Medical microbiology, mycobacteria and TB / Microbiologia medica, Micobatteri e TBC

Mycobacteria

Within the genus of mycobacteria there are several different species that may be responsible for slightly different diseases; in this article we will define the general characteristics that distinguish this genus.

Characteristics

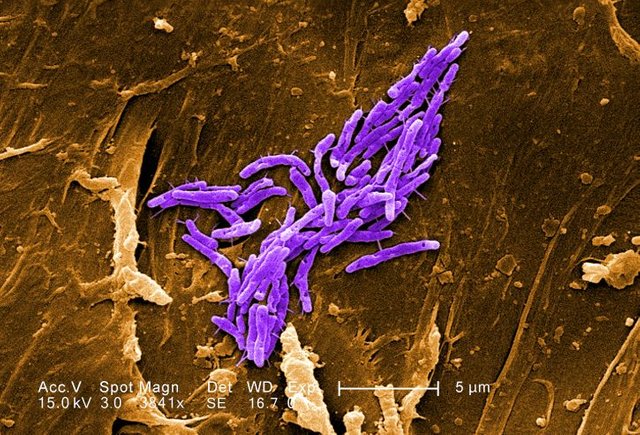

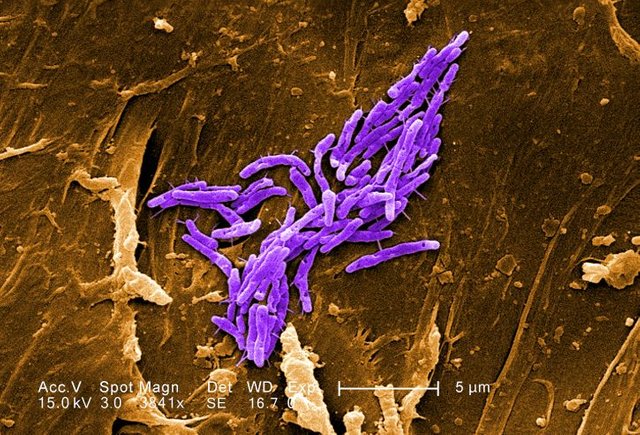

Mycobacteria are obligatory aerobic bacteria, immobile and aspigenous. They present under the microscope as bacilli and can reach very elongated forms, up to 10µm , therefore, from the microscopic point of view, they are easily detectable even at a first glance. They are characterized by their structure: they have an unusual wall strongly hydrophobic as it is composed of 60% lipids and 15% protein, in particular, the lipid component is basically represented by mycolic acids and waxes. The highly hydrophobic wall makes these bacteria acid-resistant, and this is a key feature that gives them some peculiarities also responsible for the pathogenetic power they possess: they resist many disinfectants, as well as drying, heat and UV rays.

They are able to last even in the environment, so it could be said that a wall so formed facilitates their spread. Considering the high percentage of lipids in the wall, it can also be said that the growth rate of these microorganisms is different from that of the bacteria studied so far: the latter replicate in about 20 minutes (22min. in the case of E.coli), while with mycobacteria we are in the order of a new cell division that lasts between 12 and 24 hours. The bacterial metabolism is also different.

Mycobacterium tubercolosis is an obligatory, immobile, asporiginal and highly diffused aerobic stick microorganism: tuberculosis, a contagious infectious disease, is in fact caused, in 90% of cases, by this bacillus.

It is distinguishable under the microscope because it tends to aggregate because of a chord factor that also has two other very important tasks:

1- It inhibits phagocytosis, thus managing to escape very well from the immune system;

2- Inhibits the fusion of the phagosome (i.e. the internalized mycobacterium) with the lysosomes, which are organelles rich in degrading enzymes that should destroy the mycobacterium. This factor is very important because it makes the mycobacteria able to resist even within the alveolar macrophages.

Colouring of Gram

Analyzing the structure of the Gram-positive and Gram-negative we have seen that

Gram positive: the plasma membrane has a double phospholipid layer and a single (but thicker) layer of peptidoglycan

Gram-negative: there is a thin layer of peptidoglycan between the inner and outer membranes with periplasmic space, any portions for external exchanges and LPS in the outer membrane.

Mycobacteria may in some respects resemble Gram-positives: a cytoplasmic membrane and a thick layer of peptidoglycan can be seen, but there is no external membrane. However, mycobacteria are not coloured by staining with Gram.

Structure of the peptidoglycan of mycobacteria

The peptidoglycan layer is bound externally to polysaccharides called arabinogalactans, whose terminals are esterified to mycolic acids that will form the outer lipid wall, which will make the bacteria very resistant; internally there is a whole series of lipids in different forms: free lipids, glycolipids and peptidoglycolipids.

On the outside, the peptide chains are called PPD (purified protein derivative), and these proteins are important because they represent antigens capable of stimulating our immune response: they are in fact responsible for type IV hypersensitivity reactions. PPD is in fact used in clinical practice to carry out an intradermal injection into the forearm in order to ascertain whether or not a type IV hypersensitivity reaction occurs, which in turn manifests itself with a reddish halo of inflammation at the level of the injection. We therefore refer to this concept when we talk about a highly hydrophobic antigenic component.

In summary, the high lipid percentage at wall level makes the mycobacteria:

- Waterproof and difficult to colour (other colours are used, not Gram);

- Resistant to acid and alkaline compounds, which will help from a certain point of view to operate a certain discrimination;

- Resistant to many antibiotics;

- Subjects to slow growth, with a generation time ranging from 12-15 hours on average;

- Resistant to complement mediated osmotic lysis;

- Able to survive within macrophages, particularly in alveolar macrophages, i.e. they are the first cells they encounter at the level of the pulmonary alveoli.

Classification

The most used classification is Runyon: this is done on the basis of the ability of mycobacteria to produce pigments that can give them a coloring. Four classes of mycobacteria are recognized:

Photochromogens: Mycobacteria, which when exposed to intense light, produce a yellow carotenoid pigment.

Scotochromogens: damage to coloured colonies, always yellowish in colour. In this case the colouring does not depend on the exposure to light, in fact the colonies are coloured whether the culture is kept in the dark or in the light. Remember that in some species the production of pigment can be increased by exposure to light.

Non-photochromogens: Even if we expose them to light, the pale yellow pigment does not become a more intense colour.

Fast growth: Includes mycobacteria that can grow much faster than other groups. Often they give visible colonies in only 3-5 days, in the other mycobacteria it takes about 3 weeks to have a visible colony, so if bacteria grow very fast in the culture, you may think you are facing fast growing mycobacteria or, possibly, contaminating bacteria.

This species is mainly found in immunocompromised patients.

Classification of Runyon groups

In addition, a classification of Runyon groups can be made in relation to pathogenicity and frequency.

The mycobacteria we find most frequently belong to the so-called mycobacterium tubercolosis complex, of which mycobacterium tubercolosis, mycobacterium africanum and mycobacterium bovis should be mentioned.

- In the first group of Runyon (photochromogens), mycobacterium kansasii is the most frequent;

- Group 2 (scotochromogens) and group 3 (non-photochromogens) are not widespread;

- The mycobacteria of group 4 are again a little more frequent and include mycobacterium fortuitum, mycobacterium chelonae and mycobacterium abscessus.

