Breast Cancer: Treatment Options !! JUST CURE IT AND SAVE LIFE.

Breast Cancer: Treatment Options

This section tells you the treatments that are the standard of care for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer. “Standard of care” means the best treatments known. When making treatment plan decisions, patients are encouraged to consider clinical trials as an option. A clinical trial is a research study that tests a new approach to treatment. Doctors want to learn whether the new treatment is safe, effective, and possibly better than the standard treatment. Clinical trials can test a new drug and how often it should be given, a new combination of standard treatments, or new doses of standard drugs or other treatments.

Your doctor can help you consider all your treatment options. To learn more about clinical trials, see the About Clinical Trials and Latest Research sections.

Treatment overview

In cancer care, doctors specializing in different areas of cancer treatment—such as surgery, radiation oncology, and medical oncology—work together to create a patient’s overall treatment plan that combines different types of treatments. This is called a multidisciplinary team. Cancer care teams include a variety of other health care professionals, such as physician assistants, oncology nurses, social workers, pharmacists, counselors, nutritionists, and others. For people older than 65, a geriatric oncologist or geriatrician may also be involved in care. Ask the doctor in charge of your treatment which health care professionals will be part of your treatment team and what they do. This can change over time as your health care needs change.

A treatment plan is a summary of your cancer and the planned cancer treatment. It is meant to give basic information about your medical history to any doctors who will care for you during your lifetime. Before treatment begins, ask your doctor for a copy of your treatment plan. You can also provide your doctor with a copy of the ASCO Treatment Plan form to fill out.

The biology and behavior of breast cancer affects the treatment plan. Some tumors are smaller but grow fast, while others are larger and grow slowly. Treatment options and recommendations are very personalized and depend on several factors, including:

The tumor’s subtype, including hormone receptor status (ER, PR) and HER2 status (see Introduction)

The stage of the tumor

Genomic markers, such as Oncotype DX™ (if appropriate) (See Diagnosis)

The patient’s age, general health, menopausal status, and preferences

The presence of known mutations in inherited breast cancer genes, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2

Even though the breast cancer care team will specifically tailor the treatment for each patient and the breast cancer, there are some general steps for treating early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer.

For both DCIS and early-stage invasive breast cancer, doctors generally recommend surgery to remove the tumor. To make sure that the entire tumor is removed, the surgeon will also remove a small area of healthy tissue around the tumor. Although the goal of surgery is to remove all of the visible cancer, microscopic cells can be left behind, either in the breast or elsewhere. In some situations, this means that another surgery could be needed to remove remaining cancer cells.

For larger cancers, or those that are growing more quickly, doctors may recommend systemic treatment with chemotherapy or hormonal therapy before surgery, called neoadjuvant therapy. There may be several benefits to having other treatments before surgery:

Women who may have needed a mastectomy could have breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) if the tumor shrinks before surgery.

Surgery may be easier to perform.

Your doctor may find out if certain treatments work well for the cancer.

Women may also be able to try a new treatment through a clinical trial.

After surgery, the next step in managing early-stage breast cancer is to lower the risk of recurrence and to get rid of any remaining cancer cells. These cancer cells are undetectable but are believed to be responsible for recurrences of cancer as they can grow over time. Treatment given after surgery is called adjuvant therapy. Adjuvant therapies may include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and/or hormonal therapy (see below for more information on each of these treatments).

Whether adjuvant therapy is needed depends on the chance that any cancer cells remain in the breast or the body and the chance that a specific treatment will work to treat the cancer. Although adjuvant therapy lowers the risk of recurrence, it does not completely get rid of the risk.

Along with staging, other tools can help estimate prognosis and help you and your doctor make decisions about adjuvant therapy. This includes tests that can predict the risk of recurrence by testing your tumor tissue (such as Oncotype Dx™; see Diagnosis). Such tests may also help your doctor better understand the risks from the cancer and whether chemotherapy will help reduce those risks.

When surgery to remove the cancer is not possible, it is called inoperable. The doctor will then recommend treating the cancer in other ways. Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, and/or hormonal therapy may be given to shrink the cancer.

For recurrent cancer, treatment options depend on how the cancer was first treated and the characteristics of the cancer mentioned above, such as ER, PR, and HER2.

Descriptions of the most common treatment options for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer are listed below. Your care plan should also include treatment for symptoms and side effects, an important part of cancer care. Take time to learn about all of your treatment options and be sure to ask questions about things that are unclear. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each treatment and what you can expect while receiving the treatment. It is also important to check with your health insurance company before any treatment begins to make sure it is covered.

People older than 65 may benefit from having a geriatric assessment before planning treatment. Find out what a geriatric assessment involves.

