Film Article: In the Shadow of a Terminator

Both The Terminator (Cameron, 1984) and its sequel Terminator 2: Judgement Day (Cameron, 1991) provide a protracted view of technological change. Whilst they respectively reveal the consequence of our increasing reliance on technology of the future, this article seeks to locate these films within a different discourse of fear. The human body begins to merge with machine through rapidly shifting military technology and combat, which ultimately produces a conflict between the dichotomised body and soul. This allows for an analysis of both films’ protagonist Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) as a cyborg soldier that undergoes an immense internal conflict. She is the site for pessimism of a future punctuated by mechanistic functioning as well as a site for optimistic hope for the continuity of humanism. This article also provides an examination of the way that consumerist technology, presented in both films, is shaping our future. Rather than providing a social utopia within a post industrialised society that had been anticipated by Karl Marx, the reverse is vast emerging, which is eroding the individual.

The Terminator articulates concerns over the ontogenesis of the human within a postmodernist society. The rapidity of technological change is frequently depicted through the juxtaposition of primitive and advanced technology throughout the film and the pervasive militaristic associations seem to permeate, providing a prescient allegory of our destructive future. This is visualised through the T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger). In a scene that draws on slasher film convention, we are offered a glimpse of the T-800’s point of view. An infrared visual display with crosshair is depicted and calibrates as it tracks its target Sarah Connor. Until this moment, the T-800 is aesthetically as human as the protagonists but these shots render him an artificial consciousness that is entirely militarised. For Forest Pyle these shots arguably suggest that the T-800 does not perceive by sight, rather he collects information (Pyle, 1993:232). In this sense, the film provides a startling vision of the coalescence of future warfare and image technologies such as the television and how these will mediate the experience of war. In their essay on the televised Gulf War, Kevin Robins and Les Levidow observe

'The Gulf video images gave us closer visual proximity between weapon and target, but at the same time greater psychological distance. The missile-nose view of the target simulated a super-real closeness which no human being could ever attain. This remote-intimate viewing extended the moral detachment that characterized earlier military technologies (Robins and Levidow 1995:120).'

The image that they use to illustrate this point is remarkably similar to the T-800’s mechanised point of view in the film. As American military technologies have advanced in the latter part of the 20th and early 21st Century, combat has progressively become more detached. Contrary to the close proximity combat that underscored earlier wars, the emerging ‘tele-engaged’ (ibid) war has begun to appropriate killing of the demonised Other on a large scale but with greater distance. As the Gulf War and subsequent wars have demonstrated, the human machine integration is leading toward the sanitisation of war and the symbolised loss of self. The T-800 in The Terminator therefore becomes a grotesque symbol of human evolution, the collision of technology and organism. In the same way that the combatant is desensitised and automatic, the T-800 is displayed in a similar fashion. This arguably suggests that the human of the future, ceases to be exactly that through physical and emotional hardening.

Previous wars have led to the automatized soldier and this is something that Chris Hables Gray has commented on. He observes that the ‘disciplining of individual soldiers into cleanly working parts, and the military’s fostering of industrialization and automation’ (Gray, 2002:56) ultimately situates the origin of the human-machine integration as being set within World War II (2002:56). The T-800 embodies this notion of the highly advanced and pre-programmed soldier. There is allusion to this when Kyle Reece (Michael Biehn) and Sarah Connor initially flee the T-800 in a commandeered vehicle. Reece describes the T-800 as an “infiltration unit, part man, part machine. Underneath it is a hyper alloy chassis: fully armoured, very tough but outside it is living human tissue, flesh, skin, hair, blood. Grown for the cyborgs” (1984). As is consistent with modern and indeed future warfare, this dystopian image of the unthinking soldier has become a reality. He is no longer impeded by logic, reason or emotion, he is the ultimate weapon. He is, according to Donna Haraway ‘the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism’ (Haraway, 2000:51). During a visceral scene that lingers on the T-800’s surgical extraction of his human eye, it is a moment that allows the cyborg to metamorphose into a pure machine; an image that is also echoed later in the film. Janice Rushing and Thomas Frentz consider this moment important as it suggests that the machine can function more optimally without the ‘human trapping’ (Frentz and Rushing, 1995:169). The eyes are widely regarded as the windows to the soul but in this scenario they are merely impractical tools that serve no means other than to promote inconspicuousness for the machine. As the T-800 reveals its mechanical red eye it provides a chilling metaphor for our future selves, one that effaces human agency. This moment reveals that this “second order simulation” (1995:168) is utterly efficient and no longer requires our surrogacy. The T-800 in the first film can be read as an uncanny variation of Frankenstein’s monster. The monster, who laments to his creator “I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from no joy for no misdeed” (Shelley, 1994:96) shows a very human depth and range of emotion; including compassion, empathy and wrath, therefore retaining his human elements. The T-800 does not question his existence like Frankenstein’s monster. This “new order of intelligence” (1984) as Reece describes it, has a sole function, one that is pre-programmed and soul-less. He is our machine ‘double’ (1985:356), a Freudian figure that is visually referenced in the sequel when the T-1000 (Robert Patrick) copies prison-guard Lewis’ (Don Stanton) body. This double is no longer a benevolent figure of immortality, he has become, as Freud observes, an ‘uncanny harbinger of death’ (1985:357); he is our telos. In his meditations Renè Descartes suggests that there is a duality between the body and the soul. He states