Tuberculosis (TB)

Mycobacteria are responsible for tuberculosis, an infectious disease that, even if it affects the lungs, can still be generalized, disseminate and affect other body districts, such as meninges (in this case we speak of meningoencephalitis caused by mycobacterium tubercolosis), or lymph nodes, bones, the urogenital system and kidneys. It is essential to distinguish between primary and post primary TB.

Primary TB is the one that is contracted by an individual who has never encountered this type of mycobacteria before, so in this case the body develops a certain immunity that will then evolve towards healing.

Post-primary TB, on the other hand, involves a reactivation, or rather, an endogenous reinfection, which can also occur several years after the first infection.

Sources of infection and transmission

Patients affected by this microorganism release aerosol droplets into the environment by means of coughing, which can then be inhaled by nearby people. Therefore, the patient is defined as highly infectious and must be isolated when the microscopic examination of his sputum is positive for this microorganism. If you only come into contact once with a person suffering from tuberculosis, this does not mean that you can contract the disease immediately, since you have seen that you would need several repeated contacts with the same person to be able to get sick: ultimately, a single contact is not a guarantee that you can meet the infection.

It can also be said that mycobacteria, due to their structure and lipid wall, can survive in the environment for long periods of time even in conditions of drying and that therefore the infection can contract at a later time.

Groups at risk of tuberculosis

High risk groups for infection include

- Hospital staff, clinic staff, long-stay nursing home staff;

- Foreign people from countries with high rates of tuberculosis;

- Populations with poor sanitation resources;

- People with HIV;

- People with alcoholism problems and who use intravenous drugs;

- People who are in close contact with people who have or are suspected of having tuberculosis;

- Some racial and ethnic minorities;

- People living in mental institutions or long term care.

Groups with a high risk of developing an active infection when exposed to the micro-organism include:

- Children under 4 years of age;

- People with diseases that somehow debilitate the immune system.

Epidemiology

Tuberculosis is one of the oldest diseases and, among the ten leading causes of death in the world, is the second deadly infectious disease after HIV: it is estimated that a third of the world's population has been infected with mycobacterium, but that the disease has developed in only 5-10% of people infected. Although the incidence is quite high, the number of deaths is decreasing worldwide: in fact, by 2020 we want to achieve a further reduction in the number of individuals who die from tuberculosis.

Every year there are about 480 thousand new cases of strains that, precisely because they have acquired resistance, are called MDR-TB strains (multidrug-resistant tuberculosis), and this is due to the fact that immigration has favored the spread. There are about 1.4 million deaths from tuberculosis, 400 thousand of which are HIV positive, and that the countries most affected are those of South Africa, Mongolia, Burma, Indonesia, the Philippines, India and Pakistan, while, as regards the European continent, Portugal (the only Western country to present most cases), Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. In addition, reports show that in Europe there are about 60,000 cases of tuberculosis, of which 4% due to multiresistant strains (4.6% of patients infected with multiresistant strains are affected by HIV). In Italy, in particular, there are 3700 cases of tuberculosis (2.7% caused by multiresistant strains).

Pathogenic action

The inhaled mycobacteria reach the pulmonary alveoli, multiply at the level of the pulmonary epithelium where there are the alveolar macrophages, whose function is to phagocyte these mycobacteria that, however, have a high capacity of resistance within them; as a direct consequence of this, they can therefore continue to proliferate in these cells and escape the action of the immune system.

At a certain point phagocytes may be destroyed, so not only the previously phagocytized mycobacteria are poured out, but also the whole series of degrading enzymes present at a macrophagic level: this mechanism then recalls other immunity cells.

It is important to underline that the virulence of the mycobacterium is given by its capacity to resist inside the host cell and to continuously recall cells of the immune system; what we see in the patient, therefore, is more the effect of the immune system that, in the attempt to eliminate the mycobacterium, triggers an inflammatory reaction that leads to the formation of a tubercle at the pulmonary level. The disease is rather slow and this inflammatory situation, which then tends to chronicize, leads to the formation of granulomatous lesions responsible for the destruction of alveolar tissue and the formation of tubercle. Inflammation may spread, and therefore the formation of tubercles may also affect other organs.

Primary TB, initial phase

Primary tuberculosis, which we have seen in subjects who previously had no contact with the micro-organism, is contracted mainly by aerogen and has an initial phase in which the lesion occurs at the level of the middle or lower lobe of the lung: the mycobacterium is phagocytised, followed by the activation of an inflammatory process of the granulomatous type and, at this point, some tubercular bacilli can then be transported to the satellite lymph nodes by the lymphatic route. This phase, which may be slightly symptomatic or even asymptomatic, sees the formation of exudative lesions and leukocytes accumulate around the bacillus to try to eradicate it.

After about a month, the specific immune response (cell-mediated) develops, which foresees the occurrence of a series of tissue lesions due to the intense inflammatory response; furthermore, macrophages, activated by T lymphocytes, begin to accumulate and destroy the bacilli. At this point there is the formation of tubercle, a granulomatous lesion that in the central part presents a necrosis called caseosa where it will be possible to identify macrophages containing mycobacteria, an intermediate area with epithelial cells and finally a collar of fibroblasts and mononuclear cells that seek to delimit the inflammation.

This tubercle, when the lesion stops, goes through a process of fibrosis and calcification with permanence of mycobacteria which can remain vital even for long periods of time without proliferating; otherwise the lesion can be broken after necrosis, and in this case the content is poured into the circulation, a sort of cavity is formed and the microorganisms are disseminated by means of the blood circulation in other locations, besides the pulmonary one: can in fact reach the regional lymph nodes, liver, spleen, kidneys, bones and meninges.

It is important to emphasize that one or more tubercular lesions can expand leading to the destruction of large tissue areas causing chronic pneumonia, tubercular osteomyelitis or meningeal tuberculosis depending on the body district concerned; in extreme cases tubercules develop in the whole body, which gives rise to military tuberculosis, which happens in immunocompromised patients who are unable to limit the action of the microorganism. Symptoms of tuberculosis include generalized discomfort, weight loss, coughing with purulent and bloody mucus, chest pain, night sweats, poor excretion.

Progression of tuberculosis

As seen before, at the pulmonary level, the alveolar macrophage phagocytizes the bacilli which it releases when it dies, after some weeks; now, a casein necrosis forms and the tubercle is generating which, surrounded by fibroblasts, has, internally, mycobacteria which continue to replicate and which, once its rupture has occurred, they disseminate to other organs.

Reactivation of tuberculosis (post-primary tuberculosis)

A reactivation of tuberculosis may occur due to:

- Decreased immune system efficiency often associated with malnutrition, alcoholism, old age, severe stress, immunosuppressive therapies, diabetes and AIDS.

- Survival of the mycobacterium in a quiescent form within a tubercular lotion (in this case we speak of tuberculosis from endogenous reinfection); the pulmonary apexes, where the high pressure of oxygen favours mycobacterial growth, are the most affected

Progression of tubercular disease

Mycobacterium tubercolosis infects the individual via the respiratory tract. There are 2 possibilities:

In 10% of cases the mycobacterium is responsible for active disease;

In 90% of cases we are faced with healing and healing with cases of latency or quiescence.

If we are faced with the first of these two possibilities, there is the formation of tubercle (called the primary complex of Ghon) and the patient has a number of symptoms: anorexia, night sweats, fever, asthenia, cough production and weight loss. Of this 10%, 90% undergo healing and healing, the other 10% show the extension of the disease to extrapulmonary sites, among which the most affected are meninges, lymph nodes, bones, intestines or the entire body (as mentioned, in this case we speak of military TB) after dissemination of the mycobacterium.