Learn more about making treatment decisions.

Surgery

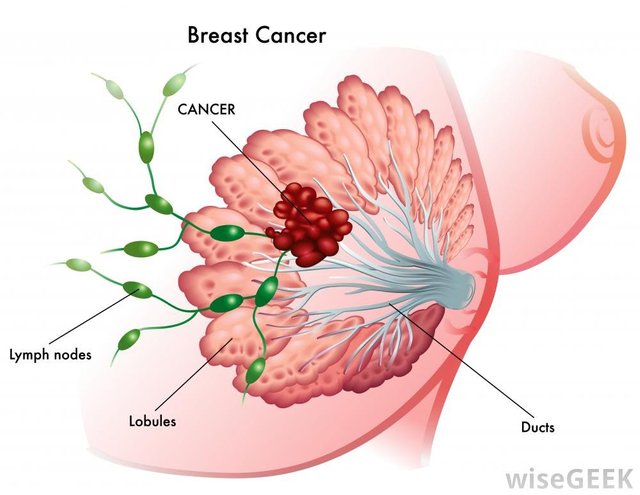

Surgery is the removal of the tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue during an operation. Surgery is also used to examine the nearby axillary lymph nodes, which are under the arm. A surgical oncologist is a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with surgery. Learn more about the basics of cancer surgery.

Generally, the smaller the tumor, the more surgical options a patient has. The types of surgery include the following:

Lumpectomy. This is the removal of the tumor and a small, cancer-free margin of healthy tissue around the tumor. Most of the breast remains. For invasive cancer, radiation therapy to the remaining breast tissue is generally recommended after surgery. For DCIS, radiation therapy after surgery may be an option depending on the patient and the tumor. A lumpectomy may also be called breast-conserving surgery, a partial mastectomy, quadrantectomy, or a segmental mastectomy.

Mastectomy. This is the surgical removal of the entire breast. There are several types of mastectomies. Talk with your doctor about whether the skin can be preserved, called a skin-sparing mastectomy, or the nipple, called a total skin-sparing mastectomy.

Lymph node removal and analysis

Cancer cells can be found in the axillary lymph nodes in some cancers. It is important to find out whether any of the lymph nodes near the breast contain cancer. This information is used to determine treatment and prognosis.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy. In a sentinel lymph node biopsy, the surgeon finds and removes a small number of lymph nodes from under the arm that receive lymph drainage from the breast. This procedure helps avoid removing multiple lymph nodes in an axillary lymph node dissection (see below) procedure for patients whose sentinel lymph nodes are mostly free of cancer. The smaller lymph node procedure helps lower the risk of several possible side effects. Those side effects include swelling of the arm called lymphedema, the risk of numbness, as well as arm movement and range-of-motion problems, which are long-lasting issues that can severely affect a person’s quality of life.

The pathologist then examines these lymph nodes for cancer cells. To find the sentinel lymph node, the surgeon usually injects a dye and/or a radioactive tracer behind or around the nipple. The injection, which can cause some discomfort, lasts about 15 seconds. The dye or tracer travels to the lymph nodes, arriving at the sentinel node first. The surgeon can find the node when it turns color if the dye is used or gives off radiation if the tracer is used.

If the sentinel lymph node is cancer-free, research has shown that it is likely that the remaining lymph nodes will also be free of cancer. This means that no more lymph nodes need to be removed. If only 1 or 2 sentinel lymph nodes have cancer and you plan to have a lumpectomy and radiation therapy to the entire breast, an axillary lymph node dissection may not be not needed. Find out more about ASCO's recommendations for sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Axillary lymph node dissection. In an axillary lymph node dissection, the surgeon removes many lymph nodes from under the arm. These are then examined by a pathologist for cancer cells. The actual number of lymph nodes removed varies from person to person. An axillary lymph node dissection may not be needed for all women with early-stage breast cancer with small amounts of cancer in the sentinel lymph nodes. Women having a lumpectomy and radiation therapy who have a smaller tumor and no more than 2 sentinel lymph nodes with cancer may avoid a full axillary lymph node dissection. This helps reduce the risk of side effects and does not decrease survival. If cancer is found in the sentinel lymph node, whether more surgery is needed to remove more lymph nodes depends on the specific situation.

Most patients with invasive cancer will have either a sentinel lymph node biopsy or an axillary lymph node dissection. However, this may be optional for some patients older than 65. This depends on how large the lymph nodes are, the tumor’s stage, and the person’s overall health.