'I possess a distinct idea of body, inasmuch as it is only an extended and unthinking thing, it is certain that this I [that is to say, my soul by which I am what I am], is entirely and absolutely distinct from my body, and can exist without it.' (Descartes, 1911:28 emphasis in original)

Both the T-800 and the amorphous T-1000 – our future selves – have also become our Other and their organic structure conceals a void. They are, as Robins and Levidow argue ‘unadulterated efficiency-mentality without a soul, the part that, separated from the whole, is […] diabolical’ (1995:168). While the malevolent terminators of both films signify a humanist detachment from the more efficient machine double, both films explore present conflict surrounding the human cyborg body.

The cyborg body is presented in a way that verbalises a conservative disintegration of the family and the individual within both films. Sarah Connor’s body is the primary site for this fear. As systems become more mechanized, so does the human soldier. Whilst she goes through a transformative process from the first film to the second, Sarah remains subsumed into patriarchy. In The Terminator Sarah spends much of her time in a helpless position, conforming to what Bryan Turner describes as the psychic structure allocated to women in science fiction films – ‘affection’ (Turner, 1996:126) and ‘emotions’ (ibid); seeking protection within a male dominated society. In The Terminator, whilst experiencing a moment of respite, Sarah automatically dresses Kyle’s wound. Subsequently Kyle teaches Sarah how to make ammunitions. These of course will become crucial skills for her role however, this moment serves to alter Sarah both physically and psychologically. Samantha Holland has rejected James Cameron’s claim that both films are thematically feminist. She argues that while Sarah ultimately becomes a soldier, she can only achieve this by the instruction of her male counterpart (Holland, 1996:166) and by the momentary negation of her figure as a mother.

