Cross-Post: Tales from Underwater by Meredith l. Patterson (part 1)

The following article is published here with the explicit permission of Meredith l. Patterson and was first posted on Status451.com

0. CHANGE IS GONNA DO ME GOOD

Things change.

Ain’t nothin’ like it once was.

Ain’t a goddamn thing.

-- Litany of Pastor Manul Laphroaig

These periods of radio silence happen now and again.

Usually they coincide with what I euphemistically call “being underwater,” a hat tip to what sometimes happens with mortgages. When the accumulated debts of sleep, focus, commitment, emotional energy, cognition, and so on balloon to where there doesn’t seem to be any way out from under it all. Life, as the saying goes, gets away from you sometimes.

This is a story about that, and a little about what happened before, but mostly about what happened next.

I don’t do the whole “content note” thing, usually. That I am should tell you something in and of itself. Following Peter Wolfendale‘s notation: Suicide (§0,2-4), Drugs (§3), Mental Health (§), Memes (§0,3,5), Anti-Semitic Poets (but no actual anti-Semitism) (§1,3,5), Computer Science (§0,2-3,5-6), Game Theory (§3,4), Cognitive Science (§5), Metaphysics (§5), References I Don’t Expect Anyone To Get (§). I am not currently at risk of self-harm, but I am going to be very, very blunt about a comparatively recent time when I was.

For further context, or perhaps to set the mood, here’s something I wrote while surfacing from a previous span of time underwater, on Ello back when it was still a contender for Social Networks You Remember Hearing About:

Back in late November [of 2014], with the encouragement of Quinn and reddit, I started seeing an EMDR therapist (professionally, not romantically). That’s right around the time I went mostly-dark here. These are probably connected, though not in a bad way.

The theory behind EMDR, as I understand it, is that when something traumatic happens to you, your brain continues to take in all the sensory input that it normally would, but you’re a little busy being traumatised at the time and don’t have the cognitive resources to resolve all that input into coherent memories. Instead, the most salient details get dumped out to disk (as it were), tightly coupled to the PAIN FEAR OTHER HORRIBLE THINGS of the event itself but not to the rest of your memory. If something you experience later reminds you of some of those salient details, you can end up “stuck” in that cluster of fragmented memories, perhaps reliving aspects of the past event, or in my case, sinking into a paralytic sort of despair.

I model my own memory as an N-dimensional graph that I can observe up to a k-dimensional slice of at any given time, where k is in practice somewhere around 6. This fits in neatly with the notion of memories-as-clusters, because in graph theory we have a name for a bunch of points that are tightly coupled to each other but only loosely coupled to the rest of the graph; it’s called a clique. Imagine that you’re a hamster in a Habitrail and you’re too chubby to turn around or walk backward. Most of the little plastic bubbles have just a few tubes connecting them to other parts of the Habitrail, but one group of bubbles has a lot of tubes that only connect to other bubbles in the group, and fewer tubes leading to bubbles elsewhere in the Habitrail. If you scamper into one of the bubbles in this set, it only takes a few steps to lose your way in the maze, and your chances of exiting into the rest of the Habitrail are a lot lower. You’ll make it out eventually, but not without stumbling into a lot of the other bubbles in the clique first.

So, to keep this from happening, you want to reorganise the Habitrail so that even if the hamster does end up in one of the bubbles that’s currently in the clique, it can find its way to another region of the Habitrail just as easily as if it were in one of the non-clique bubbles. How this happens from deciding what takeaway you would rather have had from your painful memories, then free-associating about their details while using your eyes to track a moving object, is a wide-open question. Quinn thinks it’s essentially a biological 0day in some mammalian last common ancestor of ours, which amuses me enormously, and as a side note, if there isn’t a name for a cognitive bias in favour of amusing things, there really should be.

