an actor, he performed in several films and a Broadway musical. Additionally, Ali wrote two autobiographies, one during and one after his boxing career.

As a Muslim, Ali was initially affiliated with Elijah Muhammad's Nation of Islam (NOI) and advocated their black separatist ideology. He later disavowed the NOI, adhering to Sunni Islam, practicing Sufism, and supporting racial integration, like his former mentor Malcolm X.

After retiring from boxing at age 39 in 1981, Ali devoted his life to religious and charitable work. In 1984, Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome, which his doctors attributed to boxing-related brain injuries.[citation needed] As his condition worsened, Ali made limited public appearances and was cared for by his family until his death on June 3, 2016, in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Contents [hide]

1 Early life and amateur career

2 Professional boxing

2.1 Early career

2.2 Heavyweight champion

2.3 Exile and comeback

2.3.1 Fantasy fight against Rocky Marciano

2.3.2 Legal vindication

2.3.3 First fight against Joe Frazier

2.3.4 Fights against Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry Quarry, Floyd Patterson, Bob Foster, and Ken Norton

2.3.5 Second fight against Joe Frazier

2.4 Heavyweight champion (second reign)

2.5 Later career

3 Personal life

3.1 Marriages and children

3.2 Religion and beliefs

3.2.1 Affiliation with the Nation of Islam

3.2.2 Later beliefs

4 Vietnam War and resistance to the draft

4.1 Impact of Ali's draft refusal

4.2 NSA and FBI monitoring of Ali's communications

5 Later years

5.1 Illness and death

5.2 Tributes

5.3 Memorial

6 Boxing style

6.1 Trash-talk

7 Ali and his contemporaries

7.1 Ali and Frazier

7.1.1 Friendship

7.1.2 Opponents

7.1.3 Trash talk and altercations

7.1.4 Finale

8 Legacy

8.1 Ranking in boxing history

8.2 Spoken word poetry and music

8.3 In the media and popular culture

9 Professional boxing record

10 See also

11 Notes

12 References

13 Further reading

14 External links

Early life and amateur career

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. (/ˈkæʃəs/) was born on January 17, 1942, in Louisville, Kentucky.[24] He had a sister and four brothers.[25][26] He was named for his father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr. (1912–1990), who himself was named in honor of the 19th-century Republican politician and staunch abolitionist, Cassius Marcellus Clay, also from the state of Kentucky. Clay's father's paternal grandparents were John Clay and Sallie Anne Clay; Clay's sister Eva claimed that Sallie was a native of Madagascar.[27] He was a descendant of slaves of the antebellum South, and was predominantly of African descent, with smaller amounts of Irish[28] and English heritage.[29][30] His father painted billboards and signs,[24] and his mother, Odessa O'Grady Clay (1917–1994), was a domestic helper. Although Cassius Sr. was a Methodist, he allowed Odessa to bring up both Cassius Jr. and his younger brother Rudolph "Rudy" Clay (later renamed Rahman Ali) as Baptists.[31] Cassius Jr. attended Central High School in Louisville.[2]

Clay grew up amid racial segregation. His mother recalled one occasion when he was denied a drink of water at a store—"They wouldn't give him one because of his color. That really affected him."[12] He was also affected by the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, which led to young Clay and a friend's taking out their frustration by vandalizing a local railyard.[32][33]

Cassius Clay (second from right and later Ali) at the 1960 Olympics

Clay was first directed toward boxing by Louisville police officer and boxing coach Joe E. Martin,[34] who encountered the 12-year-old fuming over a thief's having taken his bicycle. He told the officer he was going to "whup" the thief. The officer told Clay he had better learn how to box first.[35] Initially, Clay did not take up on Martin's offer, but after seeing amateur boxers on a local television boxing program called Tomorrow's Champions, Clay was interested in the prospects of fighting for fame, fortune, and glory.[citation needed] For the last four years of Clay's amateur career he was trained by boxing cutman Chuck Bodak.[36]

Clay made his amateur boxing debut in 1954 against local amateur boxer Ronnie O'Keefe. He won by split decision.[37] He went on to win six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles, two national Golden Gloves titles, an Amateur Athletic Union national title, and the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[38] Clay's amateur record was 100 wins with five losses. Ali said in his 1975 autobiography that shortly after his return from the Rome Olympics, he threw his gold medal into the Ohio River after he and a friend were refused service at a "whites-only" restaurant and fought with a white gang. The story was later disputed, and several of Ali's friends, including Bundini Brown and photographer Howard Bingham, denied it. Brown told Sports Illustrated writer Mark Kram, "Honkies sure bought into that one!" Thomas Hauser's biography of Ali stated that Ali was refused service at the diner but that he lost his medal a year after he won it.[39] Ali received a replacement medal at a basketball intermission during the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, where he lit the torch to start the games.