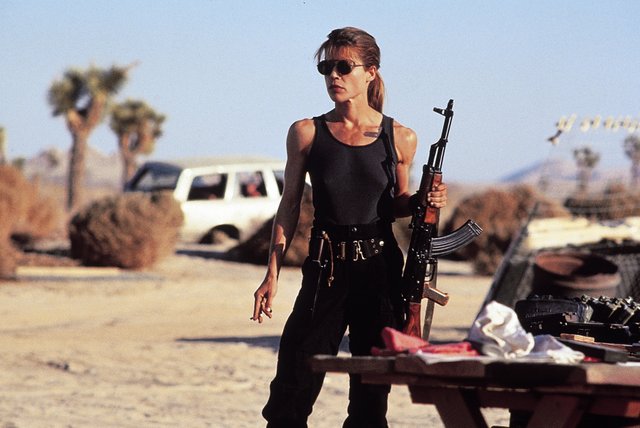

As Sarah becomes more mechanized by becoming highly weaponised, her gender becomes more fluid, however this has consequences for her maternal role. In Terminator 2: Judgement Day, she is visibly detached from John for much of the film. This reaches a crescendo as she emerges from a parked trailer. The camera lingers on her militarised body and the soundtrack echoes this with a steady military style drumbeat. Aside from her exposition at the beginning of the film where she has arranged her bed into a position that allows her to perform a number of upper body exercises, this is arguably her most masculinised moment. She rebuffs John and hastily drives away, thus rejecting her femininity and maternal nature. Gray explores the qualities of the cyborg soldier and argues that ‘the female soldier’s identity is collapsed into the basic solider persona, a creature that is vaguely male in dress and posture, vaguely female in status, and vaguely masculine-mechanical in role and image’ (2002:58). This is certainly evident of Sarah Connor in this film. This image is repeated, although in a somewhat hyperbolic style in James Cameron’s earlier film Aliens (Cameron, 1986) through the character of Private Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein). Vasquez is overtly coded as a masculine bodybuilder, with her male comrades being depicted as distinctly inferior. Her weapon – evidently an exaggerated phallic symbol – is almost as large as she. Holland has noted that this type of cyborg figure often de-stabilises gender identity (1996:166). She is deprived of any feminine qualities, in the same way that Sarah is in the scene above. She is wholly mechanical. This is emphasised further when she furtively stalks Miles Dyson (Joe Morton) at his house and places the reticule of her gun onto his head; a scene that is mirrored in the first film but with the T-800 adopting the same role. This is an overt reversal of meaning because the ‘shadow’ that is the Terminator, more specifically the T-800 from the first film and the T-1000 from the sequel along with Sarah Connor, are merging. Rushing and Frentz argue that ‘Sarah must unconsciously identify with the overdeveloped shadow before she can consciously recognize it as part of herself’ (1995:189). This recognition suggests that the emerging similarities between Sarah as a militarised hunter and the T-800 cyborg situate our pre-determined fate as beginning to emerge. At this moment in the film Sarah duplicates Kyle’s cold detachment from The Terminator when he callously remarks “pain can be controlled, you just disconnect it” (1984). This emergent cyborg soldier, Robins and Levidow propose, is trained for optimal efficiency. This includes the mastering of biological functions (1995:120). Sarah assumes this role until she is overcome by pity and empathy, thus allowing her to retain her humanity and ultimately to restore, as the narrative suggests, her passivity. This serves to highlight the polarised body and soul opposition that the cyborg has come to signify. The scene is therefore crucial to understanding the film’s pessimism surrounding technological advancement. The cyborg can only exist if the soul is disavowed. As Claudia Springer concludes ‘the cyborg represents the triumph of the intellect, it also signifies obsolescence for human beings’ (Springer, 1996:19).

This pervasive pessimism for technology is explored further through the blending of the individual with postmodern technology. Terminator 2: Judgement Day confuses the boundary between reality and simulation by juxtaposing diegetic combat with video games. When John Connor (Edward Furlong) is located at the Galleria shopping mall he, along with many other children are playing video games. More specifically however, John is playing a simple military game that resembles the T-800’s tracking point of view in the first film. Shown through degrees of primitiveness, he is later depicted as frivolously enjoying a far more complex game that allows him to simulate battle in a more physical way. As a reflection of the televised Gulf War images, Robins and Levidov have argued that

The images evoked audience familiarity with video games, thus offering a vicarious real-time participation. Video games in the wider culture are also about the mastery of anxiety and the mobilization of omnipotence phantasies; these psychic dimensions correspond to the cyborg logic of the military “game”. (1995:122)

What this suggests is that there is a comforting distance between the killer and the victim, a notion that transcends the video game. This scene is presented in a way that depicts technology through stages, evolutionary if you will. The vicarious nature of the evolving video game creates greater distance for the player. Haraway points out that ‘we are all chimeras theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism, in short, we are cyborgs. The cyborg is our ontology; it gives us our politics. The cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality’ (Haraway, 2000:50). Through the T-800 then we can see the culmination of advanced capitalism and subjugation. It is a truly dystopic vision of our evolution, which amounts to the reification of the individual and the inevitable split between the soul and the body.

This technophobia extends to the way modern technology and consumerism is presented in both The Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgement Day. Consumerist technology is frequently alluded to as either failing us or alienating us. In The Terminator a short sequence observes through close-up as Ginger Ventura (Bess Mota) and Matt Buchanan (Rick Rossovich) have sex and the camera’s eye lingers on the couple, not to arouse titillation within the audience but to highlight the emerging relationship we have to technology. Rather than experiencing the intimacy related to such an act, the couple are wholly detached. Ginger is fully engrossed in the music she is listening to through her headphones and pocket sized stereo and Matt proceeds to increase the volume for her pleasure. While Ginger and Matt fetishize technology in this way, they reveal an increasing alienation from one another and the negation of human interaction, thus creating a lack of individualism. This notion has more recently been expressed by subversive graffiti artist Banksy, through a mural depicting the same level of detachment.