A sentinel lymph node biopsy alone may not be done if there is obvious evidence of cancer in the lymph nodes before any surgery. In this situation, a full axillary lymph node dissection is preferred. Normally, the lymph nodes are not evaluated for DCIS, since the risk of spread is very low. However, the surgeon may consider a sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients diagnosed with DCIS who choose to have or need a mastectomy. If some invasive cancer is found with DCIS during the mastectomy, which happens occasionally, the lymph nodes will then need to be evaluated. Once the breast tissue has been removed with a mastectomy, it is more difficult to find the sentinel lymph nodes since it is not as obvious where to inject the dye.

Reconstructive (plastic) surgery

Women who have a mastectomy may want to consider breast reconstruction. This is surgery to re-create a breast using either tissue taken from another part of the body or synthetic implants. Reconstruction is usually performed by a plastic surgeon. A woman may be able to have reconstruction at the same time as the mastectomy, called immediate reconstruction. She may also have it at some point in the future, called delayed reconstruction.

Reconstruction may be done at the same time as a lumpectomy to improve the look of the breast and to match the breasts. This is called oncoplastic surgery. Many breast surgeons can do this without the help of a plastic surgeon. Surgery on the healthy breast may also be suggested so both breasts have a similar appearance.

The techniques discussed below are typically used to shape a new breast.

Implants. A breast implant uses saline-filled or silicone gel-filled forms to reshape the breast. The outside of a saline-filled implant is made up of silicone, and it is filled with sterile saline, which is salt water. Silicone gel-filled implants are filled with silicone instead of saline. They were thought to cause connective tissue disorders, but clear evidence of this has not been found. Before having permanent implants, a woman may temporarily have a tissue expander placed that will create the correct sized pocket for the implant. Talk with your doctor about the benefits and risks of silicone versus saline implants. The lifespan of an implant depends on the woman. However, some women never need to have them replaced. Other important factors to consider when choosing implants include:

Saline implants sometimes "ripple" at the top or shift with time, but many women do not find it bothersome enough to replace.

Saline implants tend to feel different than silicone implants. They are often firmer to the touch than silicone implants.

There can be problems with breast implants. The implants can rupture or break, cause pain and scar tissue around the implant, or get infected. Some women may also have problems with the shape or appearance. Although these problems are very unusual, talk with your doctor about the risks.

Tissue flap procedures. These techniques use muscle and tissue from elsewhere in the body to reshape the breast. Tissue flap surgery may be done with a “pedicle flap,” which means tissue from the back or belly is moved to the chest without cutting the blood vessels. A “free flap” means the blood vessels are cut and the surgeon needs to attach the moved tissue to new blood vessels in the chest. There are several flap procedures:

Transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) flap. This method, which can be done as a pedicle flap or free flap, uses muscle and tissue from the lower stomach wall.

Latissimus dorsi flap. This pedicle flap method uses muscle and tissue from the upper back.

Deep inferior epigastric artery perforator (DIEP) flap. The DIEP free flap takes tissue from the abdomen and the surgeon attaches the blood vessels to the chest wall.

Gluteal free flap. The gluteal free flap uses tissue and muscle from the buttocks to create the breast, and the surgeon also attaches the blood vessels.

Because blood vessels are involved with flap procedures, these strategies are usually not recommended for a woman with a history of diabetes or connective tissue or vascular disease, or for a woman who smokes, as the risk of problems during and after surgery is much higher.

The DIEP and gluteal free flap procedures are longer procedures and the recovery time is longer. However, the appearance of the breast may be preferred, especially when radiation therapy is part of the treatment plan.

Talk with your doctor for more information about reconstruction options. When considering a plastic surgeon, choose a doctor who has experience with a variety of reconstructive surgeries, including implants and flap procedures, and can discuss the pros and cons of each procedure.

External breast forms (prostheses)

An external breast prosthesis or artificial breast form provides an option for women who plan to delay or not have reconstructive surgery. These can be made of silicone or soft material, and fit into a mastectomy bra. Breast prostheses can be made to provide a good fit and natural appearance for each woman.

Summary of surgical options

To summarize, surgical treatment options include the following:

Removal of cancer in the breast: Lumpectomy or partial mastectomy, generally followed by radiation therapy if the cancer is invasive. Radiation therapy may or may not be used if it is DCIS. A mastectomy may also be recommended, with or without immediate reconstruction.

Lymph node evaluation: Sentinel lymph node biopsy and/or axillary lymph node dissection.

Women are encouraged to talk with their doctors about which surgical option is right for them. Also, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects from the specific surgery you will have.

More aggressive surgery, such as a mastectomy, is not always better and may cause more complications. The combination of lumpectomy and radiation therapy has a slightly higher risk of the cancer coming back in the same breast or the surrounding area. However, the long-term survival of women who choose lumpectomy is exactly the same as those who have a mastectomy. Even with a mastectomy, not all breast tissue can be removed and there is still a chance of recurrence.