Professional boxing

Early career

On-site poster for Cassius Clay's fifth professional bout

Clay made his professional debut on October 29, 1960, winning a six-round decision over Tunney Hunsaker. From then until the end of 1963, Clay amassed a record of 19–0 with 15 wins by knockout. He defeated boxers that included Tony Esperti, Jim Robinson, Donnie Fleeman, Alonzo Johnson, George Logan, Willi Besmanoff, LaMar Clark, Doug Jones and Henry Cooper. Clay also beat his former trainer and veteran boxer Archie Moore in a 1962 match.[40][41]

These early fights were not without trials. Clay was knocked down both by Sonny Banks and Cooper. In the Cooper fight, Clay was floored by a left hook at the end of round four and was saved by the bell, going on to win in the predicted 5th round due to Cooper's severely cut eye. The fight with Doug Jones on March 13, 1963 was Clay's toughest fight during this stretch. The number-two and -three heavyweight contenders respectively, Clay and Jones fought on Jones' home turf at New York's Madison Square Garden. Jones staggered Clay in the first round, and the unanimous decision for Clay was greeted by boos and a rain of debris thrown into the ring (watching on closed-circuit TV, heavyweight champ Sonny Liston quipped that if he fought Clay he might get locked up for murder). The fight was later named "Fight of the Year" by The Ring magazine.[42]

In each of these fights, Clay vocally belittled his opponents and vaunted his abilities. He called Jones "an ugly little man" and Cooper a "bum". He was embarrassed to get in the ring with Alex Miteff. Madison Square Garden was "too small for me".[43] Clay's behavior provoked the ire of many boxing fans.[44] His provocative and outlandish behavior in the ring was inspired by professional wrestler "Gorgeous George" Wagner.[45] Ali stated in a 1969 interview with the Associated Press' Hubert Mizel that he met with Gorgeous George in Las Vegas in 1961 and that the wrestler inspired him to use wrestling jargon when he did interviews.[46]

After Clay left Moore's camp in 1960, partially due to Clay's refusing to do chores such as dish-washing and sweeping, he hired Angelo Dundee, whom he had met in February 1957 during Ali's amateur career,[47] to be his trainer. Around this time, Clay sought longtime idol Sugar Ray Robinson to be his manager, but was rebuffed.[48]

Heavyweight champion

See also: Muhammad Ali vs. Sonny Liston

By late 1963, Clay had become the top contender for Sonny Liston's title. The fight was set for February 25, 1964, in Miami Beach. Liston was an intimidating personality, a dominating fighter with a criminal past and ties to the mob. Based on Clay's uninspired performance against Jones and Cooper in his previous two fights, and Liston's destruction of former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson in two first-round knock outs, Clay was a 7–1 underdog. Despite this, Clay taunted Liston during the pre-fight buildup, dubbing him "the big ugly bear". "Liston even smells like a bear", Clay said. "After I beat him I'm going to donate him to the zoo."[49] Clay turned the pre-fight weigh-in into a circus, shouting at Liston that "someone is going to die at ringside tonight". Clay's pulse rate was measured at 120, more than double his normal 54.[50] Many of those in attendance thought Clay's behavior stemmed from fear, and some commentators wondered if he would show up for the bout.

