Kinetic Energy, one of the many forms of Energy

Kinetic Energy and Potential Energy

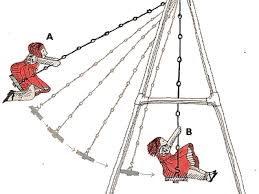

Energy comes in many forms, all with different definitions since it derives itself from an intangible factor and has no body or size. In certain cases, the energy itself will refer to the movement generated thanks to natural resources, but in others, we will have to speak in terms of mechanics. Thus, in the world, we use different types of energy such as electricity, light, thermal, wind, solar, geothermal, hydraulic or nuclear, among others. Energy is a physical quantity that is displayed in multiple manifestations. Defined as the ability to perform work and related to heat (energy transfer), is perceived primarily in the form of kinetic energy, associated with movement, and potential, which depends only on the position or state of the system involved. Kinetic energy is an expression of the fact that an object in motion can perform work on whatever it hits; quantifies the amount of work that the object could perform as a result of its movement.

Kinetic energy

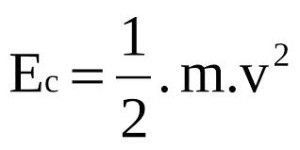

It is movement energy The kinetic energy of an object is the energy it possesses as a consequence of its movement. The kinetic energy of a point of mass m, where energy could be said to be everywhere and those bodies are constantly producing this type of energy in their displacement.

For a body to acquire kinetic energy or movement; that is, to put it in motion, it is necessary to apply a force. The longer this force is acting, the greater the speed of the body and, therefore, its kinetic energy will also be greater.

History of kinetic energy

The origin of the kinetic adjective comes from the Greek word kinesis, which means movement. The dichotomy between kinetic energy and potential energy goes back to Aristotle's concepts of actuality and potentiality.

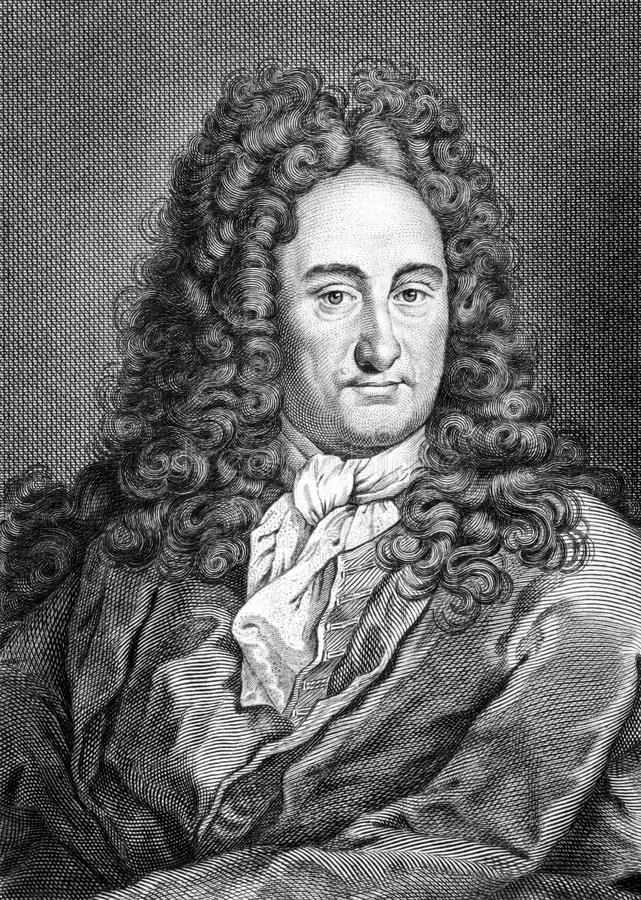

The first relationship between mass and velocity energy in classical mechanics was developed by Gottfried Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli, who described kinetic energy as living force. Later, Gravesande de Willem of the Netherlands provided experimental evidence of this relationship. When falling weights from different heights in a block of clay, Gravesande de Willem determined that his penetration depth was proportional to the square of his impact velocity. Émilie du Châtelet acknowledged the implications of the experiment and published an explanation.

The terms kinetic energy and work in their current scientific meanings date back to the mid-nineteenth century. The first to understand these were Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis, who in 1829 published the article entitled Du Calcul de l'Effet des Machines in which the mathematics of kinetic energy is sketched. William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, is credited with coining the term "kinetic energy".

Work in physics

Work is defined in physics as the force that is applied on a body to move it from one point to another. When force is applied, potential energy is released and transferred to that body and a resistance is overcome. For example, lifting a ball from the ground involves doing a job because force is applied to an object, it moves from one point to another and the object undergoes a modification through movement. Therefore, in physics you, can only speak of work when there is a force that when applied to a body allows it to move towards the direction of force.

This definition can be expressed mathematically by the following expression.

Starting from the formula, work is the product of the multiplication of force by the distance and by the cosine of the angle that results between the direction of the force and the direction that the object moves. However, work (null work) may not be performed when an object is lifted or held for a long time without a displacement being performed as such. For example, when a briefcase is lifted horizontally, since the angle formed between the force and the displacement is 90 ° and cos 90 ° = 0.

Neither created nor destroyed

We have all heard that energy is neither created nor destroyed, only transformed. It means the following: when one object causes a change to another, it obviously has to spend some of its energy. But that energy stays in another object, often in the same object on which the change has been caused. Let's see an example, of course related to the automotive industry. When we step on the accelerator, the fuel (thanks to all the processes that occur in the engine) uses its chemical energy to produce a change in the speed of the vehicle (apart from other secondary changes, such as producing noise, raising the temperature and moving the air). Now, as the car is moving, it has acquired kinetic energy, which can be used to produce other changes. And since we now have kinetic energy, we can produce changes. And the greater the speed, the more changes we can produce. What changes? For example, if we suffer an accident, all that kinetic energy can be used to deform and break both the vehicle and its occupants. Unfortunately, humans are not very resistant to deformations and ruptures. They are harmful changes and the more kinetic energy the vehicle has, the worse the changes that can be produced on us.

Hey, @martinezkarla , You copied the History of kinetic energy part from HERE. This is an intentional plagiarism. Also, the Images used are not Free. Please refrain from copying other's work and only use the images which are labelled as Free for reuse.

Hi, thank you for commenting on the truth, I am not committing any plagiarism this publication had already published it 3 months here ago and I just wanted to know what would happen if I republished it, at that time they did not have the copyright rule of the images but thanks for the warning. regards, @anevolvedmonkey

Just because you didn't get caught last time makes it okay now! That's not how copyright works!

How does that newtonian equation work when we take more modern versions of physics into our considerations?

Classical mechanics is just an approximation of Quantum mechanics, there is the Ehrenfest theorem that arrives at Newton's second law using Schrödinger equation. When we assume Planck's constant to be zero, we get Newton's second law. Learned this in the Freshman year but can't remember the exact math behind Ehrenfest theorem. ;)

Thanks for the breakdown mate!