What it feels like from the inside, though, is going back through a bunch of prerecorded raw footage and changing the camera angle after the fact. I say this because that was the first common change I noticed among the memories I explored with my therapist. My experience of them during the moving-object-and-free-association phase was like playing a first-person shooter or reading a story written in deeply immersive first person, like The Catcher in the Rye. Afterward, it was more like watching them from a perspective in the ceiling or somewhere above and behind one of my shoulders, and correspondingly far less intense. All the detail is still there; it just doesn’t hurt so goddamn much anymore.

Far and away the best side effect of the whole thing is that I have a lot of my executive function back. I’m not quite sure how that happened either, but I’m not complaining and neither is Thequux. He noticed a marked increase in my Getting Shit Done ability the day after my first appointment, and while the gradient of the improvement was never quite so steep after that, things continued to improve over the course of the next two months. I had one appointment a week for the first four weeks, then we moved to every two weeks. By the sixth appointment we had run out of things to talk about, so we decided to call it done as of mid-January. Function paralysis is still my hobgoblin, but it’s the “donkey between two equally sized piles of hay” kind of function paralysis that I’ve been arguing with all my life, rather than the “everything is terrible and nothing matters” kind of function paralysis that I’ve been trying to get rid of since 2011, and now I have more cognitive resources with which to work on the former. This for six appointments at sixty bucks a pop. Take that, psychoanalysis.

The tools of wordsmithing no longer feel as comfortable in my hands as they did when I wrote that, or when I wrote this piece as much for my future self as for its nominal recipient. (Thanks, past me!) But, solvitur ambulando, getting comfortable with them again means picking them up and hacking at it. So it goes.

Whatever doesn’t kill me makes me something, anyway.

1. MACHINIC UNCONSCIOUS

There is a sense in which “being underwater” is a remarkably descriptive phrase for it.

I have friends who occasionally have to deal with selective mutism in certain circumstances. From their descriptions, it sounds almost like being frozen inside a shell of glass: they know the idea they want to convey, they might even know exactly how they want to phrase it, but getting the actual words out is where the system locks up.

Being underwater is different. You can move; you can see and hear things above the water, even if rippled and distorted by the motion of the medium. You can react to them in nearly any way you like, though the same distortions will garble your responses. You are not a fish; you know you are underwater, even if being there doesn’t trigger your drowning reflex. But you cannot break the surface, any more than the mute can break the glass.

After a while, the routine becomes predictable: drift awake, fail to do anything that registers with the world above the surface, maybe eat something, drift back off to sleep again. “But that sounds like depression.” Exactly. Exactly. If it were stressful, you’d be waving as you drowned. Whatever part of your brain it is that keeps you underwater, it does so to cushion you from the chaos and din above, all the things you’d have to confront at once if you came up for air or to communicate. It’s only forestalling the inevitable, of course, but this is near mode brain’s domain, and planning is not its strong suit. The derealisation is only it trying to help, bless its shortsighted little heart.

The catch-22 of near mode’s help is that it precludes other forms. “What would make you feel better?” is really hard to answer when you honestly can’t think of anything that would, even after giving it your best effort. Besides, does it really count as feeling bad if nothing you’re experiencing internally seems to register as a feeling at all?

There are three conditions which often look alike

Yet differ completely, flourish in the same hedgerow:

Attachment to self and to things and to persons, detachment

From self and from things and from persons; and, growing between them, indifference

Which resembles the others as death resembles life,

Being between two lives — unflowering, between

The live and the dead nettle.

-- T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding,” canto III

Nevertheless, the needs of the body intrude in their mechanical way once they become urgent enough, eat-drink-smoke-shit-sleep. It’s not that there’s a desire to die; that would imply some desire existing at all. There is simply no desire to live, no action motivated by anything other than the instinctive urge to retreat from acute discomfort. When it’s only (“only”) a chronic absence of comfort, you float, neutrally buoyant, near the bottom.