The outcome of the fight was a major upset. At the opening bell, Liston rushed at Clay, seemingly angry and looking for a quick knockout, but Clay's superior speed and mobility enabled him to elude Liston, making the champion miss and look awkward. At the end of the first round, Clay opened up his attack and hit Liston repeatedly with jabs. Liston fought better in round two, but at the beginning of the third round Clay hit Liston with a combination that buckled his knees and opened a cut under his left eye. This was the first time Liston had ever been cut. At the end of round four, Clay was returning to his corner when he began experiencing blinding pain in his eyes and asked his trainer Angelo Dundee to cut off his gloves. Dundee refused. It has been speculated that the problem was due to ointment used to seal Liston's cuts, perhaps deliberately applied by his corner to his gloves.[50] Though unconfirmed, Bert Sugar claimed that two of Liston's opponents also complained about their eyes "burning".[51][52]

Despite Liston's attempts to knock out a blinded Clay, Clay was able to survive the fifth round until sweat and tears rinsed the irritation from his eyes. In the sixth, Clay dominated, hitting Liston repeatedly. Liston did not answer the bell for the seventh round, and Clay was declared the winner by TKO. Liston stated that the reason he quit was an injured shoulder. Following the win, a triumphant Clay rushed to the edge of the ring and, pointing to the ringside press, shouted: "Eat your words!" He added, "I am the greatest! I shook up the world. I'm the prettiest thing that ever lived."[53]

In winning this fight, Clay became at age 22 the youngest boxer to take the title from a reigning heavyweight champion, though Floyd Patterson was the youngest to win the heavyweight championship at 21, during an elimination bout following Rocky Marciano's retirement. Mike Tyson broke both records in 1986 when he defeated Trevor Berbick to win the heavyweight title at age 20.

Soon after the Liston fight, Clay changed his name to Cassius X, and then later to Muhammad Ali upon converting to Islam and affiliating with the Nation of Islam. Ali then faced a rematch with Liston scheduled for May 1965 in Lewiston, Maine. It had been scheduled for Boston the previous November, but was postponed for six months due to Ali's emergency surgery for a hernia three days before.[54] The fight was controversial. Midway through the first round, Liston was knocked down by a difficult-to-see blow the press dubbed a "phantom punch". Ali refused to retreat to a neutral corner, and referee Jersey Joe Walcott did not begin the count. Liston rose after he had been down about 20 seconds, and the fight momentarily continued. But a few seconds later Walcott stopped the match, declaring Ali the winner by knockout. The entire fight lasted less than two minutes.[55]

It has since been speculated that Liston purposely dropped to the ground. Proposed motivations include threats on his life from the Nation of Islam, that he had bet against himself and that he "took a dive" to pay off debts. Slow-motion replays show that Liston was jarred by a chopping right from Ali, although it is unclear whether the blow was a genuine knockout punch.[56]

Ali defended his title against former heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson on November 22, 1965. Before the match, Ali mocked Patterson, who was widely known to call him by his former name Cassius Clay, as an "Uncle Tom", calling him "The Rabbit". Although Ali clearly had the better of Patterson, who appeared injured during the fight, the match lasted 12 rounds before being called on a technical knockout. Patterson later said he had strained his sacroiliac. Ali was criticized in the sports media for appearing to have toyed with Patterson during the fight.[57]

Ali in 1966

Ali and then-WBA heavyweight champion boxer Ernie Terrell had agreed to meet for a bout in Chicago on March 29, 1966 (the WBA, one of two boxing associations, had stripped Ali of his title following his joining the Nation of Islam). But in February Ali was reclassified by the Louisville draft board as 1-A from 1-Y, and he indicated that he would refuse to serve, commenting to the press, "I ain't got nothing against no Viet Cong; no Viet Cong never called me nigger."[58] Amidst the media and public outcry over Ali's stance, the Illinois Athletic Commission refused to sanction the fight, citing technicalities.[59]

Instead, Ali traveled to Canada and Europe and won championship bouts against George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London and Karl Mildenberger.

Ali returned to the United States to fight Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on November 14, 1966. The bout drew a record-breaking indoor crowd of 35,460 people. Williams had once been considered among the hardest punchers in the heavyweight division, but in 1964 he had been shot at point-blank range by a Texas policeman, resulting in the loss of one kidney and 10 feet (3.0 m) of his small intestine. Ali dominated Williams, winning a third-round technical knockout in what some consider the finest performance of his career.

