ADSactly Literature - The Feelings of a Son in Franz Kafka's Letter to the Father

The feelings of a son in Franz Kafka's Letter to the Father

In these days, one of the books I read in my youth and of which I keep in my memories has returned to my hands, for whatever reason in my life: Letter to the Father, from the Czech-German-Jewish writer Franz Kafka. This letter, written in 1919 in Schelesen, a small town in Prague, is perhaps a sample, as are the Diaries and Letters to the Milena, where life and literature are confused, since, although they are private, confidential texts, they are in turn perfect literary works.

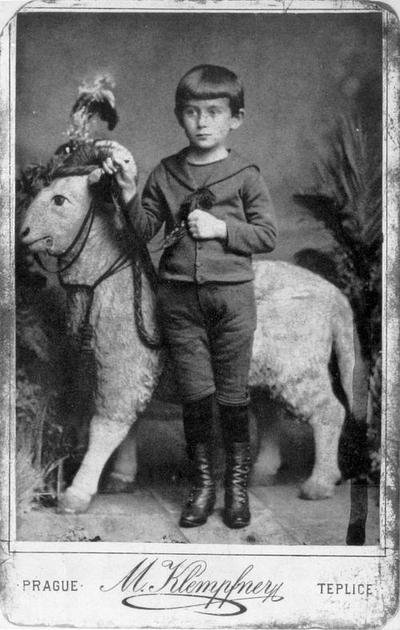

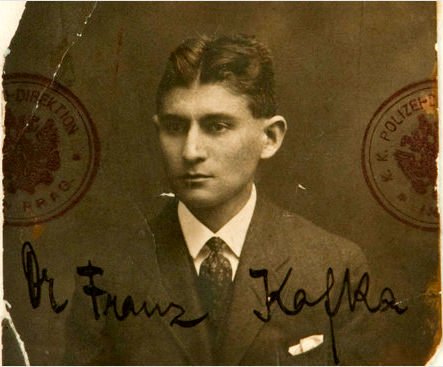

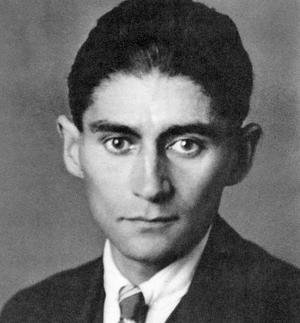

In his brief existence of forty years, let us remember that Franz Kafka was born in Prague in 1883 and died in the same city in 1924, this writer left us a great narrative work of incalculable literary value, such as The Process, The Castle, or the brilliant and famous Metamorphosis; but he also left us a considerable amount of personal papers, correspondence, notes and diaries, which come to speak to us of a tormented, dark existence, rich in interior experience and emotions.

One of the most prelevant themes in his work is the difficult relationship he had with his girlfriend Felice Bauer and the relationship with a despotic father. It was known that he never stopped despising his son and until 1922 he oppressed him. From this terrible confrontation "and from his tenacious meditations on the "mysterious mercies" and the unlimited demands of Patria Potestad, Kafka himself declared that all his work, in particular his famous Letter to the Father, came from him". which, as we all know, by obvious considerations, was never published in life.

Before beginning the analysis of this text, we must remember that this letter, of a rare length, never reached the hands of the father, Hermann Kafka. Its beginning immediately gives us the idea of what feelings the author has for his father and what the terms and tone will be in which he will address him:

Dear father:

Not long ago you asked me why I say I'm afraid of you. As usual, I did not know what to answer you; partly precisely because of the fear I have of you; partly because the explanation of that fear involves too many details to be able to expound it with medium consistency.

In these first lines we see what is the predominant feeling in Kafka's heart, the deterioration of his relationships with his father and how he uses the card to let off steam. In this letter he talks about a fear of his father and how that fear limits him to relate openly with the paternal figure. In this missive, Franz Kafka repeatedly brings passages from the past where the traumatic way in which he related to the father is evidenced:

In a direct way, I only remember one incident in the early years. You may also remember it. One night, I kept crying for water; not because I was thirsty, but partly because I was uncomfortable and partly because I was distracted. Seeing that a few shouts of threat had no effect, you took me out of bed, took me to the terrace, and left me alone in my nightgown in front of the closed door... No doubt I was obedient later, but I was damaged inside.

Like this passage, in the letter we can find some moments in which the writer claims from his father gestures or rude behaviors of the past and that marked him negatively. From some of the events narrated in some of his biographies, we know that Kafka felt like a foreigner within his own family. In his diaries we find reference to loneliness, persecution and even helplessness.