If healing and scarring then occur, a permanence of latent mycobacteria in the scars with no signs or symptoms may occur. If the patient experiences immunosuppression due to a series of factors (malignant neoplasms, respiratory diseases, alcoholism, corticosteroid therapies, diabetes mellitus), 10% of the cases show a reactivation of tuberculosis (we speak of secondary tuberculosis), while 90% of patients do not have any disease.

Evidence of infection

Evidence of the presence of the infection includes:

Clinical symptoms;

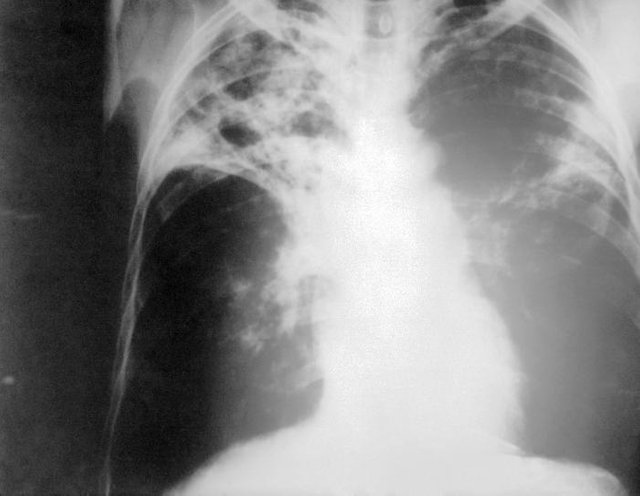

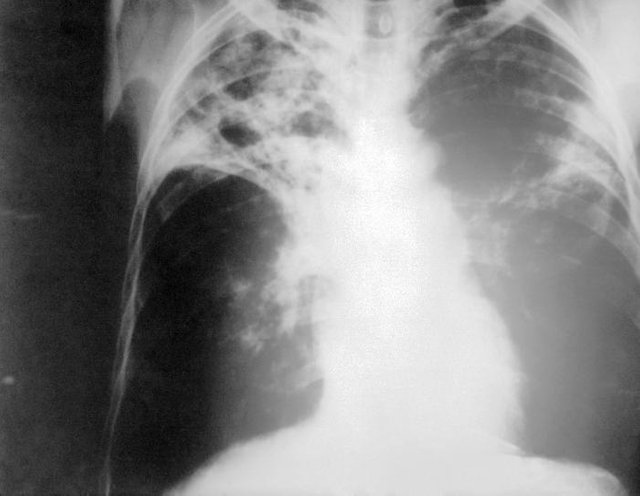

Radiographic investigations: these are useful in case of active disease because the primary complex of Ghon is visible;

Persistent positivity to the skin test (Mantoux test): this allows to differentiate the individuals infected with tbc from those not infected. The mantoux reaction is useful to verify the presence in an individual of an infection with mycobacterium tubercolosis: what is performed is an intradermal injection of ppd in the forearm and, after a period of time between 48 and 72 hours, it is assessed whether there is a hardening or a positive skin reaction to the injection. The reaction that should be observed is a reaction of delayed hypersensitivity conferred by that chord factor mentioned at the beginning of the lesson. In some cases, symptoms such as malaise and fever may also occur. The criteria for assessing the positivity of this test depend on the following parameters:

Hardening below 5 mm is considered a negative result

A hardening between 5 and 9 mm is considered intermediate (doubtful)

Hardening above 10 mm is considered positive.

Remember, however, that it is extremely important to assess, in addition to the hygienic and sanitary conditions in which he lives and the employment, the clinical history of the patient, to understand whether this has come into contact, for example, with individuals affected, or even, whether it is immunocompromised or affected by HIV.

In the case of primary tuberculosis, if the skin test for TB and X-ray are negative, in 10% of cases there is an active progressive primary infection and at this point the test and X-ray will be positive, as well as the excreted; in 90% of patients, however, there will be a latent-quiescent tuberculosis, with positive skin test and X-ray or positive or negative.

This manifestation of the infection does not lead to any disease in most cases, while in 10% of patients secondary tuberculosis (and therefore reactivation) may occur, and therefore the skin test, the X-ray and the excreted will be positive.

Laboratory diagnosis

The samples that arrive in the laboratory are respiratory and bronchial secretions are collected by different methods: we speak of bronchoaspirate, broncholavage, sputum. These are amplified after being treated with NALC-NaOH: the first is a fluidifying agent, while the second is a decontaminating agent that is used since, in the collection phase, the sample, passing through the oropharynx in which there is commensal flora, could encounter contamination.

The first thing to do is the microscopic examination that includes a series of steps such as purification and decontamination, essential for the next steps, namely the coloring and observation. The microscope allows to evaluate the infectivity of the person, but has a number of advantages and disadvantages:

Advantages: rapid examination (the report is ready in 24 hours), economic, detects the infectivity of the individual to be able to isolate infectious subjects;

Disadvantages: not very sensitive, not very specific investigation (other bacterial species, such as enocardia, could retain carbolfucsin in a variable way), false positives may occur, does not give information about the vitality of the bacterium.

Colours used:

- Ziehl-Neelsen staining (as recommended by the WHO): after depositing the sample on the slide and fixing it to the heat, a few drops of basic fuchsin are applied and washing with sulphuric acid and ethanol is carried out. This procedure causes all the bacterial cells to discolour, except for those of the mycobacterium which, thanks to the fuchsin itself, takes on a rather reddish colour.

At this point methylene blue is used as a contrast colour so that these micro-organisms are more evident and a series of further washes are carried out to eliminate the excess colour.

Ultimately, the alcohol-acid resistant organisms appear coloured in red, while the non-alcohol-acid resistant ones appear in blue.

- Fluorescent auramina-rodamine staining (i.e. Truant's fluorchromic method): is performed using fluorescent dyes and involves the use of a fluorescent microscope.

Beyond the microscope, which has a number of limitations, culture is considered the most effective method to make a diagnosis of tuberculosis. However, the reporting times of mycobacteria are in the order of 60 days, so the report could even reach the 59th day. For the formation of a bacterial culture it takes about 3-4 weeks. They are used:

Liquid soils: These are enrichment soils, which means that the bacteria grow faster than they would proliferate in solid soils.

Solid soils: The soil to be used is the Lowenstein-Jensen, a clarino-beak soil enriched with egg proteins that form the typical wall of the mycobacterium; it also contains malachite green, which is an antifungal and therefore ensures that these soils remain in the laboratory for long periods of time.

The procedure is as follows: the tubes are initially kept horizontal, then, after 24 hours from the moment in which the sample is absorbed on the surface of the agar, they are placed in a horizontal position and every 7 days, for the next 3-4 weeks, it is assessed whether or not the growth of the mycobacterium is verified. The colony is then collected and placed on the slide and the microorganisms are observed to be arranged: if there is a chord factor, these are aggregated with each other and one can guess that one is in front of the mycobacterium tubercolosis.

Another solid soil used is the Middlebrook soil; remember also another, but liquid, Middlebrook soil: in this case the detection of the bacterium takes place through an automated system known as MGIT: there are tubes with a silicone bottom containing a fluorescent compound sensitive to the resolution of the O2 voltage which, if consumed by the mycobacterium, represents a signal of bacterial growth. As the mycobacteria grow slowly, both solutions are used, so as to be sure to isolate the bacterium.