Ali fought Terrell in Houston on February 6, 1967. Terrell was billed as Ali's toughest opponent since Liston—unbeaten in five years and having defeated many of the boxers Ali had faced. Terrell was big, strong and had a three-inch reach advantage over Ali. During the lead up to the bout, Terrell repeatedly called Ali "Clay", much to Ali's annoyance (Ali called Cassius Clay his "slave name"). The two almost came to blows over the name issue in a pre-fight interview with Howard Cosell. Ali seemed intent on humiliating Terrell. "I want to torture him", he said. "A clean knockout is too good for him."[60] The fight was close until the seventh round when Ali bloodied Terrell and almost knocked him out. In the eighth round, Ali taunted Terrell, hitting him with jabs and shouting between punches, "What's my name, Uncle Tom... what's my name?" Ali won a unanimous 15-round decision. Terrell claimed that early in the fight Ali deliberately thumbed him in the eye—forcing Terrell to fight half-blind—and then, in a clinch, rubbed the wounded eye against the ropes. Because of Ali's apparent intent to prolong the fight to inflict maximum punishment, critics described the bout as "one of the ugliest boxing fights". Tex Maule later wrote: "It was a wonderful demonstration of boxing skill and a barbarous display of cruelty." Ali denied the accusations of cruelty but, for Ali's critics, the fight provided more evidence of his arrogance.

After Ali's title defense against Zora Folley on March 22, he was stripped of his title due to his refusal to be drafted to army service.[24] His boxing license was also suspended by the state of New York. He was convicted of draft evasion on June 20 and sentenced to five years in prison and a $10,000 fine. He paid a bond and remained free while the verdict was being appealed.

Exile and comeback

In March 1966, Ali refused to be inducted into the armed forces. He was systematically denied a boxing license in every state and stripped of his passport. As a result, he did not fight from March 1967 to October 1970—from ages 25 to almost 29—as his case worked its way through the appeals process before his conviction was overturned in 1971. During this time of inactivity, as opposition to the Vietnam War began to grow and Ali's stance gained sympathy, he spoke at colleges across the nation, criticizing the Vietnam War and advocating African American pride and racial justice.

Fantasy fight against Rocky Marciano

Main article: The Super Fight

While banned from sanctioned bouts, Ali settled a $1 million lawsuit against radio producer Murray Woroner by accepting $10,000 to appear in a privately staged fantasy fight against retired champion Rocky Marciano.[61] In 1969 the boxers were filmed sparring for about 75 one-minute rounds; they acted out several different endings.[62] A computer program purportedly determined the winner, based on data about the fighters. Edited versions of the bout were shown in movie theaters in 1970. In the U.S. version Ali lost in a simulated 13th-round knockout, but in the European version Marciano lost due to cuts, also simulated.[63] Ali jokingly suggested that prejudice actually determined his defeat in the U.S. version. He was reported to say, "That computer was made in Alabama."[61]

Legal vindication

On August 11, 1970, with his case still in appeal, Ali was granted a license to box by the City of Atlanta Athletic Commission, thanks to State Senator Leroy R. Johnson.[64] Ali's first return bout was against Jerry Quarry on October 26, resulting in a win after three rounds after Quarry was cut.

A month earlier, a victory in federal court forced the New York State Boxing Commission to reinstate Ali's license.[65] He fought Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden in December, an uninspired performance that ended in a dramatic technical knockout of Bonavena in the 15th round. The win left Ali as a top contender against heavyweight champion Joe Frazier.

First fight against Joe Frazier

Main article: Fight of the Century

Ali and Frazier's first fight, held at the Garden on March 8, 1971, was nicknamed the "Fight of the Century", due to the tremendous excitement surrounding a bout between two undefeated fighters, each with a legitimate claim as heavyweight champions. Veteran boxing writer John Condon called it "the greatest event I've ever worked on in my life". The bout was broadcast to 35 foreign countries; promoters granted 760 press passes.[39]

Adding to the atmosphere were the considerable pre-fight theatrics and name calling. Ali portrayed Frazier as a "dumb tool of the white establishment". "Frazier is too ugly to be champ", Ali said. "Frazier is too dumb to be champ." Ali also frequently called Frazier an "Uncle Tom". Dave Wolf, who worked in Frazier's camp, recalled that, "Ali was saying 'the only people rooting for Joe Frazier are white people in suits, Alabama sheriffs, and members of the Ku Klux Klan. I'm fighting for the little man in the ghetto.' Joe was sitting there, smashing his fist into the palm of his hand, saying, 'What the fuck does he know about the ghetto?'"[39]

Ali began training at a farm near Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1971 and, finding the country setting to his liking, sought to develop a real training camp in the countryside. He found a five-acre site on a Pennsylvania country road in the village of Deer Lake, Pennsylvania. On this site, Ali carved out what was to become his training camp, the camp where he lived and trained for all the many fights he had from 1972 on to the end of his career in the 1980s.