Women with a very high risk of developing a new cancer in the other breast may consider a bilateral mastectomy, meaning both breasts are removed. This includes women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations and women with cancer in both breasts. For women not at very high risk of developing a new cancer in the future, having a healthy breast removed in a bilateral mastectomy neither prevents cancer recurrence nor improves a woman’s survival. Although the risk of getting a new cancer in that breast will be lowered, more extensive surgery may be linked with a greater risk of complications.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is the use of high-energy x-rays or other particles to destroy cancer cells. A doctor who specializes in giving radiation therapy to treat cancer is called a radiation oncologist. The most common type of radiation treatment is called external-beam radiation therapy, which is radiation given from a machine outside the body. When radiation treatment is given using a probe in the operating room, it is called intra-operative radiation therapy. When radiation therapy is given by placing radioactive sources into the tumor, it is called brachytherapy. Although the research results are encouraging, intra-operative radiation therapy and brachytherapy are not widely used. Where available, they may be options for patient with a small tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes. Learn more about the basics of radiation therapy.

A radiation therapy regimen, or schedule (see below), usually consists of a specific number of treatments given over a set period of time. Radiation therapy often helps lower the risk of recurrence in the breast. In fact, with modern surgery and radiation therapy, recurrence rates in the breast are now less than 5% in the 10 years after treatment, and survival is the same with lumpectomy or mastectomy. If there is cancer in the lymph nodes under the arm, radiation therapy may also be given to the same side of the neck or underarm near the breast or chest wall.

Radiation therapy may be given after or before surgery:

Adjuvant radiation therapy is given after surgery. Most commonly, it is given after a lumpectomy, and sometimes, chemotherapy. Patients who have a mastectomy may not need radiation therapy, depending on the features of the tumor. Radiation therapy may be recommended after mastectomy for a patient with a larger tumor, for those with cancer in many lymph nodes, for those with cancer cells outside of the capsule of the lymph node, and for those whose cancer has grown into the skin or chest wall, as well as other reasons.

Neoadjuvant radiation therapy is radiation therapy given before surgery to shrink a large tumor, which makes it easier to remove. This approach is uncommon and is only considered when a tumor cannot be removed with surgery.

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, including fatigue, swelling of the breast, redness and/or skin discoloration/hyperpigmentation and pain/burning in the skin where the radiation was directed, sometimes with blistering or peeling. Your doctor can recommend topical medication to apply to the skin to treat some of these side effects.

Very rarely, a small amount of the lung can be affected by the radiation, causing pneumonitis, a radiation-related swelling of the lung tissue. This risk depends on the size of the area that received radiation therapy, and this tends to heal with time.

In the past, with older equipment and radiation therapy techniques, women who received treatment for breast cancer on the left side of the body had a small increase in the long-term risk of heart disease. Modern techniques are now able to spare the vast majority of the heart from the effects of radiation therapy.

Many types of radiation therapy may be available to you with different schedules (see below). Talk with your doctor about the advantages and disadvantages of each option.

Radiation therapy schedule

Radiation therapy is usually given daily for a set number of weeks.

After a lumpectomy. Standard radiation therapy after a lumpectomy is external-beam radiation therapy given Monday through Friday for 5 to 6 weeks. This often includes radiation therapy to the whole breast the first 4 to 5 weeks, followed by a more focused treatment to where the tumor was located in the breast for the remaining treatments.

This focused part of the treatment, called a boost, is standard for women with invasive breast cancer to reduce the risk of a recurrence in the breast. Women with DCIS may also receive the boost. For women with a low risk of recurrence, the boost may be optional. It is important to discuss this treatment approach with your doctor.

After a mastectomy. For those who need radiation therapy after a mastectomy, it is usually given 5 days a week for 5 to 6 weeks. Radiation therapy can be given after reconstruction.

Newer regimens that shorten the length of standard radiation treatment are also in use. In a method called hypo-fractionated radiation therapy, a higher daily dose is given to the whole breast so that the overall length of treatment is shortened to 3 to 4 weeks. Large studies show that women with early-stage breast cancer who received this therapy have shown equal cure rates, equal and very low risks for complications, and equal or better appearance of the breasts 10 years after treatment when compared with standard radiation therapy. Hypo-fractionated radiation therapy can be combined with a boost to the tumor site either during or after the whole breast radiation treatments. Even shorter schedules have been studied and are in use in some centers, including accelerated partial breast radiation therapy (see below) for 5 days.