Once the colonies have been obtained, it is possible to check whether you are dealing with a mycobacterium or contaminating bacteria, then you go to evaluate the biochemical properties or, alternatively, you use probes that bind to the ribosomal subunit 16 S or possibly to other regions of DNA, or even, as a third option, you proceed with the sequencing of nucleic acids.

Recapitulation: microscopic evaluation of whether the slide has a mycobacterium or contaminating bacteria by staining, the colony is allowed to grow, then probes are used that can bind to the ribosomal subunit 16 S, evaluate the biochemical properties or make sequencing.

Use of amplification tests

The amplification tests, and therefore the molecular investigation, do not replace in any way either the microscopic examination (which detects the infectivity of the individual) or the cultural one (which, in addition to identifying with certainty the microorganism and confirm whether it is vital or not, allows you to perform an antibiogram to determine whether it is a resistant strain).

The amplification tests are to be performed only on selected samples; there are numerous kits on the market, even if those validated are those on respiratory samples. These tests are not used to monitor the therapy: the only way to do this is to send samples again and assess, by microscopic and cultural investigation, the presence of the mycobacterium.

Recapitulating: if the microscopy is positive, a molecular biology can be carried out to verify if you are in front of a mycobacterium or another type of microorganism; at this point, if this also gives a positive result, it can be said that the patient is suffering from tuberculosis and we proceed with molecular tests to assess the resistance to drugs, while if it gives a negative result we expect the result of the culture test.

If the microscopy is negative, molecular biology is used and if the latter is positive, a second sample is used to assess whether there is actually a positive result, while if it is negative, the culture test is awaited.

Treatment of tuberculosis

To avoid creating resistance, multitherapy is adopted and the main drugs used are:

- Isoniazide: inhibits synthesis of mycolic acids, then acts at the level of the wall of the mycobacterium;

- Rifampicin: inhibits bacterial RNA polymerase;

- Ethambutol: inhibits the transfer of arabinose to the cell wall;

- Streptomycin: inhibits protein synthesis;

- Pyrazinamide: used for its efficacy and acceptable toxicity.

If the drugs are effective, the smears excreted with acid resistant bacteria become negative and the patient will no longer be infectious after 2-3 weeks. However, there are multi-drug resistant strains: MDR-TB strains are resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin, while XDR-TB strains are resistant to rifampicin, fluoroquinolones and other drugs such as kanamycin, capreomycin and amylacin.

Tubercular disease therapy

Pyrazinamide, ethambutol, isoniazid and rifampicin are used in the attack phase.

From 2 to 6 months, isoniazid and rifampicin are administered.

In the case of latent tuberculosis, only isoniazid is used for 6 months or a year.

If, on the other hand, the strain is resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin, 5/7 second-line drugs, i.e. fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides, are combined in the first 3 months and therapy is continued for at least another 12 months.

Early identification of drug resistance before chemotherapy begins may decrease morbidity, mortality and treatment costs.

Prevention

For tuberculin-positive and asymptomatic individuals, chemotherapeutic treatment with isoniazid alone is indicated.

There is also a vaccine, the BCG, which uses the bacillus Calmette-Gyèrin, a live and attenuated strain of mycobacterium bovis, which stimulates the activation of macrophages that kill the pathogen; however, this vaccine provides 80% protection.

An all-Italian drug!

Rifampicin, the antibiotic of great validity in the treatment of tuberculosis, was discovered in 1959 in the Lepetit laboratories in Milan thanks to the Italian microbiologist Ermes Pagani and his team.

Evolution in the treatment of Tuberculosis, the History

Until the early 1900's tuberculosis was a chronic progressive disease, patients were placed in numerous sanatoriums, closed in these controlled houses so that the infection did not spread to the population through coughing, waiting for the course of the disease led to their death.

The sanatoriums were therefore places with good air, often near the woods, where patients could have greater relief during the course of the disease. There was no therapy: at best they could live longer thanks to the use of chemotherapy drugs (usually sulphonamides).

With the arrival of Rifampicin there is finally a cure for this disease that over the centuries has made many victims: the Sanatori cease to exist, the treatment consisted of 6 months-12 months of therapy, causing great difficulties to the liver and kidneys of these patients, but leading to a complete recovery from tuberculosis.

Today, it is perhaps used a little too often at a community level: in the case of bacterial meningitis in a class, subjects who have been in contact with the patient are treated with a prophylaxis based on rifampicin, one of the most powerful antibiotics.

This is wrong because the bacteria could develop resistance to it and transfer this resistance to mycobacteria, making them so insensitive to this drug.

I micobatteri

All’interno del genere dei micobatteri vi sono più specie diverse che possono essere responsabili di patologie leggermente differenti; in questo articolo verranno definite le caratteristiche generali che distinguono tale genere.

Caratteristiche

I micobatteri sono batteri aerobi obbligati, immobili e asporigeni. Si presentano al microscopio come bacilli e possono raggiungere forme molto allungate, fino ad arrivare ai 10µm , quindi dal punto di vista microscopico sono facilmente individuabili anche a una prima occhiata. Si caratterizzano per loro la struttura: possiedono infatti una parete insolita fortemente idrofobica in quanto è composta per il 60% da lipidi e per il 15% da proteine; in particolare, la componente lipidica è fondamentalmente rappresentata da acidi micolici e da cere .La parete altamente idrofobica rende questi batteri acido-resistenti, e questa è una caratteristica fondamentale che conferisce loro alcune peculiarità responsabili anche del potere patogenetico che possiedono: resistono a molti disinfettanti, così come all’essiccamento, al calore e ai raggi UV.

Sono in grado di perdurare anche nell’ambiente, quindi si potrebbe affermare che una parete così costituita faciliti la loro diffusione. Considerata l’elevata percentuale lipidica all’interno della stessa, si può inoltre affermare che il ritmo di crescita di questi microrganismi è diverso rispetto a quello dei batteri studiati fino ad oggi: questi ultimi replicano in circa 20 minuti ( 22min. nel caso di E.coli), mentre con i micobatteri ci troviamo nell’ordine di una nuova divisione cellulare che ha una durata compresa tra le 12 e le 24 ore. Differente risulta essere anche il metabolismo batterico.

Il mycobacterium tubercolosis è un microrganismo bastoncellare aerobio obbligato, immobile, asporigeno e altamente diffuso: la tubercolosi, malattia infettiva contagiosa, è infatti provocata, nel 90% dei casi, da questo bacillo.

Risulta distinguibile al microscopio in quanto ha tendenza ad aggregare per via di un fattore cordale che presenta anche altri due compiti molto importanti:

1- Inibisce la fagocitosi, riuscendo quindi a sfuggire molto bene al sistema immunitario;

2- Inibisce la fusione del fagosoma (cioè il micobatterio internalizzato) con i lisosomi, che sono organelli ricchi di enzimi degradativi che dovrebbero andare a distruggere il micobatterio. Tale fattore è molto importante perché rende i micobatteri in grado di resistere anche all’interno dei macrofagi alveolari.

Colorazione di Gram

Analizzando la struttura dei Gram-positivi e Gram-negativi si è visto che

• Gram positivi: la membrana plasmatica presenta un doppio strato fosfolipidico e un singolo strato (ma più spesso) di peptidoglicano

• Gram-negativi: tra la membrana interna e quella esterna è presente un sottile strato di peptidoglicano con spazio periplasmico, eventuali porine per gli scambi esterni e LPS nella membrana esterna.