In the same way, we will find the exaltation of the maternal figure, but also the judgement of the latter for her passive attitude towards the husband, her unconditional love, her tireless search to keep father and son united. He presumes the closeness he has with the mother and how he can feel her, finally, closer:

It is true that my mother showed herself to me in boundless kindness, but all this was, for me, related to you, and was therefore not a good relationship.

In fact, he presumes how in personality and dealings, he can be more like his mother; how the motherly line can predominate in his character:

Compare us, you and me; I, to put it very simply, am a Löwy... You are, on the contrary, a true Kafka, by your robustness, health, appetite, humour, ease of speech, self-satisfaction, worldliness, tenacity, presence of spirit, knowledge of people, a certain generosity.

Löwy is the mother's surname. Franz confesses to his father that he does not feel that he is a Kafka, that the characteristics that people with this surname possess, he does not have them. In fact, he lists the qualities of the father, which he apparently does not possess. In that sense, we glimpse a deification of the father, the figure above all, but also accuses him of inhuman:

You can only treat a child as you have done to yourself, with harshness, shouting and anger, and in your case, this treatment also seemed very appropriate, because you wanted me to come out a strong and courageous boy.

Many parents may believe that a strict education, based on rigidity, rudeness, achieves more than one made on the basis of understanding, flexibility and condescension. In the case of Franz Kafka, he intuits that his father is reproducing the education he had; he even lets us glimpse a kind of justification for his behavior, saying what were the aspirations that the father had for him and that, apparently, it is not enough.

And in the face of a rigid and demanding type of education, people usually try to seek support from their other relatives, make them accomplices or allies. In the case of Kafka is no exception, it is known that for the writer Ottla was his favorite sister, but also his mother comes to protect him from the excesses of the father:

My mother limited herself to protecting me from you in secret; in secret, she gave me something, she allowed me something; then I was again before you the creature affected by photophobia, false, conscious of its guilt, to which, due to its nullity, I could only reach by tortuous paths those things to which I thought I was entitled.

Another of the themes that Franz Kafka addresses in this missive is that of his literary vocation. Let's remember that his father paid for a good education in one of the German schools in Prague and that, later, Franz Kafka, after finishing his baccalaureate, was forced to study law, a career he never felt interested in, and obtained his doctorate in law in 1906. Those university years left him time to cultivate his philosophical and literary hobbies, which were his true passion:

With your aversion you attacked in a more correct way my writing activity and all those things, unknown to you, that were related to it. In that activity, in fact, I had gained some independence from you.... In a way I felt safe writing, I could breathe.... My vanity, my pride suffered, it is true, when you received the appearance of my books with a phrase that became famous among us: "Put it on the bedside table..... My writings were about you; in them I exposed the complaints that I could not formulate directly, leaning on your chest.

It must be pointed out that the perspective in which Kafka contemplates his life and in which the father is an enemy, an authoritarian being who attacks and who with his excess of education comes to go against his personality, is not new. Many writers have already approached this subject in a certain way, not only in the epistolary genre, but also in diaries, narrative and poetic texts. What makes these texts different from the others is the way in which the author assumed almost cosmically the struggle and disagreements, which attracted and repelled, with the father. In the previous passage, we observed the little importance that the father gave to the texts written by his son and how he assumed the literature, Kafka, as an escape to all the paternal-affilial conflict that he lived.

This letter, written by Kafka when he was finishing the most important part of his literary career and at the age of 36, never reached his father's hands. When he sends it to the mother to be passed on to the father, she does not and returns it to him. Until this last moment, we see how the mother acts as an intermediary between father-son relationships.

Finally, taking the time to write a letter to someone else, whether it's apologizing, making a complaint, showing a feeling, or simply greeting, is a purely human gesture that seeks communication with another to whom we wish to express or transmit our words. Normally this type of text is used when people are distant, not only physically but sentimentally, as we can appreciate in the case of father and son. When we read a text like this, we must immediately think not only of the degree of disaffection between Franz Kafka and his father, but also of the fear, that fear that he exposes at the beginning of the letter, which did not let him personally tell him all the claims that are exposed in this text.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES

Kafka, Franz. Carta al padre. Editorial Lumen: Barcelona- España.

https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/k/kafka.htm

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franz_Kafka

In this letter, he says that he is like a prisoner who intends to go away, which might be achievable, one could add by writing, that is, by ceasing want to be the equal of the father on the same ground as him, but at the same time, he has the project to turn the prison into a castle for his use, this project of transformation from prison to castle being his desire to marry, to succeed like his father the project of this greatest act, but it is not possible, because he can not be there in close relation with his father, on his most personal domain! If he really plans to escape, he can not undertake the transformation of the prison into a castle, and if he really wants to undertake this transformation, he can not escape, but Franz Kafka will never choose, he will always want two things contradictory.