Research studies have shown that these shorter schedules are similarly safe and control the cancer as well as longer radiation treatment schedules in patients when lymph nodes are not involved, called node-negative breast cancer. These shorter schedules are becoming more accepted in the United States for cancers that have a lower risk of recurrence, and are a way to improve the convenience and reduce the time needed to finish radiation therapy (see also partial breast irradiation below).

These shorter schedules may not be options for women who need radiation therapy after a mastectomy or radiation therapy to their lymph nodes. Also, longer schedules of radiation therapy may be needed for some women with very large breast size. More research is being done to find out whether younger patients or those who need radiation therapy after chemotherapy may be able to have these shorter radiation therapy schedules.

Partial breast irradiation. Partial breast irradiation (PBI) is radiation therapy that is given directly to the tumor area instead of the entire breast. It is more common after a lumpectomy. Targeting radiation directly to the tumor area more directly usually shortens the amount of time that patients need to receive radiation therapy. However, only some patients may be able to have PBI. Although early results have been promising, PBI is still being studied. It is the subject of a large, nationwide clinical trial, and the results on the safety and effectiveness compared with standard radiation therapy are not yet ready. This study will help find out which patients are the most likely to benefit from PBI.

PBI can be done with standard external-beam radiation therapy that is focused on the area where tumor was removed and not on the entire breast. PBI may also be done with brachytherapy. Brachytherapy includes the use of plastic catheters or a metal wand placed temporarily in the breast. Breast brachytherapy can involve short treatment times, ranging from 1 dose to 1 week. It can also be given as 1 dose in the operating room immediately after the tumor is removed. These forms of focused radiation therapy are currently used only for patients with a smaller, less-aggressive, and lymph node-negative tumor.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is a more advanced way to give external-beam radiation therapy to the breast. The intensity of the radiation directed at the breast is varied to better target the tumor, spreading the radiation more evenly throughout the breast. The use of IMRT lessens the radiation dose and may decrease possible damage to nearby organs, such as the heart and lung, and the risks of some immediate side effects, such as peeling of the skin during treatment. This can be especially important for women with medium to large breasts who have a higher risk of side effects, such as peeling and burns, compared with women with smaller breasts. IMRT may also help to lessen the long-term effects on the breast tissue that were common with older radiation techniques such as hardness, swelling, or discoloration.

IMRT is not recommended for everyone. Talk with your radiation oncologist to learn more. Special insurance approval may also be needed for coverage for IMRT. It is important to check with your health insurance company before any treatment begins to make sure it is covered.

Proton therapy. Standard radiation therapy for breast cancer uses x-rays, also called photon therapy, to kill cancer cells. Proton therapy is a type of external-beam radiation therapy that uses protons rather than x-rays. At high energy, protons can destroy cancer cells. Protons have different physical properties that may allow the radiation therapy to be more targeted than photon therapy and potentially reduce the radiation dose. The therapy may also reduce the amount of radiation that goes near the heart. Researchers are studying the benefits of proton therapy versus photon therapy in a national clinical trial. But currently, proton therapy is an experimental treatment and may not be widely available.

Adjuvant radiation therapy concerns for older patients and/or those with a small tumor

Recent research studies have looked at the possibility of avoiding radiation therapy for women age 70 or older with an ER-positive, early-stage tumor (see Introduction), or for those women with a small tumor. Overall, these studies show that radiation therapy reduces the risk of breast cancer recurrence in the same breast, compared with no radiation therapy. However, radiation therapy does not lengthen women’s lives.

Guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) continue to recommend radiation therapy as the standard option after lumpectomy. However, they note that women with special situations or a low-risk tumor could reasonably choose not to have radiation therapy and use only systemic therapy (see below) after lumpectomy. This includes women age 70 or older or those with other medical conditions that could limit life expectancy within 5 years. People who choose this option must be willing to accept a modest increase in the risk that the cancer will come back in the breast.

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapy is treatment taken by mouth or through a vein that gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells wherever they may be in the body. There are 3 general categories of systemic therapy used for early-stage and locally-advanced breast cancer: chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapy. Each treatment is described below in more detail. Treatment options are based on information about the cancer and your overall health and treatment preferences.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the use of drugs to destroy cancer cells, usually by ending the cancer cells’ ability to grow and divide. Chemotherapy is prescribed by a medical oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating cancer with medication.

Systemic chemotherapy gets into the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Common ways to give chemotherapy include an intravenous (IV) tube placed into a vein using a needle, an injection under the skin (subcutaneous) or into a muscle (intramuscular), or a pill or capsule that is swallowed (orally).

Chemotherapy may be given before surgery to shrink a large tumor and make surgery easier, called neoadjuvant chemotherapy. It may also be given after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence, called adjuvant chemotherapy.