I micobatteri potrebbero assomigliare sotto certi punti di vista ai Gram-positivi: si notano infatti una membrana citoplasmatica e uno spesso strato di peptidoglicano, risulta invece essere assente membrana esterna. Tuttavia, i micobatteri non si colorano mediante la colorazione di Gram.

Struttura del peptidoglicano dei micobatteri

Lo strato di peptidoglicano è legato esternamente a dei polisaccaridi chiamati arabinogalattani, i cui terminali sono esterificati ad acidi micolici che andranno a formare la parete lipidica esterna, la quale renderà i batteri molto resistenti; internamente vi è tutta una serie di lipidi sotto diverse forme: lipidi liberi, glicolipidi e peptidoglicolipidi.

Nella parte esterna le catene peptidiche sono definite PPD (derivato proteico purificato), e tali proteine sono importanti perché rappresentano antigeni in grado di stimolare la nostra risposta immunitaria: sono infatti responsabili di reazioni di ipersensibilità di tipo IV. Il PPD viene infatti utilizzato in pratica clinica per effettuare un’iniezione intradermica nell’avambraccio al fine di constatare se si verifichi o meno una reazione di ipersensibilità di tipo IV, che a sua volta di manifesta con un alone rossastro di infiammazione a livello dell’iniezione. Facciamo dunque riferimento a questo concetto quando parliamo di componente antigenica altamente idrofobica.

Ricapitolando, l’elevata percentuale lipidica a livello della parete rende i micobatteri:

• Impermeabili ai coloranti e difficilmente colorabili (si utilizzano altre colorazioni, non di Gram);

• Resistenti a composti acidi ed alcalini, il che aiuterà da un certo punto di vista a operare una certa discriminazione;

• Resistenti a molti antibiotici;

• Soggetti a lenta crescita, con un tempo di generazione che va dalle 12-15 ore di media;

• Resistenti alla lisi osmotica mediata dal complemento;

• In grado di sopravvivere all’interno dei macrofagi, in particolare nei macrofagi alveolari, ovvero sono le prime cellule che incontrano a livello degli alveoli polmonari.

Classificazione

La classificazione più usata è quella di Runyon: questa viene fatta sulla base della capacità dei micobatteri di produrre pigmenti che possono conferire loro una colorazione. Si riconoscono 4 classi di micobatteri:

Fotocromogeni: micobatteri, che esposti a luce intensa, producono un pigmento carotenoide giallo.

Scotocromogeni: danno delle colonie colorate, sempre di colore giallastro. In questo caso la colorazione non dipende dall’esposizione alla luce, infatti le colonie si vanno a colorare sia che si tenga la coltura al buio che alla luce. Si ricordi che in alcune specie la produzione di pigmento può essere incrementata con l’esposizione alla luce.

Nonfotocromogeni: anche se li esponiamo alla luce, il pigmento giallo pallido non diventa di un colore più intenso.

A rapida crescita: comprende micobatteri in grado di crescere molto più rapidamente degli altri gruppi. Spesso danno colonie visibili in soli 3-5 giorni, negli altri micobatteri si deve attendere circa 3 settimane per poter avere una colonia visibile; quindi se nella coltura dovessero crescere batteri molto velocemente, si potrebbe pensare di trovarsi davanti a dei micobatteri a rapida crescita o, eventualmente, a batteri contaminanti.

Questa specie si riscontra prevalentemente in pazienti immunodepressi.

Classificazione dei gruppi di Runyon

Inoltre si può fare una classificazione dei gruppi di Runyon in relazione alla patogenicità e alla frequenza.

I micobatteri che troviamo più frequentemente appartengono al cosiddetto mycobacterium tubercolosis complex, e di questi vanno citati il mycobacterium tubercolosis, il mycobacterium africanum, il mycobacterium bovis.

• Nel primo gruppo di Runyon (fotocromogeni) il mycobacterium kansasii è il più frequentemente;

• Il gruppo 2 (scotocromogeni) e il gruppo 3 (non fotocromogeni) sono poco diffusi;

• I micobatteri del gruppo 4 tornano ad essere un po’ più frequenti e di questi si ricordino il mycobacterium fortuitum, il mycobacterium chelonae e il mycobacterium abscessus.

Tubercolosi (TBC)

I micobatteri sono responsabili della tubercolosi, una malattia infettiva che, anche se colpisce i polmoni, può comunque presentare carattere generalizzato, disseminare e interessare altri distretti corporei, come ad esempio le meningi (in tal caso parliamo di meningoencefalite causata da mycobacterium tubercolosis), oppure i linfonodi, le ossa, l’apparato urogenitale e i reni. E’ fondamentale saper distinguere una TBC primaria da una post primaria.

• La TBC primaria è quella che viene contratta da un individuo che non ha mai incontrato prima questo tipo di micobatteri, quindi in tal caso l’organismo sviluppa una certa immunità che poi evolverà verso la guarigione.

• La TBC post primaria, invece, comporta una riattivazione, o meglio, una reinfezione endogena, che può verificarsi anche parecchi anni dopo la prima infezione.

Fonti d’infezione e trasmissione

I pazienti colpiti da questo microrganismo disperdono nell’ambiente, mediante colpi di tosse, goccioline di aerosol che possono poi essere inalate dalle persone vicine. Pertanto il paziente viene definito altamente infettivo e deve essere isolato nel momento in cui l’esame microscopico del suo espettorato risulta essere positivo a tale microrganismo. Se si viene a contatto solo una volta con una persona affetta da tubercolosi, non significa che si possa contrarre subito la malattia, dal momento che si è visto che servirebbero più contatti ripetuti con la stessa persona per potersi ammalare: in definitiva, un solo contatto non è garanzia del fatto che si possa andare incontro al contagio.

Si può inoltre affermare che i micobatteri, vista la loro struttura e parete lipidica, possono sopravvivere nell’ambiente per lunghi periodi di tempo anche in condizione di essiccazione e che dunque l’infezione si può contrarre in un secondo momento.

Gruppi a rischio tubercolosi

I gruppi ad alto rischio d’infezione comprendono:

• Personale ospedaliero, di cliniche, case di cura a lunga degenza;

• Persone straniere che provengono da paesi con alto tasso di tubercolosi;

• Popolazione con scarse risorse igienico-sanitarie;

• Persone affette da HIV;

• Persone con problemi di alcolismo e che fanno uso di droghe per endovena;

• Persone che sono a stretto contatto con persone che hanno o si sospetta abbiano la tubercolosi;

• Alcune minoranze razziali ed etniche;

• Persone che vivono in istituti mentali o a lunga degenza.

I gruppi che presentano un alto rischio di sviluppare un’infezione attiva una volta esposti al microrganismo comprendono invece:

• Bambini di età inferiore ai 4 anni;

• Persone con patologie che in qualche modo debilitano il sistema immunitario.

Epidemiologia

La tubercolosi è una delle più antiche malattie e, tra le dieci principali cause di morte nel mondo, è la seconda malattia infettiva letale dopo l’HIV: si stima appunto che un terzo della popolazione mondiale sia stata infettata dal micobatterio, ma che la malattia si sia sviluppata solo nel 5-10% delle persone contagiate. Nonostante l’incidenza sia piuttosto alta, il numero dei decessi è in diminuzione in tutto il mondo: infatti entro il 2020 si vuole giungere a un’ulteriore riduzione del numero di individui che muoiono per tubercolosi.

