Pioneers Of Astronomy: Robert Hooke

PIONEERS OF ASTRONOMY: ROBERT HOOKE

(Image from wikimedia)

Robert Hooke is an important figure for a couple of reasons. Firstly, he was a far-sighted individual whose wide-ranging contributions to science put him on equal standing with Sir Isaac Newton, at least to the unbiased historian. Secondly, his is a story that shows history is not unbiased and it is a sad fact that there are many unsung heroes of science; people who (for one reason or another) did not gain the recognition they deserved. Hooke’s mistake was to upset Newton, whose response was to re-write history so effectively that only in recent decades has the former scientist’s contributions been recognised.

EARLY LIFE

Robert Hooke’s life was a struggle from the very beginning. He was born seven years after Galileo died, on 18th July 1635. He was the last of three children, the other two being Katherine (1628) and John (1630). Their father, also called John, was the Curate at All Saints Church at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. This was not a well-paid position and the family was far from wealthy. Robert Hooke suffered various ailments as a baby, and these were bad enough to make his survival doubtful. For this reason, he was not provided with an education. But when it seemed he might survive after all, his father took up the task of teaching his son, giving him a rudimentary education that was enough to prepare him for a role in the church. These ‘classes’ were an intermittent affair: Hooke’s continuing ill health and his father’s increasing frailty ensured he was left to his own devices for much of the time.

Despite his condition, the young Hooke had an active boyhood. He enjoyed running and jumping, but his real passion was model-making. This was an area in which he demonstrated great proficiency. Among the things he built was a working wooden clock, constructed after he saw a brass one taken apart. His hobby required him to spend hours hunched over his tools. when, at the age of sixteen, he developed a pronounced malformation of the body, he attributed it to the amount of time he spent at the lathe. As well as a skilled model maker, Hooke was also a dab hand with the brush. He first discovered he had this knack when an artist visited Freshwater. Watching this person at work, Hooke decided to have a go at painting himself. He made his own paints and was soon producing copies of professional works with sufficient skill to suggest a possible career as a professional. When his father died in 1648, the thirteen-year-old Hooke inherited £100 and was sent to London to be an apprentice to an artist called Sir Peter Levy. Hooke never took up the position, firstly because he thought he could learn all he needed to know by himself, and secondly because the smell of paint gave him severe headaches. So, instead, Hooke used his inheritance to pay for an education at Westminster school, a place that counted Christopher Wren amongst its former pupils.

EDUCATION

At school, Hooke learned to play the organ and in 1653 he joined Oxford’s Christ Church College as a chorister. This, however, was no musical education because under Cromwell’s puritanical government choirs were considered indulgences to be done away with. For Hooke, this essentially meant that he received a scholarship for free, although he still had to work as a servant in order to make ends meet. Because of his skills with model making and experimenting, Hooke soon proved himself useful as a scientist’s assistant and many important experiments were made possible because of his input. One such example that is relevant to the current topic is that he produced improved telescope sights while working for the professor of astronomy, Seth Ward.

THE ROYAL SOCIETY

(Image from The Times)

Hooke never completed his studies because in 1662 he left Oxford in order to take up a job at the Royal Society. It was here that he made one of his lasting contributions to science, because it was largely his efforts that transformed the Royal from a mere talking shop into a scientific society that is the envy of the world. It was the founding of such societies that really marks the middle of the 17th century as the time when science became part of the establishment. Perhaps fittingly, the first such society to gain official sanction was established in Renaissance Italy. It was founded in 1657 by former pupils of Galileo named Evangelista Torricelli and Vincenzio Viviani. Also fittingly, this society (known as the Accademia del Cimento or Academy of Experiments) was closed in 1667, a date that roughly coincides with the time when Italy’s leadership in the physical sciences came to an end.

Around the same time, what would become the longest-lasting society began to meet in London. From 1645 onwards, people with an interest in science began to get together with the express purpose of discussing the emerging ideas of the day, also sending letters back and forth across Europe so that like-minded people there could contribute to this information flow. This gathering became the Royal Society in 1662 under charter of Charles II. The Royal Society soon realised that it needed two permanent members of staff- a secretary to look after administration and a curator of experiments. The first post was awarded to a German called Henry Oldenburg and Robert Hooke became curator of experiments. His job was to perform experiments at every weekly meeting, either of his own design or those suggested by other Fellows. Evidently, he threw himself heart and soul into this task because the minutes from the early years of the Royal are full of references to his work. As if that was not enough, he was also professor of geometry at Gresham College (from 1665 onwards) where he was required to give full courses of lectures.

Although Hooke never completed his studies at Oxford, by 1663 he was awarded his MA anyway and elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. This put him on equal standing with his fellow members, but in those early days the disorganised nature of the Royal meant it was often very low on funds. Hooke was kept financially afloat by Robert Boyle (whom he had assisted at Oxford and had recommended him for the post of curator). Another problem was that Hooke was so busy keeping the Royal running that he had no time to build on the success of a book he wrote called Micrographia.