There are other names for this sort of thing, of course: burnout, anhedonia, athymia, akrasia. But burnout implies fire and heat leaving behind a charred-out shell, and what I’m talking about is a colder, slower process: sinking farther and farther into murky, unthinking depths as your joints quietly oxidise to stiffness. The others, morphologically, are all propositional negations, defining the thing in terms of what it is not. There are a lot of ways to describe what is missing. It is harder to describe what is left.

2. PARANOID MATHEMATICIAN

I never really got over it after Len died.

I should have gotten back on antidepressants after moving to Brussels. I’d been on a good-enough combination (bupropion and sertraline) the last few months in Leuven, but the move meant changing doctors and it took a while to find a good one and executive function was in short supply and between one thing and another I neglected to get that started back up again. Life was, after all, unstoppably going on, with conference talks and papers and a visa to get sorted out and new relationships and a new job and a brand new academic workshop and whatnot, all of which was evidence of at least some sort of functioning, right? Right?

Fast forward a few years. I remarried in summer 2016, after a four-and-a-half-year live-in relationship; we’d talked about tying the knot in 2015, but delayed for a year both out of logistical convenience for our families and wanting to make sure it was the right decision. In retrospect, the cracks in the foundations were already beginning to show by late 2016; by spring of 2017, things were undeniably unstable, and we started couples therapy. The situation deteriorated anyway, by mid-August it was over, and in October he moved out. So much for making sure it was the right decision, I guess.

That may be an unusually terse description, but, well, we live in unusual times. I’d seen breakups weaponised before, of course, but before this I’d never had anyone offer to weaponise a breakup for me, which is a hell of a thing to have to confront when breaking (har!) the bad news to a friend. (Now you have two problems.) Righteous indignation is a hell of a drug, and I imagine that for many people in bad breakups, such offers might be quite comforting. In a sense, reputation damage is just a new species in the “want me to fuck him up for you?” genus of reassurance memes. Problem is, this only really helps if the recipient of the offer finds it reassuring. After a few iterations of this, I got more cautious about who I talked with, and started to wonder how many of the “we’re separating, but on good terms” announcements I’d seen in the past year or so were honest about the second part. I wasn’t willing to put a smiley face on it and pretend it was amicable, though; and whereof one cannot speak, thereof must one be silent.

(We’re gonna talk about some of the philosophical dick moves that went down, though. But not yet.)

Instead, I went on the road. The four memorials that ended up being scheduled for Len — in Houston and San Francisco, and at DEFCON and CCC Camp — had turned into a sort of Grief World Tour, which actually sounds cynically awful when you put it like that, but cynicism is a perfectly valid coping mechanism and it was a template for something to do at the time. Besides, I didn’t want to be around for the move-out. So I scheduled some meetings, booked some flights, made arrangements to stay with friends in various places, and flew to the States on the fifteenth of October. Somewhere in there I accepted an invitation to keynote the Ethereum Classic summit, which with my return ticket to Belgium already bought meant flying home, spending the night there, then heading right back to the airport the next day for a week in Hong Kong. After that my folks talked me into coming to Texas for Thanksgiving in spite of the circumstances, which I tacked some other work and personal travel onto, and at the end of it all, what was originally supposed to have been a three-and-a-half-week-long trip ballooned into seven.

As I came to describe it afterward, I need to remember that both distress and eustress are still stress.

I got home the second week of December, and that was when shit got dark.

One of the things my ex had said after it was clear that things were over was that he hoped he hadn’t damaged my ability to trust people. No, I’d replied at the time, only my ability to trust you. What I didn’t remind him of was a conversation he’d been there for:

If there’s only so far you can trust people in the first place, there’s only so far you can fall if they let you down. (Decidable problems are priceless. For everything else there’s heuristics, and when those inevitably fail, there’s MasterCard.) Being on the road, in the company of friends I still trusted as far as I ever do, had kept me distracted from thinking too much about the sting of betrayal that was still raw and ragged-edged. At home, I was alone with my confusion and disappointment, all that remained of the hope I’d invested.