A chemotherapy regimen, or schedule, usually consists of a specific number of cycles given over a set period of time. Chemotherapy may be given on many different schedules depending on what worked best in clinical trials for that specific type of regimen. It may be given once a week, once every 2 weeks (also called dose-dense), once every 3 weeks, or even once every 4 weeks. There are many types of chemotherapy used to treat breast cancer. Common drugs include:

Capecitabine (Xeloda)

Carboplatin (Paraplatin)

Cisplatin (Platinol)

Cyclophosphamide (Neosar)

Docetaxel (Docefrez, Taxotere)

Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil)

Epirubicin (Ellence)

Fluorouracil (5-FU, Adrucil)

Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

Methotrexate (multiple brand names)

Paclitaxel (Taxol)

Protein-bound paclitaxel (Abraxane)

Vinorelbine (Navelbine)

Eribulin (Halaven)

Ixabepilone (Ixempra)

A patient may receive 1 drug at a time or combinations of different drugs given at the same time. Research has shown that combinations of certain drugs are sometimes more effective than single drugs for adjuvant treatment. The following drugs or combinations of drugs may be used as adjuvant therapy for early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer:

AC (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide)

AC or EC (epirubicin and cyclophosphamide) followed by T (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, followed by paclitaxel or docetaxel, or the reverse)

CAF (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU)

CEF (cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and 5-FU)

CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-FU)

EC (epirubicin, cyclophosphamide)

TAC (docetaxel, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide)

TC (docetaxel and cyclophosphamide)

Therapies that target the HER2 receptor may be given with chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer (see Targeted therapy, below). An example is the antibody trastuzumab. Combination regimens for HER2-positive breast cancer may include:

ACTH (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, trastuzumab)

TCH (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab)

TH (paclitaxel, trastuzumab)

THP (paclitaxel or docetaxel, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

TCHP (docetaxel, carboplatin, trastuzumab, pertuzumab)

The side effects of chemotherapy depend on the individual, the drug(s) used, and the schedule and dose used. These side effects can include fatigue, risk of infection, nausea and vomiting, hair loss, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. These side effects can often be very successfully prevented or managed during treatment with supportive medications, and they usually go away after treatment is finished. Rarely, long-term side effects may occur, such as heart damage, nerve damage, or secondary cancers. Many patients feel well during chemotherapy treatment and are active taking care of their families, working, and exercising during treatment, although each person’s experience can be different. Talk with your health care team about the possible side effects of your specific chemotherapy plan.

Learn more about the basics of chemotherapy and preparing for treatment. The medications used to treat cancer are continually being evaluated. Talking with your doctor, oncology nurse, or pharmacist is often the best way to learn about the medications prescribed for you, their purpose, and their potential side effects or interactions with other medications. Learn more about your prescriptions by using searchable drug databases.

Hormonal therapy

Hormonal therapy, also called endocrine therapy, is an effective treatment for most tumors that test positive for either estrogen or progesterone receptors (called ER-positive or PR-positive; see Introduction). This type of tumor uses hormones to fuel its growth. Blocking the hormones can help prevent a cancer recurrence and death from breast cancer when used either by itself or after adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Hormonal therapy may be given before surgery to shrink a tumor and make surgery easier. This approach is called neoadjuvant hormonal therapy. It may also be given after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence. This is called adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Tamoxifen. Tamoxifen is a drug that blocks estrogen from binding to breast cancer cells. It is effective for lowering the risk of recurrence in the breast that had cancer, the risk of developing cancer in the other breast, and the risk of distant recurrence. It is also approved by the FDA to reduce the risk of breast cancer in women at high risk for developing breast cancer and for lowering the risk of a local recurrence for women with DCIS who have had a lumpectomy. Tamoxifen works well in women who have been through menopause and those who have not.

Tamoxifen is a pill that is taken daily by mouth. It is important to discuss any other medications or supplements you take with your doctor, as there are some that can interfere with tamoxifen. Common side effects of tamoxifen include hot flashes as well as vaginal dryness, discharge or bleeding. Very rare risks include a cancer of the lining of the uterus; cataracts; and blood clots. However, tamoxifen may improve bone health and cholesterol levels.

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs). AIs decrease the amount of estrogen made in tissues other than the ovaries in postmenopausal women by blocking the aromatase enzyme. This enzyme changes weak male hormones called androgens into estrogen when the ovaries have stopped making estrogen during menopause. These drugs include anastrozole (Arimidex), exemestane (Aromasin), and letrozole (Femara). All of the AIs are pills taken daily by mouth. Only women who have been through menopause can take AIs. Treatment with AIs, either alone or following tamoxifen, can be as effective as taking tamoxifen alone at reducing the risk of recurrence in post-menopausal women.