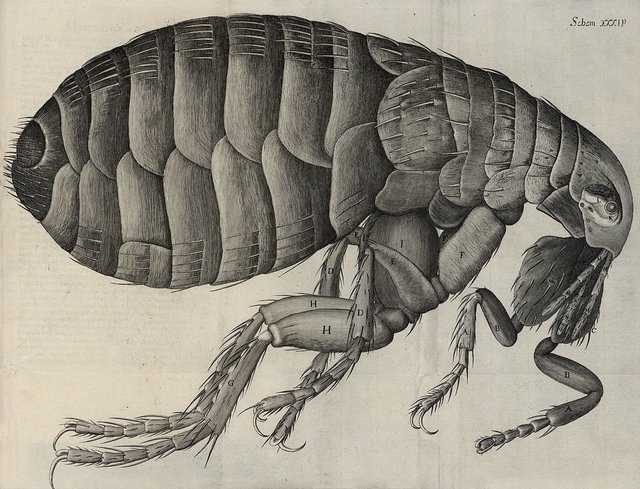

MICROGRAPHIA

(Image from Wikipedia)

As its name suggests, Micrographia was all about the study of microscopy and was the first substantial book on the subject. Today, the book is recognised as one of the most important ever written. It showed the hitherto unknown world of inner-space, a revelation every bit as profound as Galileo’s discoveries with the telescope. Hooke was not the inventor of this instrument (that was Galileo) and he was not the first microscopist, but his book marks the moment when this scientific discipline came of age. We won’t linger on the book for too long because it is not really relevant to the current subject. It is worth skimming through some of Hooke’s discoveries, though, to give an idea just how wide-ranging he was.

He correctly identified fossils as the remains of dead creatures, and was one of the first people to understand that great changes had affected the Earth over immense tracks of time. He came close to discovering oxygen one hundred years before its actual discovery and came remarkably close to a proper understanding of the causes of heat two hundred years ahead of his time. As well as inventing improved microscopes he also invented the familiar clock-face style barometer. Using this and other devices made with his own hand, he became the first meteorologist and saw the connection between changes in atmospheric pressure and changes in the weather. By studying the wings of butterflies, Hooke became entranced by the coloured patterns produced by thin layers of material and this inspired him to study the nature of light. His work, in turn, inspired Newton to do likewise and a phenomenon known today as ’Newton’s Rings’ were actually discovered by Hooke. That just shows how effective Newton was at rewriting history.

NEWTON’S ANTAGONISM

You might be wondering why Newton felt so antagonistic toward him. Well, for one thing, he felt that way about pretty much everybody. In 1666, inspired by Hooke’s own investigations, Newton embarked on a study of light. When he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, he presented a paper on light and colours, but downplayed the role that Hooke’s own investigations had played. Hooke, who had always been rather touchy when it came to giving and receiving due credit, let his dissatisfaction be known to his fellow members. As for Newton, he had a largely justified yet infuriatingly high opinion of himself and looked down on his fellow scientists, regardless of their seniority. So when Oldenburg (who had long taken a dislike to Hooke) passed on an exaggerated account of Hooke’s grumblings, Newton did as he hoped and formed quite a grudge. For the next four years these men did battle with each other, to the extent that it was feared they would make the Royal a laughing stock. It was decided that, whatever their private feelings might be, they should make a public reconciliation. This was achieved through a series of letters, and one that Newton sent contained a passage that has now become legend: If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.

‘Standing on the shoulders of Giants’: That is a neat appraisal of the true nature of scientific progress. Rarely revolutionary; more often incremental steps taken by one generation building on the work of those who came before. But while it may be a true account of the evolutionary nature of science, it hardly reflects Newton’s true self. Obviously he made his apologies under duress, but the phrase seems to be a bit too modest for a man famously lacking in such a virtue. Actually, the phrase may well have been a sly insult directed at Hooke, who was quite small in stature. As for Newton, he retreated into his shell at Cambridge and refused to make his work on light public. For thirty years he sat on it, only releasing it after his old rival had died in 1703, and could not comment on it or claim credit for any discovery.

There were other reasons why Hooke failed to build on the immense promise of his masterpiece. One problem was that he decided to write the book in English. Although this gave him a readership much wider than the scientific community, his style of writing made his work sound almost easy. Soon after it was published, plague swept through London, forcing Hooke and the other Fellows to leave the capital and seek shelter in the country. Proceedings were interrupted again in September 1666 when the Great Fire of London saw Hooke’s scientific investigations halted for years. He certainly wasn’t idle during this time, though. In fact, apart from Christopher Wren (who was a good friend and produced some of the illustrations in Micrographia) Hooke was the principle figure behind the rebuilding of the city and many buildings credited to Wren also benefited from Hooke’s expertise. This fits in nicely with the image of him as a kind of unsung hero, but 1666 was also important because it marks the year in which Hooke read a paper on planetary motion. As we shall see, this would be the beginning of another argument between him and Newton. This time, though, the end result would see the latter scientist come out of hiding with the most important book in the history of science…

REFERENCES:

Science: A History by John Gribbin

Newton by James Gleick

Wikipedia entries on Newton, Hooke, and Halley