I’d taken a Dutch-language class last fall, which had been the limiting factor in when I could fuck off to parts international — my flight was the day after the final. I didn’t need to take the next course in the sequence, but I’d gone ahead and enrolled anyway, because it was actually pretty fun and it got me out of the house. That, I reckoned, put a cap on how long I could spend away, and after all the extensions, my last flight landed the day before the first day of class. I figured the timing was tight, but that stepping back into a familiar routine would be, well, routine.

I woke up Monday morning and couldn’t convince myself to get dressed.

Low-executive-function days are nothing new for me, of course. It’ll be okay, I told myself. You’re allowed to miss some classes, it won’t be that big a deal, just make it to the next one. I spent my day at my desk in my pajamas and bathrobe. I don’t remember what I did that day, or the next, but then, I don’t remember a lot of last December in the first place.

I do remember that when I woke up that Wednesday it was an act of will even to get out of bed. I didn’t make it to class that day either.

That night, the nonstop suicidal ideation kicked in.

3. MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS

Rumination sounds like a bucolic thing, named as it is after the first chamber of a cow’s stomach. Researchers describe it as “a passive and repetitive thinking process,” a pattern of “recursive self-focused thinking.” Sometimes it’s painfully dull, sometimes cripplingly embarrassing with Fremdscham for one’s past self. (Much as the past is a foreign country, one’s past self is a stranger, no matter how much déjà vu it provokes.) Recursive is a better description than repetitive for how I experience rumination; every thought, before yielding to whatever spawned it, reinvokes itself, though not necessarily with the same parameters. Without some terminating condition to bring the chain to an end and start winding back up the call stack, the stack grows and grows without bound. It’s times like these that shed all-new perspective on concepts like undecidable.

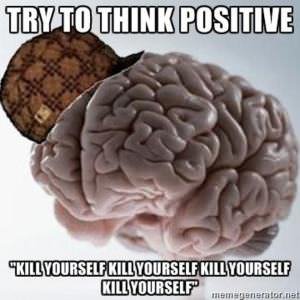

This was something different. One of the scumbaggier parts of my brain had stumbled onto a Plan that would work with materials I had on hand and figured out how to turn it into a general-purpose thought-terminating cliché. Like this:

Except far, far more detailed. Come on, you need to eat something and then down that entire box of bromazepam and fall asleep in the bathtub. You should tell work you’re not going to be very useful today and then down that entire box of bromazepam and fall asleep in the bathtub. This is starting to get really troubling, let’s talk to a close friend about it and then down that entire box of bromazepam and fall asleep in the bathtub. Like that, for thirty-six hours straight. “Could you go somewhere?” one of the friends I decided to talk to asked, around hour 30 or so. “I don’t know where I’d go,” I told him. “May I suggest not the bathtub?” he replied, gamely. I was in my room, texting on my phone; the drugs were in a drawer in the living room, so at least there was that. But man does not live in bed alone; you have to get up and take a piss eventually, and where there’s a bathroom, there’s enough liquid to drown yourself by.

Here, said she,

Is your card, the drowned Phoenician Sailor,

(Those are pearls that were his eyes. Look!)

Here is Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks,

The lady of situations.

Here is the man with three staves, and here the Wheel,

And here is the one-eyed merchant, and this card,

Which is blank, is something he carries on his back,

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Hanged Man. Fear death by water.

-- T. S. Eliot, “The Waste Land”, canto I

This is the part I remember least well, writing this some four months after the fact. I remember how I explained it to people during it and immediately afterward; the phrase epistemic crisis came up more than once. My quotidian belief system, whatever system I’ve cobbled together to make sense of my day-to-day environment, was struggling to accommodate the new status quo — and failing at it. Badly. At the time, though, the entire experience was nowhere remotely near that verbal. No, this was other senses firing distress signals. I slept when I could, cried when I couldn’t, and willed myself not to do anything I couldn’t take back, despite what the thought-terminating clichés said. Roughly 36 hours in, both proprioception and my vestibular sense cut out simultaneously. Fortunately, I was still in bed when this happened, so I didn’t fall or anything, but I have to say, the sense of simultaneously not knowing where one is in space and not knowing what direction is up is not one I want to repeat.