The side effects of AIs may include muscle and joint pain, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, an increased risk of osteoporosis and broken bones, and increased cholesterol levels. Research shows that all 3 AI drugs work equally well and have similar side effects. However, women who have undesirable side effects while taking 1 AI may have fewer side effects with another AI for unclear reasons.

Women who have not gone through menopause should not take AIs, as they do not block the effects of estrogen made by the ovaries. Often, doctors will monitor blood estrogen levels in women whose periods have recently stopped, or those whose periods stop with chemotherapy to be sure that the ovaries are no longer producing estrogen.

Women who have gone through menopause and are prescribed hormonal therapy have several options:

Start therapy with an AI for up to 5 years

Begin treatment with tamoxifen for 2 to 3 years and then switch to an AI for 2 to 3 years

Take tamoxifen for 5 years then switch to an AI for up to 5 years, in what is called extended hormonal therapy

Research shows that taking tamoxifen for up to 10 years can further reduce the risk of recurrence following a diagnosis of early-stage and locally advanced breast cancer. However, side effects are also increased with longer duration of therapy. Learn more about ASCO's recommendations for hormonal therapy for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

Hormonal therapy for premenopausal women

As noted above, premenopausal women should not take AIs, as they will not work. Options for adjuvant hormonal therapy for premenopausal women include the following:

5 or more years of tamoxifen, possibly switching to an AI after menopause begins

Either tamoxifen or an AI combined with suppression of ovarian function. One of the oldest hormone treatments for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer is to stop the ovaries from making estrogen, called ovarian suppression. Medications called gonadotropin or luteinizing releasing hormone (GnRH or LHRH) analogues stop the ovaries from making estrogen, causing temporary menopause. Goserelin (Zoladex) and leuprolide (Lupron) are drugs given by injection that can stop the ovaries from making estrogen for 1 to 3 months. These drugs are given with tamoxifen or AIs as part of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Surgical removal of the ovaries, which is a permanent way to stop the ovaries from working, may also be considered in certain situations.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that targets the cancer’s specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment that contributes to cancer growth and survival. These treatments are very focused and work differently than chemotherapy. This type of treatment blocks the growth and spread of cancer cells while limiting damage to healthy cells.

Recent studies show that not all tumors have the same targets. To find the most effective treatment, your doctor may run tests to identify the genes, proteins, and other factors in your tumor. In addition, many research studies are taking place now to find out more about specific molecular targets and new treatments directed at them. Learn more about the basics of targeted treatments.

The first approved targeted therapies for breast cancer were hormonal therapies. Then, HER2-targeted therapies were approved to treat HER2-positive breast cancer. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects of specific medications and how they can be managed.

HER2-targeted therapy

Trastuzumab. This drug is approved as a therapy for non-metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer. Currently, patients with stage I to stage III breast cancer (see Stages) should receive a trastuzumab-based regimen often including a combination of trastuzumab with chemotherapy, followed by completion of 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab. Patients receiving trastuzumab have a small (2% to 5%) risk of heart problems. This risk is increased if a patient has other risk factors for heart disease or receives chemotherapy that also increases the risk of heart problems at the same time. These heart problems may go away and can be treatable with medication.

Pertuzumab (Perjeta). This drug is approved as part of neoadjuvant treatment for breast cancer in combination with trastuzumab and chemotherapy.

Ado-trastuzumab emtansine or T-DM1 (Kadcyla). T-DM1 is a combination of trastuzumab linked to a type of chemotherapy. This allows the drug to deliver chemotherapy into the cancer cell while reducing the chemotherapy received by healthy cells. T-DM1 is approved to treat metastatic breast cancer, and studies are now testing T-DM1 as a treatment for early-stage breast cancer.

Neratinib (Nerlynx). This oral drug is approved as a treatment for higher-risk HER2-positive, early-stage breast cancer. It is taken for a year, starting after patients have finished 1 year of trastuzumab.

Bone modifying drugs

Bone modifying drugs block bone destruction and help strengthen bone. They may be used to prevent cancer from recurring in the bone or to treat cancer that has spread to the bone. Certain types are also used in low doses to prevent and treat osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is the thinning of the bones.

There are 2 types of drugs that block bone destruction:

Bisphosphonates. These block the cells that destroy bone, called osteoclasts.

Denosumab (Xgeva). An osteoclast-targeted therapy called a RANK ligand inhibitor.