The Monday night fight lived up to its billing. In a preview of their two other fights, a crouching, bobbing and weaving Frazier constantly pressured Ali, getting hit regularly by Ali jabs and combinations, but relentlessly attacking and scoring repeatedly, especially to Ali's body. The fight was even in the early rounds, but Ali was taking more punishment than ever in his career. On several occasions in the early rounds he played to the crowd and shook his head "no" after he was hit. In the later rounds—in what was the first appearance of the "rope-a-dope strategy"—Ali leaned against the ropes and absorbed punishment from Frazier, hoping to tire him. In the 11th round, Frazier connected with a left hook that wobbled Ali, but because it appeared that Ali might be clowning as he staggered backwards across the ring, Frazier hesitated to press his advantage, fearing an Ali counter-attack. In the final round, Frazier knocked Ali down with a vicious left hook, which referee Arthur Mercante said was as hard as a man can be hit. Ali was back on his feet in three seconds.[39] Nevertheless, Ali lost by unanimous decision, his first professional defeat.

Fights against Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry Quarry, Floyd Patterson, Bob Foster, and Ken Norton

In 1971, basketball star Wilt Chamberlain challenged Ali to a fight, and a bout was scheduled for July 26. Although the seven foot two inch tall Chamberlain had formidable physical advantages over Ali—weighing 60 pounds more and able to reach 14 inches further—Ali was able to intimidate Chamberlain into calling off the bout by taunting him with calls of "Timber!" and "The tree will fall" during a shared interview. These statements of confidence unsettled his taller opponent to the point that he called off the bout.[66]

After the loss to Frazier, Ali fought Jerry Quarry, had a second bout with Floyd Patterson and faced Bob Foster in 1972, winning a total of six fights that year. In 1973, Ken Norton broke Ali's jaw while giving him the second loss of his career. After initially considering retirement, Ali won a controversial decision against Norton in their second bout. This led to a rematch with Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden on January 28, 1974; Frazier had recently lost his title to George Foreman.

Second fight against Joe Frazier

Main article: Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier II

Ali was strong in the early rounds of the fight, and staggered Frazier in the second round. Referee Tony Perez mistakenly thought he heard the bell ending the round and stepped between the two fighters as Ali was pressing his attack, giving Frazier time to recover. However, Frazier came on in the middle rounds, snapping Ali's head in round seven and driving him to the ropes at the end of round eight. The last four rounds saw round-to-round shifts in momentum between the two fighters. Throughout most of the bout, however, Ali was able to circle away from Frazier's dangerous left hook and to tie Frazier up when he was cornered, the latter a tactic that Frazier's camp complained of bitterly. Judges awarded Ali a unanimous decision.

Heavyweight champion (second reign)

Main articles: The Rumble in the Jungle and Thrilla in Manila

The defeat of Frazier set the stage for a title fight against heavyweight champion George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, on October 30, 1974—a bout nicknamed "The Rumble in the Jungle". Foreman was considered one of the hardest punchers in heavyweight history. In assessing the fight, analysts pointed out that Joe Frazier and Ken Norton—who had given Ali four tough battles and won two of them—had been both devastated by Foreman in second-round knockouts. Ali was 32 years old, and had clearly lost speed and reflexes since his twenties. Contrary to his later persona, Foreman was at the time a brooding and intimidating presence. Almost no onethis man is real is hero so do not understimit associated with the sport, not even Ali's long-time supporter Howard Cosell, gave the former champion a chance of winning.

Ali in 1974

As usual, Ali was confident and colorful before the fight. He told interviewer David Frost, "If you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait 'til I whup Foreman's behind!"[67] He told the press, "I've done something new for this fight. I done wrestled with an alligator, I done tussled with a whale; handcuffed lightning, thrown thunder in jail; only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone

good

thanks

Just look at the picture, it develops is really entertaining ==>

yeap

right u r

beautiful post

thanks

good post

thanks