Ogni anno si registrano circa 480 mila nuovi casi di ceppi che, proprio perché hanno acquisito delle resistenze, sono definiti ceppi MDR-TB (multidrug-resistant tubercolosis), e questo è dovuto al fatto che l’immigrazione ne ha favorito la diffusione. Si contano circa 1,4 milioni decessi per tubercolosi, di cui 400 mila di individui HIV positivi, e che i Paesi più colpiti sono quelli del Sud Africa, Mongolia, Birmania, Indonesia, Filippine, India e Pakistan, mentre, per quanto riguarda il continente europeo, Portogallo (l’unico Paese occidentale a presentare la maggior parte dei casi), Romania, Bulgaria, Croazia, Polonia, Lituania, Lettonia ed Estonia. In più, da report si può osservare che in Europa si contano circa 60.000 casi di tubercolosi, di cui il 4% dovuti a ceppi multiresistenti (il 4.6% dei pazienti infettati da ceppi multiresistenti è affetto da HIV). In Italia, nello specifico, si registrano 3700 casi di tubercolosi (il 2.7 % causato da ceppi multiresistenti).

Azione patogena

I micobatteri inalati raggiungono gli alveoli polmonari, si moltiplicano a livello dell’epitelio polmonare dove vi sono i macrofagi alveolari, la cui funzione è quella di fagocitare tali micobatteri che tuttavia presentano un’elevata capacità di resistenza all’interno degli stessi; come diretta conseguenza di ciò, essi possono quindi continuare a proliferare in queste cellule e a sfuggire all’azione del sistema immunitario.

Ad un certo punto i fagociti possono andare incontro a distruzione, quindi vengono riversati all’esterno non solo i micobatteri fagocitati in precedenza, ma anche tutta quella serie di enzimi degradativi presenti a livello macrofagico: tale meccanismo richiama poi altre cellule dell’immunità.

E’ importante sottolineare che la virulenza del micobatterio è data dalla sua capacità di resistere all’interno della cellula ospite e di richiamare continuamente cellule del sistema immunitario; quello che noi vediamo nel paziente, dunque, è più che altro l’effetto del sistema immunitario che, nel tentativo di eliminare il micobatterio, scatena una reazione infiammatoria che porta alla formazione di un tubercolo a livello polmonare. La malattia è piuttosto lenta e questa situazione infiammatoria, che tende poi a cronicizzare, porta alla formazione di lesioni granulomatose responsabili della distruzione del tessuto alveolare e alla formazione del tubercolo. L’infiammazione potrebbe disseminarsi, e quindi la formazione di tubercoli potrebbe interessare anche altri organi.

TBC primaria, fase iniziale

La tubercolosi primaria, che abbiamo visto insorgere nei soggetti che in precedenza non hanno avuto contatti con il microrganismo, viene contratta prevalentemente per via aerogena e presenta una fase iniziale in cui la lesione si verifica a livello del lobo medio o inferiore del polmone: il micobatterio viene fagocitato, segue l’attivazione di un processo infiammatorio di tipo granulomatoso e, a questo punto, alcuni bacilli tubercolari possono essere poi trasportati nei linfonodi satelliti mediante la via linfatica. Questa fase, che può essere lievemente sintomatica o anche asintomatica, vede la formazione di lesioni essudative e i leucociti si accumulano attorno al bacillo per cercare di debellarlo.

Passato circa un mese, si sviluppa la risposta immunitaria specifica (cellulo-mediata) che prevede il verificarsi di una serie di lesioni tissutali dovute all’intensa risposta infiammatoria; inoltre, i macrofagi, attivati dai linfociti T, iniziano ad accumularsi e a distruggere i bacilli. A questo punto vi è la formazione del tubercolo, ossia una lesione granulomatosa che nella parte centrale presenta una necrosi detta caseosa dove sarà possibile individuare dei macrofagi contenenti micobatteri, una zona intermedia con cellule epiteliali e infine un collare di fibroblasti e cellule mononucleate che cercano delimitare l’infiammazione.

Questo tubercolo, quando la lesione si arresta, va incontro a un processo di fibrosi e calcificazione con permanenza di micobatteri che possono rimanere vitali anche per lunghi periodi di tempo senza proliferare; si può altrimenti rompere la lesione in seguito a necrosi, e in tal caso il contenuto viene riversato in circolo, si forma una specie di cavità e i microrganismi vengono disseminati per mezzo della circolazione ematica in altre sedi, oltre a quella polmonare: può infatti raggiungere i linfonodi regionali, fegato, milza, reni, ossa e meningi.

E’ importante sottolineare che una o più lesioni tubercolari possono espandersi portando alla distruzione di estese aree tissutali causando polmonite cronica, osteomielite tubercolare o tubercolosi meningea a seconda del distretto corporeo interessato; in casi estremi si sviluppano tubercoli nell’intero organismo, il che dà luogo a tubercolosi miliare, cosa che succede in pazienti immunocompromessi che non riescono a limitare l’azione del microrganismo. I sintomi della tubercolosi comprendono malessere generalizzato, perdita di peso, tosse con muco purulento e sanguinolento, dolore al petto, sudorazione notturna, escreato scarso.

Progressione della tubercolosi

Come visto in precedenza, a livello polmonare il macrofago alveolare fagocita i bacilli che rilascia quando muore, dopo alcune settimane; si forma ora una necrosi caseosa e si va generando il tubercolo che, circondato da fibroblasti, presenta internamente micobatteri che continuano a replicare e che, una volta verificatasi la sua rottura, disseminano ad altri organi.

Riattivazione della tubercolosi (tubercolosi post-primaria)

Si può verificare una riattivazione della tubercolosi per via di:

• Una diminuita efficienza del sistema immunitario spesso associata a malnutrizione, alcolismo, età avanzata, gravi stress, terapie immunosoppressive, diabete e AIDS.

• Sopravvivenza del micobatterio in forma quiescente all’interno di una lozione tubercolare (in tal caso si parla di tubercolosi da reinfezione endogena); gli apici polmonari, dove l’elevata pressione dell’ossigeno favorisce la crescita micobatterica, sono i più interessati

Progressione della malattia tubercolare

Il mycobacterium tubercolosis infetta l’individuo mediante le vie respiratorie. Vi sono 2 possibilità:

• Nel 10% dei casi il micobatterio è responsabile di malattia attiva;

• Nel 90% dei casi ci troviamo davanti a guarigione e cicatrizzazione con casi di latenza o quiescenza.

Se siamo di fronte alla prima di queste due possibilità, vi è la formazione del tubercolo (definito complesso primario di Ghon) e il paziente presenta una serie di sintomi: anoressia, sudorazione notturna, febbre, astenia, tosse produttiva e perdita di peso. Di questo 10%, il 90% va incontro a guarigione e cicatrizzazione, l’altro 10% manifesta l’estensione della malattia a siti extrapolmonari, tra cui i più colpiti sono meningi, linfonodi, ossa, intestino o all’intero organismo (come detto, in tal caso si parla di TBC miliare) in seguito a disseminazione del micobatterio.

Se poi si verificano guarigione e cicatrizzazione, si può manifestare una permanenza di micobatteri latenti nelle cicatrici con assenza di segni o sintomi. Se il paziente va incontro a immunosoppressione per via di una serie di fattori (neoplasie maligne, malattie respiratorie, alcolismo, terapie corticosteroidee, diabete mellito), nel 10% dei casi si manifesta una riattivazione della tubercolosi (si parla di tubercolosi secondaria), mentre nel 90% dei pazienti non si riscontra alcuna malattia.