For people with breast cancer that has not spread, receiving bisphosphonates after breast cancer treatment may help to prevent a recurrence. ASCO recommends zoledronic acid (Zometa) or clodronate (multiple brand names) as options to help prevent a bone recurrence for women who have been through menopause. Clodronate is only available outside of the United States. Read ASCO’s recommendations for preventing a breast cancer recurrence in the bone.

Systemic therapy concerns for older patients

Age should never be the only factor used to determine treatment options. Systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy, often work as well for older patients as younger patients. However, older patients may be more likely to have side effects that impact their quality of life.

For example, older patients may have a higher risk of developing heart problems from trastuzumab. This is more common for patients who already have heart disease and for those who receive certain combinations of chemotherapy.

It’s important for all patients to talk with their doctors about the systemic therapy options recommended, including the benefits and risk. They should also ask about potential side effects and how they can be managed.

Getting care for symptoms and side effects

For people of all ages, cancer and its treatment can cause symptoms and side effects. In addition to treatments intended to slow, stop, or eliminate the cancer, an important part of cancer care is relieving a person’s symptoms and side effects. This approach is called supportive or palliative care, and it includes supporting the patient with his or her physical, emotional, and social needs.

Palliative care is any treatment that focuses on reducing symptoms, improving quality of life, and supporting patients and their families. Any person, regardless of age or type and stage of cancer, may receive palliative care. It works best when palliative care is started as early as needed in the cancer treatment process. People often receive treatment for the cancer at the same time they receive treatment to ease side effects. In fact, patients who receive both at the same time often have less severe symptoms, better quality of life, and report they are more satisfied with treatment.

Palliative treatments vary widely and often include medications, nutritional support, relaxation techniques, emotional support, and other therapies. You may also receive palliative treatments similar to those meant to eliminate the cancer, such as chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation therapy. Talk with your doctor about the goals of each option in your treatment plan.

Before treatment begins, talk with your health care team about the possible side effects of your specific treatment and palliative care options. During and after treatment, be sure to tell your doctor or another health care team member if you are experiencing a problem so it can be addressed as quickly as possible. Learn more about palliative care.

Recurrent breast cancer

If the cancer does return after treatment for early-stage disease, it is called recurrent cancer. When breast cancer recurs, it may come back in the following parts of the body:

The same place as the original cancer. This is called a local recurrence.

The chest wall or lymph nodes under the arm or in the chest. This is called a regional recurrence.

Another place, including distant organs such as the bones, lungs, liver, and brain. This is called a distant recurrence or a metastatic recurrence. For more information on a metastatic recurrence, see the Guide to Metastatic Breast Cancer.

When breast cancer recurs, a new cycle of testing will begin again to learn as much as possible about the recurrence. Testing may include imaging tests, such as those discussed in the Diagnosis section. In addition, another biopsy may be needed to confirm the breast cancer recurrence and learn about the features of the cancer.

After this testing is done, you and your doctor will talk about your treatment options. The treatment plan may include the treatments described above such as surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and hormonal therapy. They may be used in a different combination or at a different pace. The treatment options for recurrent breast cancer depend on the following factors:

Previous treatment(s) for the original cancer

Time since the original diagnosis

Location of the recurrence

Characteristics of the tumor, such as ER, PR, and HER2 status

Women with recurrent breast cancer often experience emotions such as disbelief or fear. Patients are encouraged to talk with their health care team about these feelings and ask about support services to help them cope. Learn more about dealing with cancer recurrence.

Treatment options for a local or regional breast cancer recurrence

A local or regional recurrence is often manageable and may be curable. The treatment options are explained below:

For women with a local recurrence in the breast after initial treatment with lumpectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy, the recommended treatment is mastectomy. Usually the cancer is completely removed with this treatment.

For women with a local or regional recurrence in the chest wall after an initial mastectomy, surgical removal of the recurrence followed by radiation therapy to the chest wall and lymph nodes is the recommended treatment. However, if radiation therapy has already been given for the initial cancer, this may not be an option. Radiation therapy cannot usually be given at full dose to the same area more than once.

Other treatments used to reduce the chance of a future distant recurrence include radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and targeted therapy. These are used depending on the tumor and the type of treatment previously received.

Whichever treatment plan you choose, palliative care will be important for relieving symptoms and side effects. Your doctor may suggest clinical trials that are studying new ways to treat this type of recurrent cancer.

The next section in this guide is About Clinical Trials. It offers more information about research studies that are focused on finding better ways to care for people with cancer. You may use the menu to choose a different section to read in this guide.

my mother inlaw died of breast cancer and my sister inlaw having the same problem ,I do realy hope there is already cure for this killer desease.Thanks for sharing this info .

its my pleasure.