That's right, my dear friend! One of Kafka's most genuine feelings was his contradiction: on the one hand his rejection of the father and on the other his praise. In the same letter we observe how at times he speaks of the greatness and perfection of the father, and how he can never be like the father. That confused, imprecise attitude, perhaps normal in any child with respect to the father, is the one that many have used to make psychoanalytic studies from the figure of Oedipus. Thank you for commenting, @kouba01

Hi #adsactly sir...There should be an awakening among the people, that through their awakening, their own artistic culture, consciousness, and human consciousness can be further developed. The creator of this great universe and nature, he did not create human civilization but. People are the artisans of this civilization. Humans have destroyed the civilization over the ages, have developed the new civilization. But some great dignitaries, by the hands of some wise and creative people, the civilization has been restored.

Maintain the nature of the big responsibility of civilized people. The nature that gives us almost all of our livelihood, we can preserve it properly, along with its tradition of civilization, the tradition of civilization that is properly preserved in the spirit of humanity. The tradition of civilization evolved from history and tradition. Therefore, saving the heritage is a great responsibility for the civilized people to save tradition...

Out of all of the terrible yet relatable things that happened to Kafka, the letter to his father struck me the most. I know very well what it's like to have an overbearing, cold, distant, psychologically and physically abusive father and I know what it's like to try and look for forgiveness and connection. And yet I can't imagine the unending whirlpool of anxiety and fear that the days after he gave the letter to his mother were and how defeating it must have felt to get the letter back. All the fear and anxiety and even worse, the hopes and dreams of reconnection and understanding all gone because of his mothers cowardice. His innermost thoughts and feelings, rejected, deemed unsatisfactory. I should read his books again.

Very well said, @shihabieee. The feelings before and after that letter must have been a mixture of many things: anxiety, fear, pain, pride. I believe that although I did the exercise of writing everything I felt for the father, the evil was already done; the resentment was concealed in Kafka's heart. It's always good to go back to good books and good authors. Greetings

I've read "The Trial" three times, and theres something dark and bitter about it while at the same time it's intriguing and fulfilling. Later on i dived into his letter to his father which was extremely illuminating, the connections between his father and the court was blatantly obvious, but not in a way that made it feel exagerated or exhausted. It's amazing how important ones childhood is, if i remember correctly Kafka himself said that his entire authorship was about his father.

That's right, @itexpertshariful, and it's good that you mentioned The Process, maybe it's the story that comes closest to the idea of the Kafkaesque, because that's where an ordinary man finds himself trapped in a guilt that seeks his punishment, following an inverse logic to the idea of justice. There the contradiction, the absurd, elements so present in his work, everything in Kafka's was a relationship, a bond. Thank you for your comment

If he was my friend, I would give consolation to Kafka saying that it was important that he wrote that letter, because the healing is in the writing process. But even if his father read it, he wouldn't ask for forgiveness anyhow... I know from experience that the only way you can deal with a violent, condescending, horrifying parent is dark humour. You must give up all hope on "reaching" to that person. But isn't there also a wisdom and humility in accepting the " impossibility" of communicating with certain type of cruel and sick people?

According to what you say, @robiul985340. I believe that writing about certain things can be an exercise that helps bring out negative and repressed feelings! And understand that our words may not be able to change the other. There are dark beings who will never see the light! Thank you for commenting.

It's still amazing that there are fathers out there that still act in this way... its bitterly disappointing that they themselves never had the nerve or courage to rise up and say "No, I won't continue the cycle - it will break with me,"

Yes, Kafka's father is just one example of the many parents who, more than physical abuse, commit worse abuse, the one that leaves no traces: psychological abuse!

As a follower of @followforupvotes this post has been randomly selected and upvoted! Enjoy your upvote and have a great day!

Very interesting and complete this analysis that you do, my dear @nancybriti. Actually the father-son relationship determines the personality of many. In the case of Kafka it is unfortunate that he had to live the bad experience of having an abusive father. He never imagined that the psychological damage that he caused to his son, even in the appearance he looks sad, minimal, unprotected. However, it was a big letter. Excellent publication! Thanks for sharing, @adsactamente

That's ... so tragic. To think that this is just one of the millions that so happened to have written books AND got them noticed after his death. The countless people who have experienced the same, or even worse, without a story to tell, or had one but no one noticed ...

That's right. Thanks for commenting!

Hmmmm!.. Father and son relationship was not cordial, this has a lasting mental and emotional damage to the child's growth. He couldn't still let his father know about his (son) feelings towards him, rather he resorted to writing him a latter to express himself.

A sad story.