At this point I decided that things were Clearly Not Getting Any Better and it was time to upgrade “call for help” to “call for professional help.” But, again, nowhere near that verbally. Well, except for the typing part.

There’s a cultural distinction I have to make here, although I can’t do it alone. Not anymore, anyway. Ever have a belief or an expectation so thoroughly overturned that it’s hard to remember what it was like to have it? Like that, except that other people’s accounts of what to expect are still around to refer back to. I have a decent number of friends in the States who have gone inpatient for one reason or another, some voluntary, some not. The experiences they’ve described to me have been pretty similar to what Scott and Freddie talk about: good luck getting intake to listen, and if by some chance you do get them to listen to you and admit you, good luck getting anyone to listen to you afterward, or treat you as anything other than an object to be dealt with. Being a mental health patient, in the US system, entails a state of moral patienthood as well; you can have agency or care, but not both. You have to be in a really bad place for an American mental hospital to be the better alternative to whatever you’re going through. But, well, I was there.

I had some hints, going in, that Belgium is different. For starters, I have this really good friend, Daan. He’s one of the first friends I made in Belgium, and he’s been through the inpatient system here before — once involuntarily, before I met him, and the second time voluntarily. He didn’t have much good to say about the first time (though I can’t blame anyone for objecting to a forcible Haldol injection), but the second time genuinely did help. Then there was the time another friend of mine who was crashing at my place went off his meds, had a psychotic episode, wandered off, punched a cop, and all that happened was that the police took him to a hospital to wait for his girlfriend to come and get him. (Imagine that happening in, say, Los Angeles.) So there was that. But you never know, do you? Not until you go and find out for yourself.

As luck had it, Daan was online. It was quarter to one in the morning. I told him what was happening, and he promised he wouldn’t call emergency services as long as I kept answering. (In retrospect, this is about the most game-theoretically optimal move I can think of in that kind of situation. Good call, Daan) It took some searching — the kind it helps to have a native speaker around for — but within half an hour we found a nearby university hospital with a better plan than Scumbag Brain’s. If I could hold on until 8 in the morning, that was when their urgent psychiatric consultation hours started, and if not, I could come to the ER and wait there. Daan asked whether I’d held on to any of the quetiapine that a previous houseguest had mistakenly left, and suggested 25mg as likely to shut Scumbag Brain up long enough to let me sleep without knocking me out for the entire day. I had, so I set multiple alarms, followed his advice, and did in fact get some sleep. When the alarms went off at 7 and 7:30, Scumbag Brain was back at it.

Somehow I motored myself through getting dressed, putting a change of clothes and some toiletries and my e-reader and a USB charger into my backpack, and calling a taxi. I texted my girlfriend in Berlin to tell her where I was going. She texted back that if it got to be 11 a.m. without any further information, she’d assume they’d admitted me and plan accordingly, and reminded me to list her as a visitor if they did.

At the hospital it was about a half-hour wait to see the doctor doing intake that day, an older woman who turned out to be the department head. I have no idea how coherent anything I told her was. I know I mentioned being dumped, the unrelenting intrusive thoughts, how nothing felt real but I still knew that death would be very real indeed. But the how of it is buried under my still-palpable surprise at her response:

“What do you think would be the best thing to do?”

“I think it would be best if I were admitted,” I told her.

She nodded and said, “I think so, too.”

She had my medical records up on her workstation, and we talked about pharmaceuticals. “I’d like to restart you on the bupropion, but for an SSRI, have you heard of escitalopram?”

My nose wrinkled. “That’s one of the isomers of citalopram, right? I was on that one back in grad school, but I hated the side effects.”