Evidenze d’infezione

Le evidenze che attestano la presenza dell’infezione includono:

• Sintomatologia clinica;

• Indagini radiografiche: queste tornano utili in caso di malattia attiva perché è visibile il complesso primario di Ghon;

• Persistente positività al test cutaneo (test di Mantoux): questo permette di differenziare gli individui infetti da tbc da quelli non infetti. La reazione di mantoux risulta utile per verificare la presenza in un individuo di una infezione da mycobacterium tubercolosis: ciò che viene eseguita è un’iniezione intradermica di ppd nell’avambraccio e,dopo un lasso di tempo compreso tra le 48 e le 72 ore, si valuta se vi sia un indurimento o una reazione cutanea positiva all’iniezione. La reazione che si dovrebbe osservare è una reazione di ipersensibilità ritardata conferita da quel fattore cordale di cui si è fatto cenno all’inizio della lezione. In taluni casi si possono manifestare anche sintomi quali malessere e febbre. I criteri per valutare la positività di tale test dipendono dai seguenti parametri:

Un indurimento al di sotto dei 5 mm è considerato un risultato negativo

Un indurimento tra i 5 e i 9 mm è considerato intermedio (dubbio)

Un indurimento al di sopra dei 10 mm è considerato positivo.

Si ricordi comunque che è estremamente importante valutare, oltre alle condizioni igienico sanitarie in cui vive e l’occupazione lavorativa, la storia clinica del paziente, capire se questo sia venuto a contatto, per esempio, con individui affetti, o ancora, se sia immunocompromesso o affetto da HIV.

Nel caso di tubercolosi primaria, se il test cutaneo per la TBC e la radiografia risultano negativi, nel 10% dei casi si va incontro a un’infezione primaria progressiva attiva e a questo punto il test e la radiografia saranno positivi, così come l’escreato; nel 90% dei pazienti, invece, si manifesterà una tubercolosi latente-quiescente, con test cutaneo positivo e radiografia o positiva o negativa.

Tale manifestazione dell’infezione non porta ad alcuna malattia nella maggior parte dei casi, mentre nel 10% dei pazienti si potrebbe verificare tubercolosi secondaria (e quindi riattivazione), e dunque il test cutaneo, la radiografia e l’escreato risulteranno positivi.

Diagnosi di laboratorio

I campioni che arrivano in laboratorio sono di tipo respiratorio e le secrezioni bronchiali vengono raccolte mediante diverse metodiche: si parla di broncoaspirato, broncolavaggio, espettorato. Questi vengono sottoposti all’amplificazione dopo essere stati trattati con NALC-NaOH: il primo è un agente fluidificante, mentre il secondo è un agente decontaminante che viene utilizzato dal momento che, nella fase di prelievo, il campione, passando per l’orofaringe in cui vi è flora commensale, potrebbe andare incontro a contaminazione.

La prima cosa da fare è l’esame microscopico che prevede una serie di passaggi quali la purificazione e la decontaminazione, indispensabili per gli step successivi, e cioè la colorazione e l’osservazione. Il microscopio permette di valutare l’infettività della persona, ma presenta una serie di vantaggi e svantaggi:

• Vantaggi: esame rapido (in referto è pronto in24 ore), economico, rileva l’infettività dell’individuo per poter isolare i soggetti contagiosi;

• Svantaggi: indagine poco sensibile, poco specifica (altre specie batteriche, come l’enocardia, potrebbero trattenere in modo variabile la carbolfucsina), si possono verificare falsi positivi, non dà informazioni riguardo la vitalità del batterio.

Colorazioni utilizzate:

• La colorazione di Ziehl-Neelsen (come consigliato dall’Istituto Superiore di Sanità): dopo aver depositato il campione sul vetrino e averlo fissato al calore, si applicano poche gocce di fucsina basica e si procede con il lavaggio mediante acido solforico ed etanolo. Tale procedimento fa sì che tutte le cellule batteriche si vadano a decolorare; tranne quelle del micobatterio che assume, grazie alla fucsina stessa, una colorazione piuttosto rossastra.

A questo punto viene utilizzato il blu di metilene come colorazione di contrasto in modo che tali microrganismi siano maggiormente evidenti e si procede effettuando una serie di ulteriori lavaggi per eliminare il colorante in eccesso.

In definitiva, gli organismi alcool-acido resistenti appaiono colorati in rosso, mentre quelli non alcool-acido resistenti in blu.

• La colorazione con auramina-rodamina fluorescente (ossia il metodo fluorocromico di Truant): viene eseguita mediante coloranti fluorescenti e prevede l’utilizzo di un microscopio a fluorescenza.

Al di là del microscopio, che presenta una serie di limitazioni, la coltura viene considerata il metodo più efficace per effettuare una diagnosi di tubercolosi. Tuttavia, i tempi di refertazione dei micobatteri sono nell’ordine dei 60 giorni, quindi il referto potrebbe arrivare anche al 59esimo giorno. Perché si formi una coltura batterica sono necessarie circa 3-4 settimane. Vengono utilizzati:

Terreni liquidi: sono terreni di arricchimento, ciò significa che i batteri crescono più velocemente rispetto a quanto prolifererebbero nei terreni solidi.

Terreni solidi: Il terreno a cui si ricorre è il Lowenstein-Jensen, un terreno a becco di clarino, arricchito con proteine dell’uovo che costituiscono la parete tipica del micobatterio; esso contiene anche il verde di malachite che è un antifungino e quindi fa sì che questi terreni si mantengano in laboratorio per lunghi periodi di tempo.

La procedura è la seguente: i tubi sono mantenuti inizialmente orizzontali, poi, passate 24 ore dal momento in cui il campione risulta assorbito sulla superficie dell’agar, vengono messi in posizione orizzontale e ogni 7 giorni, per le 3-4 settimane successive, si valuta se sia verificata o meno la crescita del micobatterio. Si effettua poi un prelievo della colonia che viene messa sul vetrino e si osserva come i microrganismi sono disposti: se vi è il fattore cordale, questi risultano in aggregazione gli uni con gli altri e si può intuire che ci si trova davanti al mycobacterium tubercolosis.

Un altro terreno solido utilizzato è il terreno di Middlebrook; se ne ricordi anche un altro, però liquido, sempre Middlebrook: in questo caso la rilevazione del batterio avviene attraverso un sistema automatizzato noto come MGIT : vi sono provette con fondo di silicone contenenti un composto fluorescente sensibile alla risoluzione della tensione di O2 che, se consumato dal micobatterio, rappresenta un segnale di crescita batterica. Siccome i micobatteri crescono lentamente si utilizzano entrambe le soluzioni, in modo tale da essere sicuri di isolare il batterio

Una volta ottenute le colonie, è possibile verificare se ci si trova davanti a un micobatterio o a batteri contaminanti, quindi si vanno a valutare le proprietà biochimiche o, in alternativa, si utilizzano sonde che si legano alla subunità ribosomiale 16 S o eventualmente ad altre regioni di DNA, o ancora, come terza opzione, si procede con il sequenziamento degli acidi nucleici.

Ricapitolando: si valuta al microscopio se sul vetrino si ha un micobatterio o batteri contaminanti effettuando la colorazione, si lascia crescere la colonia, si utilizzano poi delle sonde in grado di legarsi alla subunità ribosomiale 16 S, valutare le proprietà biochimiche oppure fare sequenziamento.