Whilst written within the context of Nazi occupation, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s magnum opus the Dialectic of Enlightenment is a crucial text for deconstructing contemporary culture. They say that ‘the unity of the manipulated collective consists in the negation of each individual: for individuality makes a mockery of the kind of society which would turn all individuals to the one collectivity’ (Adorno and Horkeheimer, 1944:13). Therefore, if the individual is negated, then they become more susceptible to subjugation. Both The Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgement Day’s narratives draw attention to our relationship with technology and articulate an emerging subjugation by technology. In the second film an exasperated Janelle Voight (Jenette Goldstein) struggles to gain the attention of her apathetic husband Todd Voight (Xander Berkeley). As the camera follows Janelle through the house, it rests in the living room where Todd is unresponsive and absorbed in a sports game on the television. Noam Chomsky believes that televised and participatory sport is a form of indoctrination that reduces the capacity to think (Achbar and Wintonick, 1992). This scene then supports the argument that both films are presented as expressing fear of technological change. The scene is mirrored in the first film however, the meaning is reversed. Contrary to it being a vessel for inertia, in the dystopic future it has become a container for a fire that provides momentary warmth for two disconsolate children. As is demonstrated, technological changes have taken place between the two films. The Terminator shows Kyle running through a single department store in order to elude the police. In the second film a similar scene has been replaced with a large shopping mall, a fitting symbol of mass consumption and conformity. This conformity is echoed in the sequel when the T-800 (Arnold schwarzenegger) explains “my CPU is a neural net processor, a learning computer but Skynet pre-sets the switch to read only” (1991), to which Sarah responds “doesn’t want you to do much thinking huh?!” (1991). From Frederic Jameson’s perspective, we are living in an age where ‘the old individual or individualist subject is ‘dead” (Jameson, 1991:17). Similarly, Herbert Marcuse pondered this very notion. Reflecting on Karl Marx’ ideas, Marcuse states that reason would lead to the presupposition that technological advancement within an advanced industrial civilisation would exert greater freedom for the individual (Marcuse, 1964:14). Marx then viewed technology within utopian terms, suggesting that it would emancipate the human (Hughes, 2004:127) however, as has been argued by many of his successors including Marcuse, the technology of advanced capitalism, including its by-product consumerism, has developed a false sense of emancipation. Contemporary society has become ‘totalitarian’ (1964:14).

Whilst both films market themselves as revealing anxiety surrounding future technology as becoming self-aware, they implicitly express a far more unnerving fear. Fundamentally our military technologies are providing greater psychological distance between killer and victim and video games provide a comparative mediation. By looking at a target on a screen the emerging cyborg soldier need only press a button to cause human destruction. The soldier becomes increasingly weaponised as well as physically and emotionally conditioned. This produces a more efficient killing machine, which will ultimately renounce the self. Explored further through the character of Sarah Connor – a soldier in transition – she serves to remind us that this fragmentation is a very present threat. She oscillates between mimicking the T-800 in her mechanistic functioning and her very human, maternal nature. Ultimately she opts to retain her humanity so that the human-machine may at this point remain separated. A further commentary is made on technological advancement as alienating us and disintegrating the individual. In the six years between each film, products and devices have developed exponentially, thus providing the Galleria shopping mall as a useful image to illustrate this notion. Indeed, as Adorno and Horkheimer deplore ‘the fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant’ (1944:3). Technology then has not liberated us, it has only led to greater confinement. It is however, worth remembering Kyle Reece’s enduring phrase, which Sarah eventually adopts - “there is no fate but what we make for ourselves” (1984, 1991). The hope is that we are not destined to become the shadow of the Terminator.

If you find any of my articles or reviews of interest please follow me and UPVOTE. Thank you for taking the time to read my article.

Bibliography has been removed for the purposes of copyright

Copyright 2015 Rebecca Cohen

Congratulations @filmscholar1981! You have received a personal award!

Click on the badge to view your Board of Honor.

Congratulations @filmscholar1981! You received a personal award!

Click here to view your Board

Congratulations @filmscholar1981! You received a personal award!

You can view your badges on your Steem Board and compare to others on the Steem Ranking

Vote for @Steemitboard as a witness to get one more award and increased upvotes!