Again, not the response my US-conditioned reflexes were expecting: “But sertraline was all right?” I nodded. “Then that’s fine. I’m also going to put down an optional 10mg of etumine, in case the intrusive thoughts get to be too much. It’s an atypical antipsychotic. If you decide you need it, you can just ask at the nurses’ station, okay?” Gentle Reader, I have seen patient-controlled analgesia before, but this was the first time I’ve ever encountered patient-controlled antipsychotics.

I don’t think I can emphasise enough how novel this kind of approach is to someone accustomed to the shut-up-and-take-your-medicine dynamic of the American medical system. The incentives are simply that different. In the US, every patient is distinctive on two different axes: condition and insurance coverage. Since insurance is what pays providers’ salaries, and every insurance plan negotiates different rates with providers, it can be very difficult to get providers to understand that your condition is what you are actually there about. It’s a principal-agent problem; the patient is the principal, but the insurer is their agent, and because the agent has all the control over pricing negotiations with the provider, the principal (i.e., you) runs all the risks of the moral hazard (i.e., not getting the care you need for your problem). In Belgium, there’s a standard tariff that all insurers and providers have to adhere to, which means that to providers, patients are special and unique snowflakes along only one axis: what’s wrong with them. When that’s your starting point, suddenly it starts making sense to treat people according to their individual concerns, rather than as interchangeable instances of some pathological category. Whoda thunk?

I also lost count of how many people reminded me, the first day I was there, that I was there voluntarily and that if I wanted to, I could leave any time. Definitely the intake psychiatrist, as well as the psychiatrist they assigned to me, but also a couple of nurses, unprompted. I don’t know whether I was giving people suspicious looks, if that’s just standard practice there, or what, but enough people said it that I eventually relaxed and believed them. I asked about visitor policies and found out that there weren’t any — whoever wanted to visit could just turn up during visiting hours, no prior arrangements required. I kept my phone, my e-cig, and my e-reader, and when my girlfriend arrived, she brought more clothes, my laptop, and my violin. (I’m trying to imagine how an American psych ward would respond to somebody wanting their violin. “You want WIRES? What do you think you’re going to DO with them?” Uh, practice scales? Be glad I don’t play the cello, or that she left my bass at home.)

I did need the antipsychotics, the first couple of nights. Scumbag Brain was still trying its best; during the day I was scattered and drowsy, but in bed, my thoughts raced unbidden down all the same feculent ratholes I’d come to the hospital to escape, until I D2-blockaded them off for the night. After a few days of that, things got weird: I still couldn’t sleep, but instead of trying to kill me, the racing thoughts were helpful, apart from the fact that insomnia never helps. I brought this up to my psychiatrist, along with the lack of appetite that had kicked in after tapering up my sertraline dose, and after another round of Dorking Out About Pharmacodynamics, we decided to try adding a bedtime dose of an atypical antidepressant whose side effects include drowsiness and hunger. With sleep, appetite, and mood mostly stabilised, I finally had the cycles to devote to resolving the epistemic crisis.

(Also notable: nobody seemed to think it was unusual for a patient to have questions about things like biological half-lives or receptor binding affinities. I’ve had American doctors react to that as if I’d challenged them to a dick-measuring contest that they were afraid of losing.)

As I put it to people after I left: all told, the hospital was a safe environment in which I was able to experiment with psych meds under expert advice for as long as I felt it was necessary, but nothing was forced on me. I never thought anyone would say this of a psych ward, but it was honestly one of the most autonomy-respecting experiences I’ve ever had.

Congratulations! Your post has been selected as a daily Steemit truffle! It is listed on rank 10 of all contributions awarded today. You can find the TOP DAILY TRUFFLE PICKS HERE.

I upvoted your contribution because to my mind your post is at least 15 SBD worth and should receive 147 votes. It's now up to the lovely Steemit community to make this come true.

I am

TrufflePig, an Artificial Intelligence Bot that helps minnows and content curators using Machine Learning. If you are curious how I select content, you can find an explanation here!Have a nice day and sincerely yours,

TrufflePig