Impiego dei test di amplificazione

I test di amplificazione, e quindi l’indagine molecolare, non sostituiscono in alcun modo né l’esame microscopico (che rileva l’infettività dell’individuo) né quello colturale (che, oltre a identificare con certezza il microrganismo e confermare se sia vitale o meno, permette di effettuare un antibiogramma per capire se si tratti di un ceppo resistente)

I test di amplificazione sono da eseguire solo su campioni selezionati; vi sono numerosi kit in commercio, anche se quelli validati sono quelli sui campioni respiratori . Tali test non vengono utilizzati per monitorare la terapia: l’unico modo per fare ciò è mandare nuovamente campioni e valutare, mediante indagine microscopica e colturale, la presenza del micobatterio.

Ricapitolando: se la microscopia risulta essere positiva, si può fare eventualmente una biologia molecolare per verificare se ci si trova davanti a un micobatterio o a un altro tipo di microrganismo; a questo punto, se anche questa dà esito positivo, si può affermare che il paziente è affetto da tubercolosi e si procede con test molecolari per valutare la resistenza ai farmaci, mentre se dà esito negativo si attende l’esito dell’esame colturale.

Se la microscopia risulta invece essere negativa, si procede mediante biologia molecolare e se quest’ultima dà esito positivo, viene effettuata su un secondo campione per valutare che vi sia effettivamente positività, mentre se è negativa si attende l’esame colturale.

Trattamento della tubercolosi

Per evitare di creare resistenze, si adotta una multiterapia e i principali farmaci utilizzati sono:

• Isoniazide: inibisce sintesi acidi micolici, quindi agisce a livello della parete del micobatterio;

• Rifampicina: inibisce RNA polimerasi batterica;

• Etambutolo: inibisce il trasferimento dell’arabinosio alla parete cellulare;

• Streptomicina: inibisce la sintesi proteica;

• Pirazinamide: utilizzata per la sua efficacia ed accettabile tossicità.

Se i farmaci sono efficaci, gli strisci di escreato con batteri acido resistenti diventano negativi e il paziente risulterà non più infettante dopo 2-3 settimane. Tuttavia vi sono dei ceppi multiresistenti a certi farmaci: i ceppi MDR-TB sono resistenti a isoniazide e rifampicina, mentre i ceppi XDR-TB lo sono a rifampicina, fluorochinoloni e ad altri farmaci come kanamicina, capreomicina e amilkacina.

Terapia della malattia tubercolare

Nella fase di attacco vengono utilizzati pirazinamide, etambutolo, isoniazide e rifampicina.

Dai 2 ai 6 mesi si continua poi a somministrare isoniazide e rifampicina.

Di fronte a una tubercolosi latente, per 6 mesi o un anno si procede solo mediante isoniazide.

Se invece il ceppo è resistente a isoniazide e rifampicina, nei primi 3 mesi vengono combinati 5/7 farmaci di seconda linea, ossia fluorochinoloni e aminoglicosidi, e si continua con la terapia per almeno altri 12 mesi.

L’identificazione precoce delle resistenze ai farmaci, prima dell’inizio della chemioterapia, può diminuire la morbilità, mortalità e i costi di trattamento.

Prevenzione

Per gli individui tubercolino-positivi e asintomatici è indicato il trattamento chemioterapico con la sola isoniazide.

E’ presente poi un vaccino che è il BCG dove si fa uso del bacillo Calmette-Gyèrin, ceppo vivo e attenuato di mycobacterium bovis, che stimola l’attivazione dei macrofagi i quali uccidono il patogeno; questo vaccino conferisce tuttavia una protezione pari all’80%.

Un farmaco tutto Italiano!

La Rifampicina, l'antibiotico di grandissima validità nella cura della tubercolosi è stata scoperta nel 1959 nei laboratori Lepetit a Milano grazie al Microbiologo italiano Ermes Pagani e al suo team.

Evoluzione nella cura della Tubercolosi, la Storia

Fino ai primi anni del 900 la tubercolosi era una malattia cronica progressiva, i pazienti venivano messi nei numerosi sanatori, chiusi in queste case controllate affinché l’infezione non si propagasse alla popolazione tramite la tosse, aspettando che il decorso della malattia li portasse alla morte.

I sanatori erano quindi dei luoghi con una buona aria, spesso vicino ai boschi, dove i pazienti potevano avere un maggiore sollievo durante il decorso della malattia. Non esisteva nessuna terapia: essi nel migliore dei casi potevano vivere più a lungo grazie all’utilizzo di farmaci chemioterapici (solitamente sulfamidici).

Con l’arrivo della Rifampicina si ha finalmente una cura per questa malattia che nel corso dei secoli ha fatto numerosissime vittime: i Sanatori cessano di esistere, la cura consisteva in 6 mesi-12 mesi di terapia, causando sì grandi difficoltà al fegato e ai reni di questi pazienti, ma portandoli ad una completa guarigione dalla tubercolosi.

Ad oggi essa viene utilizzata forse un po’ troppo spesso a livello comunitario: nel caso di una meningite batterica in una classe, i soggetti che sono stati a contatto con il paziente vengono trattati con una profilassi a base di rifampicina, uno degli antibiotici più potenti.

Questo è sbagliato perché i batteri potrebbero sviluppare una resistenza alla stessa e trasferire questa resistenza ai micobatteri, rendendoli cosi insensibili a questo farmaco.

Fonti/Sources

Immagini/Pictures

You know how many AFB cultures I process each night? At least 15-20. It's a painstaking process and like what you said about the stains, not very sensitive.

At my work, we use

BD BACTEC™ MGIT™ Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tubesalong with LJ slants. A "positive" culture is examined again with the Auramine stain method.If the culture is mixed, it is put on

Mitchison 7H11 Selective Agar. Best part, this isn't even close to the end if we have to look for Nocardia. Once isolated, we send them to a reference lab to test the sensitivities. It's madness.Aside from TB, pediatric/cancer patients make up the bulk of the AFB cultures at work. It's not uncommon to find some sort of acid fast bacillus lurking in wounds, etc.

I think that laboratory work is one of the most fundamental parts of the whole health care, it is very difficult and very precise and with different risks, people like you who do this work deserve a great deal of respect.

Questo post è stato condiviso e votato dal team di curatori di discovery-it.

This post was shared and voted by the curators team of discovery-it

Will the Mars explorers and citizens (generations) live in isolation from many viruses & bacteries?

At the moment there is no form of life on Mars, but no, men will never be isolated from viruses and bacteria, because they are within our organism and are fundamental, the so-called microbiome

Hello,

Your post has been manually curated by a @stem.curate curator.

We are dedicated to supporting great content, like yours on the STEMGeeks tribe.

Please join us on discord.

This post has been voted on by the SteemSTEM curation team and voting trail. It is elligible for support from @curie and @minnowbooster.

If you appreciate the work we are doing, then consider supporting our witness @stem.witness. Additional witness support to the curie witness would be appreciated as well.

For additional information please join us on the SteemSTEM discord and to get to know the rest of the community!

Please consider using the steemstem.io app and/or including @steemstem in the list of beneficiaries of this post. This could yield a stronger support from SteemSTEM.

Congratulations @riccc96! You have completed the following achievement on the Steem blockchain and have been rewarded with new badge(s) :

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOP